Make Your Plans to Attend—In Person or Virtually!

IN THIS ISSUE...

SPRING 2022 VOLUME 68 NUMBER 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Targeted plant collection by undergrads

& citizen scientists to understand plant

distribution...p. 24

Registration and Abstract Submission Now Open!

www.botanyconference.org

Welcome to new APPS Editor-in-Chief,

Briana Gross...p. 4

Discovering the microscopic world of live

tree bark...p. 12

Spring 2022 Volume 68 Number 1

FROM THE EDITOR

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 68

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

Seana K. Walsh

(2023)

National Tropical Botanical Garden

Kalāheo, HI 96741

swalsh@ntbg.org

Greetings,

Spring 2022 is upon us. Writing for posterity, I feel I must note a few

world events. Since our Fall issue, the United States has endured a

spike in COVID cases. Fortunately, reported case numbers have fallen

dramatically since and, in Omaha at least, we are seeing some of our

lowest numbers in a year. Anxiety over the virus and the presence (or

absence) of safety protocol continue to affect many of us. Just over

three weeks ago, Russia invaded Ukraine. I’ve heard from both Russian

and Ukrainian colleagues expressing anger and dismay over this turn

of events. We at PSB send our deepest sympathies to our readers directly affected by violence

either there, or anywhere else in the world.

We have several articles and special features in this issue that I hope you will enjoy. We welcome

a new Editor-in-Chief of APPS, and you can read about Briana Gross’ vision for that journal.

We also say goodbye to a large cohort of Botanists we have recently lost in our In Memoriam

section. Please take a moment to read about their extraordinary lives and careers.

Excitement is building over Botany 2022. This will be the first hybrid meeting in BSA history.

I am looking forward to seeing many of you in-person in Anchorage.

Sincerely,

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

BSA Welcomes Briana Gross as New

APPS Editor-in-Chief..................................................................4

Clade Biology, Phylogenetic Biology, and Systematics...............................................................................7

SPECIAL FEATURES

Discovering the Microscopic World of Live Tree Bark ............................................................................12

Filling in the Gaps: Targeted Plant Collection by Undergraduates and Citizen

Scientists to Better Understand Plant Distribution............................................................................24

The Future of Botany: Educating for a Diverse and Inclusive 21st-Century Workforce........32

SCIENCE EDUCATION

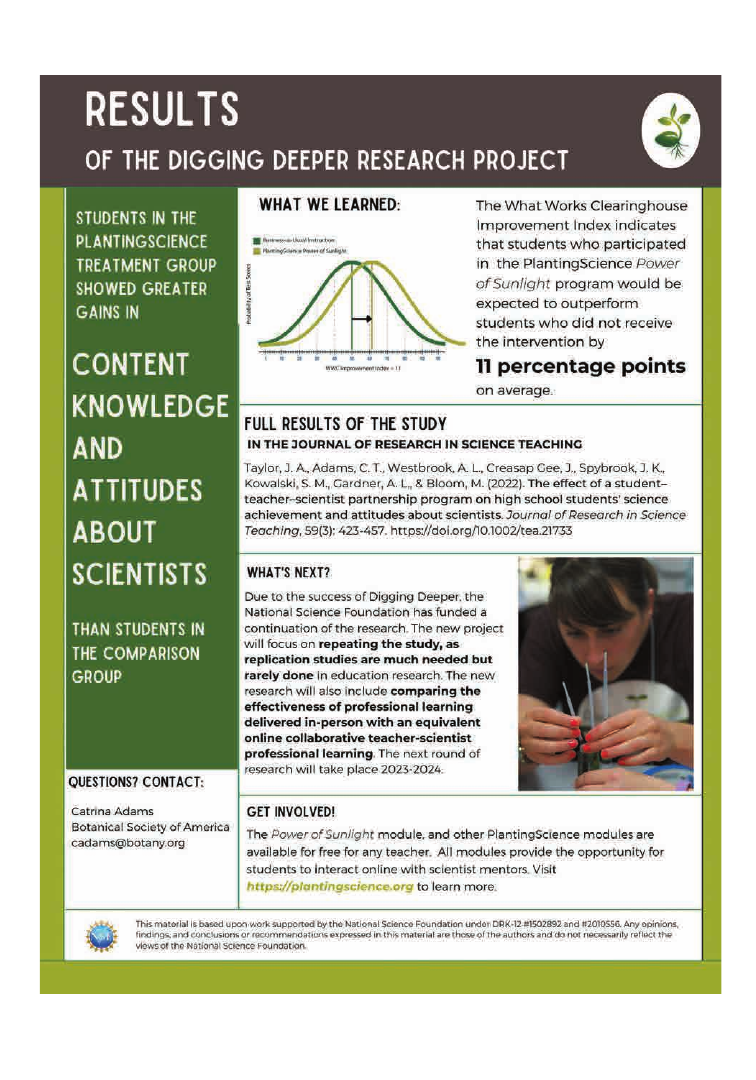

PlantingScience Digging Deeper Research Published............................................................................42

Update on PlantingScience .....................................................................................................................................42

Life Discovery Conference 2021..........................................................................................................................45

Updated Teaching Resources................................................................................................................................45

STUDENT SECTION

Roundup of Student Opportunities......................................................................................................................46

ANNOUNCEMENTS

In Memoriam Sherwin Carlquist (1930–2021).............................................................................................66

In Memoriam Jack Lee Carter (1929-2020)..................................................................................................67

In Memoriam Alan Graham (1934–2021)......................................................................................................70

In Memoriam William Louis Stern (1926–2021)........................................................................................73

In Memoriam Ronald L. Stuckey (1938–2022)............................................................................................77

In Memoriam Leonard Thien (1938–2021) .................................................................................................81

MEMBERSHIP NEWS

2021 Gift Membership Drive Results and Drawing Winner...................................................................85

Introducing Botany360: The BSA Community Event Calendar .........................................................86

BSA Award Opportunities.......................................................................................................................................87

Did You Know? ...............................................................................................................................................................87

BOOK REVIEWS..................................................................................................................................................

88

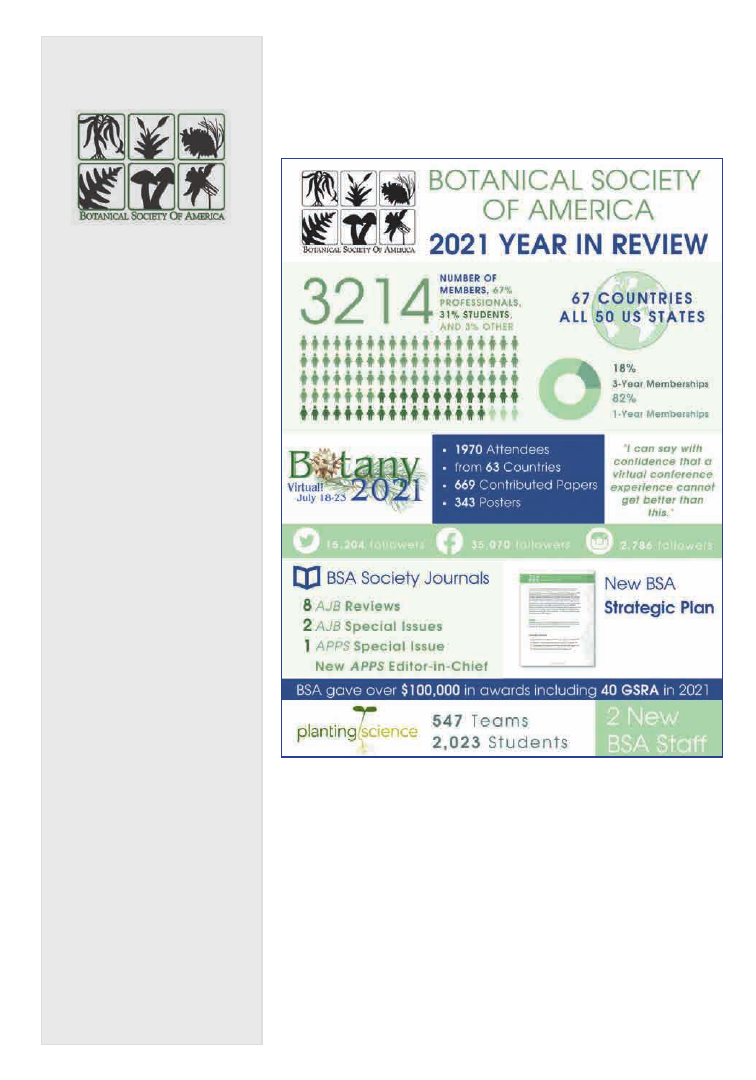

BSA YEAR IN REVIEW ........................................................................................

INSIDE BACK COVER

www.botanyconference.org

4

SOCIETY NEWS

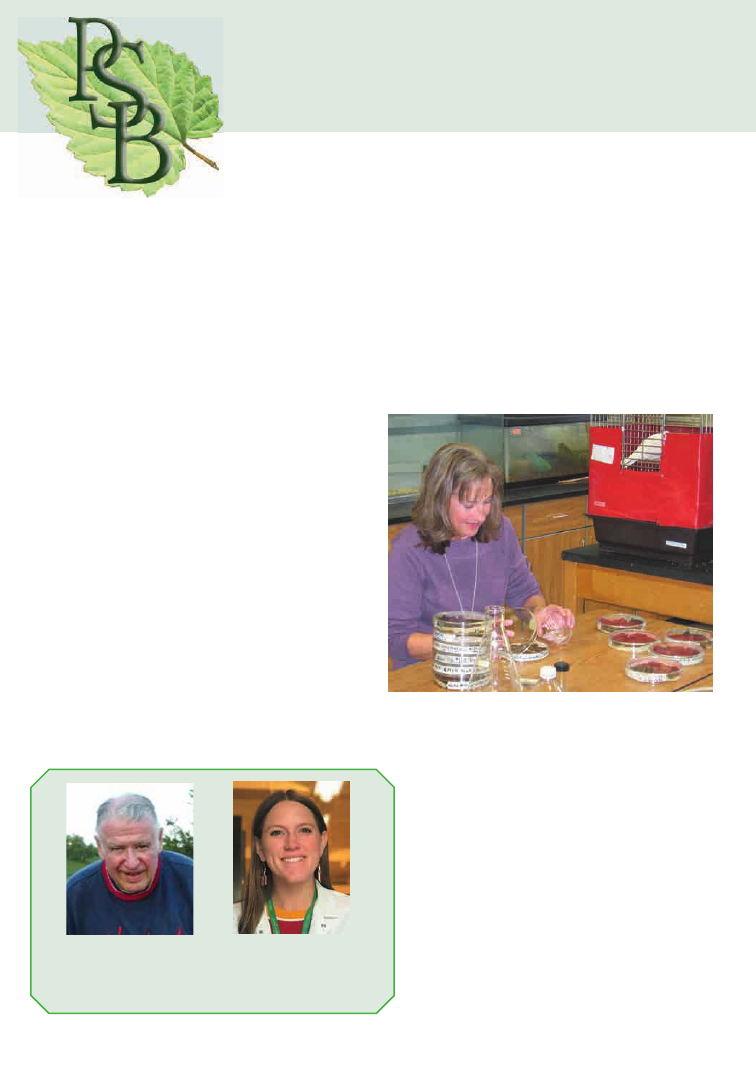

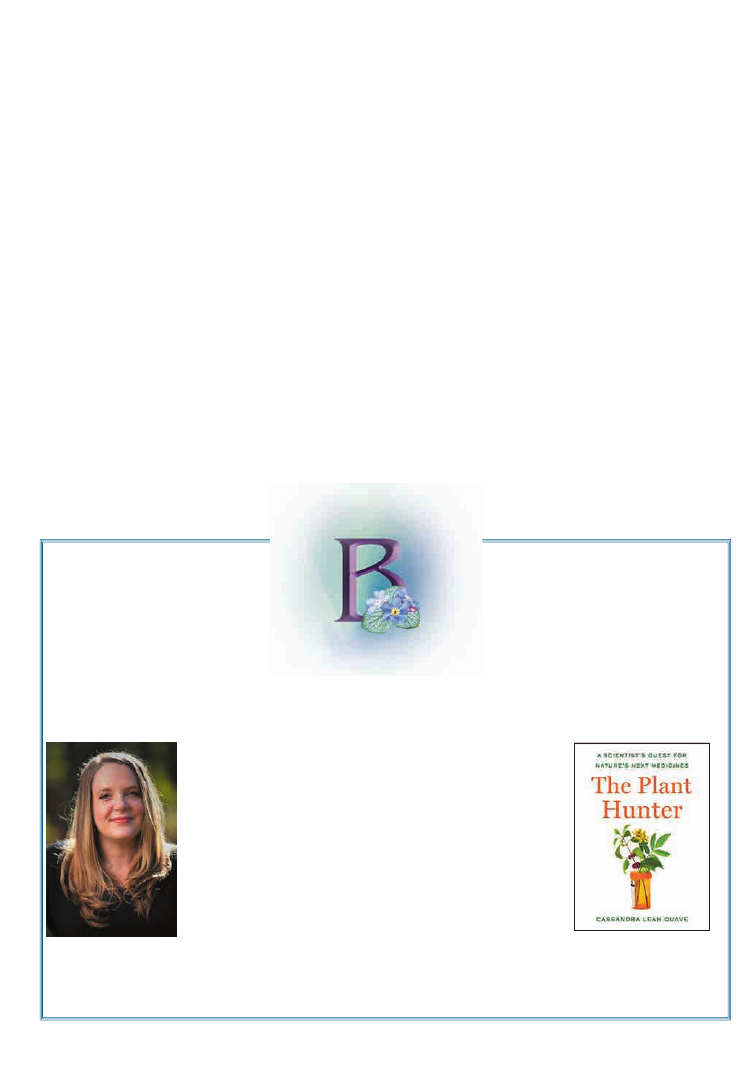

Briana Gross recently took on the role of Editor-

in-Chief of Applications in Plant Sciences

(APPS), the BSA’s first fully Open Access

journal, publishing newly developed, innovative

tools, protocols, and resources in all areas of the

plant sciences. We spoke with Dr. Gross about

her vision for the journal.

What inspired you to apply to be Editor-in-

Chief at APPS?

I was lucky to be nominated by one of my

mentors, Susan Kephart. I had seen the

advertisements for the Editor-in-Chief

position and considered applying, but I

didn’t really dig in until being nominated.

Once I gave myself time to think about it, I

realized how excited I was about APPS and

remembered how much I enjoy editorial work.

This was also an ideal time in my career to take

on this role, so I felt ready to commit. I am

relaying the fact that I was nominated because

I think it’s important for me (and others) to

acknowledge the power of nominating others

for positions that we think they are qualified

for, and I hope that I can “pay it forward” in

the future.

How would you characterize your editorial

philosophy?

At an immediate, personal level, I want the

authors, reviewers, and readers who interact

with APPS to leave with a positive impression

of the journal, even when decisions might not

go in an author’s favor. At a broader level, it

is the responsibility of the Editor-in-Chief to

be mindful of the direction of the journal and

plan strategically for its success in cooperation

with the editorial board and editorial staff.

My objective in this capacity is to work to

communicate our intentions transparently

and create an environment where all our

community members feel heard while still

moving APPS forward.

Many organizations, including the BSA, have

made it a priority to expand opportunities

for people in underrepresented groups. How

do you envision supporting and expanding

diversity and inclusion in APPS? How do

you view the opportunities and challenges

of heading up an Open Access journal, while

furthering diversity, equity, and inclusion?

BSA Welcomes Briana Gross

as New

APPS

Editor-in-Chief

PSB 68(1) 2022

5

Thanks to the work of previous Editor-in-

Chief Dr. Theresa Culley, the editorial board,

and the editorial staff, APPS already has a

good start toward expanding opportunities

for publication through increasing the

representation among its editors. However,

there is still room for us to expand by reaching

out to minority-serving institutions in the

United States and to botanical societies around

the world. These efforts will not bear fruit

immediately, but it is time to plant the seeds

now and cultivate these relationships so that

authors from these groups know that APPS is

a supportive publication venue. Publishing an

Open Access journal is a double-edged sword.

We make our publications available to anyone

with internet access, but this comes at a cost

to authors that is not always backed by their

institutions or funding sponsors. Thus, we can

expand opportunities through making science

a common commodity, but we have to find a

way to back that cost. My long-term objective

is to develop a comprehensive backstop of

funding sources to help cover the publication

costs for articles that are appropriate for APPS

to help fill this gap.

As APPS approaches its 10-year publication

anniversary, this is a time to reflect on

achievements while looking to the future.

What do you see as strengths of the journal

and goals for the next 10 years?

APPS has so many strengths: the quality of

the publications in APPS is high and it has

continued to increase over the years, it has a

great reputation in the botanical community

as a reliable resource for new protocols and

software, and it integrates across the diversity

of fields of plant science. In the next 10

years, I want to see APPS as the destination

for authors and readers interested in plant

genomics (both resources and software) and

the continually evolving catch-all of “big

data” in botany, ranging from herbarium

digitization to ecological modeling for plant

communities. Beyond the subject matter that

we cover, which will inevitably evolve in the

next decade, my goal is for APPS to increase

its profile in the botanical community so that

we are the destination of choice for any new

methods in plant science. As a young journal,

we have enormous potential, and I know

that we have capacity and ability to facilitate

excellent experiences for authors, editors, and

readers as we grow.

APPS is proud to be a Society journal. How

do you think APPS can best serve members

of the BSA community (and beyond),

and why do you think it’s important for

BSA members to support their Society

publications?

APPS can serve its members by being mindful

and responsive to their needs, while also

making sure that the journal continues to

grow its impact factor and feature high-quality

publications. I hope that I can learn more

about what our members want and how we

can provide this every year going forward. We

also strive to give authors a great experience

PSB 68 (1) 2022

6

when they send their work to us. On the flip

side, we depend on our members to send us

their work and to promote APPS to colleagues

who might not be aware of us yet. We are all

part of a team, and as a member-owned Society

we all benefit from small actions that support

our publications. If each of our members

thought of APPS as the primary target for

the new method they cooked up in their labs,

we would be happy to see those submissions

and I think that the ultimate publications will

benefit from the excellent reputation of the

journal.

What are you most looking forward to as

Editor-in-Chief?

There are many different things that I like

about writing and editing, and serving as

Editor-in-Chief will be enjoyable for those

reasons. However, one of the main things

that I look forward to is working with smart,

talented botanists who care about their work

and have great ideas for the field and for

APPS. Working with enthusiastic, intelligent

colleagues is one of the best things we can

experience in our professional careers, and I

think that serving as Editor-in-Chief for APPS is

a place where I can experience this to the fullest.

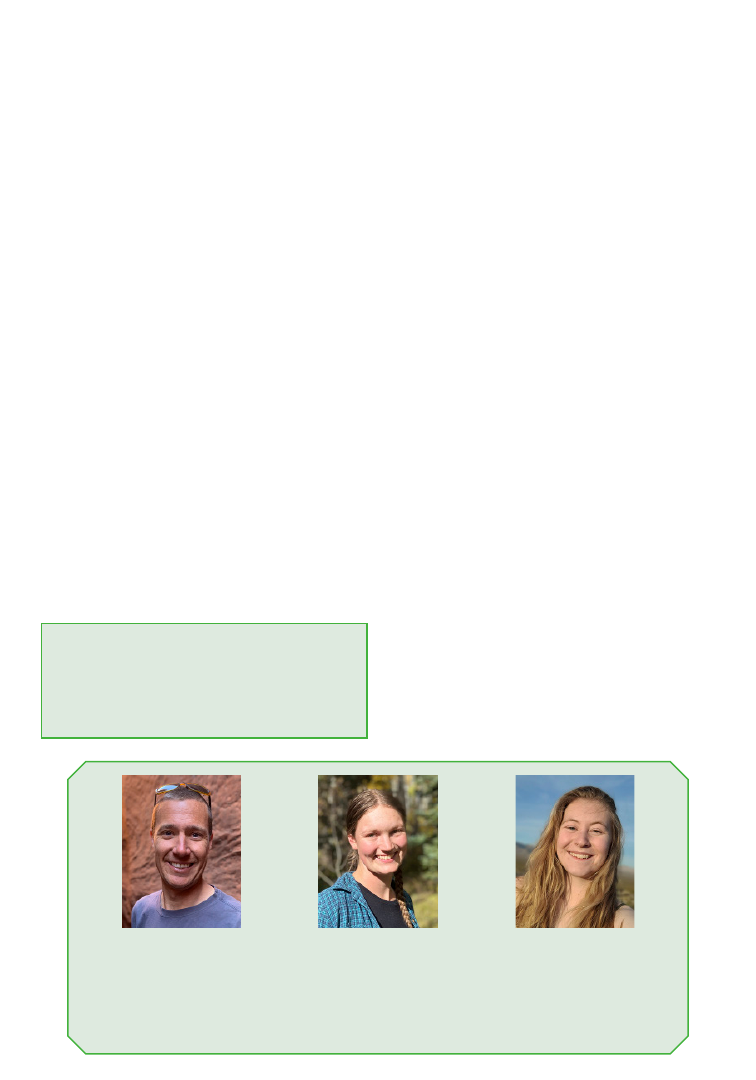

NEW EARLY CAREER ADVISORY BOARD (ECAB) FOR

2022-2024

The BSA's Early Career Advisory Board (ECAB) is a group of early-career botanists that engages

with and advises the editors of the American Journal of Botany, Applications in Plant Sciences,

and the Plant Science Bulletin in a number of ways, including recommending timely topics for

review papers, identifying papers in pre-print archives that may be appropriate to publish in

our journals, and advising on issues of importance to the publications team.

We had a tremendous response to our recent call for students and postdocs to join the ECAB,

and we are grateful to all who applied. We are pleased to officially welcome the new group!

Row 1: Ajith Ashokan, Liming Cai, Mario Blanco-Sánchez, Urooj Fatima, Ana Flores

Row 2: Jorge Flores, Catalina Flores-Galván, Shelly Gaynor, Huasheng Huang, Luiz Rezende

To learn more about the 2022-2024 ECAB Members, see https://botany.org/home/publications/ecab.html.

PSB 68(1) 2022

7

In his incoming BSA presidential address at

Botany 2021, Michael introduced the phrase

“clade biology.” The idea was to draw attention

to an approach that the two of us have been

thinking needs more attention, and which we

think differs importantly from the area now

widely referred to as “phylogenetic biology.”

How do these two differ? Clade biologists

are those among us who obsess over some

particular group of organisms, wanting to

know as much about them as possible. They are

fascinated to learn any little thing about these

organisms, no matter how inconsequential

this may seem to others. They tend to work on

their organisms for a long time (often over an

entire career), and come at them from multiple

angles (functional morphology, development,

ecology, biogeography, etc.). Of course, their

work tends to be organized phylogenetically,

Clade Biology, Phylogenetic

Biology, and Systematics

and their knowledge of relationships may

eventually yield species delimitations and

a phylogenetic classification system, but in

our view these are natural outcomes of clade

biology, not its primary objectives. Clade

biologists tend naturally to build teams of

collaborators, drawing in other disciplines as

they take deep dives into one aspect or another

of the biology of their organisms. If a clade

biologist has the good fortune of training

students, their students might become

engaged in some dimension of the research

and might then take that along to their own

labs, in which case teams can expand through

multiple labs and academic generations. Over

the years, the group of organisms might ascend

to the level of a “model clade.” Like model

species (think Arabidopsis thaliana), these can

then serve as vehicles for testing hypotheses of

all sorts, taking full advantage of the wealth of

accumulated knowledge. But in this case, they

are mostly used to test hypotheses concerning

patterns and processes at the level of whole

clades.

Phylogenetic biologists, in our view, take

a different approach to understanding

clade-level phenomena. They tend to take a

hypothesis-testing approach from the outset,

focusing on a particular question rather than

on a particular clade, such as the evolution of

dioecy or shifts in the rate of diversification.

They often assemble very large phylogenetic

By Michael J. Donoghue & Erika J. Edwards

Department of Ecology & Evolutionary

Biology, Yale University, PO Box 208106,

New Haven, CT 06520, USA

Address of the Incoming BSA president

Michael Donoghue, with Erika Edwards

PSB 68 (1) 2022

8

trees (e.g., harvesting data from sources

such as GenBank), with multiple instances

of dioecy, for example, scattered throughout.

Alternatively, they may assemble and compare

phylogenetic trees of multiple individual

clades that include dioecious species. In many

cases, data on the trait (or traits) under study

are gathered not from nature but from surveys

of the literature, or perhaps from specialized

trait databases. The many other details of the

organisms under study—the ones that would

fascinate the clade biologist—are mostly

viewed as (or assumed to be) irrelevant to the

particular phenomenon under investigation.

Phylogenetic biologists also have a tendency

to move from one problem to another during

their careers, switching from one group of

organisms to another as appropriate. That

is to say, they are not so deeply committed

to working on one group of organisms for

a long time. They collaborate with clade

biologists and experts from other disciplines,

as necessary, but these alliances change as

they move from one suite of traits or clade to

another. And, to the extent that their studies

involve students, the threads that pass from

one generation to the next tend to revolve

around particular methodologies.

Are you a clade biologist or a phylogenetic

biologist? Or course, you don’t have to be

either one—there are plenty of other things to

be—and you could certainly be both. We have

purposefully set these out as two exclusive

categories, but in actuality there’s a continuum

between them. It’s also quite possible to be a

clade biologist who occasionally ventures

into phylogenetic biology. We think we’ve

done this during our own careers. It’s less

possible, we think, to go the other direction

because, almost by definition, it’s hard to

dabble in clade biology, or at least to do it very

effectively, without pretty complete devotion

to a particular clade, or possibly a few different

clades over the course of a lifetime.

Where is “systematics” in all of this? We

suspect that many BSA members identify

as systematists, although this may be less so

among younger members—at least, in our

recent experience, postdocs and graduate

students don’t identify as strongly with

systematics as they used to. To be sure, they

are happy to publish in journals with the word

systematics in the title, such as Systematic

Biology, but they don’t really see themselves as

systematists.

Traditional systematics doesn’t map very

neatly onto phylogenetic biology, as we delimit

this here, although we suspect that some who

identify as systematists would also consider

themselves to be (at least partly) phylogenetic

biologists. Systematics comes much closer,

we think, to clade biology, especially in as

much as training in systematics often begins

with the choice of a group of organisms on

which to become the world’s expert. On the

other hand, we suspect that our definition

of clade biology will seem overly broad to

many systematists in the sense that it doesn’t

specifically highlight species delimitation

and classification, which have long been the

bread and butter of systematics. In our view,

species delimitation and naming are critical

elements of clade biology, but our definition

puts a greater emphasis on understanding

the complete biology of the organisms in

question (including work at the intersection of

molecular biology, development, physiology,

ecology, etc.), whether or not this knowledge

bears very directly on species delimitation

or classification (although, naturally, it very

often will).

PSB 68(1) 2022

9

If one did wish to equate systematic biology

with clade biology (i.e., if these were viewed

as one and the same; Box 1, option 1), which

name would we chose for this field? One

might argue that we don’t need a new term—

we should just stick with systematics for this

field. On the other hand, we think that clade

biology has a distinct advantage in that it

refers unambiguously to the object of study:

clades. In this sense it is comparable to terms

such as “population biology,” “cell biology,”

etc., where the object of study is clearly

named. “Systematics” is ambiguous on this

score, as “system” itself is pretty vague and

all-encompassing. So, if we had to choose, we

think that clade biology would be the better

choice.

Another possibility would be to make a

hierarchy out of these disciplines (Box 1,

options 2 and 3). But does clade biology

naturally encompass phylogenetic biology, or

vice versa? We think not. As for “systematics,”

we see two possibilities. One would be to use

it to signify the subdiscipline within clade

biology focused squarely on species discovery

and classification. Another possibility, which

we prefer, would be to retain systematics for

the more inclusive field that encompasses both

clade biology and phylogenetic biology. In

any of these cases, we want to emphasize that

we see both clade biology and phylogenetic

biology as totally worthwhile and necessary

endeavors. There’s no better or worse here—

just alternative approaches to studying clade-

level phenomena. Which way you lean just

depends on what you find most satisfying.

Of course, it’s perfectly okay to not worry

at all about where you fit into this schema,

and to chart your own path. And, in doing

so, you might find yourself flirting with

other somewhat ill-defined terms, such as

“integrative biology” or “comparative biology.”

We won’t tackle these here, except to note that

integrative biology aligns pretty well in some

respects with clade biology, although some

who identify with this term are not so focused

on individual clades. Likewise, comparative

biology aligns in some respects with

phylogenetic biology in our sense of the word.

It’s a confusing landscape of terminology, to

be sure.

Our main point here is that it’s worth

recognizing clade biology as a distinct

endeavor, with its own peculiar and enduring

scientific value. To illustrate this, we’ll

briefly highlight the work of our recently

deceased zoological colleague, David Wake.

Box 1. Where does “systematics” fit in? Of these three options, we prefer number 3.

1. Clade Biology (= Systematic Biology)

Phylogenetic Biology

2. Clade Biology

Systematic Biology (species delimitation, classification)

Phylogenetic Biology

3. Systematic Biology

Clade Biology

Phylogenetic Biology

PSB 68 (1) 2022

10

Dave, along with his spouse and colleague,

Marvalee, both of UC Berkeley, devoted their

careers to understanding amphibians, but

especially salamanders, and especially lungless

salamanders (Plethodontidae). If you haven’t

followed this work, you should look into it,

and you’ll find one discovery after another

grounded in their deep commitment to, and

knowledge of, these organisms, built up over

more than five decades (Griesemer, 2013).

James Hanken (quoted in Sanders, 2021),

long the Director of Harvard’s Museum of

Comparative Zoology, described Dave Wake

in these words:

“He chose a particular lineage of organisms—

in this case, the family Plethodontidae—

and pursued it in all respects in order to

understand how the group diversified and

why it did the way it did. It was molecules

to morphology to ecology to behavior to

development, overlaid by taxonomy—his was

a deliberate conviction that in order to really

understand the evolution of organisms, you

have to focus on a particular group and get to

know it extremely well.”

This captures perfectly the way that we’re

thinking about clade biology: complete

immersion in a group of organisms, studied

from every possible angle. Add to this a team-

building mentality and lots of enthusiasm

and you’re in for a lifetime of pleasure and

discovery. And the beauty of such a long-

term commitment is that it leads naturally

to discoveries of very broad significance. As

Michael Nachman (quoted in Sanders, 2021),

Director of the UC Berkeley Museum of

Vertebrate Zoology, put it: “Salamanders were

his love and passion, but he was really a deep

thinker who used salamanders as an entry

way to thinking about the biggest questions in

evolutionary biology.”

Clade biology, done well, starts with some

organism-of-interest problem, but works its

way out to questions and answers in realms

that were never anticipated. Wake, for

example, was at the epicenter of the formation

of the field of evolutionary developmental

biology, and of the study of parallel and

convergent evolution, and of speciation (e.g.,

“ring species” in Ensatina). He also alerted

the world to the global decline of amphibian

populations. All of this flowed naturally from

his deep knowledge of salamanders.

One last thought concerns the career choices

faced by students and early-career scientists,

who may consider a long-term commitment

to a clade—with uncertain outcomes—to be

too risky in this day and age. We certainly

understand this worry but would offer the

following advice. If you are passionate about

a group of organisms, keep that passion alive

even as you pursue other things that might

lead to more immediate accomplishments.

We think you’ll find that the deep knowledge

that you accumulate will provide you with a

special lens through which to view biological

phenomena of all sorts, and will serve as an

unending source of fresh ideas. Get to know

a group of organisms “extremely well,” we’re

certain you won’t regret it!

Our overall conclusion is that clade biology

is a highly productive way of knowing,

which provides a necessary compliment to

other approaches, including what we have

distinguished here as phylogenetic biology. We

are confident that we won’t lose this approach

so long as at least some people continue to

obsess over particular groups of organisms,

which seems inevitable. However, what we

must do is to properly value, encourage,

and support this approach, and consciously

improve it not just for or own happiness but

for the betterment of science at large.

PSB 68(1) 2022

11

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to the BSA for the

opportunity to present these views, and to

the many students and colleagues who have

discussed these topics with us over the years.

REFERENCES

Griesemer, J. 2013. Integration of approaches

in David Wake’s model-taxon research plat-

form for evolutionary morphology. Studies in

History and Philosophy of Biological and

Biomedical Sciences 44: 525–536.

Sanders, R. 2021. David Wake, a prominent

herpetologist who warned of amphibian de-

clines, is dead at 84. Berkeley News, May

4, 2021. Website: https://news.berkeley.

edu/2021/05/04/david-wake-a-prominent-

herpetologist-who-warned-of-amphibian-de-

clines-is-dead-at-84/.

Are you registered for Botany 2022

Plants at the Extreme?

Don't miss out on the amazing field trips, workshops, scientific sessions, compelling

speakers and all the social and networking events - just like in the past!

As a bonus, it will be a hybrid conference, which means everything that is recorded at

the conference will be available to view and review for a year after the conference on the

online platform.

Register now! Conference information including hotels and dorms can be found at:

www.botanyconference.org

12

RATIONALE FOR

INSTRUCTIONAL

EXPERIENCE

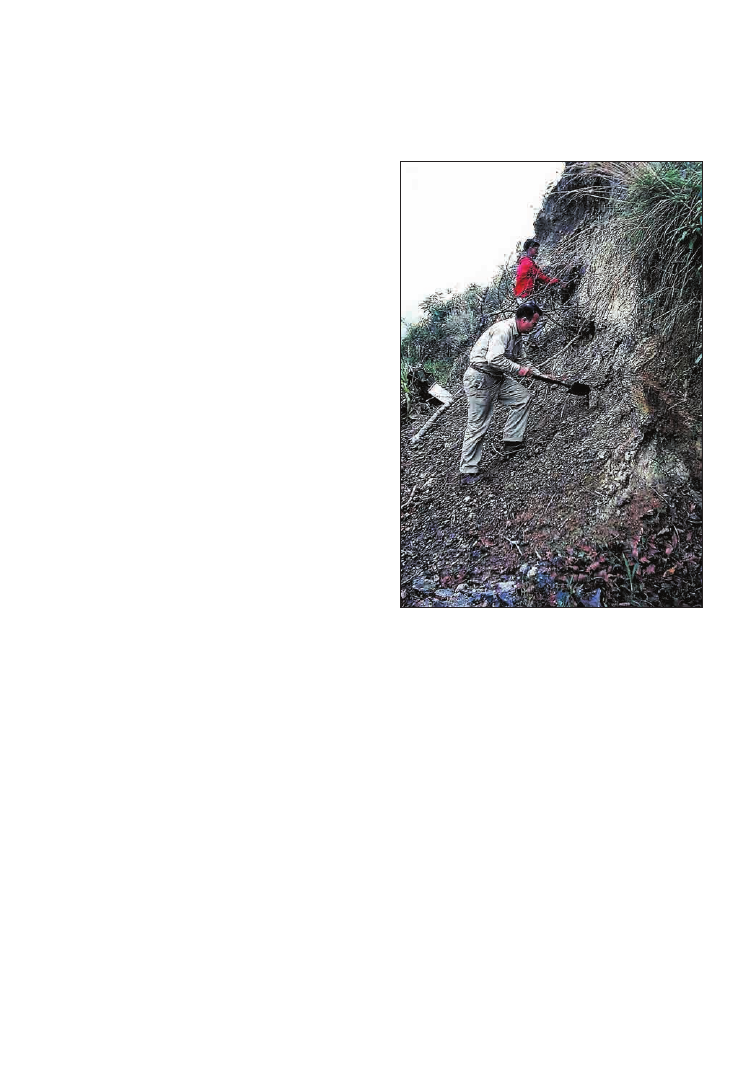

Patricia (Trish) A. Smith, now retired, was

a seventh-grade Life Science teacher at

Warrensburg RVI Middle School (WMS), at

Warrensburg, MO during 2004–2007. Her

expertise in finding grant funds supported

her laboratory classroom activities with

extramural funding. These grant funds came

from the Missouri Department of Elementary

and Secondary Education and local private

organizations. She shared her classroom

Discovering the Microscopic World

of Live Tree Bark

A Model Instructional Experience for Students and Teachers

Using a Virtual iAdventure, Teacher Preparation Guide,

Student Worksheets, and Moist Chamber Cultures

By Harold W. Keller and Ashley Bordelon

Botanical Research Institute of Texas,

1700 University Drive, Fort Worth, Texas 76107

and laboratory experiences on how live

animals and trees were integrated into her

laboratory activities in presentations given

nationally and in Missouri (Figure 1). Her

connections to the University of Central

Missouri (UCM) led her to explore a possible

National Science Foundation-Research

Experience for Teachers (NSF-RET) grant

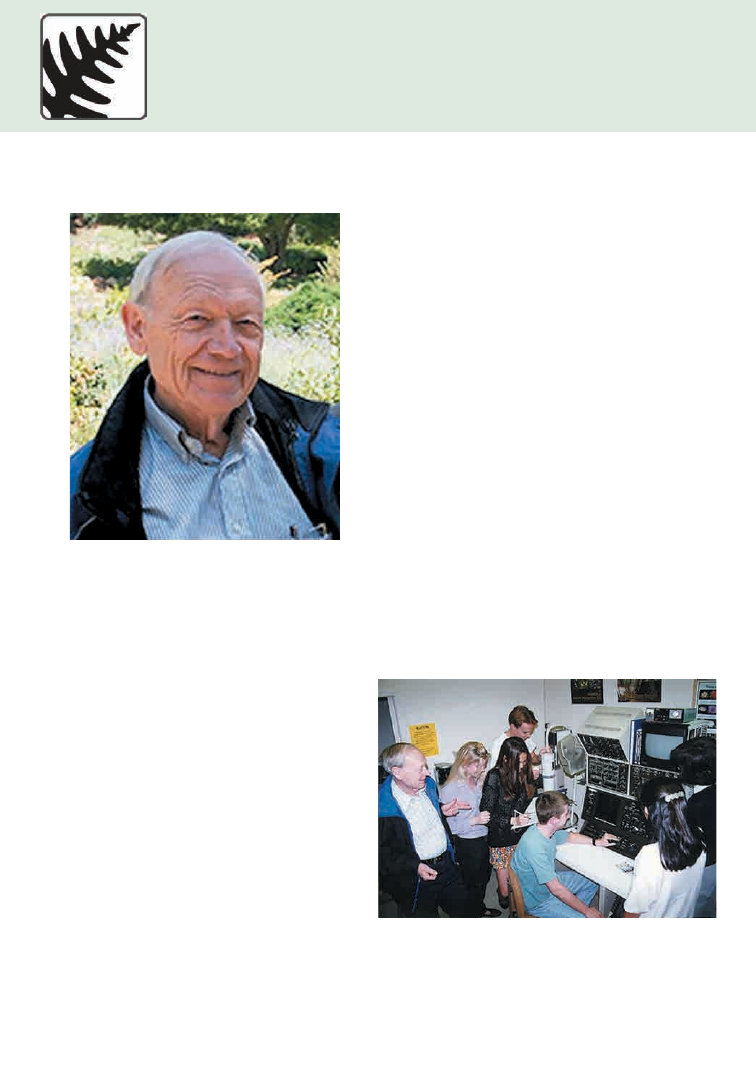

Figure 1. Trish Smith in her classroom labora-

tory wetting moist chamber tree bark cultures.

Note labeled plastic Petri dishes with moist

chamber tree bark ready for observation.

(Photo by H.W. Keller.)

SPECIAL FEATURES

PSB 68(1) 2022

13

as a supplement to the iAdventures that was

already part of her synergistic laboratory

experiences. The intent of the NSF-RET was

to provide funds for professional development

targeted for teachers K–12 on the cutting edge

of science, to strengthen partnerships between

institutions of higher learning and local school

districts. She consulted in 2004 with then

NSF grant-holder, and Principal Investigator,

Harold W. Keller at UCM, who had an NSF

grant titled “Biodiversity and Ecology of Tree

Canopy Biota in the Great Smoky Mountains

National Park.” The objectives of this tree

canopy biodiversity research project were

chronicled in previous publications and will

not be repeated here (Keller, 2004, 2005, 2019;

Smith and Keller, 2004; Kilgore et al., 2008).

This partnership appeared to be a good fit

for an NSF grant proposal to the Division of

Environmental Biology, Biodiversity Surveys

and Inventories Program.

Prospective applicants for RET grants must

prepare a cooperative grant proposal after first

consulting with the appropriate NSF Program

Officer. This grant proposal application

included a three-page descriptive narrative, a

two-page teacher curriculum vitae, a prepared

budget, and justification for up to a limit of

$10,000. This RET supplemental funding

application was submitted electronically

through the grant-holder’s university by NSF

Fastlane.

Current application instructions are included

in opportunity announcement NSF18-089.

Some of these details have changed (for

example, teacher budget costs are now up to

$15,000). The following quotation represents

in part current NSF priorities: “Another goal

of the RET supplement activity is to build

collaborative relationships between K-12

science educators and the NSF research

community. BIO is particularly interested in

encouraging its researchers to build mutually

rewarding partnerships with teachers at urban

or rural schools and those in school districts

with limited resources.”

EXPERIENCING TREE

CANOPY BIODIVERSITY

IN GREAT SMOKY MOUN-

TAINS NATIONAL PARK:

CONNECTING SEVENTH

GRADE STUDENTS

THROUGH AN

iADVENTURE

This activity was part of the virtual field

tree canopy experience in the Great Smoky

Mountains National Park (GSMNP -

iAdventure) during 2004. The field collection

of live tree trunk bark samples of Eastern Red

Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) trees took place

at Pertle Springs, the land laboratory for UCM

(see Teacher Preparation Guide and Student

Worksheets below). Seventh-grade life science

students from WMS were bused to Pertle

Springs where they collected live tree bark

samples and prepared moist chamber bark

cultures in the classroom laboratory. Many life

forms, including myxomycetes, were observed

during laboratory class sessions.

The iAdventure live link with all its web

content was removed from the Warrensburg

Middle School site when Trish and Stan

Smith retired. However, the papers, images

and documents and original Uniform

Resource Locator were preserved by the

authors. In September 2021, Jason Best,

PSB 68 (1) 2022

14

the Director of Biodiversity Informatics at

the Botanical Research Institute of Texas

(BRIT), was able to revive the original website

through GitHub (https://britorg.github.io/

GSMNP_iAdventure). Interested persons can

now access and experience the full content

of the iAdventure in GSMNP, as well as the

Teacher Information Page that has Student

Worksheets related to the collection of field

samples. The intent is to extend the benefits

of these field experiences for students and

teachers worldwide through this linked

inquiry-based iAdventure available as an

interactive web-based activity. Additionally,

historical snapshots of the iAdventure site

can be accessed through Archive.org at:

https://web.archive.org/web/2016*/http://

warrensburg.k12.mo.us/iadventure/

gsmnpiadventure/.

SYNOPSIS OF

iADVENTURE, TEACHER

PREPARATION GUIDE,

AND STUDENT

WORKSHEETS CONTENT

In the summer of 2004, Trish and Stan Smith

arrived at GSMNP, pitched a tent, and recorded

daily activities of the tree canopy research

team as part of the iAdventure. Exploring Life

in the Forest Canopy highlights and tracks the

activities of five undergraduate UCM students

(Amber, Ashley, Cheryl, Erin, and Tommy) as

they participate in the tree-climbing school

at Pertle Springs and the field experience

climbing giant trees in the GSMNP collecting

tree trunk bark samples. On the iAdventure

website, visitors can explore topical headings

such as Research Objectives; GSMNP All Taxa

Biodiversity Inventory, with geographical area

description; Field Trip Organization Pre-trip

Planning; Knott Clinic; Tree Climbing School;

Meet Charly Pottorff, professional arborist;

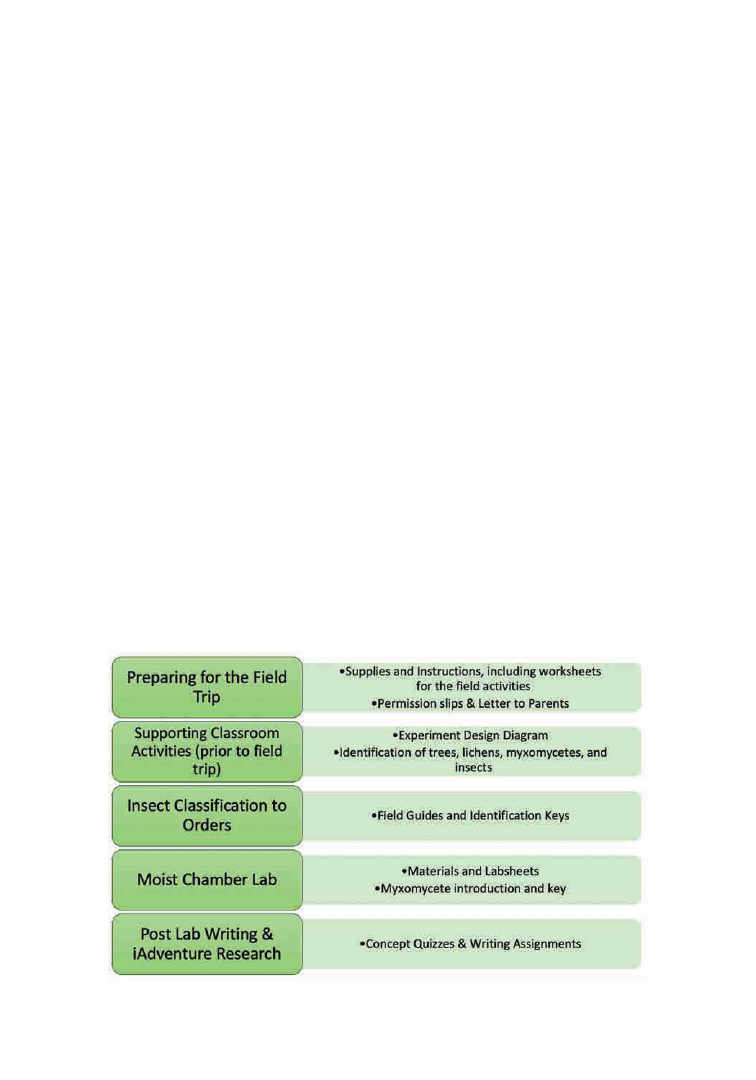

Figure 2. Summary of resources provided for teachers on the Teacher

Information Page, iAdventure website.

PSB 68(1) 2022

15

meet Dr. Steve Wilson, entomologist world

authority on plant hoppers; meet Dr. Joe Ely,

biometrician and plant ecologist; Field Work,

climbing trees and collecting bark samples,

as well as preparing and raising insect flight

intercept canopy traps; Life at the Research

Station; about Trish and Stan Smith; and

Stories from the Field, about the discovery of a

new tree canopy myxomycete species, Diachea

arboricola, by Melissa Skrabal, among others.

The Teacher Information Page has a list of

resources needed, as well as a list of questions

for students about their observations of the

iAdventure. It also includes links to worksheets

that provide more detailed information about

how to prepare for the field trip, as well as

information about lichens, myxomycetes, and

insects (Figure 2). Some examples included a

List of Field Tasks; Supply List; Tree Tags; Field

Task Instruction Sheets: Meadow Sweepers;

Canopy Catchers; Barking up the Right

Tree; Myxo-O-Masters; Red Cedar Database

Sheet; Lichen Log; Tree Sleuths; Entomology

Worksheet; Insect Identification Key; Moist

Chamber Laboratory Supplies (used for

preparation of moist chamber cultures); Bark

pH Procedure Document; Examination of Moist

Chamber Cultures Labsheet; and Key to the

Myxomycete Orders, among others. Lectures

describing the illustrated myxomycete life

cycle, color images of myxomycete fruiting

bodies using Smart Board presentations,

and question-and-answer sessions enabled

students to interact with the presenter.

References were available for student reading

and picture keying of myxomycete fruiting

bodies observed in moist chamber cultures

(Keller and Braun, 1999).

The two main student activities are nested

under the Title Page (Tier One) and

iAdventure (Tier Two) (Figure 3). The Tier 1

Figure 3. Snapshot of the ‘Site Map’ of the

iAdventure website

iAdventure website allows worldwide access to

the tree canopy field experiences in GSMNP

and the parallel field research at Pertle

Springs. This was a problem-solving activity

that helped students determine the direction

and outcome of a content-rich storyline

using resources available on the internet,

particularly resources providing real-world

data and primary documents. Participating

students should experience the three phases of

research emphasized in the original GSMNP

NSF grant: the Adventure Phase (tree climbing

using ropes and collecting bark samples

for moist chamber cultures (Kilgore et al.,

2008); the Laboratory Phase (sample sorting

and preparation of moist chamber cultures);

and the Publication Phase (poster and oral

platform presentations for local, regional, and

national scientific meetings).

The Tier 2 site emphasizes the collection of

live tree trunk bark of Eastern Red Cedar,

American Elm (Ulmus americana), and

White Oak (Quercus alba) at Pertle Springs.

Students were divided into four groups and

then subdivided into task groups of one or

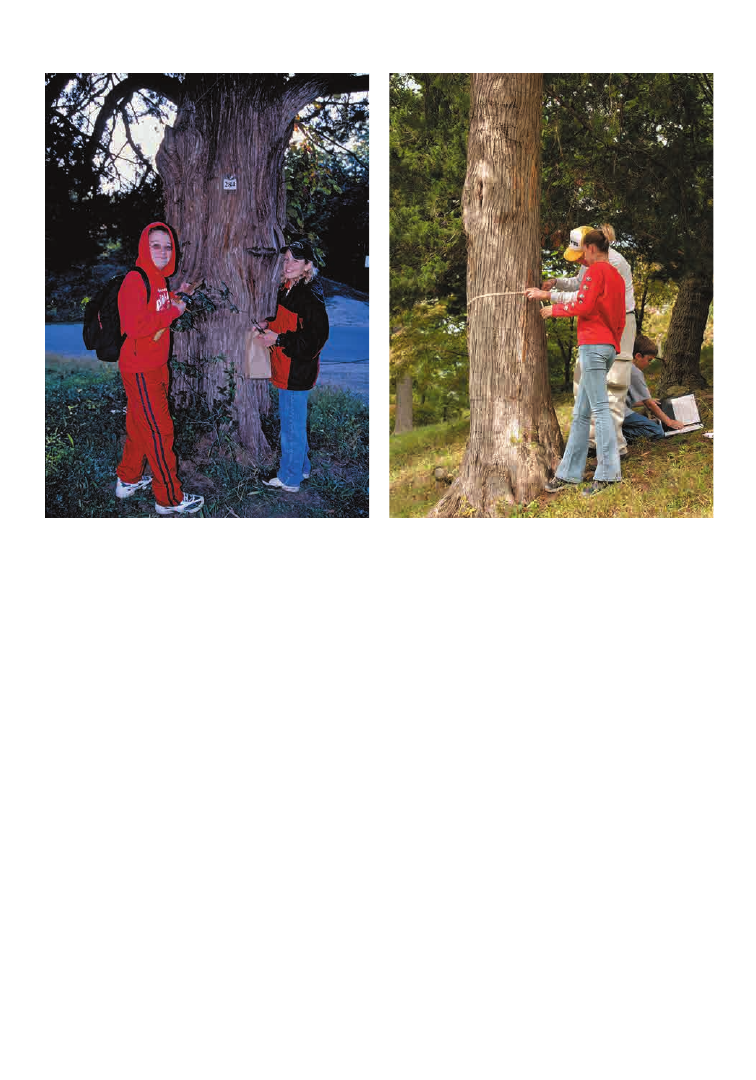

two students (Figures 4 and 5). UCM faculty

PSB 68 (1) 2022

16

Figure 4. Two seventh-grade WMS students

collecting trunk bark samples from a live East-

ern Red Cedar tree at Pertle Springs. Note tree

tag number, collecting gear, and students enjoy-

ing this field experience. (Photo by H.W. Keller.)

and students from the Biology Department,

along with student parents, assisted with field

collections. Six groups of 20 WMS students

were transported to Pertle Springs for one-

hour field trips on September 28 and 29,

2004, for a total of 240 students. Safety of the

seventh-grade WMS students was a priority.

Therefore, they did not climb trees, use knives,

or shoot slick lines with the Big Shot… much

Figure 5. Author and student measuring tree

trunk diameter of Eastern Red Cedar tree

at Pertle Springs. Note student on ground

recording tree data. (Photo by T. Smith.)

to their dismay! Tree bark samples were

used to prepare moist chamber cultures so

students could observe a miniature ecosystem

composed of myxomycetes, fungi, lichens,

mosses, liverworts, green algae, cyanobacterial

algae, myxobacteria, tardigrades, insects, and

nematodes, among others. This is only an

overview of the two tiers; more information is

available on the website.

PSB 68(1) 2022

17

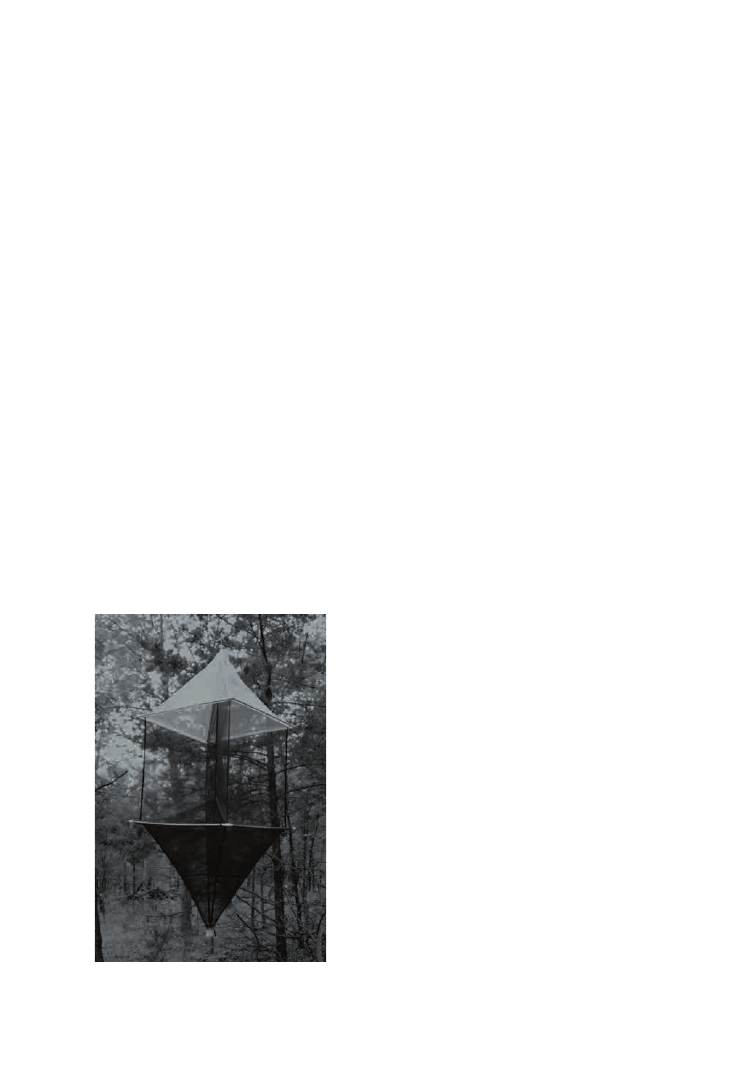

INSECT FLIGHT

INTERCEPT TRAPS

Steve Wilson at UCM was in charge of the

aerial installation of the Sante insect flight

intercept tree canopy traps at GSMNP, Big Oak

Tree State Park, and Pertle Springs (Figure 6).

Students assisted in raising the fine-meshed

canopy traps with two open pyramid structures

(9 feet high by 4 feet wide) with a top and

bottom 500-mL collector bottle (killing jar)

filled with 70% isopropyl alcohol. This canopy

trap was tethered to a horizontal branch at 50

to 60 feet for five days. Top canopy collection

bottles tended to trap insects that hit the trap

then climbed upward such as leafhoppers, tree

hoppers and planthoppers, and moths; flies

and beetles tended to hit the trap and drop

downward into the bottom bottle (Wilson et

al., 2003). Students also collected from ground

sites using sweep nets. The collected insect

specimens were used to perfect the taxonomic

keys and create a basis for understanding

diversity and adaptation. .

PERTLE SPRINGS FIELD

COLLECTIONS AND

LABORATORY

PREPARATION OF MOIST

CHAMBER CULTURES

USING LIVE TREE TRUNK

BARK

General credit for the use of moist chamber

bark cultures from living trees goes back to the

early 1930s, when tiny species of myxomycetes

new to science were discovered by graduate

student Henry C. Gilbert working under

the supervision of Professor Dr. George W.

Martin at the University of Iowa Mycological

Laboratory (Gilbert and Martin, 1933; Gilbert,

1934). Since then, many papers and books

have described preparations of moist chamber

cultures that may differ in methodology but

involve wetting field collections of bark from

living trees (Keller, 2004; Keller et al., 2004;

Everhart et al., 2009; Scarborough et al., 2009;

Snell and Keller, 2003), herbaceous plants

(Kilgore et al., 2009), and decaying wood

or leaves from ground sites, usually at times

when myxomycete fruiting bodies are not

present (Keller et al., 2008). This technique

gives the observer the opportunity to create

a self-contained moist environment where

the myxomycete plasmodium and developing

fruiting body stages are present, although they

are not always seen in the field.

Seventh-grade WMS life science students field-

collected live tree trunk bark from Eastern Red

Cedar trees at Pertle Springs (Figures 4 and 5).

This is a short 10-minute bus trip from WMS

to a series of trees that line the paved roadway

at the entrance of the area (Scarborough et al.,

2009). This tree species was targeted because it

Figure 6. Flight intercept tree canopy insect

trap installed in a tree at Pertle Springs. (Photo

by H.W. Keller.)

PSB 68 (1) 2022

18

has the highest species diversity of life forms,

which provided students with the best chance

of success observing moist chamber bark

cultures (Keller and Braun 1999; Keller and

Marshall, 2019; Scarborough et al., 2009; Perry

et al., 2020). Two-student team members were

briefed on the safe collection of tree trunk bark

following instructions on Data Worksheets

that recorded species of tree, overall estimated

size of the tree (height and diameter; Figure

5), characteristics of bark surface, presence

of other life forms (for example, lichens), and

height on tree where the bark sample was

collected.

Bark samples collected in paper bags were

transported to the WMS class laboratory,

where students prepared moist chamber

cultures in oversized sterile plastic Petri dishes

(150 × 25 mm) that were lined with sterile

filter paper. About six pieces of bark sample

covering the bottom of the dish were arranged

without overlapping. Thirty mL of sterile

deionized water was added around the bark,

avoiding directly wetting the bark surface

areas. These moist chamber bark cultures

were allowed to soak for 24 hours, and any

excess water was decanted during the next

laboratory period. Observations were made

during normal laboratory class sessions twice

a week for approximately four weeks. Students

recorded pH values using litmus color-coded

papers and observed life forms over this

period using the naked eye and 20 to 50×

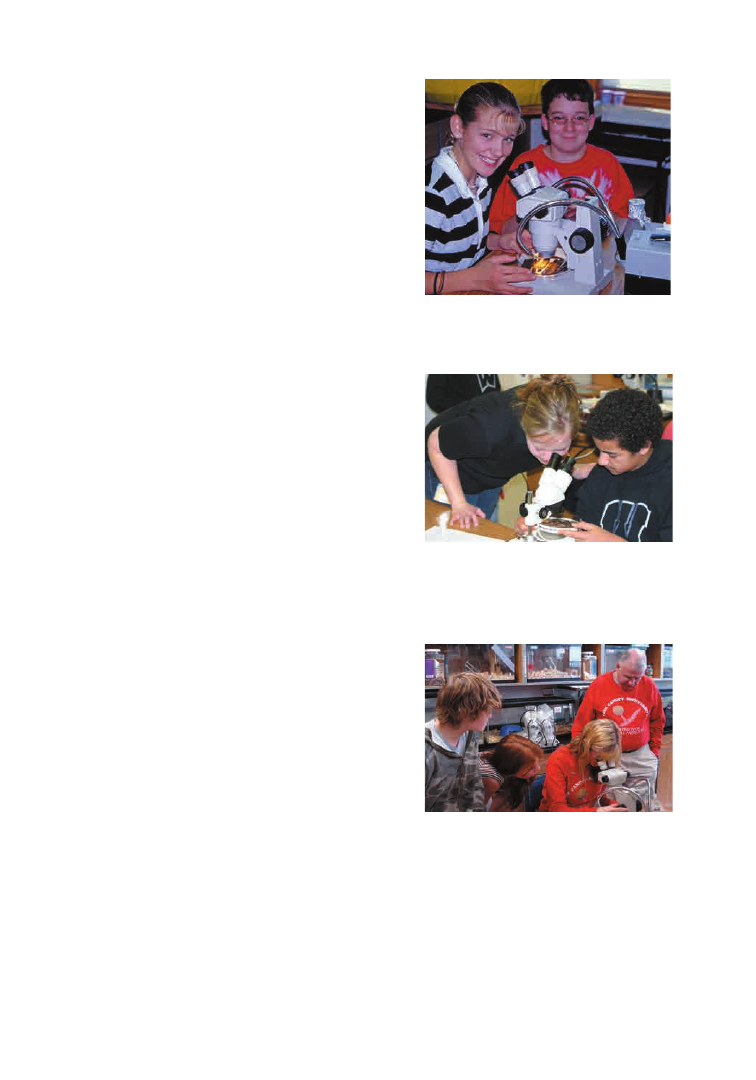

power dissecting microscopes (Figures 7–9).

Angela Scarborough (senior undergraduate

student, Figure 8) and Courtney Kilgore

(master’s degree graduate student, Figure 9)

from UCM served as mentors for the seventh-

grade students, helping them locate and

identify life forms in the moist chamber bark

cultures. They were also available to answer

questions about their tree canopy–climbing

experiences in the GSMNP.

Figure 7. Two WMS students scan moist

chamber bark cultures with dissecting

microscope. (Photo by H.W. Keller.)

Figure 8. Undergraduate UCM student Angela

Scarborough assisting WMS students search

for life forms in moist chamber bark culture.

(Photo by H.W. Keller.)

Figure 9. UCM graduate student Courtney

Kilgore scanning moist chamber cultures using

a dissecting microscope. Two WMS students

on the left, and Harold Keller on the right. Note

the red shirts worn by the UCM tree canopy

research team highlighting the iridescent

myxomycete sporangium Diachea arboricola,

a tree canopy species new to science. (Photo by

T. Smith.)

PSB 68(1) 2022

19

MOIST CHAMBER BARK

CULTURE HOW-TO VIDEO

In 2021, the first moist chamber culture

instructional video, How to Create a Moist

Chamber Culture to View the Biodiversity

Growing on Live Tree Bark, was made available

by Ashley Bordelon, Herbarium Digitization

Coordinator, of BRIT’s Urban Ecology

Program. A PDF with accompanying written

instructions is also available and can be

found at https://brit.org/research/research-

projects/urban-ecology-program/ with the

title: Preparation of Moist Chamber Tree Bark

Cultures: A Beginner's Primer for Use at Home

by Ashley Bordelon and Harold W. Keller (Fort

Worth Botanic Garden Botanical Research

Institute of Texas).

This video emphasizes the moist chamber

culture technique using live tree trunk bark

samples and store-bought low-cost supplies

readily available at local stores for teachers,

students, and hobbyists that may want to

use this technique. Many teachers cannot

afford the more expensive supplies used by

the seventh-grade students supplied by an

NSF grant–funded activity and the more

reproducible protocols required by some

publication formats. Nevertheless, this video

was created for teachers and community

enthusiasts based on live trees in their own

backyards or nearby forested areas. Examples

of myxomycete fruiting body development are

highlighted in this video. This moist chamber

technique sometimes results in the discovery

of species new to science, as well as rare

species seldom or never collected in the field

(Keller, 2004; Keller and Marshall, 2019; Perry

et al., 2020). This can be an added incentive

for beginners to share their discoveries with

other myxomycetologists, mycologists, and

botanists.

RESULTS AND

OUTREACH ACTIVITIES

Each fall for a four-year period (2004–2007),

Keller met with six different seventh-grade life

science classes (approximately 120 students)

for a total of 18 hours. More than 500 WMS

students were involved in this teaching activity

over the course of 90 hours. On September 28

and 29, 2004, six groups of 20 WMS students

were transported to Pertle Springs for one-

hour field trips to collect trunk bark samples

from living trees. During much of this time,

Angela Scarborough and Courtney Kilgore

also assisted students (Figures 8 and 9).

These activities were presented in popular

media such as newspapers, television, websites,

and exhibits. For example, UCM highlighted

our research with a color image and short

storyline on the front page of the university

website. The Daily Star Journal ran two color

images under the banner headline featuring

Local Nature Lesson, that described the

seventh-grade life science students collecting

activities at Pertle Springs, and another front-

page article titled Junior Scientists at Work,

showing a color photograph of students and

Dr. Keller observing moist chamber cultures

with a description of the RET-NSF Program.

Local interest in this RET-NSF funded project

was noted in UCM News under the title Grant

Provides Experience in Scientific Research.

Campus Today featured Trish Smith collecting

bark samples, and another article More Than

a Bug’s Life Fascinates, showed students

collecting insects using flight intercept canopy

traps at Pertle Springs. Television station

KMOS, housed at UCM, sent film crews to

shoot footage of WMS students at Pertle

Springs that aired as a five-minute segment

on University Magazine. The RET-NSF

PSB 68 (1) 2022

20

Figure 10. Tree canopy research team in GSMNP. Far left, Stan and Trish Smith; UCM

undergraduate students Amber, Tommy, Ashley back row, bottom row Erin and Cheryl; far right,

Steve Wilson. (Photo by H.W. Keller.)

poster (Keller et al., 2005) presented at the

Fifth International Congress on Systematics

and Ecology of Myxomycetes (ICSEM5) in

Tlaxcala, Mexico, was displayed at WMS and

also at the UCM Morris Science Building.

One striking example of student observations

was the surprise discovery of nematodes.

These attention-getting nematodes, with their

S-shaped wiggling and writhing movements in

thin films of water, were frequently observed

by students in moist chamber cultures from

bark of living trees. Nematodes in some bark

cultures were attached by their posterior ends,

standing and waving in a behavioral pattern

known as nictation. Nematode movements

were also observed in the video of moist

chamber bark cultures highlighted here by

Ashley Bordelon.

Our efforts to involve seventh-grade students

in the research objectives of this project was to

transfer knowledge about how biodiversity is

documented to the next generation of students.

Websites and posters also disseminated field

biology to a broader audience of students and

teachers alike (Figure 10).

CONCLUSIONS

“Teaching has been an extremely rewarding

job in many ways, but bringing the GSMNP

research project into my seventh-grade life

science classroom through the RET Program

is one of my proudest moments,” Trish

Smith said. The highest tribute or reward

Keller could ever receive is the twinkle in

the eyes and glow and smile on the faces of

the seventh-grade life science students at

WMS when they said that “it’s awesome”

or “it’s cool” after observing a myxomycete

sporangium or plasmodium. These students

learned to picture key and recognize different

myxomycete species, insect taxa, and general

life forms of lichens, mostly crustose and

foliose types. The aim of this activity was to

assist and encourage students and teachers to

experience field trips and laboratory exercises

that will create excitement and interest in

exploring, collecting, and discovering life

forms often overlooked in nature.

PSB 68(1) 2022

21

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to Trish Smith, who was

responsible for preparing the iAdventure,

Teacher Preparation Guide, Student

Worksheets, and logistics for the student field

experience at Pertle Springs and laboratory

observations. Without her and Stan’s help,

this activity would not have been possible.

Ashley Bordelon used her creative talents

to brainstorm the video content, organize

the visual images, and narrate the moist

chamber instructions. Dr. Joe Ely, ecologist

and biometrician, and Dr. Steve Wilson,

entomologist from UCM, were essential co-

investigators on this research project. Charly

Pottorff, a professional arborist, taught UCM

students the double rope climbing method and

how to shoot the Big Shot at a climbing school

at Pertle Springs. Many people contributed

their volunteer expertise and we thank them

all, including parents, faculty from the UCM

Biology and Education Departments, the

UCM student mentors and tree climbers, and

investigators from other institutions. This

student activity would not have been possible

without the help of many people not named but

who contributed time, effort, cooperation, and

authorship on publications. Multiple grants

provided financial assistance in part from the

National Science Foundation, Discover Life in

America, National Geographic Society, Sigma

Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society,

Missouri Department of Natural Resources,

the U.S. Department of Education McNair

Scholars Program, and the UCM Summer

Undergraduate Research and Creative Projects

Program. Photographic credits are given after

each photograph, and image release forms

were obtained from all WMS students. We

trust that this spirit of discovery described

here will lead others to explore, enjoy, learn,

and share their results with others.

REFERENCES

Everhart, S. E., J. S. Ely, and H. W. Keller. 2009.

Evaluation of tree canopy epiphytes and bark char-

acteristics associated with the presence of cortico-

lous myxomycetes. Botany 87: 509–517. [Techni-

cal, postgraduate level]

Gilbert, H. C, and G. W. Martin. 1933. Myxomy-

cetes found on the bark of living trees. University

of Iowa Studies in Natural History. Papers on Iowa

Fungi IV 15: 3–8. [Technical, college level]

Gilbert, H. C. 1934. Three new species of

Myxomycetes. University of Iowa Studies in

Natural History. Contributions from the Botanical

Laboratories 16: 153–159. [Technical, college level]

Keller, H. W. 2004. Tree canopy biodiversity:

student research experiences in Great Smoky

Mountains National Park. Systematics and

Geography of Plants 74: 47–65. [General audience,

non-technical]

Keller, H. W. 2005. Undergraduate Research

Field Experiences: Tree Canopy Biodiversity

in Great Smoky Mountains National Park and

Pertle Springs, Warrensburg, Missouri. Council

on Undergraduate Research Quarterly 25: 162–

168. [Invited Paper, for a non-technical, general

audience]

Keller, H. W. 2019. Student team-based tree canopy

biodiversity research in Great Smoky Mountains

National Park. Plant Science Bulletin 65: 28–37.

[General audience]

Keller, H. W. and K. L. Braun. 1999. Myxomycetes

of Ohio: Their Systematics, Biology and Use in

Teaching. Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New

Series Volume 13, Number 2. [High school and

college level]

Keller, H. W., C. M. Kilgore, S. E. Everhart, G. J.

Carmack, C. D. Crabtree, and A. R. Scarborough.

2008. Myxomycete plasmodia and fruiting bodies:

unusual occurrences and user-friendly study

techniques. Fungi 1: 24–37. [All age groups]

PSB 68 (1) 2022

22

Keller, H. W. and V. M. Marshall. 2019. A new

iridescent corticolous myxomycete species (Licea:

Liceaceae: Liceales) and crystals on American elm

tree bark in Texas, U.S.A. Journal of the Botanical

Research Institute of Texas 13: 367–386. [Technical,

for university level graduate students and teachers]

Keller, H. W., M. Skrabal, U. H. Eliasson, and

T. W. Gaither. 2004. Tree canopy biodiversity

in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park:

ecological and developmental observations of a

new myxomycete species of Diachea. Mycologia

96: 537–547. [College level]

Keller, H. W., S. W. Wilson, and P. A. Smith. 2005.

Research Experience for Teachers-National Science

Foundation: Biodiversity Survey (Myxomycetes

and Insects) of Pertle Springs, Warrensburg,

Missouri, by 7th Grade Life Science Students.

5th International Congress on Systematics and

Ecology of Myxomycetes (ICSEM5). Tlaxcala,

Mexico, Universidad Autonoma de Tlaxcala,

pp. 47–48 (Abstract, Poster Presentation #35).

[General audience]

Kilgore, C. M., H. W. Keller, and J. S. Ely. 2009.

Aerial reproductive structures on vascular plants

as a microhabitat for myxomycetes. Mycologia 101:

303–317. [Technical, college, graduate student level.

First study of myxomycetes on herbaceous prairie plants.]

Kilgore, C. M., H. W. Keller, S. E.

Everhart, A. R. Scarborough, K. L. Snell, M.

S. Skrabal, C. Pottorff, and J. S. Ely. 2008.

Research and student experiences using the

doubled rope climbing method. Journal of the

Botanical Research Institute of Texas 2: 1309–1336.

[High school and college level]

Perry, B. A., H. W. Keller, E. D. Forrester, and B. G.

Stone. 2020. A new corticolous species of Mycena

section viscipelles (Basidiomycota: Agaricales)

from the bark of a living American elm tree in

Texas, U.S.A. Journal of the Botanical Research

Institute of Texas 14: 167–185. [College Level,

Technical]

Scarborough, A. R., H. W. Keller, and J. S. Ely. 2009.

Species assemblages of tree canopy myxomycetes

related to pH. Castanea 74: 93–104. [Technical

for college students and teachers. Description of

GSMNP and Pertle Springs]

Smith, P. A. and H. W. Keller. 2004. National

Science Foundation Research Experience for

Teachers (RET). Inoculum 55: 1–5. [All age groups]

Snell, K. L. and H. W. Keller. 2003. Vertical

distribution and assemblages of corticolous

myxomycetes on five tree species in the Great

Smoky Mountains National Park. Mycologia 95:

565–576. [Technical, college level. The first tree

canopy study of cryptogams and myxomycetes using

rope-climbing techniques in the USA.]

Wilson, S. W., N. M. Svatos, and H. W. Keller.

2003. Canopy insect biodiversity in a Missouri

State Park. What’s Up? The Newsletter of the

International Canopy Network 10: 4–5. [Technical,

college level]

ADDITIONAL RELATED

PUBLICATIONS NOT CITED

Alexopoulos, C. J. and J. Koevening. 1964. Slime

molds and research. American Institute of Bio-

logical Sciences. Biological Sciences Curriculum

Studies BSCS Pamphlet 13. Boston. D.C. Heath

and Company. 36 p. [High school and college level,

targeted for teachers]

Carson, M. K. 2003. Fungi. Newbridge Education-

al Publishing. 21 pp.; see pp. 16, 17 for myxomy-

cetes. [Elementary and middle school level, part of

Ranger Rick Series]

de Hann, M. 2005. The Adventures of Mike the

Myxo. English Translation by Henry Becker. Bel-

gium KMAK. The Royal Antwerp Mycological So-

ciety. 14 p. [Elementary school level]

Keller, H. W. and T. E. Brooks. 1976. Corticolous

Myxomycetes V: Observations on the genus Echi-

nostelium. Mycologia 68: 1204–1220. [Technical,

college level]

PSB 68(1) 2022

23

Keller, H. W., and T. E. Brooks. 1977. Corticolous

Myxomycetes VII: Contribution toward a mono-

graph of Licea, five new species. Mycologia 69:

667–684. [Technical, college level]

Keller, H. W. and S. E. Everhart. 2006. Myxo

my-

ce

tes (True Slime Molds): Educational Sources for

Students and Teachers – Part I. Inoculum 57: 1–2.

and part II. Inoculum 57: 4–5. [All age groups

]

Keller, H. W. and S. E. Everhart. 2010. Importance

of Myxomycetes in biological research and

teaching. Fungi 3: 29–43. [All age groups,

targeted for teachers. This is the most cited article

on myxomycetes, first posted June 2016 on the

University of Nebraska Digital Commons and as of

February 2022 with 4,290 downloads, running at

more than 100 hits per month.]

Lloyd, S. J. 2014. Where the slime mould

creeps: the fascinating world of myxomycetes.

Tympanocryptis Press, Tasmania, Australia. 102

p. [Spectacular photography, text written for all age

groups. On pp. 40 and 41, two Slime Mould Rounds

are set to music.]

PSB 68 (1) 2022

24

By Stephen R. Stern

1,3

, Nora S. Oviatt

1,2,

, and Grace E. Gardner

1,2

1

Department of Biological Sciences, Colorado Mesa University, 1260 Kennedy Ave,

Grand Junction, CO 81501, USA

2

Undergraduate students at Colorado Mesa University that conducted the study

3

Author for correspondence: sstern@coloradomesa.edu

Abstract

Research experiences benefit undergraduates and

citizen scientists alike, and new resources allow for new

research opportunities. With the expansion of online

databases, current understanding of plant distributions

is better than it has ever been. Database resources

also show gaps in species distribution and allow rapid

identification of areas that are under-collected. Targeted

collecting of common but often overlooked plant

species is an excellent way to engage undergraduates

and citizen scientists. Here we provide an example

of targeted plant collecting by undergraduates that

resulted in 118 collections made over four days in Ouray

County, Colorado. These collections resulted in 34 new

country records not listed in the Flora of Colorado and

15 new county records not listed on SEINet.

Filling in the Gaps: Targeted Plant

Collection by Undergraduates and

Citizen Scientists to Better

Understand Plant Distribution

Key words

citizen science, Colorado, flora, species

distribution, undergraduate

Course-based Undergraduate Research

Experiences (CUREs) and outreach to the public

through citizen-science projects have become

increasingly common (AAAS, 2011; Dolan,

2016). Applications like iNaturalist have

millions of users around the globe, showing

that there is a strong interest in participating

in science (iNaturalist.org). Research can

help form beneficial collaborations between

amateurs and professionals, increase scientific

communication and engagement, and help

prepare the next generation of scientists. In

the botanical sciences, a variety of methods

has been used to engage high school students

(Ragostra et al., 2020), undergraduates (Ward

et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2017), and citizen

scientists (Boho et al., 2020).

PSB 68(1) 2022

25

One area ripe for research by amateurs

is utilizing online database resources.

Online databases, such as SEINet (www.

swbiodiversity.org) and the USDA PLANTS

database (https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/

java/), as well as traditional floras, allow

unprecedented access to plant distributions.

Mapping tools on online databases allow

users to rapidly assess plant distributions

and visualize areas that are likely habitat

for plant species but currently do not have

specimen records. Impetus for this study

began with observation of distribution maps

in the Flora of Colorado (Ackerfield, 2015)

where it was noted that Ouray County was

often a gap in species distribution maps.

Further investigation using online databases

showed that although Ouray County has been

moderately well collected compared to other

areas in western Colorado, many common

species have not been collected in this county.

Targeted collecting not only increases

understanding of species distribution, but

also benefits amateur botanists. While many

scientists use online databases, these resources

are often unknown or underutilized by the

general public. Training amateur botanists

to use online resources and technical keys,

to plan and implement a plant collecting trip,

and to process and curate specimens in the

herbarium, broadens interest in botany and

trains the next generation of botanists. Not

only are valuable data collected and made

available to scientists via databases such as

SEINet, but these studies also help to form

collaborations between scientists and plant

enthusiasts. The goals of this study were to (1)

collect specimens to fill in the gaps of species

distribution in Ouray County, Colorado, (2)

engage undergraduates in plant collecting,

and (3) provide a model for other scientists

working with undergraduate or citizen

scientists.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

This study was conducted as part of a summer

undergraduate research project led by Dr.

Stephen Stern supervising undergraduate

students Nora Oviatt and Grace Gardner. All

aspects of the project were performed by the

two undergraduate students. To become more

familiar with the area prior to collecting, the

Flora of Colorado (Ackerfield, 2015) was

used to compile a list of plants that had not

previously been collected in Ouray County.

Emphasis was given to plants that were present

in two or more neighboring counties on maps

in the Flora and therefore likely to be present in

Ouray County. The list included plant family,

common name, scientific name, elevation

range, and flowering time. This list was then

used to identify collecting sites, including

a wide range of habitats and elevations, to

maximize species diversity. Collection sites

included pinyon-juniper forests, subalpine

meadows, riparian areas, parking lots, and

other disturbed areas to include common and

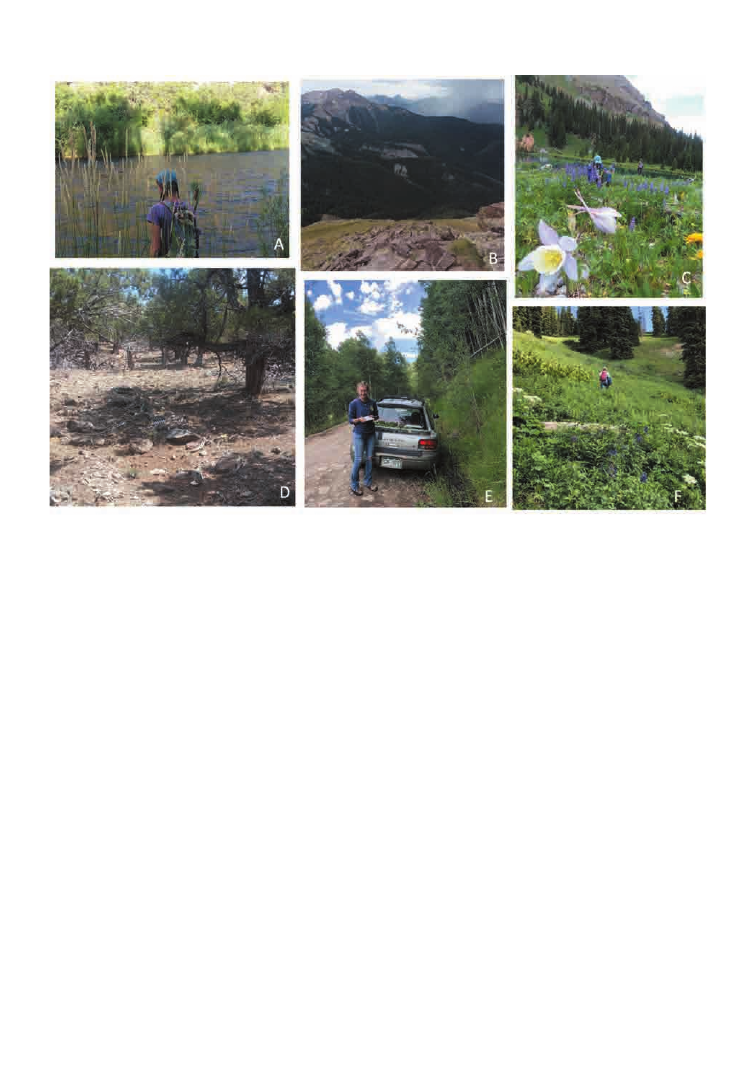

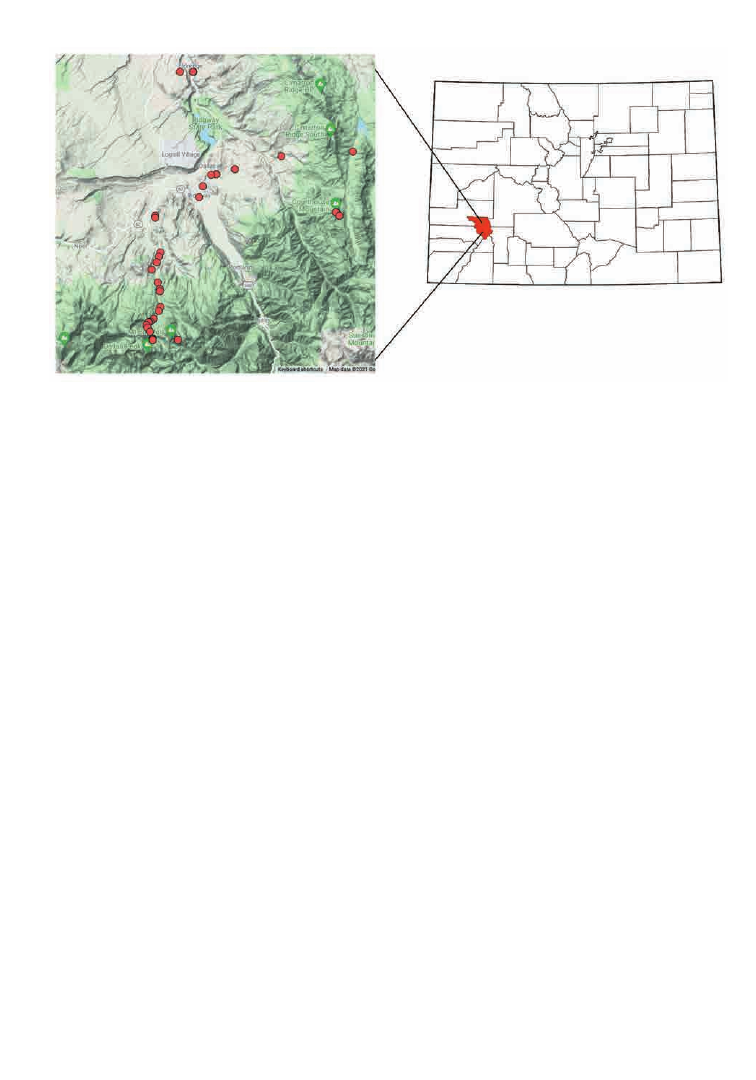

invasive species (Figure 1).

Collections were made in Ouray County,

Colorado on July 14-17, 2020 by Nora Oviatt

and Grace Gardner, two undergraduates at

Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction,

Colorado. Areas collected included a variety

of habitats, elevation ranges, and moisture

gradients (Figure 2). Plants were collected if

they were known to be missing from Ouray

County or if their identity was unknown.

Plant specimens were pressed and locality

information including GPS coordinates and

elevation was collected, along with habitat

and plant characteristic data.

PSB 68 (1) 2022

26

After collecting, the undergraduates identified

unknown plants using the Flora of Colorado

(Ackerfield, 2015). Plant specimens were

mounted onto herbarium paper with a label

including all specimen data and deposited

in the Walter A. Kelley Herbarium at

Colorado Mesa University. Specimen data

were entered in the Intermountain Region

Herbarium Network database (https://

intermountainbiota.org/portal/). Collections

were compared with distribution maps in

the Flora of Colorado (Ackerfield, 2015)

and SEINet (https://intermountainbiota.org/

portal/) to identify collections that were new

county records.

RESULTS

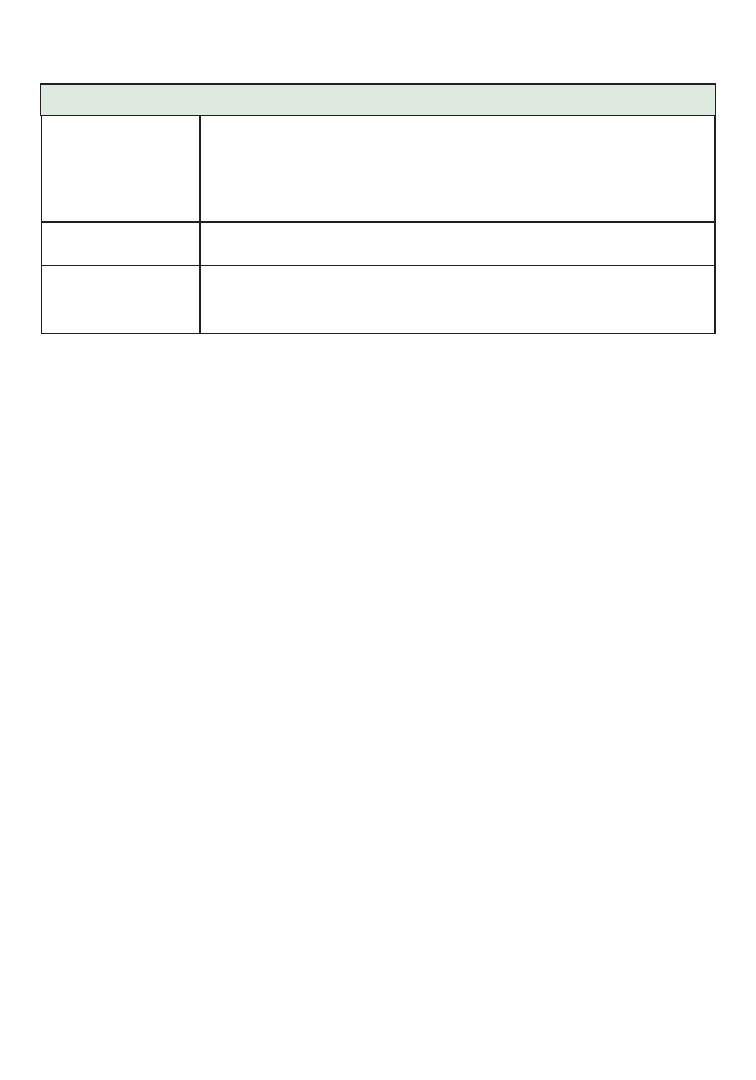

Over the course of four days of collecting in

Ouray County, 118 collections representing

99 species were made from a variety of

localities and habitats (Figures 1 and 2).

These species represent both native and

introduced, naturalized species. The goal

of this project was to provide herbarium

specimens to increase understanding of plant

distribution. Herbarium specimens collected

for this project represent 34 new county

records for Ouray County (Table 1) when

compared to distribution maps in the Flora

of Colorado (Ackerfield, 2015). Collections

Figure 1. Diversity of Habitats in Ouray County. (A) Nora Oviatt by the Uncompahgre River.

(B) Top of Courthouse Mountain. (C) Nora Oviatt in meadow by lower Blue Lake. (D) Pinyon-

Juniper habitat at the Ridgeway Area Trails. (E) Grace Gardner collecting in roadside habitat

along Ouray County Road 10. (F) Grace Gardner on Courthouse Mountain Trail.

PSB 68(1) 2022

27

were also compared with SEINet (https://

intermountainbiota.org/portal/), a regularly

updated database. Based on SEINet search

results in July 2021, the collections made in

this study represent 15 new county records for

Ouray County, Colorado (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

While much of the flora of the United States

is well-represented in herbaria, there are

significant gaps in understanding species

distributions. As the results show, a four-day

collecting trip by two undergraduates yielded

numerous new county records, indicating

that this research is beneficial in building

knowledge of species distributions. The

discrepancy in the number of new records

when comparing the distribution maps in

the Flora of Colorado versus SEINet can be

attributed to the fact that SEINet is continually

being updated. Databasing projects, such as

the NSF-funded databasing project focused

on plants of the Southern Rockies (https://

www.soroherbaria.org/portal/; Tripp et al.,

2017), have added many new records since

the publication of the Flora of Colorado.

Despite this influx of new databased records,

many areas still lack sufficient representation

by herbarium specimens.

Of the 118 collections, 34 represented

new county records based on the Flora of

Colorado and 18 represented new county

records based on SEINet (Table 1). In Ouray

County, some species were expected, such as

Convolvulus arvensis (field bindweed) that is

represented in all surrounding counties but

was lacking in Ouray County in the Flora

of Colorado distribution maps. Centaurea

stoebe (spotted knapweed) is listed as a class

B noxious weed in Ouray County (https://

ouraycountyco.gov/155/Weed-Control) but

had not previously been collected and was

not represented on SEINet or in the Flora of

Figure 2. Map of Colorado with Ouray County highlighted in red (right) with zoomed in map of

Ouray County including the towns of Ridgeway and Ouray showing collection sites (left). Red

points represent collections sites. Between 1 and 31 collections were made at each site.

Fa

mi

ly

Sci

en

tifi

c N

ame

C

ommo

n na

me

N

ew t

o

Acke

fie

ld?

N

ew t

o

SEIN

et?

C

ol

le

ct

io

n

nu

mb

er

A

m

ara

nt

hace

ae

At

rip

lex c

an

es

cens

(Pur

sh.) N

ut

t.

Fo

ur

-w

in

g Sa

ltb

us

h

ye

s

N. O

vi

at

t 73

Ap

iace

ae

Ang

eli

ca

p

in

na

ta

S. W

ats

on

Sm

al

l-w

in

g A

ng

elic

a

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 129

Ap

oc

yn

ace

ae

As

clep

ia

s s

pe

cio

sa

To

rr

.

Sh

ow

y M

ilk

w

eed

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 171

A

sterace

ae

Ca

rd

uu

s n

ut

ans

L.

M

us

k Thi

stle

ye

s

G. G

ar

dn

er 173

;

N. O

vi

att 102

A

sterace

ae

Ce

nta

ur

ea

sto

eb

e su

bsp

. m

icr

an

th

os

(S.G.G

m

elin ex. G

ug

ler) H

ay

ek

Sp

ot

ted

K

na

pw

eed

ye

s

N. O

vi

at

t 77

A

sterace

ae

Ci

ch

or

ium

in

ty

bu

s L.

C

omm

on C

hico

ry

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 179

A

sterace

ae

Er

ig

er

on

ph

ila

de

lph

icu

s v

ar

.

ph

ila

de

lph

icu

s L.

Phi

lade

lp

hi

a Fle

ab

an

e

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 112

A

sterace

ae

H

eli

an

thu

s a

nnu

us

L.

C

omm

on S

unflo

w

er

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 147

A

sterace

ae

La

ct

uc

a s

er

rio

la

L.

Pr

ic

kl

y L

et

tuce

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 168

A

sterace

ae

So

lid

ago n

em

or

al

is

su

bsp

. d

ec

emfl

or

a

(D

C.) B

ra

mm

al

l ex S

em

ple

G

ra

y G

oldenr

od

ye

s

ye

s

N. O

vi

at

t 108

A

sterace

ae

Sy

m

ph

yo

tri

ch

um

ci

lia

tum

(L

ede

b.)

G.L. N

es

om

Ra

yles

s A

lka

li A

ster

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 175

A

sterace

ae

Tet

rad

ym

ia

ca

ne

sce

ns

DC

C

om

m

on

H

or

se

br

us

h

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 111

C

on

vo

lvu

lace

ae

Con

vol

vu

lu

s a

rv

en

sis

L.

Fie

ld B

in

dw

ee

d

ye

s

N. O

vi

at

t 75

Cyp

erace

ae

Ca

rex r

ay

no

ld

sii

D

ew

ey

Ra

yn

old's S

edg

e

ye

s

ye

s

N. O

vi

at

t 113

Cyp

erace

ae

Sc

irp

us

va

lidu

s V

ahl

So

fts

tem B

ulr

us

h

ye

s

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 115

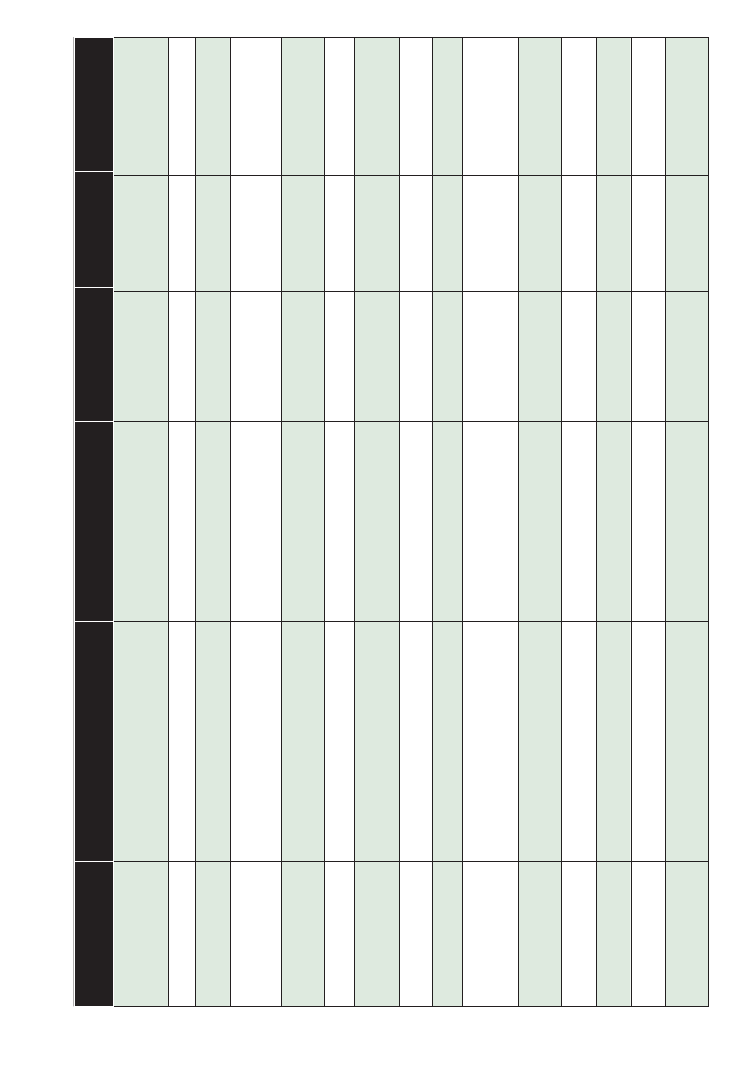

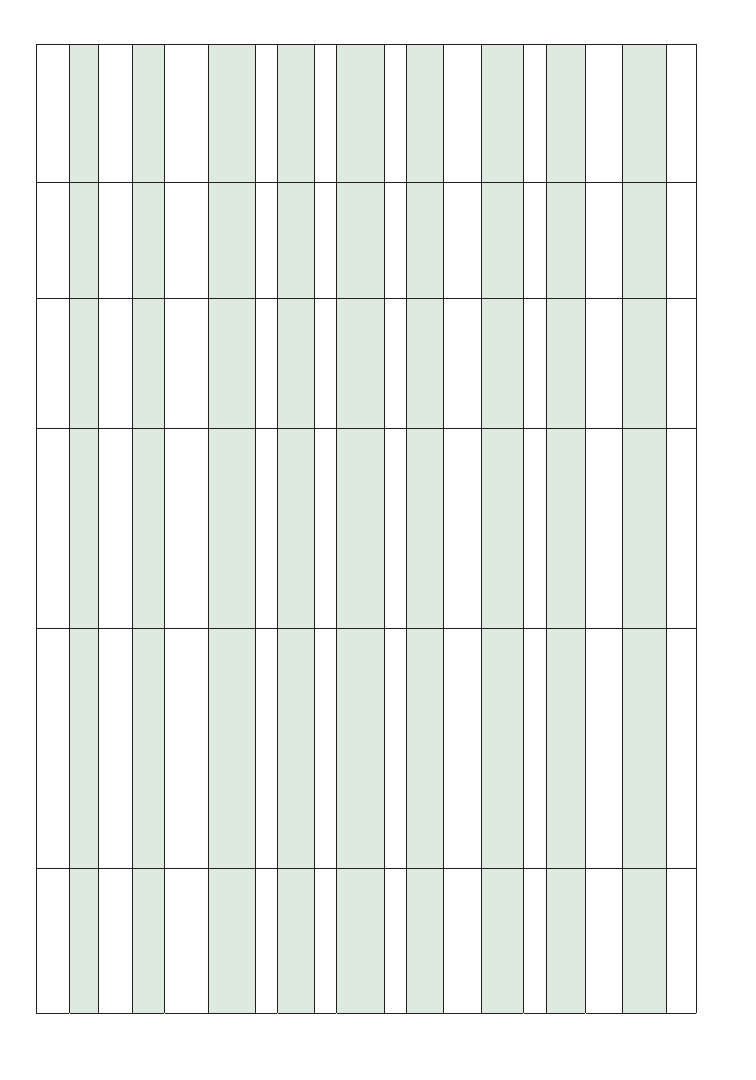

Table 1.

List of collections fr

om Ouray County that r

epr

esent new county r

ecor

ds for the Flora of Colorado (Ackerfield, 2015) and SEINet.

Fa

bace

ae

As

tra

ga

lu

s ci

cer

L.

Chic

kp

ea M

ilk

vet

ch

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 170

Fa

bace

ae

M

ed

ica

go s

at

iv

a

L.

A

lfa

lfa

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 117

Fa

bace

ae

M

eli

lo

tu

s a

lba

M

edi

k.

W

hi

te S

w

eet C

lo

ver

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 113

Fa

bace

ae

Tr

ifol

iu

m

pr

ate

ns

e L.

Re

d C

lo

ver

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 139

G

era

ni

ace

ae

Er

odium

ci

cu

ta

rium

(L.) L'H

er

. ex

A

it.

Fi

la

ria

ye

s

G. Ga

rdn

er 109

M

al