IN THIS ISSUE...

SUMMER 2021 VOLUME 67 NUMBER 2

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Cole Imperi explores the emerging

field of thanabotany... p. 101

Wanda Lovan, BSA Director of

Finance & Administration,

Retires... Inside Back Cover

Kate Parsley on new ways to combat

“plant awareness disparity”.....p. 94

Registration Now Open!

Meet the Newest Members of the BSA Board!

Vivian Negron-Ortiz

J. Chris Pires

Rachel Jabaily

Ioana Anghel

Summer 2021 Volume 67 Number 2

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 67

From the Editor

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin

Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

Seana K. Walsh

(2023)

National Tropical Botanical

Garden

Kalāheo, HI 96741

swalsh@ntbg.org

Greetings,

Summer 2021 is upon us and many of us are

still experiencing personal and professional

difficulties due to the global pandemic.

Operating conditions in many places in the

United States are slowly returning to normal

as vaccination rates have risen; however, there

is still great uncertainty as U.S. vaccinations

level off and Covid cases continue to

fluctuate globally. The second virtual Botany

conference will allow us to once again gather

in this new environment, albeit not in person.

In preparation for this meeting, we are excited

to feature many of our annual award winners

and introduce the new student representative

to the Executive Board, Ioana Anghel.

In this issue, we also present two articles that

consider the connections of people to plants.

In Dr. Kate Parsley’s article, she discusses

new strategies for describing and combatting

plant awareness disparity. I am particularly

pleased to feature this article as it furthers the

discussion on this issue that has been carried

on in the pages of Plant Science Bulletin

for several decades. Cole Imperi’s article

introduces the concept of Thanabotany and

the relationships people have with plants

in situations involving death. Recognizing

these types of relationships can only increase

people’s awareness of the importance of

plants in human culture and, hopefully, in

the environment. I hope you find these article

informative and inspiring. Sincerely,

78

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Meet the New BSA Board Members! ..................................................................................................................79

Botanical Society of America’s Award Winners (Part 1) .........................................................................80

SPECIAL FEATURES

Plant Awareness Disparity: Looking to the Past to Inform the Future .............................................94

Thanabotany: the Emerging Field Where Plants, People and Death Intersect .......................101

Poetry Corner ................................................................................................................................................................108

SCIENCE EDUCATION

PlantingScience Has Large Session, Successful Student/Scientist

Mentoring Conversations Despite Pandemic Disruptions ...................................................................112

STUDENT SECTION

Graduate School Advice .........................................................................................................................................116

Getting to Know your New Student Representative - Ioana Anghel .............................................120

MEMBERSHIP NEWS ...................................................................................................................................

122

ANNOUNCEMENTS

In Memoriam - Walter Lewis (1930–2020) .................................................................................................124

BOOK REVIEWS

............................................................................................................................................................................128

79

SOCIETY NEWS

Meet the New BSA Board Members!

Vivian Negron-Ortiz

President-Elect

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS),

Florida Ecological Services Field Office

J. Chris Pires

Secretary

University of Missouri - Columbia

Rachel Jabaily

Director-at-Large for Education

Colorado College

Ioana Anghel

Student Representative

University of California, Los Angeles

PSB 67(2) 2021

80

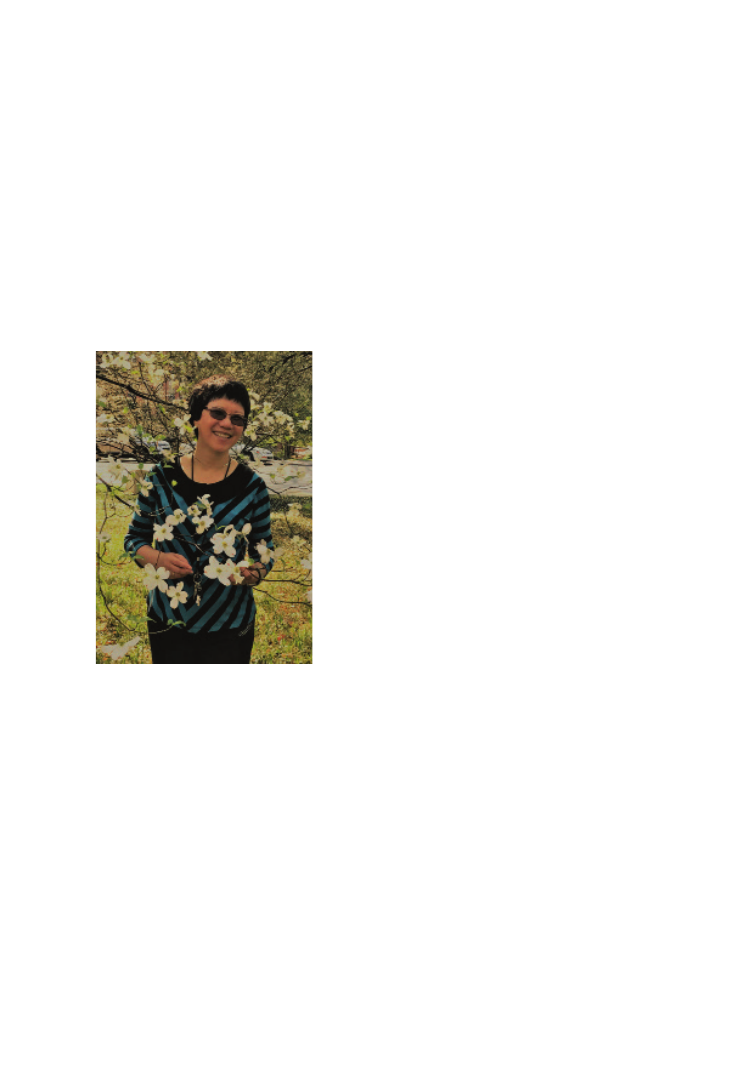

Dr. Xiang is well known globally for her

diverse contributions to plant systematics and

evolution. She is best known for her extensive

work on Cornaceae, for which she is the world’s

expert, as well as her numerous important

contributions to our understanding of the well-

known Eastern Asia–Eastern North America

floristic disjunction. Few groups of plants are

now as well-studied as dogwoods, thanks to

Jenny’s dedication. Her expertise is diverse

and spans classical taxonomy, molecular

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA’S

AWARD WINNERS (PART1)

Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America

The Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America is the highest honor our Soci-

ety bestows. Each year, the award committee solicits nominations, evaluates candidates, and

selects those to receive an award. Awardees are chosen based on their outstanding contribu-

tions to the mission of our scientific Society. The committee identifies recipients who have

demonstrated excellence in basic research, education, public policy, or who have provided

exceptional service to the professional botanical community, or who may have made contri-

butions to a combination of these categories.

DR. QIUYUN (JENNY) XIANG

North Carolina State University

systematics/phylogenetics, genomics,

and developmental genetics. Much of

her recent work focuses on population-level

and phylogeographic problems. She has an

extremely rich publication record and has

also maintained continuous NSF support

throughout her long career.

One of Dr. Xiang’s most important

contributions has been fostering close

interactions and research connectivity between

botanists in China and the United States. Since

2008, she and colleagues in China have taught

the “East Asia–North America Field Botany

and Ecology Course” at Zhejiang University

and North Carolina State University, making

a great impact on the training of Chinese

and American students in this field. This has

been a remarkable opportunity for students

from both countries and has helped to foster

new international research, as well as many

friendships. These student exchanges have

had significant impact on the number and

quality of collaborations between U.S. and

Chinese labs in the botanical sciences.

Jenny has been a life-long member of the

Botanical Society of America. She is an

outstanding mentor to students, post-docs,

and young faculty, often bringing them along

to annual scientific conferences including

PSB 67(2) 2021

81

Botany conferences. Her courses have

inspired both plant biology majors and non-

majors to think more deeply about plant

evolution and diversity. She is well respected

and well loved by her mentees, whether they are

from the United States or China or elsewhere

in the world. In addition, Jenny has been an

active reviewer for the American Journal of

Botany, served on several BSA committees, is

a frequent organizer of workshops, symposia,

special journal issues, and more—all in service

to her profession.

BSA Emerging Leader Award

Donald R. Kaplan

Memorial Lecture

This award was created to promote research

in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan

family has established an endowed fund,

administered through the Botanical Society

of America, to support the Ph.D. research of

graduate students in this area.

M. ALEJANDRA GANDOLFO-NIXON

Cornell University

DR. BRIAN ATKINSON

University of Kansas

Dr. Atkinson is currently Assistant Professor in

the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology at the University of Kansas and

curator of the paleobotany collection at the

KU Biodiversity Institute. Brian completed

his doctoral dissertation at Oregon State

University in 2017, after earning among other

awards, a NSF Doctoral Fellowship and the

BSA Paleobotanical Section Isabel Cookson

Award. Dr. Atkinson is one of the leading

scientists of his generation in paleobotany

and plant evolution. He is making impressive

contributions as a field-based scientist who

combines morphological and molecular

data, extant and extinct plants, as well as

biological and geological data. In addition,

Dr. Atkinson has become an accomplished

teacher, inspiring mentor, and an exceptional

role model.

PSB 67(2) 2021

82

BOTANY ADVOCACY LEADERSHIP GRANT

This award organized by the Environmental and Public Policy Committees of BSA and ASPT aims to

support local efforts that contribute to shaping public policy on issues relevant to plant sciences.

Rocio Deanna, University of Colorado-Boulder, for the Proposal: ARG Plant Women

Network

Karolina Heyduk, University of Hawaii, for the Proposal: Hawaiian Culture and the

Herbarium

Carolyn Mills, California Botanic Garden/Claremont Graduate University, for the Proposal

Promoting Indigenous Co-management of Federal Lands in the Nopah Range

DONALD R. KAPLAN AWARD

IN COMPARATIVE MORPHOLOGY

Donald R. Kaplan was a leading researcher in the area of plant form, where he sought to deduce fundamental

principles from comparative developmental morphology. Through his own work and the work of the many

graduate students he mentored, he had a profound effect on the fields of plant development and structure.

Kaplan always encouraged his students to work independently, often on projects unrelated to his own research.

He believed that students should publish their work independently, and rarely coauthored his students’ papers.

To promote research in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan family has established an endowed fund,

administered through the Botanical Society of America, to support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this

area. The annual award of up to $10,000 may be used to support equipment and supplies, travel for research and

to attend meetings, and for summer support. This award was created to promote research in plant comparative

morphology, the Kaplan family has established an endowed fund, administered through the Botanical Society of

America, to support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this area.

Erin Patterson, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, for the Proposal: The development and

evolution of awns in the grass subfamily Pooideae

Honorable Mention:

Jacob Suissa, Harvard University, for the Proposal: Bumps in the node: the effects of vascular

architecture on hydraulic integration in fern rhizomes

PSB 67(2) 2021

83

THE BSA GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH AWARD

INCLUDING THE J. S. KARLING AWARD

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards support graduate student research and are made on the basis of research

proposals and letters of recommendations. Withing the award group is the Karling Graduate Student Research Award.

This award was instituted by the Society in 1997 with funds derived through a generous gift from the estate of the

eminent mycologist, John Sidney Karling (1897-1994), and supports and promotes graduate student research in the

botanical sciences. The 2021 award recipients are:

THE J. S. KARLING GRADUATE

STUDENT RESEARCH AWARD

Isabela Lima Borges, Michigan State University, for the Proposal: The effects of plant inbreeding

on the legume-rhizobia mutualism

THE BSA GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH AWARDS

Laymon Ball, Louisiana State University, for the Proposal: Mutualisms, mountains, and machine

learning: Disentangling drivers of evolution in a florally diverse Neotropical plant clade, Hillieae

(Rubiaceae)

Philip Bentz, University of Georgia, for the Proposal: Origins and evolution of genetic sex-

determination and sex chromosomes in the genus Asparagus

Haley Branch, University of British Columbia, for the Proposal: Remembering the hard times:

how stress memory evolves in response to environmental pressure

Stephanie Calloway, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, for the Proposal:

Saving a rare plant species from extinction on Anacapa Island

Anri Chomentowska, Yale University, for the Proposal: Investigating the evolution of syndromes:

life history, mating system, and environmental niche of a desert-alpine lineage in the plant family

Montiaceae

Eva Colberg, University of Missouri - St. Louis, for the Proposal: The effects of prescribed fire on

ant-mediated seed dispersal of Sanguinaria canadensis

Mari Cookson, Cal State Fullerton, for the Proposal: Investigating systematics and host-parasite

coevolutionary dynamics in dwarf mistletoes (Arceuthobium spp.) using population genomics

Brandon Corder, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for the Proposal: Partial mycoheterotrophy

in North American orchids: incorporating evolutionary ecological and molecular evolutionary

approaches

PSB 67(2) 2021

84

Sontosh Deb, University of Alabama, For the Proposal: Evolution of flooding tolerance in maize

relatives

Caroline Dowling, University College Dublin, For the Proposal: The genetic architecture of

flowering time in Cannabis sativa

Samar El-Abdallah, Humboldt State University, For the Proposal: Constructing whole plant

concepts for two Early Devonian fossil plants in the assemblages of the Beartooth Butte Formation

(Wyoming)

Paige Fabre, The Ohio State University, For the Proposal: Patterns of staminode evolution in

Penstemon (Plantaginaceae)

Laura Fehling, Miami University, For the Proposal: Context-dependency of reward

complementarity in a multispecies mutualism

Emma Frawley, Washington University in St. Louis, For the Proposal: Little barley: variation,

domestication, and adaptation in a North American lost crop

Elsa Godtfredsen, Northwestern University, for the Proposal: Early snowmelt, changing

phenology and increased drought exposure: consequences for plant survival and reproduction of

four subalpine plant species

Nikolai Hay, Duke University, for the Proposal: Locating a “missing link” using microsatellite

data from herbarium specimens

Zhe He, Harvard University, for the Proposal: Pit membranes and plant resistance to cavitation

Samuel Lockhart, Ohio University, for the Proposal: Population genetic structure and breeding

system characterization of four mixed-breeding violets and one exclusively chasmogamous violet

Diana Macias, University of New Mexico, for the Proposal: Adaptability of piñon pine (Pinus

edulis) populations to future hot droughts

Janet Mansaray, Louisiana State University, for the Proposal: Plants, ants, and curvy bills: the

evolution of mutualisms in neotropical bellflowers

Skylar McDaniel, Utah State University,for the Proposal: Floral microbiome assembly and

function in the face of phenological change

Michael McKibben, University of Arizona, for the Proposal: The Contribution of paleopolyploidy

to adaptation in diploid descendants

PSB 67(2) 2021

85

Elise Miller, University of Minnesota Duluth, for the Proposal: How do sources, sinks, and

physical constraints impact phloem hydraulic conductivity?

Carina Motta, Universidade Estadual Paulista – Rio Claro, for the Proposal: Contribution of a

naturalized tropical tree to bird diet in secondary forest fragments

Taryn Mueller, University of Minnesota, for the Proposal: Ecological genetic drivers of foliar

fungal endophyte community assembly in Clarkia xantiana

Olivia Murrell, Northwestern University, for the Proposal: Influence of metapopulation dynamics

on genetic structure: Case study of the endangered and exceptional species Amorphophallus

titanium

Deannah Neupert, Miami University, for the Proposal: The evolution and development of the

aerial bulbil: a study of novelty in Mimulus

Megan Nibbelink, Humboldt State University,

for the Proposal: Anatomically-preserved

zosterophylls of the Battery Point Formation (Québec, Canada) and a new analysis of zosterophyll

relationships

Kasey Pham, University of Florida, for the Proposal: What got swapped? Investigating the

genomic consequences of hybridization in two species of Eucalyptus

Alyssa Phillips, UC Davis, for the Proposal: Origins of polyploidy and their impact on adaptation

in Andropogon gerardi

Neill Prohaska, University of Arizona, for the Proposal: How does leaf microclimate affect

population density and diversity of microbes living on leaves in tropical forest canopies?

Austin Rosen, Colorado State University, for the Proposal: Uncovering taxonomic boundaries

in a group of seep-loving desert thistles (Asteraceae: Cirsium)

Malia Santos, University of Idaho, for the Proposal: Investigating species relationships and

evolutionary patterns of defense strategies in Tricalysia (Rubiaceae)

Amber Stanley, University of Pittsburgh, for the Proposal: Have floral traits of Impatiens

capensis responded to pollinator mismatches caused by climate change and urbanization? A

retrospective study using herbarium specimens

Christina Steinecke, Queen’s University, for the Proposal: Investigating correlated evolution of

sexual and asexual reproduction in Mimulus guttatus

Andrea Turcu, The University of Louisiana at Lafayette, for the Proposal: The evolution of

divergent mating systems across temporally and spatially heterogeneous environments

PSB 67(2) 2021

86

Emma Vtipilthorpe, North Carolina State University, for the Proposal: Relationships between

niche breadth and geographic range size in Liatris

Sophie Young, Lancaster University, for the Proposal: Phloem loading in the context of C4

photosynthesis in tree-form Hawaiian Euphorbia

Joseph Zailaa, Yale University, for the Proposal: Investigating drought impacts on native-

California shrubland vegetation from cells to communities

THE BSA UNDERGRADUATE

STUDENT RESEARCH AWARD

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards support undergraduate student research and are

made on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendation.

Anais Barnes, Bucknell University, for the Proposal: Assessing the geographic distribution and

conservation status of Heuchera alba and Heuchera pubescens using field surveys, morphology and

genomics methods

Jeffrey Heim, Bucknell University, for the Proposal: A population genomics approach to under-

standing the role of Indigenous foragers in the distribution and genetic diversity of an Australian wild

bush tomato (Solanum diversiflorum)

Matthew Hilz, Saint Louis University, for the Proposal: Testing the effect of plant age on phenotypic

traits in the field

Hsin Kuo, National Taiwan University, for the Proposal: Evolution of the AUXIN RESPONSE FAC-

TOR gene family in land plants

Claire Marino, Bucknell University, for the Proposal: Solanum sp. ‘Deaf Adder,’ a new bush tomato

species from the Australian monsoon tropics

Theodore Matel, Cornell University, for the Proposal: Cunoniaceae fossil from the early Eocene

(~58 m. y.) Laguna del Hunco, Huitrera Formation, Patagonia, Argentina

Ryan McGinnis, Drake University, for the Proposal: Battle of the sexes: Intra- and Interindividual

floral variation in a native fruit tree, American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana, Ebenaceae)

Nola Rettenmaier, Cornell University, for the Proposal: Assessing NAM/CUC3 Expression in Costus

spicatus

Nicholas Rocha, Cornell University, for the Proposal: The role of pollinators in the phenotypic diver-

sity of Calochortus venustus

Aryaman Saksena, Cornell University, for the Proposal: Evolution of floral fusion in the banana

families

Emily Smith, Drake University, for the Proposal: The function of staminodes in the reproductive suc-

cess and pollination ecology of American Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana (Ebenaceae)

Ethan Stolen, University of Florida, for the Proposal: The impact of genome doubling on gene ex-

pression noise in Arabidopsis thaliana

PSB 67(2) 2021

87

THE BSA YOUNG BOTANIST AWARDS

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual recognition to outstanding graduating seniors in

the plant sciences and to encourage their participation in the Botanical Society of America.

Andrea Appleton, Georgia Southern University, Advisor: Dr. John Schenk

Olyvia Foster, University of Guelph, Advisor: Dr. Christina Caruso

Renée Geyer, Oberlin College, Advisor: Dr. Michael J. Moore

Jonathan Hayes, Bucknell University, Advisor: Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Jeff Heim, Bucknell University, Advisor: Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Emily Humphreys, Oberlin College, Advisor: Dr. Michael J. Moore

Kiana Lee, University of Guelph, Advisor: Dr. Christina Caruso

Michelle Liu, Oberlin College, Advisor: Dr. Michael J. Moore

Tallia Maglione, Connecticut College, Advisor: Dr. Rachel Spicer

Jordan Manchego, University of Alabama-Huntsville, Advisor: Dr. Alex Harkess

Livia Martinez, Barnard College - Columbia University, Advisor: Dr. Hilary Callahan

Colleen Mills, Weber State University, Advisor: Dr. Sue Harley

Abigail Moore, Ohio University, Advisor: Dr. John Schenk

Claire Pellegrini, Connecticut College, Advisor: Dr. Rachel Spicer

Eva Popp, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Advisor: Dr. Steven Handel

Riki Ross, University of Akron, Advisor: Dr. Randall Mitchell

Megan Soehnlen, Walsh University, Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Clevinger

Heather Wetreich, Bucknell University, Advisor: Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Shefka Williams, Connecticut College, Advisor: Dr. Rachel Spicer

PSB 67(2) 2021

88

THE BSA PLANTS GRANT RECIPIENTS

The PLANTS (Preparing Leaders and Nurturing Tomorrow’s Scientists: Increasing the diversity of

plant scientists) program recognizes outstanding undergraduates from diverse backgrounds and pro-

vides travel grant.

Anais Barnes, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

Serena Blais, California State University, Sacramento, Advisor: Clayton Visger

Jonathan Carcache, Florida International University, Advisor: Daniela Hernandez

Josh Felton, Colorado College, Advisor: Rachel Jabaily

Aaliyah Holliday, Cornell University, Advisor: Chelsea D. Specht

Caitlyn Hughes, University of Georgia, Advisor: Jim Leebens-Mack

Emily Hughes, Rutgers University, Advisor: Suzanne Sukhdeo

Al Lichamer, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Advisor: Ingrid Jordon-Thaden

Annie Nelson, University of Nebraska- Lincoln, Advisor: Katarzyna Glowacka

Matthew Norman, Atlanta Botanical Garden, Advisor: Lauren Eserman

Deirdre O’Malley, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Advisor: Shannon Straub

Ryan Schmidt, Rutgers University, Advisor: Lena Struwe

Madilyn Vetter, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire, Advisor: Nora Mitchel

Jayla Wade, Howard University, Advisor: Dr. Janelle Burke

Audrey Widmier, Mercer University, Advisor: Dr. John Stanga

THE BSA DEVELOPING NATIONS TRAVEL GRANTS

Yetunde Bulu, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Nigeria

Paula Burchardt, Londrina State University (UEL), Brazil

Laura Calvillo Canadell, Instituto de Biología, UNAM., Mexico

PSB 67(2) 2021

89

Ítalo Coutinho, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Brazil

Kelsey Glennon, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Thliza Ijai Ayuba, Federal University, Gashua, Yobe State, Nigeria

Yesenia Madrigal, Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia

Oluwasanmi Odeyemi, Federal College of Animal Health and Production Technology, Nigeria

Oluwatobi OSO, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Vashist N. Pandey, DDU Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, India

Nantenaina Herizo Rakotomalala, Kew Madagascar Conservation Centre, Madagascar

THE BSA STUDENT AND POSTDOC TRAVEL AWARDS

Winners were selected by lottery

Diana Castillo Diaz

Paige Ellestad

Chuangwei Fang

Matias Köhler

Jessica LaBella

Francesco Martini

SOUTHEASTERN SECTION STUDENT

PRESENTATION AWARDS

The following winners were selected from the Association of Southeastern Biologists meeting that took place at the end

of March, 2021.

Southeastern Section Paper Presentation Award

Emily Oppmann, Middle Tennessee State University

Funmilola Mabel Ojo

Namrata Pradhan

Laura Super

Yingtong Wu

Mei Yang

PSB 67(2) 2021

90

Southeastern Section Poster Presentation Award

Regina Javier, Appalachian State University

ECOLOGICAL SECTION STUDENT TRAVEL AWARDS

Mimi Serrano, San Francisco State University, Advisor: Dr. Kevin Simonin, for the

Presentation: Tracking Leaf Trait Differentiation of Newly Diverging Subspecies of Chenopodium

oahuense on the Hawaiian Islands

Laura Super, University of British Columbia, Advisor: Dr. Robert Guy, for the Presentation: The

impact of simulated climate change and nitrogen deposition on conifer phytobiomes and associated

vegetation Co-author: Dr. Robert Guy

Yingtong Wu, University of Missouri - St. Louis, Advisor: Dr. Robert E. Ricklefs, for the

Presentation: What Limits Species Ranges? Investigating the Effects of Biotic and Abiotic Factors

on Oaks (Quercus spp.) through Experiments and Field Survey Co-author: Dr. Robert E. Ricklefs

PTERIDOLOGICAL SECTION & AMERICAN FERN

SOCIETY STUDENT TRAVEL AWARDS

Ana Gabriela Martinez Becerril, National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM. Faculty

of Higher Studies Zaragoza, Advisor: Alejandra Vasco, for the Proposal: Disentangling the

systematics of the Elaphoglossum petiolatum complex (Dryopteridaceae) Co-author: Alejandra Vasco

PSB 67(2) 2021

91

PSB 67(2) 2021

92

PSB 67(2) 2021

93

Botany 2021 and Plant Biology 2021

Present a Special Joint Symposium

Wednesday July 21, 11:00 am (ET)

Symbiotic forms and the

lichenized phenotype

Klara Scharnagl

University of California, Berkeley

Heather Hallen-Adams

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Mycological Society of America

Elizabeth Kellogg

The Danforth Center

Botanical Society of America

Gary Stacey

University of Missouri

American Society of

Plant Biologists

Bacterial endosymbionts of

Mucoromycota fungi;

lessons from evolutionary,

functional, and

computational genomics

Jessie Uehling

Oregon State University

Perception of

lipo-chitooligosaccharides

by the bioenergy crop

Populus

Jean-Michel Ané

University of Wisconsin

Bidirectional communication

along the

microbiome-root-shoot axis.

Corné Pieterse

Utrecht University

A set of conserved receptors

is essential for root system ar-

chitectural changes induced by

arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Uta Paszkowski

Cambridge University

Organized by:

An Exploration of

Inter-kingdom Interactions

Featuring:

94

SPECIAL FEATURES

A SHORT HISTORY OF

PLANT BLINDNESS

Many readers of the the Plant Science Bulletin

are likely familiar with a problem that has

plagued botanists and science educators for at

least a century: most students are not interested

in learning about plants. This simple fact has

been written about extensively, both within

this very publication and throughout the field

of botany education research (e.g., Balas and

Momsen, 2014; Hershey, 2002; Strgar, 2007;

Wandersee, 1986; Wandersee et al., 2006;

Wandersee and Schussler, 1999; Wandersee

and Schussler, 2001).

Plant Awareness Disparity: Looking

to the Past to Inform the Future

By Kathryn M. Parsley

Education Project

Manager

Education Research and

Outreach Laboratory

Donald Danforth Plant

Science Center

What many people do not often recognize

is that the history of this problem is more

extensive than it seems on the surface. The

original idea behind plant blindness first

surfaced in the journal Science in 1919, when

George Nichols discussed the teaching of

botany and zoology in American universities

and how the development of general biology

courses would affect these topics. In the

article, Nichols laments that these new general

biology courses “are responsible for the

popular delusion that biology is the study of

animals: that the words biology and zoology

are synonymous,” (Nichols, 1919). Before

this phenomenon even had a name, plant

blindness was recognized as a major problem

for biology education.

Several years later, in 1994, the term

“zoochauvinism” appeared on the scene.

Zoochauvinism is known as a bias against

plants in favor of animals, and while this

term appeared first in the literature, it is now

largely recognized as a consequence of plant

blindness (Bozniak, 1994; Hershey, 1993;

Wandersee and Schussler, 2001). Shortly

after, the term “plant blindness” was coined

by James Wandersee and Elisabeth Schussler

(Wandersee and Schussler, 1999, 2001).

Email: kparsley@danforthcenter.org

Twitter and Instagram @KathrynMParsley

Website: www.kathrynmparsley.com

Blog: https://plantawarenessdisparity.word-

press.com/

PSB 67(2) 2021

95

Plant blindness is defined as “the inability

to see or notice the plants in one’s own

environment—leading to: (a) the inability

to recognize the importance of plants in

the biosphere, and in human affairs; (b)

the inability to appreciate the aesthetic and

unique biological features of the life forms

belonging to the Plant Kingdom; and (c)

the misguided, anthropocentric ranking of

plants as inferior to animals, leading to the

erroneous conclusion that they are unworthy

of human consideration,” (Wandersee and

Schussler, 2001). This definition can be

extrapolated into four components of plant

blindness: attention, attitude, knowledge, and

relative interest (Parsley, 2020). The attention

component refers to the visual phenomenon of

not noticing plants in an environment, which

is supported by research in visual cognition

(Balas and Momsen, 2014; Norretranders,

1998; Parsley, 2020). The attitude component

is denoted by a lack of positive affect toward

plants and/or being apathetic toward them

(Parsley, 2020; Parsley et al., in review). The

knowledge component refers to the inability

to recognize the importance of plants in

the biosphere and human affairs (Parsley,

2020; Uno, 2009; Wandersee and Schussler,

2001). The relative interest component is

characterized by a lack of interest in plants

when compared to animals (Lindemann‐

Matthies, 2005; Parsley, 2020; Wandersee,

1986; Wandersee and Schussler, 2001).

These four components and the detailed

definition of plant blindness indicate that

this phenomenon goes much further than

simply not noticing plants. These attentional

deficits cascade into impacts on student

attitude, interest, and knowledge, and each

is an important component to student

learning. This makes plant blindness a multi-

faceted, complex problem that has significant

implications for biology and botany education.

As such, what we call the phenomenon and

the language we use to describe it matters. In

the past few years, botanists and educators

have spoken out about the problems with the

term plant blindness and how it is inherently

exclusive toward disabled scientists. For

example, McDonough MacKenzie

et al. (2019)

posited that instead of focusing on “curing

plant blindness,” we should instead seek to

“grow plant love.” While the ideas behind the

term are not in question (no one is proposing

to change the definition cited above), the term

itself has been identified as a potential barrier

to diversity and inclusion within the plant

sciences.

MOVING AWAY FROM

THE TERM

“PLANT BLINDNESS”—

WELCOMING DIVERSITY,

ACCESSIBILITY, AND

INCLUSION

Although the term plant blindness is unique

in that it captures an incredibly complex

phenomenon in a simple and easily digestible

phrase, it is still highly problematic in other

ways. The authors who developed this term

used a disability metaphor, and while ableism

was not the authors’ intention, disability

metaphors are inherently ableist (McDonough

MacKenzie et al., 2019; Sanders, 2019).

Disability metaphors equate disabilities with

negative or undesirable traits that require

“fixing” (Schalk, 2013; Smith, 2015). As

someone who is visually impaired and has

learning disabilities, I must admit that I do find

it problematic to equate blindness with not

noticing plants in my environment. If we are to

PSB 67 (2) 2021

96

promote a diverse and equitable environment

in which everyone feels comfortable learning

about plants, it is important that we choose

language to reflect these goals.

As such, I have proposed that we change

the term plant blindness to a new one: plant

awareness disparity (PAD) (Parsley, 2020).

Plant awareness disparity is accurate,

inclusive, and maintains the conceptual

intentions behind the original term. PAD

highlights the fact that the root of the problem

with this phenomenon is a disparity in visual

attention between plants and animals. The

problem is not just that we do not see plants,

it is that our visual systems have evolved to

place plants in the background of our visual

field in service of noticing animals (Parsley,

2020). At the same time, it recognizes that this

visual cognition reality creates the other three

components of PAD. This attention disparity

between plants and animals is responsible for

the development of negative attitudes toward

plants, a lack of interest in plants, and a lack

of knowledge of why plants are important

(Parsley, 2020). As such, PAD emphasizes

the visual roots of the phenomenon while

still encompassing the rest of the original

definition of plant blindness. Because PAD is

both more inclusive and continues to preserve

the integrity of the definition behind plant

blindness, I have begun using PAD to refer to

this phenomenon instead of plant blindness.

I encourage others to do the same for the

reasons outlined above.

PAD IN EDUCATIONAL

SYSTEMS AND TOOLS

PAD is present at all levels of education and

can even be transmitted from teachers to

students. For example, Nyberg et al. (2019)

noted that elementary school student teachers

notice plants in environments where plants

are in the foreground (such as botanical

gardens), much more than in environments

where animals are the focus (such as a science

center). These findings regarding student

teachers are significant, because if student

teachers do not have experiences with plants

in the foreground, their PAD levels may

continue uninhibited until they begin teaching

students. Once they do, these new teachers

may favor animals in biology examples,

leading to PAD in their students as well. There

is even evidence that high school students do

not perceive plants as being alive, partly due

to plants’ lack of observable motion (Yorek et

al., 2009). PAD does not automatically decline

over time without an intentional intervention.

Examples of intentional interventions include:

educational curriculum, the introduction of a

plant mentor (someone who mentors others

and teaches them about the importance of

plants), or the special interest and enthusiasm

of a teacher.

PAD is even a problem within the very

instructional tools that we use to teach

biology. Schussler et al. (2010) discovered that

even in two nationally syndicated textbook

series in the United States, animals and

plants are represented unequally. There were

more than twice as many animal examples

as plant examples in the textbooks. Even in

highly regarded and frequently used general

biology textbooks at the university level, this

trend continues. Brownlee et al. (2021) noted

a similar tendency for textbooks to represent

animals in images more often than plants

(and focus on animals in images containing

both plants and animals). PAD is infused into

instructional materials at all educational levels

in the United States. As one might imagine,

this has disastrous consequences for botanical

PSB 67(2) 2021

97

literacy and botany education. If students

are not exposed to both plant and animal

examples of biological concepts, they can

come away with misconceptions such as that

plants do not evolve.

HOW TO COMBAT PAD

IN AND OUTSIDE OF THE

CLASSROOM

Given how ubiquitous PAD is at all levels of

education (particularly in the United States),

many authors have explored strategies to

reduce PAD in a multitude of contexts.

Wandersee et al. (2006) probed community

college students’ botanical sense of place to

help them see and understand how plants are

important to not only the students, but also

humans in general. Frisch et al. (2010) used

this approach to help educate science teachers

about why teaching plants in elementary

school is important as well.

A proposed way to alleviate PAD in K-12

students is through an outdoor education

program, where students (ages 10 and 11)

have hands-on opportunities to interact with

the plants (Fančovičová and Prokop, 2011).

Wyner and Doherty (2019) demonstrated

that local street trees can be used to decrease

urban middle school students’ levels of PAD,

despite a lack of large outdoor spaces present

in these urban environments. Patrick and

Tunnicliffe (2011) demonstrated that children

of the ages 4, 6, 8, and 10 are in touch with

their environment to varying extents, and that

children who have rich experiences outdoors

tend to have more knowledge about both

plants and animals.

Outside of formal learning environments,

Hoekstra (2000) noted that in order to help

combat PAD, botanists should partner with the

media and get better at presenting information

in a relatable and entertaining way. Hershey

(2002) had several ideas for combating PAD:

a college course for preservice teachers, an

online botanical glossary, a botanical seal of

approval on biology textbooks from botanists,

and even a bibliography of accurate botanical

and biological teaching materials. Wandersee

and Schussler (2001) noted that having a

knowledgeable and friendly plant mentor has

also been shown to result in lowered PAD

in students. Having experiences with a plant

mentor also results in increased attention to,

interest in, and scientific understanding of

plants at a later point in life for many people.

Wandersee and Schussler took an activist

approach in their 1999 paper, in which

they announced that they were launching a

campaign to “prevent plant blindness,” as it

was then called, which was followed up with

special posters to hang in classrooms and

even a children’s book about a plant. To follow

up with this idea, they even created an award

called the Giverny Award for children’s books

that accurately teach at least one scientific

principle, and preference is given to books

that teach about botany and plant biology.

NEW STRATEGIES AND

SUGGESTIONS FOR

APPROACHING PAD

In the Classroom

Parsley et al. (in review) note that when

designing ways to reduce PAD in students, it

is important to consider that simply teaching

students may not be enough. We found

that even after an active learning botanical

PSB 67 (2) 2021

98

curriculum, only student attention and

knowledge of plants improved significantly—

their attitudes and interest in plants did not

(Parsley et al., in review). This is important

because if we are to reduce PAD, we have to

be sure to address the problem from a more

holistic perspective. Botanists and instructors

cannot rely on increased knowledge alone to

change students’ minds about plants.

Introductory biology textbooks need to

improve their representation of plants in

images at both the elementary and university

levels (Schussler et al., 2010; Brownlee et al.,

2021). Instructors who are using textbooks

with high levels of PAD should incorporate

outside resources such as herbarium

specimens, online repositories such as

botanydepot.com, and even botanical social

media accounts to better represent plants in

their classes (Brownlee et al., 2021).

In Personal Experiences

Making plants personal seems to be a major

strategy to help combat PAD. Krosnick et

al. (2018) noted that personal experience

growing plants and treating them as pets can

also have an effect on PAD. When students get

personally invested in these activities, it can

help them develop those feelings of empathy

that also develop when they have a plant

mentor or have significant memories of being

around plants in their childhood.

Notably, my research (both in exploring

the literature and in conducting my own

research studies) indicates that interpersonal

relationships are an important part of reducing

PAD. Often the relationship with a plant

mentor, family member, or friend is what gets

students interested in plants. It typically takes

students being taught by another person how

to empathize with plants, while this seems to

happen automatically with animals.

As instructors, botanists, and outreach

activists, we can take on this role for our

students. We can go the extra mile to

demonstrate our enthusiasm for plants, and to

encourage the same in our students. And, if

we are ever going to be rid of PAD, we must do

these things. To advance in the fight against

PAD and botanical illiteracy, I am proposing a

social media campaign specific to PAD.

Online

On Twitter or Instagram, use #PADisBad

to tell the world how you are fighting PAD

with educational curricula, field trips,

active learning activities, or even science

communication methods. If you have funny

memes related to PAD, ideas for interventions

to reduce PAD, or if you just want to show

others how PAD affects their lives, #PADisBad

can help get the word out. The more people

involved in this discussion, the more likely we

are to make a difference in PAD and botanical

literacy, not only for our students, but also for

the public at large.

LITERATURE CITED

Balas, B., and J. L. Momsen. 2014. Attention “blinks”

differently for plants and animals. CBE-Life Sciences

Education 13: 437-443.

Bozniak, E. C. 1994. Challenges facing plant biology

teaching programs. Plant Science Bulletin 40: 42–46.

Brownlee, K., K. M. Parsley, and J. L. Sabel. 2021. An

analysis of plant awareness disparity within introduc-

tory biology textbook images. Journal of Biological

Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2021.19

20301

Fančovičová, J., and P. Prokop. 2011. Plants have a

chance: outdoor educational programmes alter stu-

dents’ knowledge and attitudes towards plants. Envi-

ronmental Education Research 17: 537-551.

PSB 67(2) 2021

99

Frisch, J. K., M. M. Unwin, and G. W. Saunders. 2010.

Name that plant! Overcoming plant blindness and de-

veloping a sense of place using science and environ-

mental education. In The inclusion of environmental

education in science teacher education (pp. 143-157).

Springer, Dordrecht.

Hershey, D. R. 1993. Plant neglect in biology educa-

tion. BioScience 43: 418-418.

Hershey, D. R. 2002. Plant blindness: “I have met the

enemy and he is us”. Plant Science Bulletin 48: 78-84.

Hoekstra, B. 2000. Plant blindness: The ultimate chal-

lenge to botanists. The American Biology Teacher 62:

82-83.

Krosnick, S. E., J. C. Baker and K. R. Moore. 2018.

The pet plant project: Treating plant blindness by mak-

ing plants personal. The American Biology Teacher 80:

339-345.

Lindemann-Matthies, P. 2005. ‘Loveable’ mammals

and ‘lifeless’ plants: how children’s interest in common

local organisms can be enhanced through observation

of nature. International Journal of Science Education

27: 655-677.

McDonough MacKenzie, C., S. Kuebbing, R. S. Barak,

M. Bletz, J. Dudney, B. M. McGill, M. A. Nocco et

al. 2019. We do not want to “cure plant blindness”

we want to grow plant love. Plants, People, Planet 1:

139–141.

Nichols, G. E. 1919. The general biology course and the

teaching of elementary botany and zoology in Ameri-

can colleges and universities. Science 50: 509–517.

Norretranders, T. 1998. The user illusion. New York

Viking.

Nyberg, E., A. M. Hipkiss, and D. Sanders. 2019.

Plants to the fore: Noticing plants in designed environ-

ments. Plants, People, Planet 1: 212-220.

Parsley, K. M. B. J. Daigle, and J. L. Sabel. (in review).

Development and validation of the plant awareness

disparity index to assess undergraduate levels of plant

awareness disparity. CBE—Life Sciences Education.

Parsley, K. M. 2020. Plant awareness disparity: A case

for renaming plant blindness. Plants, People, Planet 2:

598-601.

Patrick, P., and S. D. Tunnicliffe. 2011. What plants

and animals do early childhood and primary students’

name? Where do they see them? Journal of Science

Education and Technology 20: 630-642.

Sanders, D. L. 2019. Standing in the shadows of plants.

Plants, People, Planet 1: 130–138.

Schalk, S. 2013. Metaphorically speaking: Ableist

metaphors in feminist writing. Disability Studies Quar-

terly 33(4) https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3874/3410.

Schussler, E. E., M. A. Link-Pérez, K. M. Weber, and

V. H. Dollo. 2010. Exploring plant and animal content

in elementary science textbooks. Journal of Biological

Education 44: 123-128.

Smith, S. E. 2015. Disability as a metaphor, and why

you shouldn’t. this ain’t livin’ [blog post] Website:

http://meloukhia.net/2015/05/disability_as_metaphor_

and_why_you_shouldnt/.

Strgar, J. 2007. Increasing the interest of students in

plants. Journal of Biological Education 42: 19-23.

Uno, G. E. 2009. Botanical literacy: What and how

should students learn about plants? American Journal

of Botany 96: 1753-1759.

Wandersee, J. H. 1986. Plants or animals—which do

junior high school students prefer to study? Journal of

Research in Science Teaching 23: 415-426.

Wandersee, J. H., R. M. Clary, and S. M. Guzman.

2006. A writing template for probing students’ botani-

cal sense of place. The American Biology Teacher 68:

419-422.

Wandersee, J. H., and E. E. Schussler. 1999. Prevent-

ing plant blindness. The American Biology Teacher 61:

82-86.

Wandersee, J. H., and E. E. Schussler, E. E. 2001. To-

ward a theory of plant blindness. Plant Science Bul-

letin 47: 2-9.

Wyner, Y., and J. H. Doherty. 2019. Seeing the trees:

what urban middle school students notice about the

street trees that surround them. Journal of Biological

Education 55: 1-23.

Yorek, N., M. Şahin, and H. Aydın. 2009. Are animals

‘more alive’ than plants? Animistic-anthropocentric

construction of life concept. Eurasia Journal of Mathe-

matics, Science and Technology Education 5: 369-378.

PSB 67 (2) 2021

100

FROM THE

PSB

ARCHIVES

60 years ago

A condensation of papers given at the Teaching Section Symposium “The Botanical Garden as an

Outdoor Teaching Laboratory” are published, including articles by Walter Hodge, William Campbell

Steere, and William S. Stewart.

--PSB 7(2): 4-6.

50 years ago

“Owing to increasing costs and decreasing revenues, Dr. Lawrence J. Crockett, Business Manager,

American Journal of Botany, regrets to announce that the very liberal rule that everybody who pub-

lishes in the journal receives the first 100 reprints free must be changed. Beginning with the August

issue, only those who are paying the voluntary page charge will get the reprints free.

"Hopefully, members of the Society will understand why this change is necessary. Our membership

dues are very low in comparison to other similar scientific societies. It has been possible for a member

who published two articles in one year to get back as much as S30.00 on his $10.00 membership fee.

While finances were rosy, this could be tolerated. but with science and economics being what they are

today, the Society can no longer grant this gift.”

--American Journal of Botany Reprint Policy. PSB 17(2): 18

40 years ago

“The rapid decrease in the natural vegetation of the world is of great concern to all botanists. The waste-

ful and flagrant violation of man's stewardship over forests, plains, marshes and estuaries has appalled

generations of botanists, but the complexity of solutions to these problems (which necessarily includes

political, legal and social components) has eluded us and has discouraged too many of us from actively

working toward solutions.

"The International Union for Conservation of Nature and World Wildlife Natural Resources has pre-

pared a detailed strategy of global dimensions for the United Nations Environmental program. This

strategy provides for active participation of botanists in the making of decisions regarding future use

of plant and other resources. Thirty countries (including the United States) have already pledged their

support to this proposal, as have also the international monetary organizations.”

--Salute to World Conservation Strategy. PSB 27(3): 17-18.

PSB 67(2) 2021

101

Thanabotany: the Emerging Field

Where Plants, People and

Death Intersect

By Cole Imperi

Thanatologist,

Chaplain, Deathworker

Founder, School of

American Thanatology

E-mail: cole@american-

thanatology.com

Imagine this: it’s 2018 and an independent

thanatologist from Cincinnati, Ohio embarks

on a research fellowship exploring the

intersection of plants, people, and death.

What results is a new field of study called

thanabotany. Three years later, this emerging

field now has students and researchers from

20 different countries around the world.

I am that independent thanatologist who made

her way into the world of botany through

that fellowship. If thanatology is a new word

for you, you’re not alone. Put most simply,

thanatology is the study of death and dying.

The word thanatology was coined in 1905, yet,

things have been dying long before 1905! Take

this as proof of how death-avoidant humanity

truly is. I am a dual-certified thanatologist

and will be triple-certified later in 2021. I’m

interested in changing the way we approach

death and loss in my lifetime, and that’s my

life’s mission. Thanabotany is a part of that.

Thanabotany is the word I coined to describe

this emerging field, and I’m excited to share

with all of you what’s happened in the last

three years. Hopefully, I’ll lure some of you

over!

While under a fellowship, funded by the

Lloyd Library & Museum, I was shocked to

discover that there weren’t really any texts

solely dedicated to discussing how plants

have been used for death, dying, grief, loss,

and bereavement, despite the fact that every

human being experiences death and loss.

Every living thing dies, so how were there

no books focused on this specific area? So

many religions, cultures, and communities

have plant-based rituals across time and into

modern day that prescribe how specific plants

are to be used before death, at death, and after

death. How was there no guidebook?! How

was there no central text?

WHAT IS

THANABOTANY?

Thanabotany is where ethnobotany—the study

of the plant–person relationship—intersects

with thanatology—the study of death and

dying. In thanabotany, we want to understand

how humans have used plants to deal with

death, dying, grief, loss, and bereavement.

From funerary rituals to body preservation

to social behaviors, thanabotanical practices

appear across different times, cultures,

religions, and countries.

Under my fellowship, it was a challenge to find

information about these practices offered as a

primary focus. I have a huge research database

at this point, and all of the information about

these practices have been pulled out of books

PSB 67(2) 2021

102

and texts piecemeal. I’d find a paragraph here,

or maybe half a page on one death-related

plant practice there. As my research deepened,

I found much of the written information

about plants and death buried under clouded

or avoidant language. Instead of a text saying,

“For grief, make a tea of violets,” it would

substitute words like hysteria or lunacy in place

of grief. How many of you, in the aftermath of

a significant loss, have had the experience of

feeling out of your mind or completely not in

normal reality? That’s grief, not lunacy—and

it’s normal. Truth be told, we still are lagging

in our understanding and acceptance of grief

in modern day, so it is no surprise that what

humanity has recorded isn’t clear and direct

about it. This has proven to be an exciting

challenge for those of us in this emerging field

attempting to save this recorded information.

In thanabotany, we seek to understand

not only what plants were used for death,

dying, grief, loss, and bereavement, but also

why, how, and by who. We are interested in

understanding how thanabotanical practices

from the past are still alive today and how

they can be restarted in a modern context.

THANABOTANY TODAY

I now have students and researchers studying

thanabotany with me from 20 countries, across

10 time zones and spanning ages from 18 to

83 years old. Our courses have lessons broken

into videos, slide presentations, reading

assignments, class discussions, live lectures,

tests, and an active community, which allow for

real-time communication and collaboration

between students during and after courses.

It’s all spread by word of mouth and via social

media. Within 9 months of publishing a single

podcast episode about thanabotany in 2019,

it had been played in 42 countries more than

1000 times. I’ve been invited to speak about

thanabotany to a wide variety of audiences,

from associations for funeral directors to

universities to international organizations.

The outside interest is real, and it has been a

challenge to keep up with—but it shouldn’t

have come as a surprise, since interest and

experience with both plants and death spans

cultures around the globe.

In a recent issue of the Plant Science Bulletin

(Vol. 66, No. 3), I learned that there has been a

decrease in the number of botany departments

in higher education across the United States.

I’m happy to share that, a new independent

botany department has emerged! Housed

under the School of American Thanatology

(which I founded in 2020), we are the only

place offering programs in thanabotany

today. Additionally, we now officially have

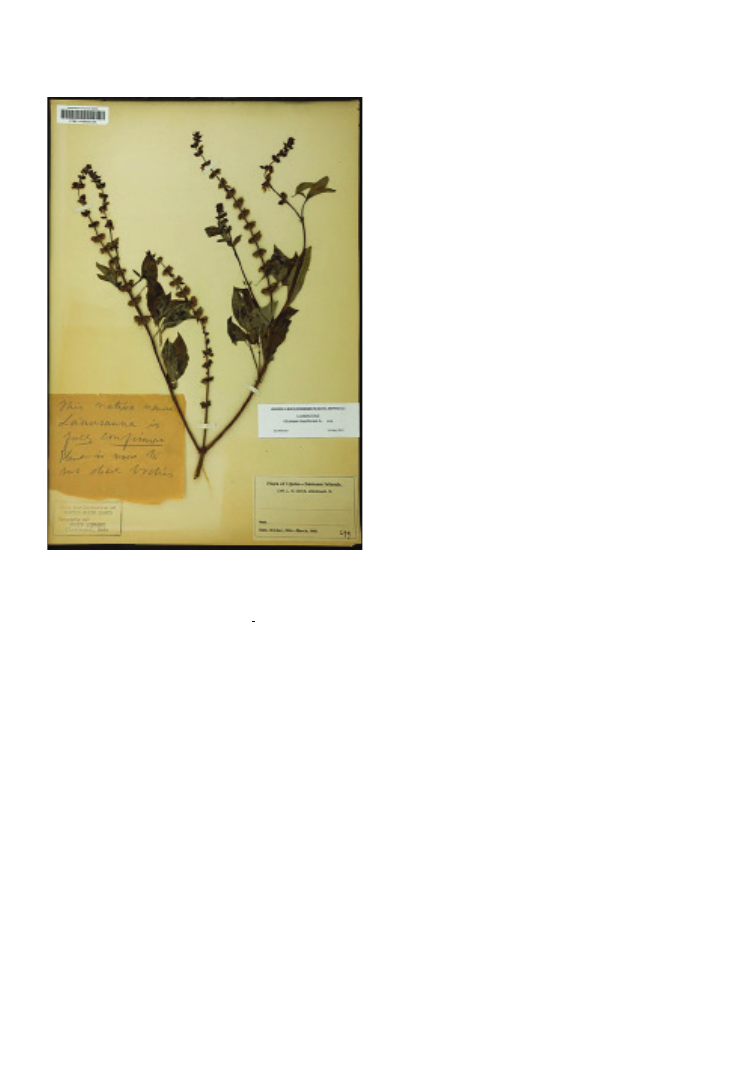

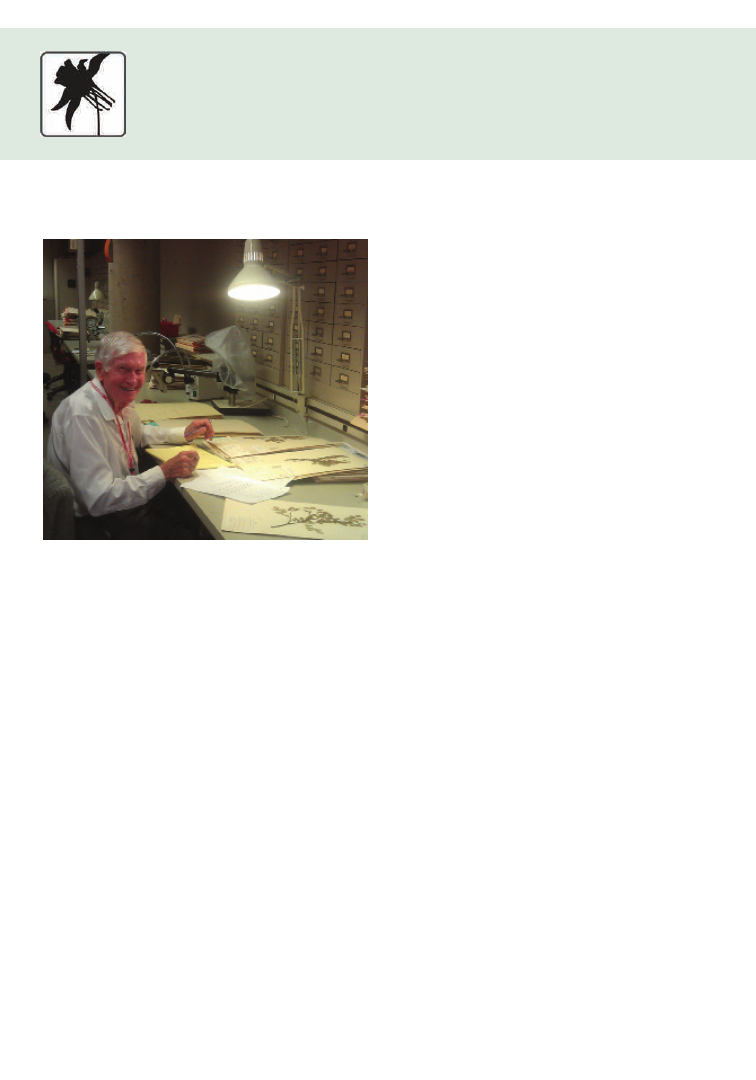

an herbarium! The Margaret H. Fulford

Herbarium at the University of Cincinnati

is the home herbarium for the Thanabotany

Department at the School of American

Thanatology. They will house a thanabotanical

collection comprised of specimens submitted

by our students worldwide (Fig. 1). We want

to capture modern-day thanabotanical plants,

and details about their usage. The Margaret H.

Fulford Herbarium is a dream herbarium for

us. It houses 127,000 specimens of vascular

plants, bryophytes, fungi, lichens and wood

samples. The herbarium also houses the

research of Margaret H. Fulford, a pioneering

liverwort researcher, and the collection of E.

Lucy Braun, a plant ecologist. For an emerging

field, we are very proud of what has been

accomplished in such a short time.

PSB 67 (2) 2021

103

Figure 1.

Specimen of Ocimum basilicum L.

housed at the Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium

at the University of Cincinnati; https://midwes-

therbaria.org/portal/collections/individual/

index.php?occid=15326114&clid=0.

Margaret

H. Fulford Herbarium.

CINC-V-0000103Lloyd,

Curtis Gates 2791904-10-00. Samoa, Upolu,

Upolu, -13.924665 -171.739014.

WHERE IS THE INTEREST

COMING FROM?

How has this gone from an independent

research fellowship to an emerging field with

students and researchers from 20 countries

in 3 years? I think there are a few important

factors:

An Increased Interest

in Plants

The COVID-19 pandemic has no doubt fueled

a lot of change. Many people have been forced

into time at home they didn’t have before.

This time has revealed to a lot of people what

actually makes them happy, how they really

want to live their lives, and what they truly

care about. As a result, many Americans have

discovered a newfound interest in plants.

During the pandemic, houseplants became

an accessible and necessary link between

people and nature. Growers across the United

States have reported a surge in sales through

2020 and the need to eat into 2021’s plant

stock sooner than anticipated (https://www.

greenhousemag.com/article/2021-the-year-

of-flexibility/).

One of the most common things self-reported

by students on my intake survey is the number

of houseplants currently in their homes, or

how large their garden is. It’s not uncommon

for me to have a student with 80+ houseplants

at home.

Changing Views on

Education

In the United States, the way higher education

is perceived and valued is changing, and

I would argue—has changed. Many of my

students come to the School of American

Thanatology to learn about something they

care about as directly as possible. In a way,

there seems to be a prestige—I’m using

actual verbiage from my students here—in

studying with an independent institution like

PSB 67(2) 2021

104

mine. Students want to cut out the middle

man, so to speak, and the middleman is the

“institution.” They want the professor. They

want the person. They don’t want the school.

When I started the school, my big concern

was our lack of accreditation by a larger body.

I didn’t know how I would make time to figure

out which accreditations mattered, let alone

finding the time or resources to devote to those

lengthy processes. I came to find, however,

my students don’t care about accreditation.

They view it as a fee the school likely has to

pay that inflates the cost of education, but as

a professional in the field, I do still care about

it. While leading a young institution, pursuing

accreditation helps me express my care and

value for our work. I value my peers, and I

want my colleagues to trust my commitment.

For those of you reading this with perhaps a

niche knowledge in something plant related,

let this be encouragement to you to try teaching

what you want to teach independently and

directly to the people who want to learn from

you. People want to learn from people with

passion, no matter their home.

WANTING TO TAKE

MORE ACTION

Last year was no joke, and 2021 certainly

isn’t either. Between the political upheaval,

social change, racial injustice, lockdowns and

distancing, 2020 left people asking WHAT.

What can I do, with what I have, where I am?

How can I contribute? How can I have an

impact?

Plants are humanity’s original best friends.

There is an opportunity to take care of ourselves

through the plant–person relationship and our

communities through the plant–community

connection. Many of my students want to

learn how to be in a relationship with plants

again, or maybe for the first time ever.

Thanabotany focuses on not only historical

research, but also what can be done now, where

you already are. We need people recording

their modern-day traditions and rituals with

plants and death now. And we need to collect

specimens alongside our written records.

Thanabotany is a chance to honor, record,

and preserve this relationship and take real,

positive action. People can participate in the

field from wherever they are in the world.

They just need an internet connection.

WHO IS INTERESTED IN

THANABOTANY?

There are two answers here: people who want

to study thanabotany and people who want to

use it.

Based on surveys my students take when they

enroll, my students come from a wide variety

of professional backgrounds. The following

is a selected list of job titles reported by my

students:

• Arborists

• Arboretum professionals

• Artists

• Attorneys

• Board-certified physicians

• Currently enrolled college students

• Educators (K-12 and college)

• Field botanists

• Funeral directors

• Genealogists

• Government workers

• Human resource professionals

• Insurance salespeople

PSB 67(2) 2021

105

• Librarians

• Non-profit executives

• Parks and recreations staff

• Psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and coun-

selors

• Registered nurses

• Retail managers

• Software company executives

• Veterinarians and veterinary staff

• Zoologists

Since 2019, I have kept a list of the inquiries

that come into my website and comments I

get after my talks from people who are seeking

thanabotanical information. Here’s a selected

list of groups/professions who have expressed

a desire to have access to information from

the field of thanabotany for use within their

own contexts:

• Arboreta

• Cannabis and CBD companies/products

• Cemeteries

• Chefs/cooks

• City planners

• Clergy

• Embalmers

• Florists

• Funeral directors

• Gardeners

• Genealogists

• Grievers

• Grocery stores

• Hospices

• Historians

• Horticultural therapists

• Indigenous leaders looking to reconnect

their modern communities to their for-

gotten death practices

• Journalists

• Landscapers

• Nurseries

• Parks and recreation staff

• Sommeliers

• Teachers

• Writers

• Veterinarians

• Zoos

THANABOTANY IN

REAL LIFE: FUNERAL

SERVICE

Louis Linnemann, President of Linnemann

Family Funeral Homes and Cremation Center

in Northern Kentucky said, “When Cole

presented her talk about Thanabotany at the

Annual Meeting of the Northern District of

Funeral Directors and Embalmers, we knew

immediately that the use of flowers and plants

would have an application to funeral service.”

One of their Funeral Directors, Bart Pindela,

was able to immediately take what he learned

about thanabotany at that talk and run with

it. “Thanabotany can provide a meaningful

and memorable connection for families to

their deceased. Plants not only serve as an

expression of sympathy but can be used as a

catalyst for connecting families to the memory

of their deceased,” said Pindela. “Through the

recommendation of the local Thanatologist,

Cole Imperi, I have used rosemary in place

of filler greens in a casket spray. This was

very appropriate because the deceased was

a native of England, where rosemary has a

symbolic and historical connection to funeral

ritual and grief. A few of the rosemary plants

were planted at the graveside and the rest

were taken home by the family to be planted

in their gardens. After the funeral services

were over, a family member thanked me for

recommending the use of rosemary. She said

that rosemary, an herb she overlooked before,

now holds a lasting connection to her mother.

Her comment made me appreciate the

potential of plants to serve families on their

PSB 67(2) 2021

106

path through grief. Plants used during funeral

services are not just expressions of sympathy

but can offer survivors a connection to their

loved ones that continues past the day of the

funeral service.”

This is, in my view, one of the best possible

applications of thanabotany. It provides

additional tools to those in professional roles

(in this case, to funeral directors), and it helps

people move through the grieving process

and find meaning. Research consistently

shows that when we can identify something

with meaning—whether that’s a rosemary

plant or something else—we are likely to live

longer and be healthier. Thanabotany provides

opportunities for plant professionals, as well

as lay people, to find a meaningful role in the

field.

THANABOTANY IN

REAL LIFE: CEMETERY

ARBORETUMS

Did you know that many historic cemeteries

have worked to become arboretums?

Once they “fill up,” they have the time and

resources available to put back into the

landscape. Gertrude Lorenz—an Ecological

Designer, Rewilding Specialist, Certified

Permaculturalist and Board Member at

Historic Linden Grove Cemetery & Arboretum

in Covington, Kentucky—said, “There are

infinite possibilities for Thanabotany at Linden

Grove—from green burials and scattering

gardens to traditional burials and existing

grave sites. Each space is an opportunity for

the use of plants to speak for and about our

loved ones. In addition to the benefit to each

family during the grieving process, it opens

up the wider conversation in the community

about how our natural world has a language

of its own and how it is constantly speaking

to us. It provides a beautifully meaningful

pathway into developing closer relationships

with the individual plants around us which

will ultimately move beyond the cemetery

and flow out into our everyday lives. Nature

is one of our core values at Linden Grove

and many of our current efforts are moving

towards alignment with this value and so

Thanabotany couldn‘t be more on point with

the type of practices we need. Ultimately, it

creates a higher quality experience for our

community and a more refined conversation

around grieving and nature. Thanabotany is

a perfect fit for Linden Grove, but I think it

would be for any cemetery.”

Linden Grove is currently in the process

of installing a thanabotanical garden with

specimens connected to the loss of children

and healing from grief. This includes trees,

shrubs, and flowers with recorded usage

practices related to this specific type of loss

and/or to remedies for grief recovery.

THANABOTANY

ISN’T NEW

Academic and research applications of

thanabotany can provide new ways of looking

at an entire collection, or even a single

specimen. Dr. Eric Tepe, Assistant Professor

and Herbarium Curator at the University of

Cincinnati’s Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium,

pulled a magnificent specimen from their

collection with a special note that would be of

particular interest to a thanabotanist:

“The specimen of basil collected by C.G.

Lloyd in Samoa is interesting for a number

of reasons,” said Tepe. “First, it is native

to Africa and Asia, so probably arrived

PSB 67(2) 2021

107

in Samoa relatively recently. Its culinary use is obvious, but the fact that it was adopted for

more ritualistic purposes—"rubbing dead bodies”—in that short time is interesting. Lloyd

collected ethnobotanical data for only a few of his Samoan collections, and the extra data that

accompanies this specimen makes it especially valuable. According to Art Whistler’s Plants in

Samoan Culture, coconut oil is used traditionally to absorb plant aromas, which is then used

as a perfume, for massages, and ‘in the past, for embalming the dead.’ He doesn’t comment on

when this practice was abandoned, but the Lloyd specimen could be on the tail end.”

FINALLY

In the last three years, the growth of thanabotany worldwide, without much effort on my part

to market or advertise it, is what has shocked me the most. It doesn’t surprise me, however,

that people are interested. Plants and death are universal experiences. Both are natural. I

look forward to seeing where things are in another three years, and if you read this and find

yourself interested in being a part of an emerging field, please reach out! You can find me at

AmericanThanatologist.com, and you can find the school at AmericanThanatology.com.

PSB 67(2) 2021

108

There are a few things that I particularly enjoy when being a teaching fellow for the class OEB

52 - Biology of Plants at Harvard University: the process of how students gradually became

very familiar with the concept of alternation of generations, the moments when they were

surprised or impressed by random facts of plants, the times when they tell me how they started

to pay more attention to plants around them—and my favorite is when their final creative arts

projects were finally revealed. In this class, we require all students to complete a final creative

project to illustrate the “rise of sporophyte,” and students have their full artistic freedom to

create a project in any form and format. This is definitely the highlight of the class every year,

and we were blown away by their creativity every single time.

We got submissions in songwriting, song adaptations, interpretive dances, yoga lessons,

drawings (watercolor, pencil, vector art, pixel art, sand art—just to name a few), clay art, stop

motion videos, time-lapse videos, song playlists, children’s books, games (e.g., broad games,

online video games), recipe books and menus, magazines, embroidery, puzzles, essays, poems,

and more. A video trailer about the creative projects of the class was made in 2017 and can

be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EKsgJ_8PEZIVX8-A5dyj1YLaI23BEm4V/

view?usp=sharing.

This year, one of my students, Jude Okonkwo, composed a beautiful poem for his final project,

and I was particularly touched by it. I encouraged him to publish it in the Plant Science Bulletin

because I felt this poem can touch many botanists’ hearts and inspire more people to express

the love and thoughts for botany with arts and literature.

Enjoy! --Min Ya, Harvard University

Poetry Corner

PSB 67(2) 2021

109

Part 2:

Like a sailor who sees in the boundless ocean image

a home

and the weary sojourner

who digs through the desert sands for water I have

sought the shimmers of love’s delightful mirage

Do u grasp too at stones

in hopes of finding a drop of human feeling in this

cold world

Have we not seen what men can do?

how a boy can lie against pavement for nineteen hours

and be left unattended

I often wonder how people mill about knowing that at

any hour their souls can be seized from them

that the oxygen that courses through their blood will

dissipate

leaving behind a temple of tissues, scars and bones

And just like that!

(What is that evolution that pushes this haunting from us?)

But here we are!

(Where in my bones is this escape from fear?)

But I have known the aroma of love just as well

that which dwells like an oracle in the depths of the living

like a shivering fern who hides her child in a

vegetable womb

her lifeblood food for her offspring to eat

like the moss that shrinks the body in a flush of humility

nearing the molecule water that will carry on his

fertile seed

and isn’t that all I desire

that in ages after my body has folded back into soil

that another will arise to roam with a speck

of my heart

that another will love with a hint of my soul

Part 1:

when your bare feet taps against the clovers in the

pavement cracks doesn’t it tear you from the webs of

photography and the allure of lights and guide you to a

more primal home

in the city, do you ever press beyond the concrete

dominion and gaze again at the phantoms of great oak

and bristling vine that once defined our heaven

what does it mean for man to yearn for what cannot

be seen what does it mean for woman to seek what

cannot be understood

I knew a man who sailed a boat to the center

of the Caspian and threw himself into the sea

he said there was pleasure to be found in abandon-

ment in the roar of the water flush against the ears and

the burn of salt scraping up against the skin

was this his atonement for the way we live

a way out of the urges that bind and prod us to build

larger gadgets, larger toys, larger lives as a means of

escape

a botanist taught me that men aren’t the only ones that

seek escape from the body that

sporophytes too push against the structure that God gave

pushing against the body wall, hoarding sunlight and

oxygen

growing further and faster in order to shed parts of

themselves into the wind with hopes of finding refuge

somewhere beyond

In Lasting

By Jude T. Okonkwo

Project Goal: In nature, there is a selective pressure for sporophytes to grow larger in order to

disperse spores by air and a selective pressure for gametophytes to grow smaller to take advantage

of films of water for sperm dispersal. Additionally, heterospory and endospory are traits that

evolved to allow sporophytes to become the dominant generation and these traits have evolved