My journey to botany with a specialty in plant systematics dates back to the early eighties in China and has continued in the US since 1989. It’s a journey of adventure, excitement, and hard work that would not have been possible without the help and support of my colleagues, friends, and family.

It began in China…

It is hard to believe that with a childhood dream of becoming an astronaut, I end up as a botanist with a passion. The curiosity that developed from listening to legends and tales, and from pondering the moon-lit night sky planted a strong desire in my heart when I was little to seek answers to the many questions I have about the great universe. Unexpectedly, this aspiration was overtaken by a growing interest in biology after I entered college.

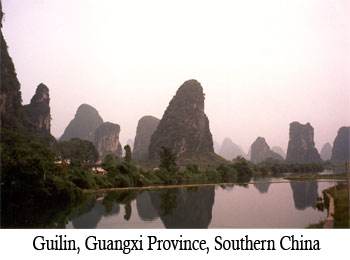

Born in a small town in southern China and growing up with the Cultural Revolution and other political movements in the seventies, I had only a total of nine years of education from 1st grade through high school where the word biology was never seen and replaced by field labor in the rice and vegetable fields. Fortunately, the year I graduated from high school, the Cultural Revolution ended and higher education in universities was reestablished. High-school graduates could attend colleges directly on a competitive basis without having to be sent to the countryside for a second education.

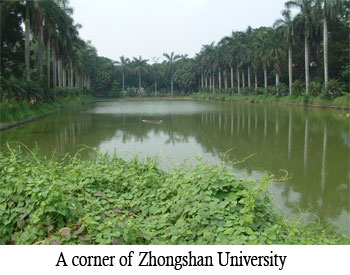

I felt so lucky to have been part of this historical time of change. In my application to colleges, I put all the natural sciences I knew as the major (e.g., mathematics, chemistry, and physics). However, I was admitted by Zhongshan University (Zhongda) to study plant genetics in the biology department. Fortunately, I was still quite young (15 years old), and didn’t know much about the world anyway, so it wasn’t hard for me to take on something completely unknown.

The biology department opened a whole new world for me. For the four years, I did almost nothing except study. The plant genetics track of the biological curriculum at Zhongda had a long list of required biological classes (there were no electives at that time), besides the general common courses such as one year of advanced mathematics, chemistry, physics, political economics, and English. Some of the biological courses included one year of general botany (morphology and anatomy), and one year of plant systematics, one year of plant physiology, one year of biochemistry, one semester of cell biology, general genetics, medical genetics, plant genetic breeding, general zoology, animal physiology, microbiology, biotechnology, as well as biological English, etc. In addition, a senior thesis based on a research project conducted in the last semester was required for graduation. Among all the courses, the plant systematics course attracted my greatest interest.

Growing up in a mountainous subtropical area with green plants all year around, I had always puzzled about what they were. The plant systematics course taught me how to identify plants, how they are similar and different and how they are classified. I was so happy when I could name the plants I saw on campus, in the field, in a park, or on the street, or could tell what families they belonged to and why. I was fascinated by the great wonder of structural diversity in flower, fruit, and leaves. Most students in my class did not like the course due to overwhelming terminology and family characters. Somehow, I was an exception. That was the beginning of my journey into Botany, and particularly to plant systematics (the science of plant biodiversity, in short). The four years of college study laid the foundation for my future career in botany I enjoy so far. The college life left me with a wonderful memory and more desire for seeking new knowledge in plant biology.

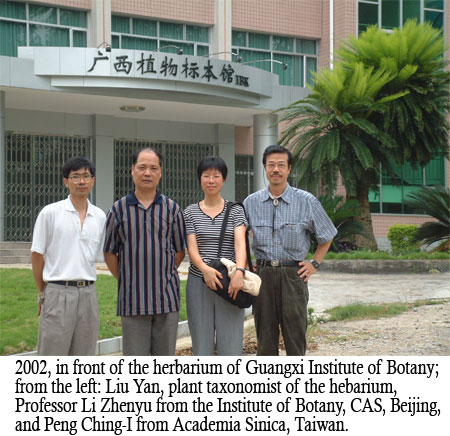

During the early 80s, there was a great need for young people in research institutions and universities in China. Graduated students were assigned jobs by the government according to the need. After graduation, I was assigned a position in the department of taxonomy, Institute of Botany, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Beijing. My mentor was Prof. Tang, Yancheng. This taxonomic department (now the State Key Lab of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany) had been the largest and strongest among all universities and CAS botanical institutes in different cities of China. It had the largest herbarium in Asia and has the best resources of facilities and faculty compared to other institutions. Prof. Tang (now 81) had been well-known in the department and in China due to his broad knowledge in methodology of systematics, up-to-date information on literature, unusual capability of critical evaluation of peer work, and also his humble and modest lifestyle.

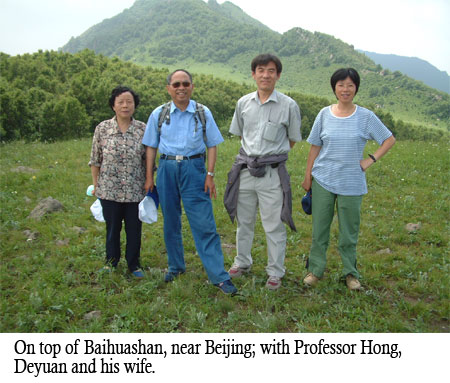

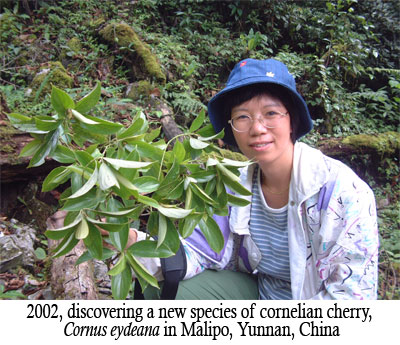

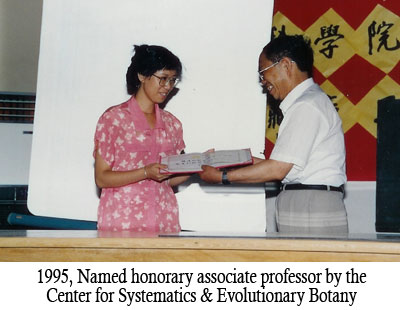

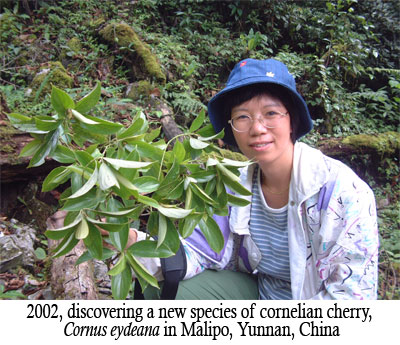

I worked closely with Prof. Tang and the cytology lab directed by Prof Hong, Deyuan (now a CAS member) as well as the morphology & development lab directed by Prof. Anmin Lu for seven years before I left for the United States. During those years, Prof. Hong, Prof. Lu, and especially Prof. Tang set for me good examples of traditional Chinese scholars and modern plant systematists. Their ideas moved along with the advancements in systematics of the western countries. My current research interest in the dogwood family (Cornaceae) can be traced back to the early practicing of taxonomic research by the group under the guidance of Prof. Tang. The dogwood genus was chosen as the target group because of the considerable debates among taxonomists in different countries on the delimitation and classification within the dogwood genus Cornus L. s. l.. The in-depth literature research, broad study of specimens from the world, and investigation of micromorphology of the group, prepared me with some fundamental skills for a career in plant systematics.

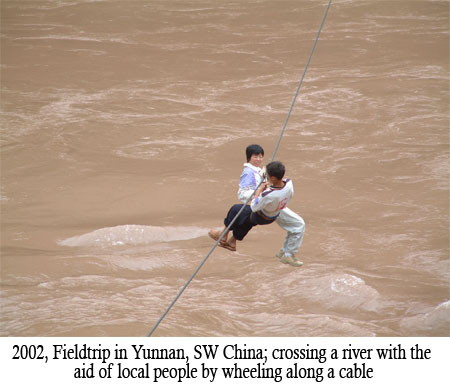

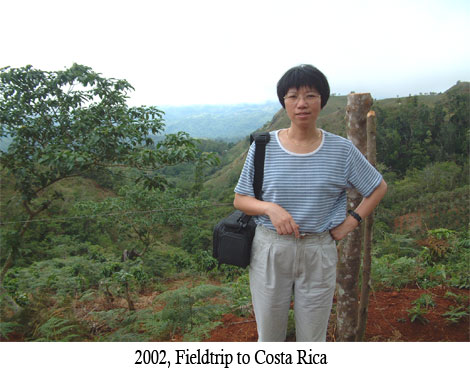

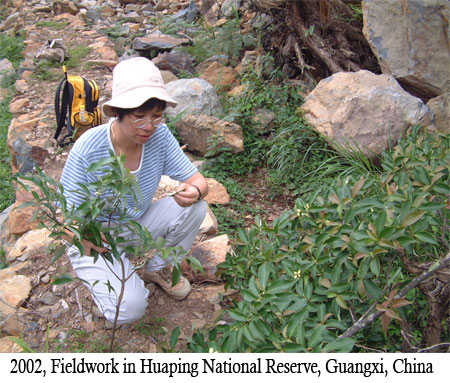

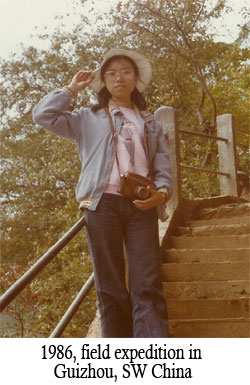

The value of systematics (often regarded as a synonym of Taxonomy in China) was often underrated in the scientific society in China. It was not something considered “high” in the biological community, at least in China at that time, because it was an old discipline and most taxonomists were working on Flora of China -descriptive and somewhat subjective, e.g., changing taxa names, and classification schemes, etc. But taxonomy had its exceptional rewards, such as the exciting moments of discovery of new characters and species that resulted from fieldwork and careful examination of herbarium specimens. Aside from this, a taxonomist had the opportunity of travel to different places to study variation of plants in the mountains and herbaria located in other cities. Such opportunities allowed me to see and experience the world of people and nature. Modern plant systematics does not only involve naming, describing, and identifying plants, but also has a major goal of understanding pattern, history, and causes of plant variation, which requires careful comparative analyses of data gathered from laboratory, field, and literature. A combination of lab work and field work in my job is still the best thing I have liked as a plant systematist. To me, systematics is a discipline of adventure and discovery.

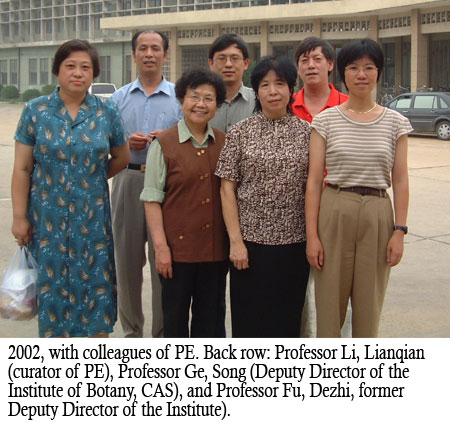

The seven years of work in the Institute of Botany was an important period on my journey to a career in botany, as well as to my life. I married my husband and had my first child. The colleagues and friends I made during those years became an important network in my later career. The botanical expeditions in southern and southwestern China in which I participated greatly enriched my experience in botany and benefited me throughout my entire journey in plant systematics. The field trips still live vividly in my memory and bring me laughter and pleasure whenever I talk or think about them. Whenever I go back for a visit, I always feel like I am coming home. I miss the Beijing Botanical Garden in which the institute is located, the many friends, and the Zoo of Beijing where the Institute was located.

Continued in the USA…

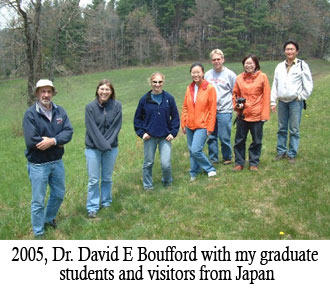

A turning point occurred in 1989, the year I had the opportunity to visit the United States and work with Dr. David Boufford at Harvard University Herbaria, and the late Dr. Richard Eyde, the American dogwoods expert, at the Smithsonian Institution. Coincidently, my husband, a plant ecologist in the same Institute, had an opportunity visiting the Edinburgh Botanical Garden the same year. After arranging for my 10-month old daughter to stay with my parents, I set off for America. I clearly remember how I felt when I first arrived in the US. I felt like Alice in a Wonderland when I walked out of the airport in San Francisco, bathed in the warm and sweet spring breezes under the blue sky and surrounded by fast-walking “foreigners” and cars… It was breathtaking to see the clean, wide streets and magnificent buildings in Washington DC, Boston, and Cambridge. I was extremely impressed by the fact that there was hot tap water all day long in all of the buildings and my shoes and nose stayed clean and dust free after a long day of walking outside. It felt like in a dream that could not be true!

Coming to the US was a challenge: I could not understand much English and most of the knowledge about plants I learned in China was, obviously, Chinese. Both Drs. Boufford and Eyde were great teachers to me in botany and English. While working hard to accomplish my work and improve my English, I also enjoyed the incredible museums at Smithsonian institutions, the Cherry Festival parade in Washington DC, and the most beautiful fall colors of New England.

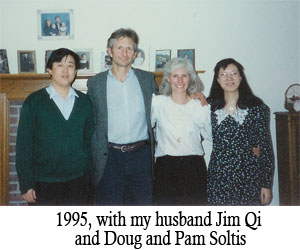

The inadequacy of knowledge and experimental skills in Botany I recognized in myself urged me to pursue advanced education in the United States. With the help and recommendation of Dr. Boufford and Dr. Eyde, I took the “painful” TOEFL and GRE exams, and was luckily accepted by Doug and Pam Soltis at Washington State University, who were running an active research program on modern plant systematics.

The five years at Washington University gave me the richest experience and the most important training for a career in modern plant systematics. Among other things, the preparation for preliminary exam, writing my first manuscript and grant proposal in English, presenting work at professional annual meetings, and the teaching experience benefited me the most in preparing for an academic career in plant molecular systematics.

In preparation of the preliminary exam, I spent a semester reading books and papers. The principle, methodology, their applications in case studies, and the theories and rationales behind the research work all came into light for me. This process, although somewhat stressful, lifted me to a different level of understanding the systematic discipline.

Writing the first manuscript in English took several rounds of back and forth changes between me and my advisor. I can image how much time Doug spent on the word-to-word correction on each draft and how frustrated he might have felt because even I grew sick of it. Writing my dissertation improvement grant entailed a similar process. These processes taught me a great deal of scientific writing and were exceptionally educational and beneficial in the long run, although they took more time and effort than usual (as for American students). Writing in English is still a big challenge to me today.

My first oral presentation at a professional meeting was another important step in overcoming my personal shortcomings. I had never stood in front of a group of people to speak before. The experience is still clearly imprinted in my mind. I failed completely at the first lab group rehearsal, mumbling broken English that no one could hear or understand. After gathering many helpful comments and suggestions from the lab group, I worked hard to think through what exact words I wanted to say. With countless practices, and numerous changes, I made a huge improvement in the second rehearsal and became ready for the meeting. However, standing in a room talking to critiquing strangers was nothing like the lab group rehearsal. My hands went cold sitting in the room waiting for my turn to talk. However, seeing Doug and Pam, and the entire lab group in the room gave me the courage to finish a smooth presentation. This experience surprised me, proving to me that I could speak in front of a group of people if I had to. It was an important discovery for me and I learned that courage, practice, and hard work could create wonders.

My first two years at WSU were supported by a curatorial assistantship, which did not require much English. The third year, however, my support was switched to TA for the introductory Biology course. This was the greatest challenge I had to face during my graduate study. Two obstacles faced me: one was speaking to a class and the other was the language difficulty. Most of my general biology knowledge was in Chinese: it needed to be translated into English and expressed in a way for non-biology major students to understand. Despite my anxiety, I knew that if I could learn how to teach in a classroom, it would help me one way or the other in the future. I also knew that it was not usual for foreign students to receive TA support. So I took this unusual opportunity to develop my ability to speak English and teaching and went forward. Although there were many difficulties and many hours of preparation for each lab in the first semester, it became easier with time. I came to enjoy it. The three years of teaching experience was essential to a future career as a professor. I am very grateful to have been given that challenge and opportunity which led to the discovery of my potential for teaching. I had never imagined myself as a teacher when I was in China, especially due to my shyness of public speaking.

Doug and Pam advised me that research productivity was the most important for the success of a Ph.D. student. So I used my weekends, holidays, and summer vacation to catch up the research that fell behind due to the teaching. My successful graduate study experience taught me to trust my advisor, follow instructions, set short- and long-term goals, work hard, keep up frequent communication with the advisor about experiment results, progress, and problems, and take every task positively, believing in an eventual reward from it, no matter what shape the reward might take.

With all the work, it did not mean that I did not have a life. I had some of my best experiences in Pullman after I came to the US. My daughter and my husband joined me in the second year of my study at WSU. Today, I miss the laughter and music in the lab while working, the many parties in the Soltis’ house for celebrating birthdays and achievements of students, the Chinese village of the university housing campus, the fun of camping and fishing by the Snake River, the fun of sledding on the hill in the winter, and the fireworks at the Sunnyset Park.

If getting a Ph.D. is like a chicken hatching from the egg, the post-doctorial study would be like growing feathers, and an academic position as a professor at a university would be like a hen ready to produce its next generation. My two years post-doctorial study at Ohio State University with Dr. Daniel Crawford and Andrea Wolfe was my time for growing feathers. Working on the buckeye genus (Aesculus) at the Buckeye state was peculiar. During those two years, I learned how to become a more independent and critical thinker, how to apply phylogeny to understand the history of plant distribution, and experienced different ways of running and organizing a research lab, and most importantly how to teach a course on plant diversity. This experience was eye-opening and important to my adventure into the plant systematic career as a professor at a university.

A Career as a professor in Plant systematics…

In the second year of my postdoc study at OSU, I had my second child. After five weeks of his birth, I interviewed for my first tenure-track assistant professor in plant molecular systematics position at Idaho State University and was offered the job. I was reminded by my advisor that a university professor is expected to know everything by students. A faculty position at a university usually has responsibilities in three main areas: teaching, research, and service.

The first year tended to be the most difficult for a new faculty member due to heavy workload of developing and teaching the courses, establishing a research lab, and recruiting graduate students. My position also included the responsibility of a curator of the herbarium at ISU. My teaching responsibilities included several courses for the three and a half years at ISU: Systematic Botany once a year, Molecular Systematics for one semester, General Botany for one semester, Economic Botany for one semester, and a senior seminar every semester. Although it wasn’t easy and required a lot of time to teach these courses in addition to starting a research program that would train MS and Ph.D. students (it usually meant no holidays, no weekends, and very little sleep), I actually enjoyed the work. I had the freedom to teach a course the way I wanted to, and I found that teaching itself was a different learning process. While teaching the students I taught myself in preparing the classes and seeking answers to students’ questions. I think an instructor should serve to facilitate the learning of students, not to act as an encyclopedia of facts. As it is not possible for any person to know everything or teach everything he knows in a course, it is very important to teach students the skills and methods of seeking new knowledge and finding answers to their questions. I believed I learned and enjoyed more than the students in teaching those courses. It was both wonderful and encouraging to see students learning and appreciating the teaching.

Research is an exciting aspect of a faculty position at the university. I had the freedom to pursue the scientific problems of my interest. However, obtaining grant money to support the research program was very competitive and difficult. Plant sysetmatics is a basic science discipline in life sciences. The funding sources are relatively limited and the grants are usually small. I managed to generate the most data with the least amount of expense, something I learned from my Ph.D. advisors Doug and Pam at WSU.

The three years at ISU were the early parts of my adventure into a career in Plant Systematics. I enriched my experience in teaching and learned the skills needed to manage an independent research program. When my husband’s job relocated him in the East, I moved to NCSU to continue my academic career in botany. NCSU is a wonderful place to foster such a career, as its campus is home to more than 100 plant biologists, with more in the Research Triangle area, and the natural environment boasts a great diversity of plants. The department of botany (now Plant Biology) is strong in research, teaching, and graduate training. I felt lucky to be part of the group.

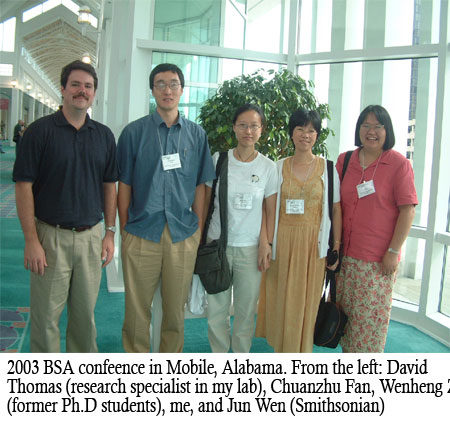

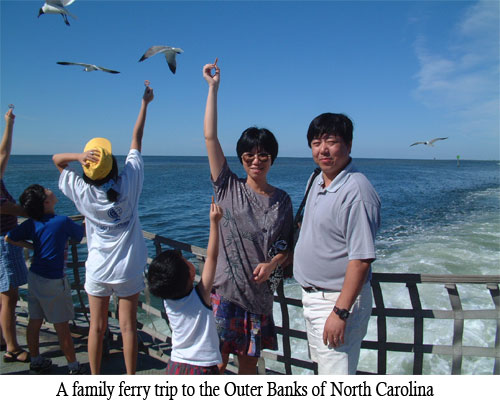

Several years have passed since I moved to NCSU. I have enjoyed both work and life here. With the support of the department, college, and university, I have managed to establish a good research program in plant molecular systematics and also have a wonderful group of people to work with. I teach the Systematic Botany course at both undergraduate and graduate level, as well as a lab and a seminar course for graduate students. I have made many domestic and international travels to collect plant materials and to attend professional conferences. It has been a great joy to see my graduate students finish their degree and move forward in the academic areas. The location of the university is also ideal because of its closeness to the southern Appalachian mountains as well as the Atlantic Ocean. Growing up in a mountainous region and as a botanist, I was probably born to like the mountains – green has always been my favorite color. The beach, however, was not a place I had ever seen before I came to the US—it had always been a wonderland to dream after. Living in the Raleigh Triangle area, with both mountains and beach within a few hours’ drive, has been wonderful.

Although a job as a professor is a demanding job due to many responsibilities (e.g., teaching in the classroom, maintaining an active research program, training undergraduate and graduate students, serving on committees of the department, and college, reviewing grant proposal and manuscripts, etc.), it permits a flexible working schedule. This flexibility is very important for someone like me who has to be a mother, a wife, and a professor at the same time, and whose spouse works full-time. Luckily, my husband helps with much of the housework, like taking care of bills and doing most of the grocery shopping, etc. so that I can have more time to do work. Life is usually hectic like with most American families. However, we are still able make time for family vacations, traveling to China, and community services, even if not as often as some of our friends. We are able to do things that are relaxing, such as watching movies in a theater, watching home videos, going out to parks for hiking, having friends over to sing karaoke, etc. It is not easy to balance work and family, but it is possible.

My journey to the botany career is a long one and probably harder than those of most other botanists, but I cherish every step of the journey that led me to this special career in plant biology.

Did I mention - this is all extremely fun???

That's all for now!

Botanical Society of America

www.botany.org

www.BotanyConference.org

www.PlantingScience.org

Mission: The Botanical Society of America exists to promote botany, the field of basic science dealing with the study and inquiry into the form, function, development, diversity, reproduction, evolution, and uses of plants and their interactions within the biosphere.