Confessions Of An Accidental Wood AnatomistCareers In BotanyAlex C. Wiedenhoeft, Botanist, Center for Wood Anatomy Research, Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, USDA

These are the confessions of an accidental wood anatomist. It seems strange to me now to reflect and see my path as accidental (it would be better to say serendipitous), but my trip to wood anatomy was nothing if not filled with chance. Not only am I an accidental wood anatomist, I cannot even claim that I always wanted to be a botanist, though it seemed clear from an early age that I would go into some branch of biology. My botanical studies began when I was home during winter break between the first and second semester of my freshman year of college. I woke up one morning, lurched upright in bed and said aloud, “I’m going to be a botanist.” Later that fateful morning, I registered for the Honors section of my first botany course, Professor Ray Evert’s famed General Botany, in the Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin-Madison. A few weeks later, I attended my first lecture and I knew that I had made the right choice; something about botany, and especially plant structure, was compelling to me. My employment while a student served to solidify my interest in plant structure.

As a botanist in the famed CWAR, home of the world’s largest research wood collection, I have had the privilege to work in a variety of wood anatomical fields. Contrary to popular belief (if there is any such thing as a popular belief about wood anatomy), wood anatomy is an exciting, dynamic, and relevant field of research, and there is no better place to ply the trade than at the nation’s (and one of the world’s) leading wood research laboratory, the FPL. The three main emphases of my work have been 1) traditional wood anatomy and wood identification research, 2) the biology of wood products, and 3) forensic wood anatomy. My published work in traditional wood anatomy and wood identification has been mostly collaborative, and emphasized the anatomical nomenclature and identification of pines (Pinus), described the wood anatomy of several new species of plants collected by Professor Berry and his students, and made inferences about paleoclimate from wood and tree rings. This area of my professional life is the most traditionally academic, even to the point of being staid, at least to outside eyes. Being inside the projects, digging in on an anatomical question, or being the first human ever to look at the microscopic structure of a new species; these are joys that you can only experience sitting at your microscope, and can be hard to convey in just a few words. I have found delight and inspiration in the wood of plants from all around the world, though it is good to note that I am not a field botanist by any stretch. I generally characterize myself, only half in jest, as a glorified microscope attachment. For me, this does not have a pejorative connotation. My happiest working hours are typically seated at my Leica, mumbling, cursing, oohing, and ahhing over something I am researching, whether it be a new species or a piece of plywood. To understand wood as a material in human contexts, we should understand wood as a material in its original botanical context. This is my area of greatest interest in wood science and wood technology, and I have been able, at least in part, to bridge the gap between a botanical view of the tree as an organism and the view of engineers and chemists with whom I work. My published works have generally emphasized the relevance of wood structure to wood decay, adhesives interactions, and the durability of wood finishes. When I am asked to speak at wood products or wood science conferences, it is generally on the topic of the interplay between the biology of the tree and wood properties. I recently participated in a training workshop for Major League Baseball approved baseball bat manufacturers. My role was to demonstrate the botanical and wood anatomical bases for the differences between various species employed in the manufacture of bats, and to apply this knowledge to the spectacular bat failures in the 2008 season.

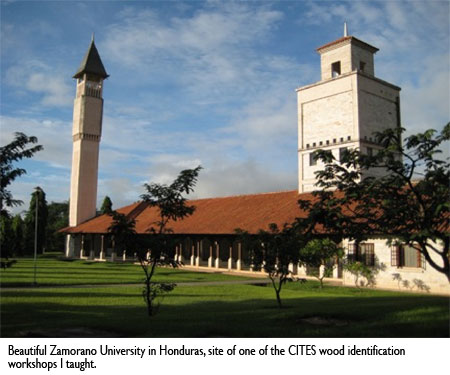

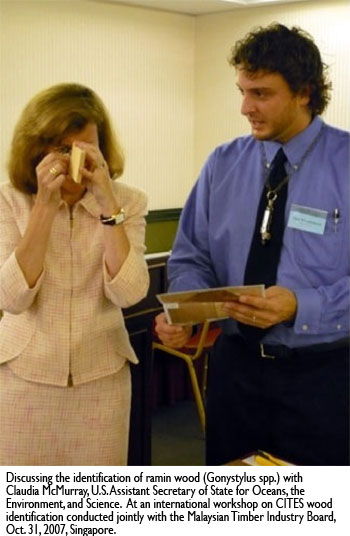

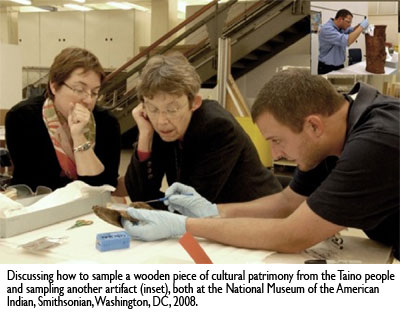

One of the most surprising aspects of forensic wood anatomy is how routine the science tends to be. In most cases, forensic evidence is quite straightforward to identify. The same can often be said of more exotic non-criminal wood identifications. A wood specimen from a beautiful statue of Osiris from 540 B.C. for a museum: 10 minutes of work. A wood specimen taken from the skull of a saber-toothed tiger from the La Brea tarpits: 10 minutes of work. Specimens from Blackbeard’s ship (yes, the pirate): a few minutes each. Though the context of such specimens is interesting, the specimens themselves rarely pose much of a botanical mystery. The converse is also often true; it has been my experience that a specimen from a mundane context (a piece of driftwood, a root found in a sewer pipe) can be a much greater scientific challenge. One facet of forensic wood anatomy that has continued to provide me a scientific and didactic challenge has been developing wood identification tools for non-botanists to combat illegal trade in tropical timbers and to prevent illegal logging. In 2002, Dr. Regis Miller, Marie-Josie Ribeyron, and I published the CITES guide for tropical timber identification. The guide was published originally in English, French, and Spanish. It has since been translated into Polish and Chinese, and I have been told that an Arabic version is forthcoming. Using the guide as a textbook, I have traveled to Nicaragua, Honduras, and Singapore, as well as within the US, to teach workshops on the identification of CITES-listed tropical woods. I have taken a brief rest from writing a bilingual guide to the commercial timbers of Central America to write this account for Careers in Botany. It has been a thrill and a joy to take basic plant anatomy, a low-profile and often low-tech area of inquiry, and make it accessible to law enforcement officers around the world, all while playing a role in protecting endangered trees. With the recent passage of the Lacey Act amendment in 2008, there is a greater need than ever for botanical expertise in our industries, universities, and government agencies. For anyone considering an academic or professional career in botany, I have two pieces of advice to share. The first comes by way of Professor Ray Evert who, when he took a group of newly admitted graduate students through his lab, told us “Make your vocation your avocation” - love what you do. The second is a nugget of perspective from my own career; apply what is traditionally seen as strictly pedantic knowledge (like wood anatomy) to real world problems, and you will find that the world can be as excited by and interested in your field as you are. Good luck, work hard, and have fun!

|

I held three jobs concurrently as an undergraduate [a landscaper, a student hourly in the Genetics department in Patrick Masson’s lab, and a student at the Forest Products Laboratory (FPL), Center for Wood Anatomy Research (CWAR)], and the latter two influenced my development as a botanist. Patrick Masson’s lab was working on root gravitropism in Arabidopsis. I washed dishes, performed cookbook molecular biology as directed by graduate students and postdocs, and conducted controlled crosses by emasculating and pollinating flowers. I learned many interesting things in that lab, and developed an interest in tropisms that mostly extends to fungi for me now. Of particular note, though, was a telling conversation I had with a colleague. She said to me, shaking her head, “I can’t believe you can spend hours and hours looking through a microscope” I smiled and said, “I can’t believe you can spend a career working on something you’ll never see.” It was a friendly, glib retort but it did get at the core of something for me; I found plant anatomy, and specifically my wood anatomical work at the CWAR, more satisfying than molecular biology. There is something about cutting apart a plant, seeing its structure, and trying to understand the role that structure plays in its physiology that I find almost addictive.

I held three jobs concurrently as an undergraduate [a landscaper, a student hourly in the Genetics department in Patrick Masson’s lab, and a student at the Forest Products Laboratory (FPL), Center for Wood Anatomy Research (CWAR)], and the latter two influenced my development as a botanist. Patrick Masson’s lab was working on root gravitropism in Arabidopsis. I washed dishes, performed cookbook molecular biology as directed by graduate students and postdocs, and conducted controlled crosses by emasculating and pollinating flowers. I learned many interesting things in that lab, and developed an interest in tropisms that mostly extends to fungi for me now. Of particular note, though, was a telling conversation I had with a colleague. She said to me, shaking her head, “I can’t believe you can spend hours and hours looking through a microscope” I smiled and said, “I can’t believe you can spend a career working on something you’ll never see.” It was a friendly, glib retort but it did get at the core of something for me; I found plant anatomy, and specifically my wood anatomical work at the CWAR, more satisfying than molecular biology. There is something about cutting apart a plant, seeing its structure, and trying to understand the role that structure plays in its physiology that I find almost addictive. I had the good fortune to begin my career, though I didn’t know it as such at the time, when I was 18 years old. In my job at the CWAR I first worked for Dr. Harry Alden. I progressed quickly from washing dishes to database work to making freehand sections of Abies for a wood identification project, and then to a larger study of the wood identification of two commercial species of western yellow pine. I learned to make permanent, research-quality slides of wood using a sliding microtome, and Dr. Alden first allowed and later encouraged me to spend a few hours each week learning about wood identification. This was a heady time for me at the CWAR, and Dr. Alden was indulgent regarding my many questions about wood anatomy and wood identification. It is fair to say that Dr. Alden gave me my first job as a botanist, and that he began the core of the training that would come to define my area of professional expertise. Dr. Alden left the CWAR around the time I completed my B.S. in Botany; I continued my training under the tutelage of the world-renowned systematic wood anatomist, Dr. Regis B. Miller. I worked for and with Dr. Miller until his retirement in January 2005. Dr. Miller and FPL supported my desire to pursue a graduate education, and, studying under Professor Paul Berry, I earned my M.S. (ecophysiological wood anatomy of seasonally flooded trees) and recently my Ph.D (the comparative wood anatomy of Croton (Euphorbiaceae) in the context of molecular phylogenetics) in Botany from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Academically speaking, I am somewhat inbred, with all three degrees from the same Department of the same institution. Though generally frowned upon, in my case it was desirable thanks to the strength of the UW-Madison Botany Department, and because a running theme throughout my education was the CWAR itself.

I had the good fortune to begin my career, though I didn’t know it as such at the time, when I was 18 years old. In my job at the CWAR I first worked for Dr. Harry Alden. I progressed quickly from washing dishes to database work to making freehand sections of Abies for a wood identification project, and then to a larger study of the wood identification of two commercial species of western yellow pine. I learned to make permanent, research-quality slides of wood using a sliding microtome, and Dr. Alden first allowed and later encouraged me to spend a few hours each week learning about wood identification. This was a heady time for me at the CWAR, and Dr. Alden was indulgent regarding my many questions about wood anatomy and wood identification. It is fair to say that Dr. Alden gave me my first job as a botanist, and that he began the core of the training that would come to define my area of professional expertise. Dr. Alden left the CWAR around the time I completed my B.S. in Botany; I continued my training under the tutelage of the world-renowned systematic wood anatomist, Dr. Regis B. Miller. I worked for and with Dr. Miller until his retirement in January 2005. Dr. Miller and FPL supported my desire to pursue a graduate education, and, studying under Professor Paul Berry, I earned my M.S. (ecophysiological wood anatomy of seasonally flooded trees) and recently my Ph.D (the comparative wood anatomy of Croton (Euphorbiaceae) in the context of molecular phylogenetics) in Botany from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Academically speaking, I am somewhat inbred, with all three degrees from the same Department of the same institution. Though generally frowned upon, in my case it was desirable thanks to the strength of the UW-Madison Botany Department, and because a running theme throughout my education was the CWAR itself.

Not all my interactions with wooden sporting implements have been positive; I identified the wood from a pool cue used as a murder weapon. In the course of my forensic botany work, I have analyzed wood evidence from: plane crashes, arson, an attempted car bombing, woody material appearing in food products, evidence from a variety of murders and assaults including a murder case for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and material from numerous other cases. One of my favorite cases dealt with the wood anatomy and identification of sauerkraut, and involved wood anatomy, general plant anatomy, plant development, industrial practices, and agronomic concerns. Based on my experience working with various crime labs and my dismay at the generally poor state of wood evidence submitted to me, I authored a prescriptive paper regarding the proper collection, documentation, and storage of wood evidence for Evidence Technology Magazine.

Not all my interactions with wooden sporting implements have been positive; I identified the wood from a pool cue used as a murder weapon. In the course of my forensic botany work, I have analyzed wood evidence from: plane crashes, arson, an attempted car bombing, woody material appearing in food products, evidence from a variety of murders and assaults including a murder case for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and material from numerous other cases. One of my favorite cases dealt with the wood anatomy and identification of sauerkraut, and involved wood anatomy, general plant anatomy, plant development, industrial practices, and agronomic concerns. Based on my experience working with various crime labs and my dismay at the generally poor state of wood evidence submitted to me, I authored a prescriptive paper regarding the proper collection, documentation, and storage of wood evidence for Evidence Technology Magazine.