Simply put, Economic Botany is the interaction of people with plants. Economic botany is closely related to the field of ethnobotany - that word is based on two Greek roots: ethnos (race: people: cultural group) and botanikos (of herbs) and can mean the plant lore of a race or people as well as the study of that lore.

Simply put, Economic Botany is the interaction of people with plants. Economic botany is closely related to the field of ethnobotany - that word is based on two Greek roots: ethnos (race: people: cultural group) and botanikos (of herbs) and can mean the plant lore of a race or people as well as the study of that lore.

Economic botanists are scientists who study the interactions between humans and plants. That makes the field of Economic Botany as far flung and diverse as both the human and plant life on our planet. Economic botanists study human-plant interactions from a variety of different angles. These skilled researchers rely on a variety of disciplines including archeology, sociology, and ecology in addition to basic botany to help them explain these interactions and their effects on plants, society and our dynamic planet.

Knowledge Systems

Economic Botany sometimes focuses on the processes as well as the products involved in plant cultivation. Scientists ask questions about how knowledge of useful plants is acquired and transmitted between groups.

In the South American Andes, potatoes are the staple of many indigenous diets. Economic botanists are intrigued by the questions of who first ate this vegetable and why they thought it might be appetizing and nutritious in spite of the fact that the leaves and stems of the potato plant are poisonous.

What made these cultures think that there might be something worthwhile lying beneath the surface? How did they share their knowledge and with whom?

Uses of Plants

Uses of Plants

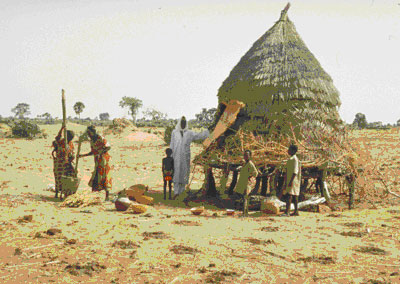

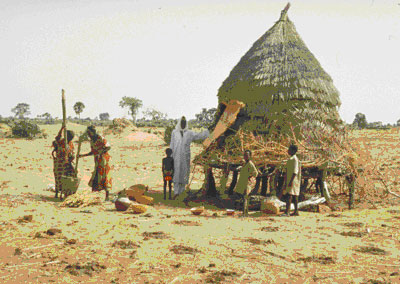

We can also study how plants are used. In the past this has meant lists of cultures and their preferred plant sources for food, clothing, shelter, medicine, ritual or aesthetics. Although there are roughly 250,000 species of plants divided into 460 families, we commonly use products from only 300 species in 20 of those families; just a tiny fraction of what’s available.

Often a single plant will fill more than one function. The coconut palm is an excellent example of botanical versatility. It is found in cultivation throughout the tropics where it is known by many names including pokok seribu guna or 'tree of a thousand uses' in Malay. All parts of the plant are used from the leaves that are woven into thatch roofs and mats to the delicious fruit and sap right down to the roots that are processed to treat everything from dysentery to bad breath.

Today, economic botanists continue cataloguing plant uses, but they also hope to discover new ones by screening for medicines such as anti-cancer agents or experimenting with ways to improve current cultivation and make it more sustainable or efficient.

Ecology, Evolution and Systematics

Studies of the evolution of cultivated plants include the processes of domestication and the relationship between natural and human selection of specific plant traits. Knowledge of botany is essential to understanding how domestication may have changed a plant species over time. In addition, ethnobotanists look for help from such disciplines as history, archeology and even linguistics to shed light on this process.

Take maize as an example. Botanically speaking, physical evidence, including DNA and similar morphology of stems and grains has shown that maize is related to wild grasses in Central America and Mexico. This agrees with what history and archeology tell us about how this crop was first cultivated there as early as 7000 years ago. The name also gives clues to the crop’s movement across cultures. Maize is the Spanish version of an Arawak word ma-hiz. The Spanish first encountered this grain in the Caribbean Islands and then introduced it to Europe; starting its eventual spread around the globe.

Landscapes and Global Trends

Landscapes and Global Trends

The impacts of human activity on the landscape and biological diversity are also of increasing concern to ethnobotanists. The effects of human presence can be seen in every ecosystem they inhabit.

Altering the landscape is not something that only developed agricultural societies do. Environments that might at first appear untouched and empty may in fact be carefully managed by their human inhabitants. Prairie and woodland fires were intentionally set by North American tribes using those areas for hunting and cultivation. These methods were practiced long before the arrival of European settlers who started felling trees and tilling fields in areas that seemed, to them, pristine and unclaimed.

While human activities are sometimes benign or even beneficial they can also create a burden on the landscape when key systems are disrupted by resource consumption or the removal of key species by overharvesting. Examples of negative cycles where overconsumption of natural resources has led to even worse depletion and decreasing diversity are unfortunately common. Truffles, a European fungus highly prized as a seasoning, are becoming increasingly scarce due to over-harvesting in the wild. The market value of truffles keeps rises as they get harder and harder to find which makes the truffle hunters work harder to find the few available ones. This leaves even fewer fungi to reproduce and supply the next year’s harvest.

While human activities are sometimes benign or even beneficial they can also create a burden on the landscape when key systems are disrupted by resource consumption or the removal of key species by overharvesting. Examples of negative cycles where overconsumption of natural resources has led to even worse depletion and decreasing diversity are unfortunately common. Truffles, a European fungus highly prized as a seasoning, are becoming increasingly scarce due to over-harvesting in the wild. The market value of truffles keeps rises as they get harder and harder to find which makes the truffle hunters work harder to find the few available ones. This leaves even fewer fungi to reproduce and supply the next year’s harvest.

As you can see, the simple definition of Economic Botany barely scratches the surface of these scientists’ accomplishments. They not only work among all the people and plant groups on Earth today, they also look back to past civilizations and forward to future discoveries and uses for as yet uncultivated or undiscovered species of plants.

Now that you can see what it’s like to be an economic botanist, try these exercises with other common crop plants. You’ll be surprised by how much you can easily discover about things we often take for granted like bread, rubber tires or cotton cloth.

Now that you can see what it’s like to be an economic botanist, try these exercises with other common crop plants. You’ll be surprised by how much you can easily discover about things we often take for granted like bread, rubber tires or cotton cloth.

Knowledge Systems

Where was rubber first used?

What was it used for?

When were the first rubber tires invented?

Uses of Plants

What other plants have multiple uses?

Which would you consider the most useful?

Ecology, Evolution and the Environment

Consider the Botany of wheat. How does it differ from other grasses?

What about the history of coffee can help us understand it's importance today.

Consider the name chocolate. What does it tell us about the origins of the plant Theobroma cacao?

Landscapes and Global Trends

How will the pressures of increasing populations and the need for more and more natural resources affect the landscape?

Can there be a balance between modern humanity’s needs and available natural resources that will prove sustainable for future generations?

Simply put, Economic Botany is the interaction of people with plants. Economic botany is closely related to the field of ethnobotany - that word is based on two Greek roots: ethnos (race: people: cultural group) and botanikos (of herbs) and can mean the plant lore of a race or people as well as the study of that lore.

Simply put, Economic Botany is the interaction of people with plants. Economic botany is closely related to the field of ethnobotany - that word is based on two Greek roots: ethnos (race: people: cultural group) and botanikos (of herbs) and can mean the plant lore of a race or people as well as the study of that lore.

Uses of Plants

Uses of Plants

Landscapes and Global Trends

Landscapes and Global Trends  While human activities are sometimes benign or even beneficial they can also create a burden on the landscape when key systems are disrupted by resource consumption or the removal of key species by overharvesting. Examples of negative cycles where overconsumption of natural resources has led to even worse depletion and decreasing diversity are unfortunately common. Truffles, a European fungus highly prized as a seasoning, are becoming increasingly scarce due to over-harvesting in the wild. The market value of truffles keeps rises as they get harder and harder to find which makes the truffle hunters work harder to find the few available ones. This leaves even fewer fungi to reproduce and supply the next year’s harvest.

While human activities are sometimes benign or even beneficial they can also create a burden on the landscape when key systems are disrupted by resource consumption or the removal of key species by overharvesting. Examples of negative cycles where overconsumption of natural resources has led to even worse depletion and decreasing diversity are unfortunately common. Truffles, a European fungus highly prized as a seasoning, are becoming increasingly scarce due to over-harvesting in the wild. The market value of truffles keeps rises as they get harder and harder to find which makes the truffle hunters work harder to find the few available ones. This leaves even fewer fungi to reproduce and supply the next year’s harvest. Now that you can see what it’s like to be an economic botanist, try these exercises with other common crop plants. You’ll be surprised by how much you can easily discover about things we often take for granted like bread, rubber tires or cotton cloth.

Now that you can see what it’s like to be an economic botanist, try these exercises with other common crop plants. You’ll be surprised by how much you can easily discover about things we often take for granted like bread, rubber tires or cotton cloth.