IN THIS ISSUE...

SPRING 2019 VOLUME 65 NUMBER 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Establishing a BSA Student Chapter... p. 53

CATB Isolation: The True Story, by Jeff

and Jane Doyle... p. 15

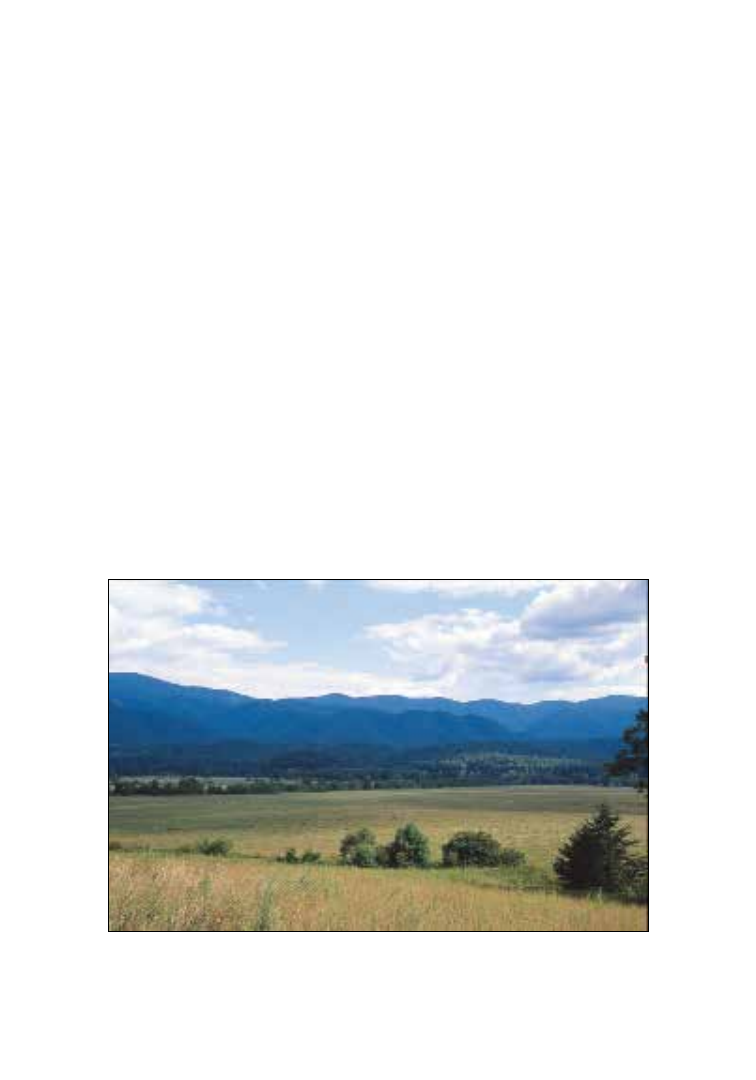

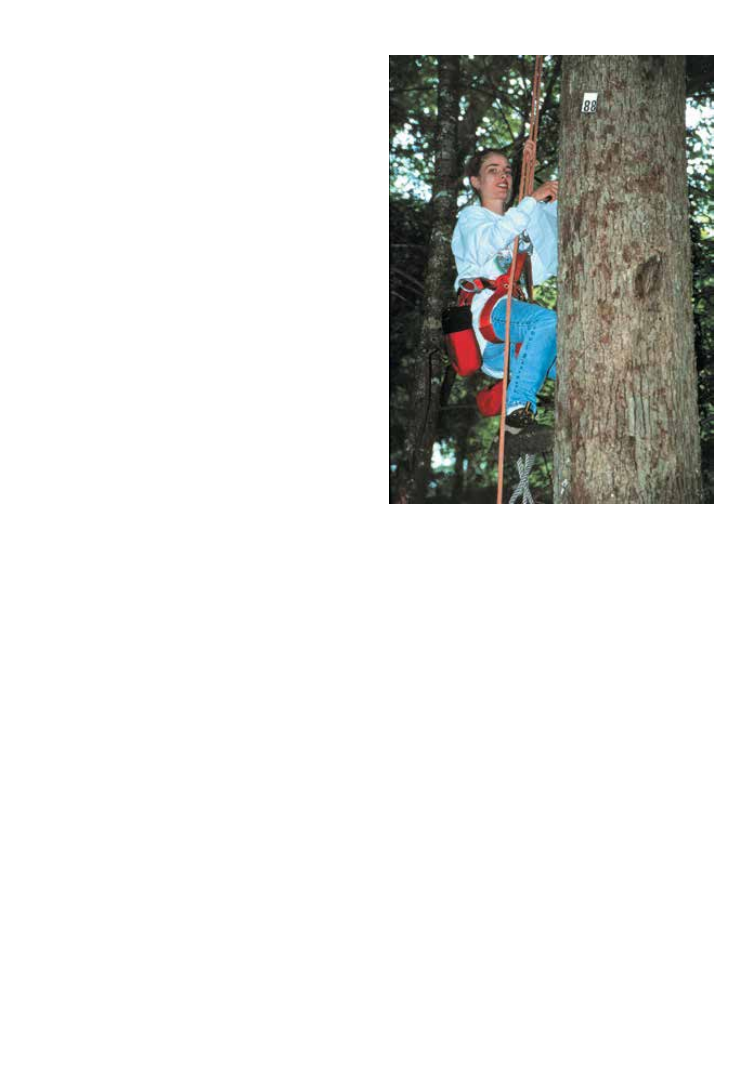

Student Team-Based Tree Canopy

Biodiversity Research... p. 28

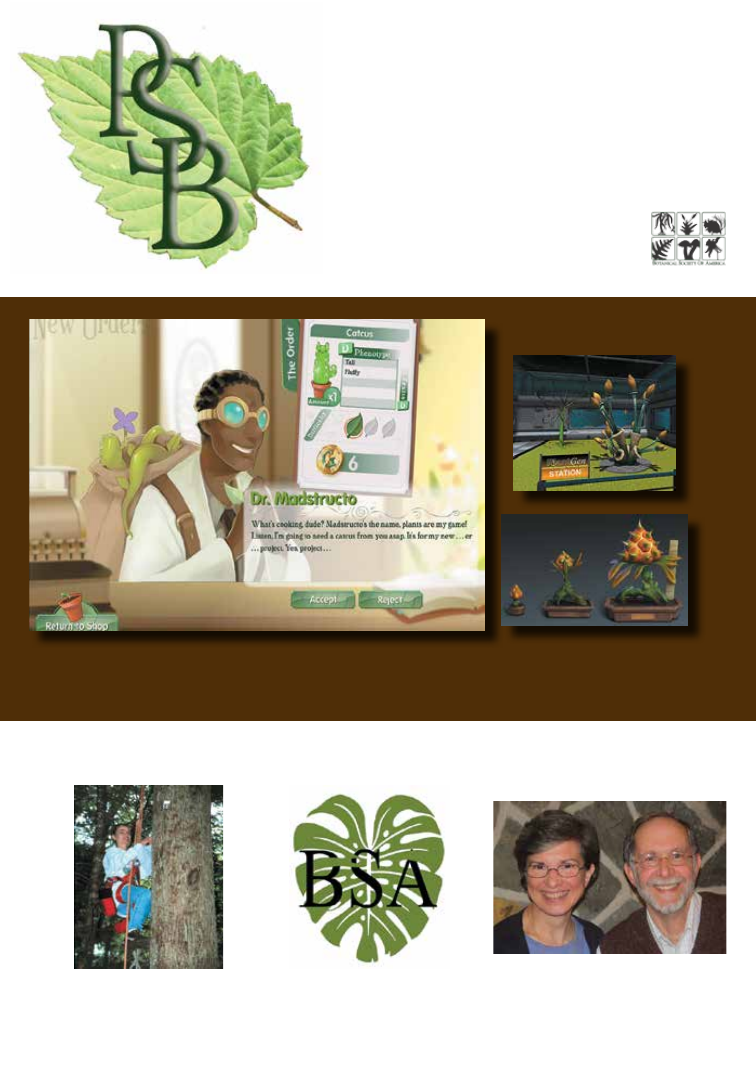

Botany as a State of Flow

Enhancing Plant Awareness through Video Games

Spring 2019 Volume 65 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 65

From the Editor

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

melanie.link-perez

@oregonstate.edu

Shannon Fehlberg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

Greetings,

In this eclectic issue of Plant Science Bul-

letin, we have the story of 2× CTAB iso-

lation, a discussion about the potential of

using video games to promote botanical

education, and a description of canopy re-

search in Great Smoky Mountain National

Park. In the Policy Notes, you will find the

latest information about the Botany Bill,

and the Student Section highlights oppor-

tunities for students.

I am also happy to point you toward our

large assortment of book reviews in this

issue. As always, we are grateful for the

reviewers who take the time to provide a

synopsis and critique of the newest bota-

ny-oriented books, as well as the publish-

ers who make these titles available. If you

are interested in writing a review, the list

of available books can be found at https://

botany.org/home/publications/

plant-science-bulletin.html. We also wel-

come reviews of books that are of interest

but not on our list. For more information,

please contact me at mackenzietaylor@

creighton.edu.

I want to send a special shout-out to our

readers and BSA members who are U.S.

federal employees and who endured the

longest-ever—at least at the time I am

writing this—government shutdown in

January. Your service to botany, science,

and to the United

States is appreciated.

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

2

By Krissa Skogen (Chicago Botanic Garden),

Kal Tuominen (Metropolitan State University),

and Andrew Pais (North Carolina State University

[not pictured]), the BSA PPC Co-Chairs

Public Policy News

In response to the increased interest in science

advocacy, the Public Policy Committee of the

BSA is dedicated to providing resources and

examples of advocacy strategies to help the

scientific community more effectively engage

with policy makers. In 2019, the Plant Science

Bulletin’s Public Policy News will highlight

upcoming legislation, organizations, and case

studies to facilitate greater engagement.

FEATURED LEGISLATION:

REBOOTING

THE BOTANY BILL

If you have been involved or interested in

advocating for the Botany Bill during the past

two years, we need you to spread the word

ENGAGE IN BOTANICAL

SCIENCE ADVOCACY!

and connect with your elected officials in the

116th Congress!

The Botanical Sciences and Native Plant

Materials Research, Restoration, and

Promotion Act (aka the “Botany Bill”) was

introduced to the 115th Congress in the

U.S. House of Representatives (2017; H.R.

1054) and Senate (2018; S.3240). With a new

Congress comes the need to reintroduce

the Bill and a new opportunity for it to

move forward in the legislative process! The

“Botany Bill” will be reintroduced in the

116th Congress in both the House and Senate

once co-sponsors are identified, ideally in

early 2019. In order for the Bill to make it

to committee, it will need broad bipartisan

support in both the House and the Senate.

Consider contacting your elected officials

and asking them to co-sponsor the Bill!

We will need all the support we can get—

your efforts are needed and valued!

Visit https://botanybill.weebly.com/ for

resources to guide your advocacy efforts,

for information on the new version of the

Botany Bill, and to sign up for updates on

the Bill!

SOCIETY NEWS

PSB 65 (1) 2019

3

FEATURED ORGANIZATION:

THE PLANT

CONSERVATION ALLIANCE

The Plant Conservation Alliance (PCA) is a

public-private partnership of organizations

that share the common goal of protecting

native plants by ensuring that native plant

populations and their communities are

maintained, enhanced, and restored. The

partnership includes 12 U.S. Federal Agency

Members (the Federal Committee) and

nearly 400 Non-Federal Cooperators (the

Non-Federal Cooperators Committee),

which is comprised of state agencies and

private organizations interested in native

plant conservation in the United States.

PCA Members and Cooperators work

collaboratively to solve the problems of

native plant conservation and native habitat

restoration, ensuring the sustainability of

ecosystems in the United States. The depth and

strength of PCA lies in the scientific expertise,

networking, and ability to pool resources to

protect, conserve, and restore our national

plant heritage for generations to come.

In 1995, PCA developed the National

Framework for Progress in Plant Conservation

(https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/

programs_natural-resources_native-plant-

communities_national-seed-strategy_pca_

Framework.pdf). This Framework is intended

to provide a coordinated approach to plant

conservation in the United States. The National

Framework consists of six broad strategies and

outlines supporting goals and actions to guide

efforts for implementing a national plant

conservation strategy at national, regional,

and local levels.

Cooperators are invited to attend meetings

of the PCA’s Federal Committee as observers,

participate in informal open forums with

the PCA Federal Committee, and participate

in PCA Working Groups. Cooperators also

receive regular communications that facilitate

participation in Non-Federal Cooperator

Committee efforts to raise awareness about the

importance of native plant conservation. In

addition, the PCA holds bi-monthly meetings

as an open forum for anyone interested

in working in plant conservation. The

meeting takes place in the Washington, DC

metropolitan area and is available remotely

as a live webinar. Attendees use a roundtable

format to share relevant events and discussion

on work related to plant conservation, and each

of the PCA working groups and committees

provides ongoing updates. Regular attendees

include representatives from PCA Federal

agencies and from cooperating organizations.

However, anyone is welcome to attend the

meetings.

Get Involved with the PCA!

Join the PCA listserv to learn about upcoming

meetings, receive announcements, and follow

discussions on native plant conservation:

http://lists.plantconservation.org/mailman/

listinfo.

Visit http://www.plantconservationalliance.

org/cooperators to find out if your organization

or agency is part of the PCA.

The schedule for upcoming meetings

can be found at http://www.

plantconservationalliance.org/meetings.

Follow the PCA on Facebook at https://www.

facebook.com/PlantConservationAlliance/.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

4

In Memoriam

HUGH DANIEL WILSON

(1943–2018)

Hugh Daniel Wilson was born in Alliance,

Ohio, to Fern and Elvin Wilson on August 15,

1943 and died November 5, 2018.

He grew up in Alliance and graduated from

Alliance High School in 1961. He was a

running back on the AHS 1958 Football State

Championship team and held a track record

at the Ohio State Relays that lasted for nearly

20 years. Hugh was elected to Alliance High

School Athletic Hall of Fame in 2000.

Sargent Hugh Wilson was honorably

discharged from the United States Air Force 1964-68

with an Air Force medal of Commendation

for Meritorious service in Vietnam.

After returning from the service, Hugh

completed a Bachelor of Arts (Biology) in

1970 and Master of Arts (Botany) in 1972 at

Kent State University, Kent, Ohio. Thesis: “The

Vascular Plants of Holmes County, Ohio”.

Hugh received his Ph.D. in Botany and

Anthropology 1973-1976 from Indiana

University, Bloomington, Indiana Dissertation:

“A biosystematic study of the cultivated

chenopods (Quinoa) and related species”.

After earning his Ph.D., Hugh was a visiting

professor on the faculty in the Department of

Botany at the University of Wyoming, Laramie,

Wyoming. Hugh had full responsibility for a

five-week Science Camp offering field Botany.

In 1977, Dr. Wilson joined the faculty at

Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas

(College of Science), Department of Biology.

He taught Taxonomy of Flowering Plants, Field

Systematic Botany, and Economic Botany until

he retired in 2011 as Professor Emeritus.

Dr. Wilson was known for the study of the

floras of Ohio and Texas, with focus on

conservation of rare species and habitats,

and for his ethnobotanical research and early

molecular work on Lagenaria, Cucurbita, and

Chenopodium. His enthusiasm for taxonomy,

ethnobotany, floristics, conservation, and

specimen digitization inspired many of his

students to become botanists or pursue related

fields, and I am lucky to count myself among

them.

Dr. Wilson was the curator of the TAMU

Herbarium (now combined with Texas A&M’s

Tracy Herbarium, TAES) and was an early,

visionary promoter of specimen digitization,

herbarium data standards, online collections

browsers, and regional consortium building—

many years before these ideas became widely

embraced and adopted. He was instrumental

in the creation of one of the earliest online

PSB 65 (1) 2019

5

herbarium specimen browsers (for TAMU

and TAES), and provided leadership for both

iterations of the region’s herbarium consortia

(first, the Digital Flora of Texas Consortium,

and later, the Texas-Oklahoma Regional

Consortium of Herbaria (TORCH)). Wilson’s

insistence that botanical data should be

digitized so they could be easily shared and

updated, and then eventually combined and

mined for research—long before Big Data

was a thing—made him a pariah, in his own

opinion. In my opinion, he is one of the giants

upon whose shoulders many of us now stand.

Hugh was given the Edmund H. Fulling

Award, Society for Economic Botany,

1981, Fellow American Association

for the Advancement of Science 1990.

He received support for research from

the National Science Foundation, U.S.

Department of Agriculture, and National

Geographic Society.

Dr. Wilson was a member of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science,

the Botanical Society of America, the

American Society of Plant Taxonomists, and

the Society for Economic Botany.

Hugh is survived by his wife, C. Toni (Favazzo)

Wilson, College Station, TX; son, Quentin F.

Wilson, Portland, Oregon; brother, Gary L.

Wilson, Los Angeles, CA., nephews, Derek M.

Wilson, Dallas, TX, C.D. Wilson, Sachem, CT;

and their children.

In lieu of other forms of commemoration,

please take the time to accompany your

students in their fieldwork, or invite them to

accompany you in yours.

(Dr. Wilson’s obituary was published in the Alli-

ance Review on 10 November 2018. We present

it here with additions by Amanda K. Neill.)

LANNY FISK

(1944–2018)

Dr. Lanny Herbert Fisk (1944-2018), beloved

brother, father, and friend, left the Earth and

life he loved on July 19, 2018. He resided in

Grass Valley, California. Lanny was born to

Paul J. and Mildred (Courser) Fisk on February

24, 1944. He graduated from Vestaburg

High School in 1962. In January of 1967 he

married Carolyn McDowell of Detroit, MI.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army and served

as a Medical Specialist at the U.S. Pentagon

from 1967-1969. Following his honorable

discharge, he moved to Berrien Springs,

MI where he completed an undergraduate

degree at Andrews University in 1971. After

earning his PhD in Biology, with emphasis

on Paleobotany, from Loma Linda University

(LLU) in Loma Linda, CA, he taught at

Walla Walla College (WWC) in Walla Walla,

WA. He then pursued postdoctoral studies

in Petroleum Geology at Michigan State

University.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

6

Life-long research took Lanny around the

world, but his favorite was conducted at

Yellowstone National Park (YNP) where he

had graduate students working under him

doing research on the petrified forests of

YNP. His research, often in collaboration

with valued colleagues, has been published

in several journals, including but not limited

to The Journal of Paleontology. Geological

Society of America (GSA) was the first

professional organization he joined and went

on to become a member of the Paleontological

Society as well as too many others to name.

He held teaching positions at WWC, LLU,

and most recently, American River College

in Sacramento, CA. While at LLU, he and

Dr. William J. Fritz incorporated F & F

GeoResource Associates, Inc. In 1982 Lanny

created, as the Senior Paleontologist and

Chief Executive Officer, the consulting firm

of PaleoResource Consultants, DBA of F &

F. In 1993 he was appointed by the Governor

of Oregon to serve on the Board of the

Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral

Industries, which he did through 1998.

Lanny was very active in AASP-The

Palynological Society over the past many

years. He was President of the Society in 2014;

prior to that he was President-Elect (2013)

and then Past-President (2015). While he

was President-Elect he hosted and organized

the 2014 AASP-TPS Annual Meeting in San

Francisco. Lanny fulfilled many wishes of

hosting that meeting in San Francisco, with

a ’60s theme t-shirt, the venue in downtown,

and a geologically oriented field trip to the

wine country. Over the past decade Lanny was

ever present at AASP-TPS annual meetings,

giving presentations, participating in board

meetings, and participating in other Society

activities.

Right up until his passing, Lanny was

organizing projects and studies involving

fieldwork and travel. He was full of incredible

energy and enthusiasm. He had just been

talking with Joyce Lucas-Clark about a new

project on the California Eocene-Oligocene

stratigraphic problems, and had longer-

term plans for working on the Chalk Bluffs

microflora. Appropriately, Lanny passed away

while working at his computer in the office

late at night. He had dreams of projects right

up until the time of his death. No one knew

the extent of his health problems other than

his knee replacements. Despite those surgeries

and normally bringing up the rear with Joyce

on hikes, he thoroughly enjoyed fieldwork.

Throughout his professional career, Dr. Fisk

was a lecturer, teacher, and mentor to many

in the geology and paleontology community.

In 1996 Lanny married Tami Wanner. Their

children are Daniel (21), Michael (19), and

Dessa (16), who all live in the Sacramento

area. Lanny’s family also includes his sisters,

Paula Fardulis of Carlsbad, CA, and Susan

Brantley of Vestaburg, MI. Lanny had valued

relationships with many cousins, nieces and

nephews, great nieces and great nephews, who

tolerated the teasing and practical jokes that

came along with his wit. Those of us who were

close to him have lost a very good friend.

-Joyce Lucas-Clark and Thomas Demchuk

Excerpts taken from Legacy.com

Reprinted from the AASP – The Palynological

Society Newsletter 51 (4): 15-16.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

7

NEIL ARTHUR HARRIMAN

(1938–2018)

Neil Arthur Harriman died at home on

December 7, 2018 after a rather lengthy

decline in his health.

Neil was born on August 1, 1938 in St.

Louis, Missouri, the only son of Ruth and

John Harriman. He grew up in St. Louis along

with his older sister, Ruth. Neil received his

Bachelor of Arts from Colorado College,

Colorado Springs, Colorado, in 1960, followed

by a Doctor of Philosophy from Vanderbilt

University in Nashville, Tennessee, in Biology

in January 1965.

While at Vanderbilt, Neil met Bettie Ralph and

they were married on July 13, 1963. Together,

they moved to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in

September of 1964 when Neil joined the

Biology Department faculty at University of

Wisconsin Oshkosh (UWO), primarily to

teach botany classes and do plant taxonomy

research. Neil remained at UWO until his

retirement in May 1998.

Neil was a dedicated teacher and found

great satisfaction not only in teaching about

botanical information, but helping the students

learn to be life-long learners. It gave him much

pleasure that three of his students went on to

get their own PhDs in Botany: Robert Jansen,

Bruce Parfitt (deceased), and Melanie DeVore.

His research work of collecting, identifying,

and conserving plants was also a pleasure to

him. When Neil arrived on campus in 1964,

the herbarium facility in Halsey Science

was barely more than a room with cabinets

waiting to be filled with dried, identified,

and properly labeled plants, arranged in a

systematic fashion. Today it houses almost

125,000 specimens from around the world,

including over 70 type specimens; three

of these document species named in Neil’s

honor: Flyriella harrimanii, Lundellianthus

harrimanii, and Phyllanthus harrimanii. After

Neil’s retirement, the university named the

herbarium in his honor. The Neil A. Harriman

Herbarium contains not only plant specimens,

but Neil’s extensive personal botanical library

as well.

Neil belonged to numerous botanical societies

during his career, including American Society

of Plant Taxonomists, for which he served a

three-year term as Secretary and Program

Chairman, and the International Association

for Plant Taxonomy. He served as Editor

of The Michigan Botanist for many years,

and as a reviewer and author in the Flora

of North America project of the Missouri

Botanical Garden. Over the years he published

numerous scientific articles in the journals of

these societies.

During his 34 years as a member of the UWO

faculty, Neil received a number of awards and

recognitions. In 1973–1974, he was given the

Citation as an Outstanding Teacher. In May

1986, Neil was named a John McNaughton

Rosebush University Professor for Excellence

PSB 65 (1) 2019

8

in Teaching and Professional Achievement.

In 1993 he received the UWO Endowment

for Excellence - The TRISS Endowed

Professorship.

When Neil retired in 1998, he was named

Professor Emeritus of Biology and

Microbiology at UWO by the Board of Regents

and continued to work in the herbarium as

long as his health allowed.

Neil’s joy for editing the written word extended

beyond botany, as did his willingness to “help

out” when needed. During his retirement,

Neil joined his wife Bettie as co-editors for

the quarterly journal of the Wisconsin Society

for Ornithology from 2003 to 2014. He also

contributed his editing skills to the production

of the Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin, a

600-page book published by the Wisconsin

Society for Ornithology in 2006.

The essence of Dr. Neil A. Harriman is

perfectly stated by one of his graduate

students, Tom Eddy: “Forty years ago, as a

young graduate candidate at the University of

Wisconsin Oshkosh, I was encouraged by Dr.

Neil A. Harriman to conduct a systemic study

of the vascular flora of Green Lake County. My

thesis research and association with Neil

resulted in a profound change in my life

trajectory, both personally and professionally.

“Besides our independent plant collecting,

Neil and I participated in numerous botanical

outings organized by the Botanical Club

of Wisconsin. Neil’s taxonomic knowledge

was encyclopedic. He exercised a superlative

command of language and proper use of

grammar. Whether in lecture or private

conversation, he could turn what first

appeared to be a collection of unrelated facts

into a relevant lesson, frequently accompanied

by humorous euphemisms.

“Neil was an unpretentious and modest

person, preferring not to draw attention to

himself. In 2009, the herbarium which Neil

founded in 1964, was dedicated in his honor:

the Neil A. Harriman Herbarium. While such

an honor might offer one an opportunity to

grandstand, Neil chose not to speak at this

ceremonious tribute.

“The natural world was held in reverence

by Neil. Whether botanizing a natural area,

roadside right-of-way, or parking lot, his eye

was trained on the ground. Besides collecting

new plant records, Neil regularly collected and

properly disposed of someone else’s litter.

“Neil gifted generously to his local animal

shelter. He held a tender spot for cats and dogs

waiting to be adopted. On numerous occasions

I witnessed a similar mindfulness by Neil

toward other peoples’ lives whose unfortunate

circumstances were less than ideal. He was

generous, big-hearted and aspired for the

common good. For all this, I owe Neil a debt

of gratitude for his mentorship and unflagging

friendship.”

Neil is survived by his wife Bettie and many

friends who offered comfort and assistance

with his care. His final week was under the

excellent care of Aurora At Home hospice

care, which gave much physical support and

comfort to Neil in a most experienced and

professional manner while at the same time

providing an easy emotional and caring

support for Bettie.

-Thomas G. Lammers, Ph.D., Professor Emeri-

tus, Department of Biology and Microbiology,

University of Wisconsin Oshkosh

PSB 65 (1) 2019

9

Heather Cacanindin was named the BSA

Executive Director in March 2018, after a

competitive search to replace Bill Dahl, who

retired in October 2017. Prior to taking over

the reins of the Society, Heather served as the

Director of Membership and Marketing for the

BSA, the Society for the Study of Evolution, and

the Society for Economic Botany for over 10

years.

Why did you want to be the Executive

Director of the BSA, and what makes you

excited to come to work?

I have spent my entire career in association

and nonprofit work. I love working for

organizations that are truly mission-driven

and making an impact on the communities

that they serve. After ten years at the BSA,

I felt that I had a deep understanding of the

organization, its culture, and our staff and our

members’ needs. BSA does such a great job in

serving its members in every career stage, and

our members are doing fantastic and exciting

research and outreach. It is invigorating to

know that we are all here to nurture scientific

discovery, provide professional development

opportunities, and pave the way for the next

generation of botanical scientists. I find that

there are so many dedicated members and

leaders in this organization, and that makes

coming to work each day really worthwhile

and fulfilling. I know the rest of our staff feels

the same way. And also, our BSA staff is just

fantastic to work with!

What is the most surprising or challenging

thing you have encountered in your first

year as Executive Director?

It was surprising to me just how long it took

to get up to speed in an organization that had

been my home for several years. There were

still so many aspects of our business that I had

only tangentially been exposed to. I realized

quickly that there was still so much for me to

learn at the BSA, and that was challenging, a

little scary, and exciting all at the same time.

In what way is serving in this role different

than you imagined?

It’s hard for any organization to transition

from a long-time Executive Director to a new

leader. I don’t think I realized just how much

our Board, members, and staff were looking

to me to set the tone and direction for the

next phase of BSA’s evolution. I also realized

quickly that it was hard for me to let go of

some of my previous work that was familiar

and comfortable in favor of some of the new

initiatives and work on my desk as Executive

Director. Luckily, with the help of our staff,

leadership, and a terrific new Membership

Manager to fill my previous role, I have been

able to make the pivot.

5 Things About Your Executive Director

PSB 65 (1) 2019

10

Who is a person who has influenced and/or inspired you in your work?

I had a fantastic mentor at the United Soybean Board, when I worked there several years ago.

She taught me to always put forth my best effort, do my research, and really listen to my leaders

and constituents. I also learned from her that sometimes you have to speak your mind and

stand up to your leadership if they are getting off track or engaging in mission-creep. Running

an association is a partnership between the leadership and the staff, but the direction of the

organization really rests with the members and the mission of the organization. She also taught

me that it is important to continue to sharpen my skills and support my staff in their own

professional development. Thanks, Janice!

And finally... what do you like to do in your spare time?

I love to read, travel, and watch my two sons play hockey.

Applications in Plant Sciences

Two Special Issues This Spring

The March issue of Applications in Plant Sciences is focused on “Emerging

frontiers in phenological research.” This special issue, organized by guest editors

Gil Nelson, Elizabeth Ellwood, and Katelin Pearson, includes articles presenting

innovative phenology projects—

all of which make use of, or can be applied to,

herbarium specimens

—that offer

new insights into research methods, software,

and foundational standards and practices.

The full issue is available at

https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/21680450/2019/7/3.

APPS will feature another special issue in April, with “Methods in Belowground

Botany.” Guest editors Gregory Pec and James Cahill have curated a diverse group

of papers that explore current methods and challenges in investigating plant root

systems, ranging from the sub-cellular to the ecosystem level, with a wide variety

of applications that advance our understanding of belowground botany.

Upcoming articles for this issue are available at

https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/21680450/0/0.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

11

The publishing landscape is changing constantly, and authors have many options for publishing

their research. The BSA’s two peer-reviewed journals—the American Journal of Botany and

Applications in Plant Sciences—want to be the home for your work!

How do your Society journals stand out in today’s crowded publishing field?

• AJB and APPS have a broad international reach, which is increasing even further through

our partnership with Wiley.

• As a BSA member, you can publish for free in AJB, and you receive discounts for

publishing in APPS (a totally Open Access methods journal). See member benefits for full

details.

• Our editorial boards have broad botanical expertise and handle papers with great care and

efficiency (the average time to first decision is ca. 30 days).

• Your BSA publications team—Amy McPherson, Beth Parada, and Richard Hund—

works with authors, reviewers, and editors to maintain high standards and an efficient and

constructive process from manuscript submission through publication.

• We support authors post-publication through social media promotions, press releases,

and other outreach.

There is an added bonus for publishing in AJB and APPS: As nonprofit Society journals, our

proceeds go back to the BSA’s members and the botanical community to support grants and

awards that further careers and opportunities.

Submit articles now for AJB at https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/15372197/

homepage/forauthors and for APPS at https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/

journal/21680450/homepage/forauthors.

We look forward to seeing your best research appear in your Society journals!

The Benefits of Publishing in

BSA’s Research Journals

12

ANNOUNCEMENTS

NEW ONLINE

CERTIFICATE IN

TROPICAL

FOREST LANDSCAPES

The Environmental Leadership & Training

Initiative (ELTI) is proud to announce the

launch of a new online certificate program, in

collaboration with the Yale School of Forestry

& Environmental Studies, titled: Tropical

Forest Landscapes: Conservation, Restoration

and Sustainable Use.

This yearlong program consists of four eight-

week online courses, a capstone project, and

an optional field course in Latin America

or Asia. This program is designed for

professionals working to address the complex

social, ecological, and funding aspects of

managing tropical forest landscapes.

Learn from a diverse team of Yale faculty

members, ELTI team members, and a network

of international partners:

• Fundamentals: Ecological and social

concepts

• People: Community and institutional

engagement

• Strategies: Implementing and monitoring

techniques

• Funding: Financial concepts and tools

• Capstone: Designing a conservation or

restoration project

The program will run from June 2019 through

May 2020. Applications open January 7, 2019.

Interested in learning more? Visit our website

at tropicalrestorationcertificate.yale.edu for

more information and sign up for our mailing

list to receive important program updates.

MSC

DEGREE/POSTGRADUATE

DIPLOMA IN THE

BIODIVERSITY AND

TAXONOMY OF PLANTS

Royal Botanic Garden

Edinburgh,

University of Edinburgh

Programme Philosophy

The MSc in Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants

is a full one-year master course established by the

University of Edinburgh and the Royal Botanic

Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) in 1992 to address

the growing worldwide demand for trained

plant taxonomists and whole-plant scientists.

Since then the course has developed into the

ideal platform for the study and understanding

of plants and their conservation. The RBGE

course is unique in its broad approach

with a strong emphasis on plants and their

identification. Students will also have the once-

in-a-lifetime opportunity to be part of a two-

week field trip to Colombia to undertake

tropical plant identification.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

13

The MSc is ideal for those wishing to develop

a career in many areas of plant science:

• Survey and conservation work in

threatened ecosystems

• Assessment of plant resources and genetic

diversity

• Taxonomic research

• Management of institutes and curation of

collections

• A stepping stone to PhD research and

academic careers

The course and students benefit widely from

the close partnership between RBGE and the

University of Edinburgh (UoE). RBGE has

one of the world’s best Living Collections

(>15,000 plant species across our four

specialist Gardens—5% of world species),

an Herbarium of three million specimens,

and one of the UK’s most comprehensive

botanical libraries. The School of Biological

Sciences at UoE is a center of excellence for

research in Plant Sciences and Evolutionary

Biology. Recognized experts from RBGE,

UoE, and from different institutions in the UK

deliver lectures across the whole spectrum of

plant diversity. Most course work is based at

RBGE, close to major collections of plants,

but students have full access to the extensive

learning facilities of the university.

Edinburgh is a unique place to study plant

taxonomy and diversity. RBGE is one of

the top four botanic gardens in the world

and a global leader in plant science and

conservation. The organization dates back to

1670 and will celebrate its 350th anniversary

in 2020. Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city, is

also a unique and vibrant city in which to live

and study, welcoming students from around

the world.

Aims and Scope

The MSc provides biologists, conservationists,

horticulturists, and ecologists with a wide

knowledge of plant biodiversity, as well as a

thorough understanding of traditional and

modern approaches to pure and applied

taxonomy. Apart from learning about the latest

research techniques for classification, students

should acquire a broad knowledge of plant

structure, ecology, statistical methodology,

and plant identification.

Program Structure

This is an intensive 12-month program and

involves lectures, practicals, workshops and

essay writing, with examinations at the end

of the first and second semesters. The course

starts in September of each year and the

application deadline is normally 31 March.

Topics covered include:

• Evolution and biodiversity of the major

plant groups, fungi and lichens

• Plant geography

• Conservation and sustainability

• Production and use of floras and

monographs

• Biodiversity databases

• Phylogenetic analysis

• Population and conservation genetics

• Tropical field course, plant collecting and

ecology

• Curation of living collections, herbaria

and libraries

• Plant morphology, anatomy and

development

• Molecular systematics

PSB 65 (1) 2019

14

Fieldwork and visits to other institutes are

an integral part of the course. There is a

two-week field course to Colombia in which

students are taught a unique approach to

tropical plant identification using mainly

vegetative characters, field collections, and

ecological survey techniques. The summer is

devoted to three months of a major scientific

research project of the student’s choice or a

topic proposed by a supervisor. These research

projects link in directly with active research

programs at RBGE

Entry Requirements

Applicants should ideally hold a university

degree, or its equivalent, in a biological,

horticultural, or environmental science,

although any well-motivated applications

from other fields will be considered, as

we are looking above all for candidates

having a genuine interest in plants. Relevant

work experience is desirable but not

required. Evidence of proficiency in English

must be provided if this is not an applicant’s

first language.

Funding

There are a few funding options from the

University of Edinburgh. Other international

funding bodies have supported overseas

students in the past.

Further Information

For further details on the program, including a

course handbook, please visit the RBGE website:

https://www.rbge.org.uk/learn/professional-

courses/msc-postgraduate-diploma-

in-the-biodiversity-and-taxonomy-of-

plants/ or https://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/

postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/

view&edition=2018&id=1.

If you have any questions or queries, you are

most welcome to contact the Course Director

at RBGE, or the Postgraduate Secretary of the

University of Edinburgh:

MSc course Director,

Dr. Louis Ronse De CraeneRoyal

Botanic Garden Edinburgh

Tel +44 (0)131 248 2804

E-mail: lronsedecraene@rbge.org.uk

Postgraduate Program Secretary,

The University of Edinburgh

School of Biological Sciences

The King’s Buildings

15

SPECIAL FEATURES

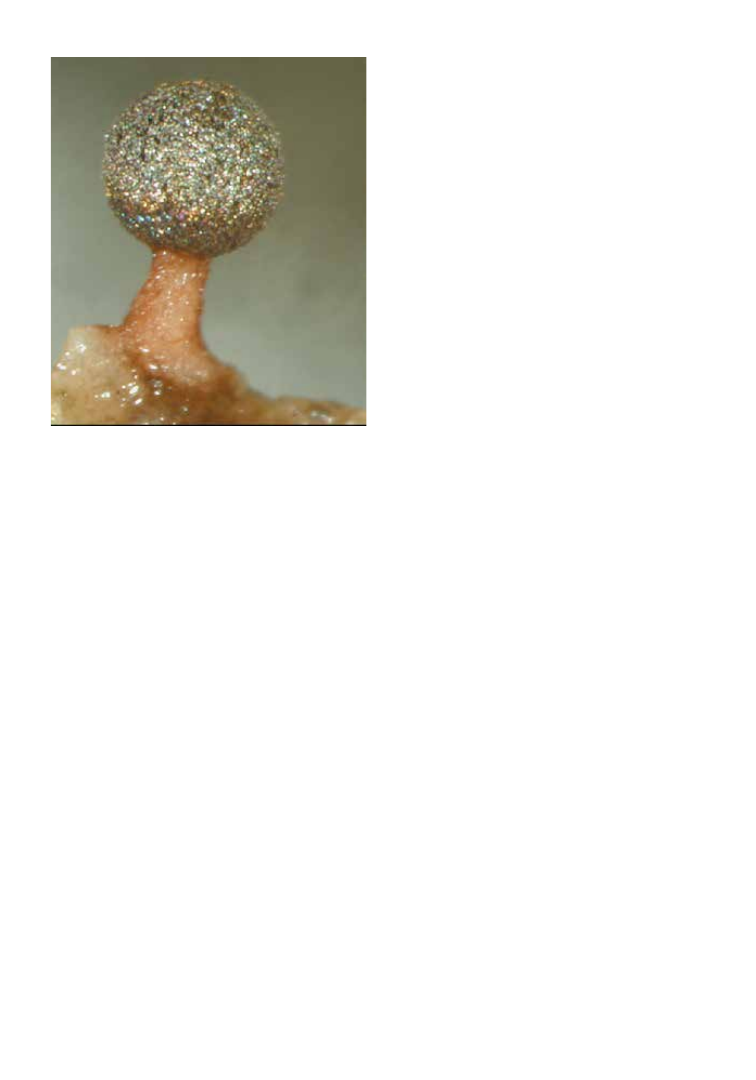

A

critical step in a molecular systematic

study is the isolation of DNA suitable

for subsequent use. In the early 1980s, plant

molecular biology was in its infancy, confined

initially to model species—primarily maize

and other cultivated plants (the Arabidopsis

era was still some years away). DNA typically

was isolated from large amounts of tissue, often

20 g or more, most commonly by laborious,

expensive, several-day protocols that required

CsCl density gradient ultracentrifugation and

yielded low amounts of DNA, often broken

down. For many questions, particularly

systematics and population biology, quick

and inexpensive methods suitable for large

numbers of samples were needed.

In the laboratory of Roger Beachy at

Washington University in St. Louis, where Jeff

was a postdoc with Roger and Walter Lewis,

and Jane a technician from 1981 to 1984, as

well as after our move to Cornell in 1984, we

experimented with a number of published

and unpublished “miniprep” methods,

particularly Appels and Dvorak (1982), with

variable success on different species and

tissues, while continuing to use the CsCl

method taught to us by Liz Zimmer (Rivin

et al., 1982) for large-scale leaf isolations. In

1985, we tried a protocol we found in a paper

on ribosomal RNA gene (rDNA) variation in

barley (Saghai-Maroof et al., 1984)—rDNA

restriction fragment length polymorphisms

were then a cutting-edge systematics tool—a

useful-looking DNA isolation protocol using

the detergent cetyltrimethylammonium

bromide (CTAB) that the authors described

as a modification of a method by Murray and

Thompson (1980).

Our notebooks show that we did our first

CTAB isolation using the Saghai-Maroof et al.

(1984) protocol on May 8, 1985, using 0.13 g of

Glycine tomentella and 0.44 g of Pseudovigna

CATB Isolation: The True Story

By Jeff J. Doyle and Jane L. Doyle

School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant

Breeding & Genetics Section and Plant

Biology Section

Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853

PSB 65 (1) 2019

16

argentea. The result: “Insoluble pellets!” A day

later we were back to using the Appels and

Dvorak (1982) method, and continued to use

that while we experimented with a method for

isolating pure chloroplast DNA (Bookjans et

al., 1984). But we were also still in the market

for a total DNA miniprep, and hadn’t given

up on CTAB, trying the Saghai-Maroof et al.

(1984) method again in August, and once more

in December, without great success. Then, in

the lab notebook on January 17, 1986, is a

note to “try using 2× Saghai-Maroof CTAB

bfr. (they used lyophilized tissue!).” Doubling

the buffer concentration compensated for the

water content of the fresh leaf tissue we were

using, which had diluted the detergent—the

modification worked, and from that point on

we switched to 2× CTAB in our lab for all of

our miniprep isolations.

In the summer of 1986, at the AIBS conference

at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst,

we participated in a discussion at the BSA

Phytochemical Section meeting about the

new DNA approaches that were bringing the

estimation of relationships closer to the level of

the gene than could the use of flavonoids and

other secondary compounds. It was decided

that the Phytochemical Section should offer

itself as a home for this form of “molecular

systematics,” and, to further that goal, we

were invited to publish the 2× CTAB protocol

in the Phytochemical Bulletin. We accepted

the invitation, and Doyle and Doyle (1987)

appeared in the January-March issue of that

quarterly periodical, edited in 1987 by David

Giannasi, and comprising approximately 30

printed pages stapled together and included

with the American Journal of Botany mailing

to members of the Section. Over 10,000

citations later, one might say of this simple

modification of someone else’s procedure that

“the rest is history”… but the story only got

more interesting after that publication.

With an effective DNA isolation protocol in

hand, we worked with Elizabeth Dickson,

then a graduate student in our lab, on a series

of experiments using dried, frozen, and

preserved leaves, to determine the conditions

under which DNA suitable for restriction

digests could be obtained with the 2× CTAB

method. Those results were reported in

Taxon in 1987 (Doyle and Dickson, 1987), in

a paper that, although it is the only version

of the protocol published in a conventional

journal, has been cited only 286 times. Two

years later we were asked by a representative

of Bethesda Research Laboratories, Inc., a

major provider of restriction endonucleases

at the time, to publish the 2× CTAB protocol

in their trade publication, Focus; that version

appeared as Doyle and Doyle (1990) and has

now been cited over 11,000 times. In 1990 we

were asked to present tutorials on molecular

methods at a NATO workshop on “molecular

taxonomy” and published a set of “DNA

Protocols for Plants” (Doyle and Doyle, 1991)

in the workshop proceedings volume. That

paper has been cited over 750 times.

In 1992, during a seminar trip to Texas A&M

University, we met a faculty member, Brian

Taylor, who informed us that he had published

a protocol identical to the 2× CTAB method in

1982, also in Focus (Taylor and Powell, 1982).

We had been completely unaware of this—as,

apparently, had been the editor of Focus! We

also learned that in 1985, Rogers and Bendich

(1985) had published a method based on that

procedure and on the even earlier protocol of

Murray and Thompson (1980), and had used

it, as we later did, to test the ability of DNA

to survive under conditions of drying and

preservation. Their paper has been cited over

1200 times.

We have never tried to take full credit for

this protocol; Saghai-Maroof et al. (1984) is

PSB 65 (1) 2019

17

mentioned in the abstract of the Phytochemical

Bulletin paper, and the text states that the

method is “a very simple modification of

a procedure originally described for barley

by Saghai-Maroof et al. (1984), differing

principally in that their procedure called for

using lyophilized tissue, while we use fresh

leaf material, and have compensated for the

increased water content by increasing the

concentration of the extraction buffer.” For

years, when people have requested copies

of the protocol from us—typically librarians

who cannot find either Phytochemical Bulletin

or Focus, both of which are nearly impossible

to locate because of, apparently, not being

conventional journals—we have sent a PDF

file that provides, along with the protocol

itself, a short version of this history, including

providing as much of the reference to the

Taylor paper as we have (“Taylor and Powell,

1982, Focus 4: 4-6”) and the history he related

to us. We could have saved ourselves a lot of

time and effort—at the expense, it is true, of

over 20,000 citations!—had we known of the

existence of these other CTAB protocols in

the 1980s. But it should be remembered that

finding relevant papers was a major task in

the days before the internet made searching

the vast literature simple. We found Appels

and Dvorak (1982) and Saghai-Maroof et al.

(1984) not because of their DNA protocols,

but because they discussed rDNA evolution.

By a series of accidents of fate, the two

Doyle and Doyle protocols (1987, 1990) have

been used worldwide now by generations of

scientists, and it is not uncommon for us to

be asked to pose for photographs with people

at international conferences because of this,

which is a bit embarrassing. An article in

Nature (Van Noorden et al., 2014) discussed

the 100 most-cited papers in the history of

science—which in 2014 meant papers with

at least 12,000 citations in the Thompson

Reuters collection of over 58 million papers.

None of our papers reporting the 2× CTAB

method made the top 100 list, nor would they

even now—but if summed they would have

qualified as the 48th most cited paper of all

time. Considering the topics of these most

highly cited publications, Van Noorden et

al. (2014) noted that papers reporting useful

protocols dominated the list, and summed

up with the following quote: “If citations are

what you want, devising a method that makes

it possible for people to do the experiments

they want at all, or more easily, will get you a

lot further than, say, discovering the secret of

the Universe.” The 2× CTAB procedure is a

prime example!

LITERATURE CITED

Appels, R., and J. Dvorak. 1982. The wheat ribo-

somal DNA spacer region: Its structure and varia-

tion in populations and among species. Theoreti-

cal and Applied Genetics 63: 337-348.

Bookjans, G., B. M. Stummann, and K. W. Hen-

ningsen. 1984. Preparation of chloroplast DNA

from pea plastids isolated in a medium of high

ionic strength. Analytical Biochemistry 141: 244-247.

Doyle, J. J., and E. E. Dickson. 1987. Preservation

of plant samples for DNA restriction endonucle-

ase analysis. Taxon 36: 715-722.

Doyle, J. J. and J. L. Doyle. 1987. A rapid DNA

isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh

leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19: 11-15.

Doyle, J. J. and J. L. Doyle. 1990. Isolation of

plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13-15.

Doyle, J. J. and J. L. Doyle. 1991. DNA and high-

er plant systematics: some examples from the le-

gumes. In: G. Hewitt, A. W. B. Johnson, and J. P.

W. Young (eds.), Molecular Techniques in Taxon-

omy. NATO ASI Series H, Cell Biology Vol. 57,

pp. 101-115.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

18

Murray, M. G., and W. F. Thompson. 1980. Rapid

isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA.

Nucleic Acids Research 8: 4321-4325.

Rivin, C., E. Zimmer, and V. Walbot. 1982. Isola-

tion of DNA and DNA recombinants from maize.

In Maize for Biological Research, ed. W.F. Sheri-

dan. Plant Molecular Biology Association and

University of North Dakota Press, pp. 161-164.

Rogers, S. O., and A. J. Bendich. 1985. Extraction

of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbar-

ium, and mummified plant tissues. Plant Molecu-

lar Biology 5: 69-76.

Saghai-Maroof, M. A., K. M. Soliman, R. A. Jor-

gensen, and R. W. Allard. 1984. Ribosomal DNA

spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: men-

delian inheritance, chromosomal location, and

population dynamics. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of Amer-

ica 81: 8014-8018.

Van Noorden, R., B. Maher, and R. Nuzzo. 2014.

The top 100 papers. Nature 514: 550-553.

Register Now!

Early registration deadline May 31!

www.botanyconference.org

SYMPOSIA AND

COLLOQUIA

TOPICAL PRESENTATIONS

INFORMATIVE POSTERS

FIELD TRIPS

WORKSHOPS

PSB 65 (1) 2019

19

N

o doubt my botanical leanings can

be attributed to an innate sense of

connection with plants. From an early age, I

began to wonder what it must be like to be a

plant; I even started my own garden at the age

of 10. I admit that I was deeply influenced in

my choice of interests. I was fortunate enough

to have a dad who introduced me to gardening

and horticulture. His immense gardens were

a thing to behold—flowers, vegetables, fruit

trees, all very productive and well-tended (in

part due to my conscripted labor). Then later, as

a teen, I had a high school science teacher who

inspired me to dig deep, to be curious, and to

appreciate and understand the science of plants.

Not many kids in the neighborhood

appreciated my garden. They would have been

what we now call plant blind (Wandersee and

Schussler, 2001). Sadly, nothing has really

changed since then, and the term is now

even used by the popular press (Blackhall-

Miles, 2015). Dugan (2016) points out that

our disconnect with plants and nature is

worsening, and that in Shakespeare’s time,

audiences were much more plant-savvy than

the urbanized populations of today. One sign

of the times is that the horticulture industry

Botany as a State of Flow

Enhancing Plant Awareness through Video Games

By David Ehret

Sunfleck Software

Sidney, BC Canada

cannot attract enough young people to fill the

available jobs (Higgins, 2018).

But since you are reading this article, it’s

probably safe to assume that you have more

than a passing interest in plants. You are

probably not plant blind. Perhaps, if you

are like me, you even find that when you

are working with plants, you enter a state of

bliss—a state of flow, as coined by psychologist

Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. Flow is a state

of total immersion or concentration, a state

where nothing else matters and happiness is

all there is. Csíkszentmihályi (1975) found

that this special state of mind often occurs

when playing games. The term has entered the

lexicon of video game culture to describe that

joyous state of complete and utter engagement

(Cowley et al., 2008).

Where does this state of bliss come from in

games? In her fascinating book Reality is

Broken, video game designer Jane McGonigal

KEY WORDS

digital educational tools, educational games,

gamification, plant appreciation, plant

blindness, video games

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Melanie

Stegman, Brandon Pittser, and Eliane

Alhadeff for their valuable insights, Dariusz

Andrulonis and Olga Samoilova for their

spectacular artwork, and Nathan Ehret for his

helpful suggestions and meticulous editing.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

20

(2011a) investigates the reasons why so many

people would rather be on an adventure in a

virtual world than live in the real one. She says

it’s because games offer four psychological

benefits that are often lacking in the real

world: satisfying work, the experience of being

successful, social connection, and meaning.

Well-designed games are, in effect, happiness

engines.

Video games offer an opportunity to

(re)ignite an interest in plants (Dugan, 2016).

In fact, a number of 21st-century electronic

tools are now being used to highlight the

importance of plants. The highly successful

YouTube channel Plants are Cool Too (https://

www.youtube.com/user/PlantsAreCoolToo),

produced by Chris Martine at Bucknell

University, and the Bloom video series (http://

www.seedyourfuture.org/BLOOM) produced

by the non-profit group Seed Your Future,

are making headway in engaging the public

in botany. Botany podcasts, websites, blogs,

and social media pages abound. However, one

glaring area of deficiency is video games.

Let’s have a look at some recent statistics from

the Entertainment Software Association (ESA,

2018):

• More than 150 million Americans play

video games, with 45% being female.

• Sixty percent of Americans play video

games daily.

• Gamers are getting older—the average

American female gamer is 36 and the

average male is 32, with about 12% being

over 50 in both cases.

And how much time is spent gaming? Recent

surveys from six countries, including the

United States, show about six hours per week

on average (Limelight Networks, 2018). That

may not sound like much, but consider the

long term: 15 years of playing, which is not

at all unusual, would be equivalent to all your

time spent in high school (estimated at 4682

hours). One should also consider scale. It’s

reputed (McGonigal, 2011b) that the players

of World of Warcraft have accumulated

more than 6 million years of gameplay, more

time than was needed for Australopithecus

to evolve into present-day humans. It’s an

astounding statistic, and one which makes

me wonder what education would look like

if that same commitment could be spent on

games meant for learning. Given that there

are 2.6 billion gamers worldwide (ESA, 2018),

playing within 15 genres and 40 sub-genres

(Wikipedia, 2018), surely there is room for the

creative development of games about botany.

To find out, I conducted an informal search

for games related to plants and botany on

two popular desktop platforms for games,

Steam and itch.io, and one mobile platform,

the Apple App Store. Some information

was also gathered for the Xbox 360 as a

console platform comparison. Steam is the

world’s foremost commercial distribution

site for desktop games, while itch.io is more

widely used for indie (independent) titles.

Approximately 2% and 1% of games available

on Steam and itch.io, respectively, were tagged

as educational (Table 1). No information was

available for the App Store, and the Xbox 360

lists only five games of 1291 (0.4%) as being

educational.

A fair number of games were tagged with

plant-related words such as forest, gardening,

nature, or farming, or had those words in

the title or description for all three platforms

(Table 1). This can be misleading. For example,

the term forest in the title does not necessarily

mean the game is about the plants in a forest,

but rather that the forest is a backdrop for the

game. For example, in Gardenscapes (Playrix

Games) and Blossom Garden (Legend

Dreams), the plants are largely incidental. In

PSB 65 (1) 2019

21

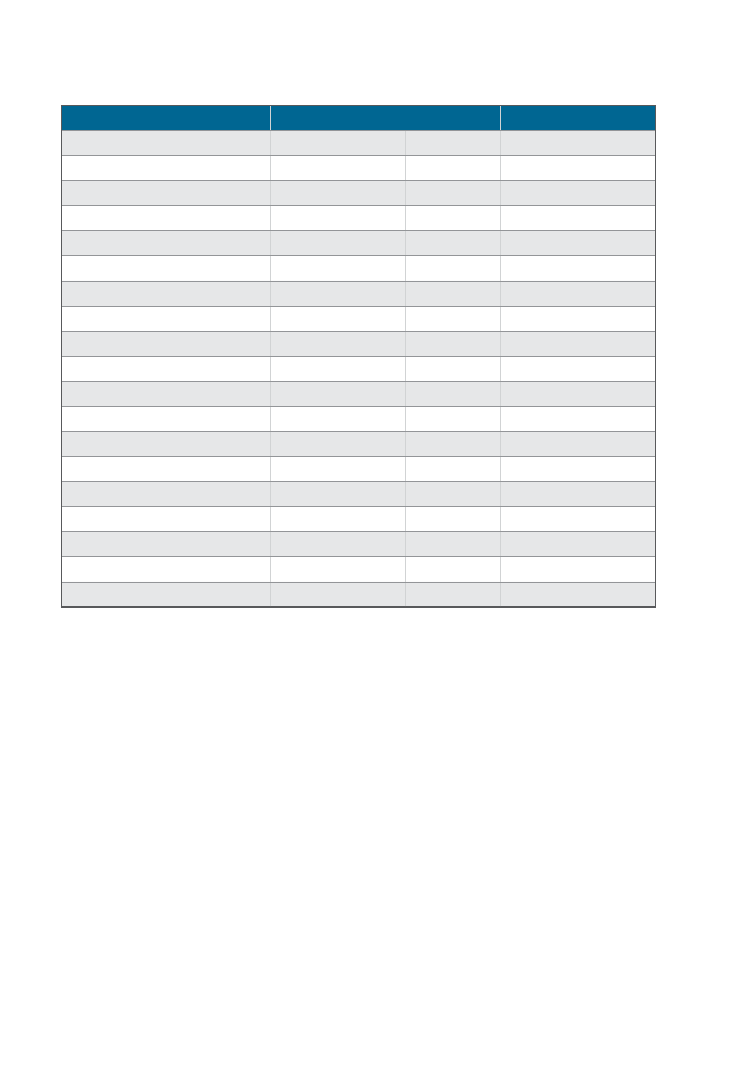

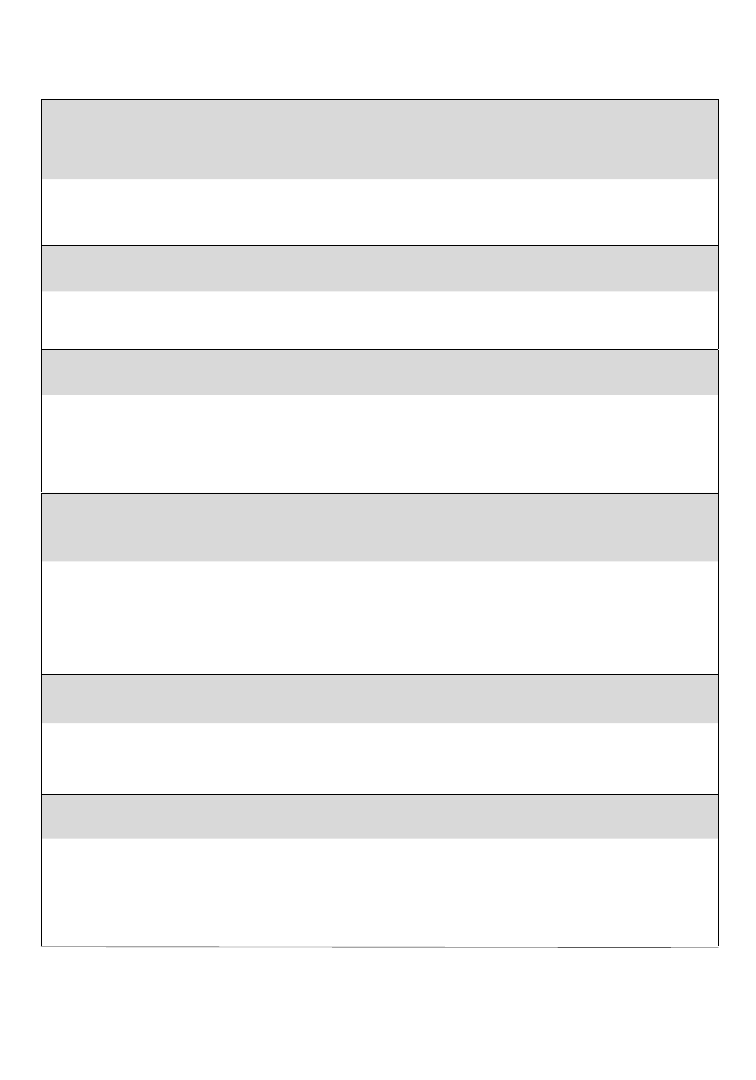

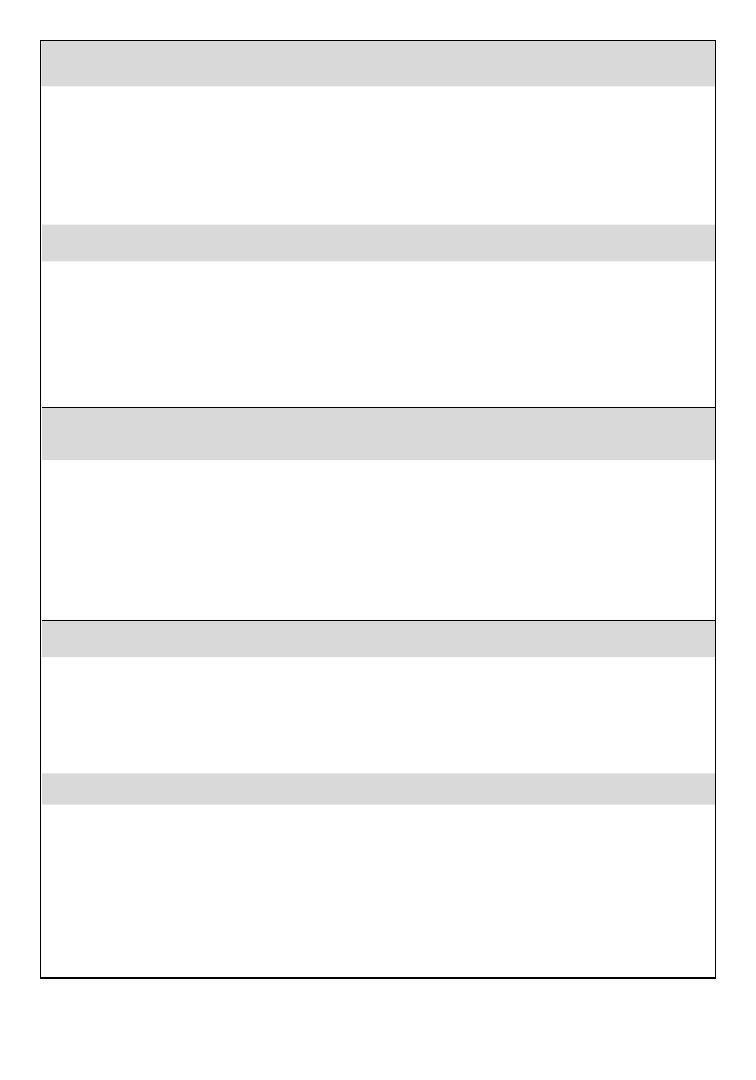

Search Term or Tag

Desktop

Mobile

Steam

1

itch.io

2

Apple App Store

3

Total Games

26,719

123,401

361,877

4

Educational

194

1,392

-

5

Forest

1119

145

134

Gardening

241

80

91

Nature

1125

314

152

Farming

511

256

133

Plants

568

0

58

Science

730

0

200

Botany

7

0

14

Educational & Forest

5

0

87

Educational & Gardening

2

1

22

Educational & Nature

11

13

104

Educational & Farming

3

4

196

Educational & Plants

10

0

135

Educational & Science

41

0

200

Educational & Botany

2

0

10

Table 1. Number of games found on different platforms.

1. Used a combination of search terms and tags, accessed August 25, 2018; URL:

https://store.steampowered.com/

2. Used tags exclusively, accessed August 24, 2018; URL: https://itch.io/

3. Used search terms exclusively with the fnd.io search facility, accessed August

25, 2018

4. Estimate provided by statista.com for first quarter, 2018.

5. Data not available.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

22

the tower defense game Plants vs. Zombies, by

PopCap Games, plants are obviously central to

the gameplay, but could just as well be insects

or robots.

Those games with plants forming an integral

part of the gameplay offer an opportunity

to fulfill two important roles. The first is to

raise awareness of plants without necessarily

teaching botany. Success here depends on the

objectives of the game developer. Botanicula,

by Amanita Design, is a beautifully stylized

point-and-click adventure game. The main

characters are botanical creatures on a

mission to rid their tree of evil parasites by

solving puzzles and collecting useful items.

The simulation game Viridi, by Ice Water

Games, has the player tending to succulents,

watching them slowly grow and flourish. The

atmosphere is meditative, and the primary

purpose is to relax the player. Similarly, the

main purpose of the adventure/art game

Flower, by that game company [sic], is to evoke

strong emotions. The open world adventure

game Skyrim (in the Elder Scrolls series by

Bethesda Game Studios) allows the player

to visit different biomes and to collect plants

with certain alchemical properties, thereby

elevating the role of plants in the game.

It also allows the player to mod (modify)

plants found in the game (for examples, see

Nexusmods at https://www.nexusmods.com/

skyrim/mods/58091/), which is an effective

way to get people thinking about plants. This

build-your-own plant idea is also used in

other games. In the adventure game Solarium

(Figure 1), by Sunfleck Software, the player

is a novice botanist in a futuristic world who

is given the opportunity to create her own

imaginative plants for doing well in training.

(Full disclosure: Sunfleck Software is my game

studio.) Finally, in a simulation aimed entirely

at creative expression, Mendel, by Owen Bell,

lets the player create an endless array of plant

forms and family histories, with the underlying

algorithms based on sound classical genetics.

The second role of plant-focused games is to

actually teach botany. Do these games exist?

When combining the education tag with

plant-related terms (Table 1), the number of

games drops for all platforms, although not so

much in the App Store (for unknown reasons).

So the answer is yes, but the percentages of

educational plant-related games on all three

platforms are very low.

The educational game category is not

mutually exclusive of other genres. There

is nothing to prevent a plant science game

from being educational but in the format of

an adventure or strategy game. Yet many

are simple quizzes, particularly on mobile.

Quizzes can be fun, but it’s a shame that the

rich ecosystem of genres has not been more

fully utilized for botanical games. But there

are exceptions. One of the earliest examples

is SimPark, a simulation game released by

Maxis in 1996. Players manage a park and, in

the process, learn ecological principles and

the natural history of North American plants.

There is even a dichotomous key for plant

(and animal) identification. Now independent

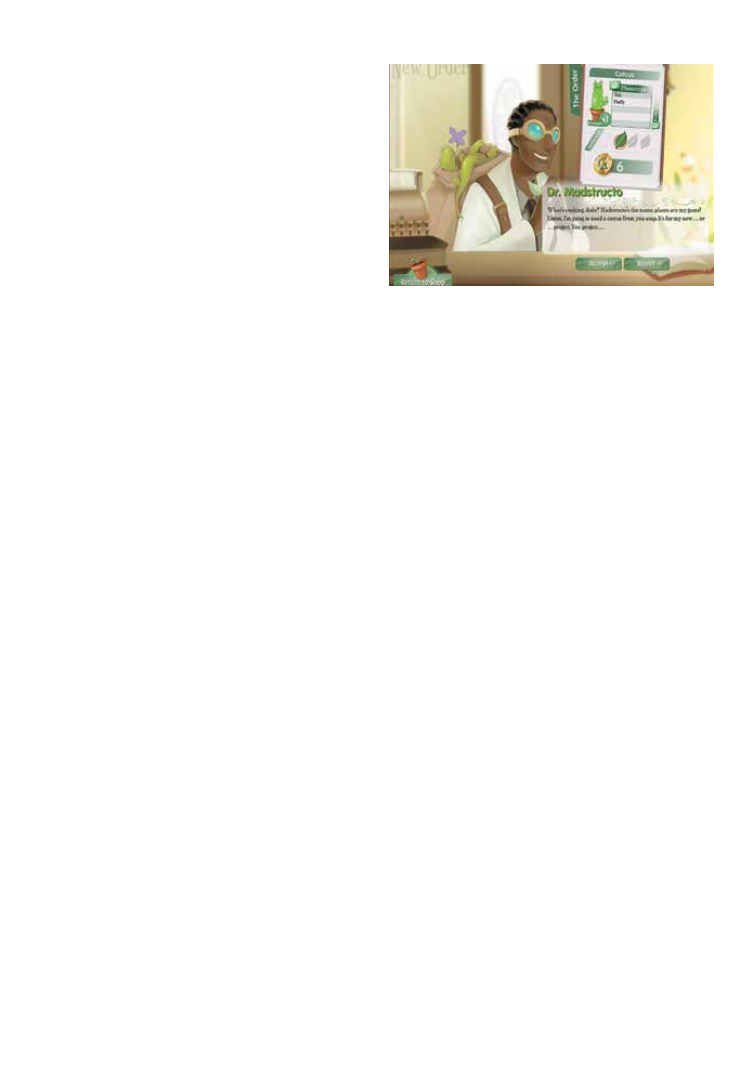

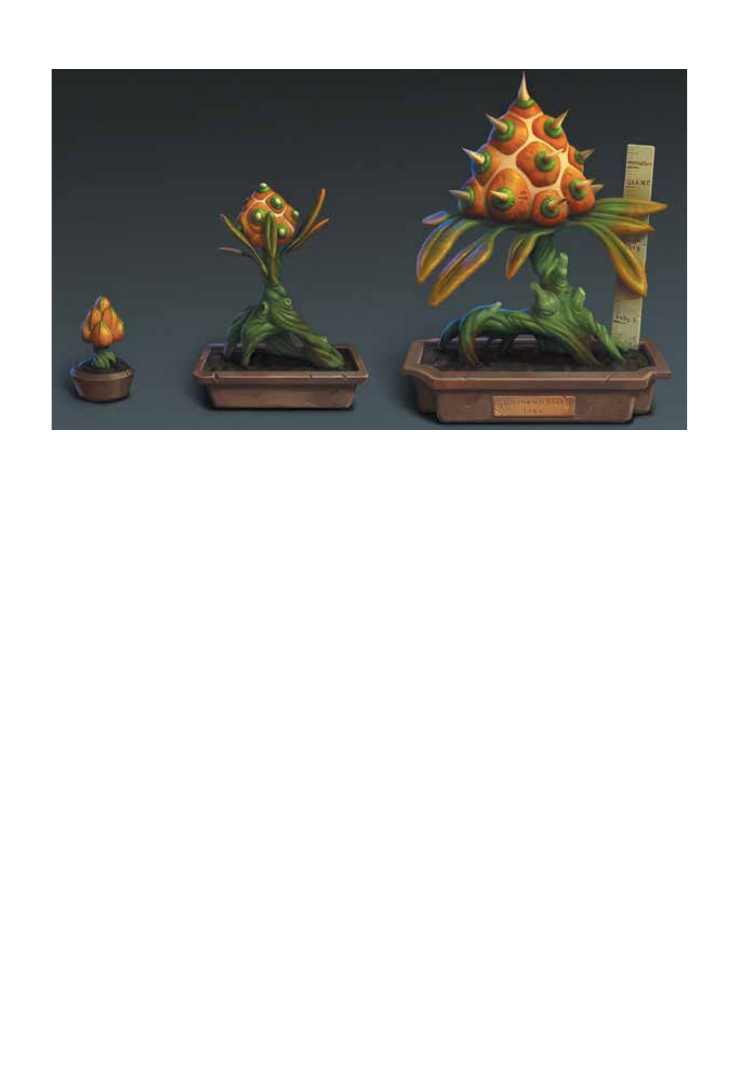

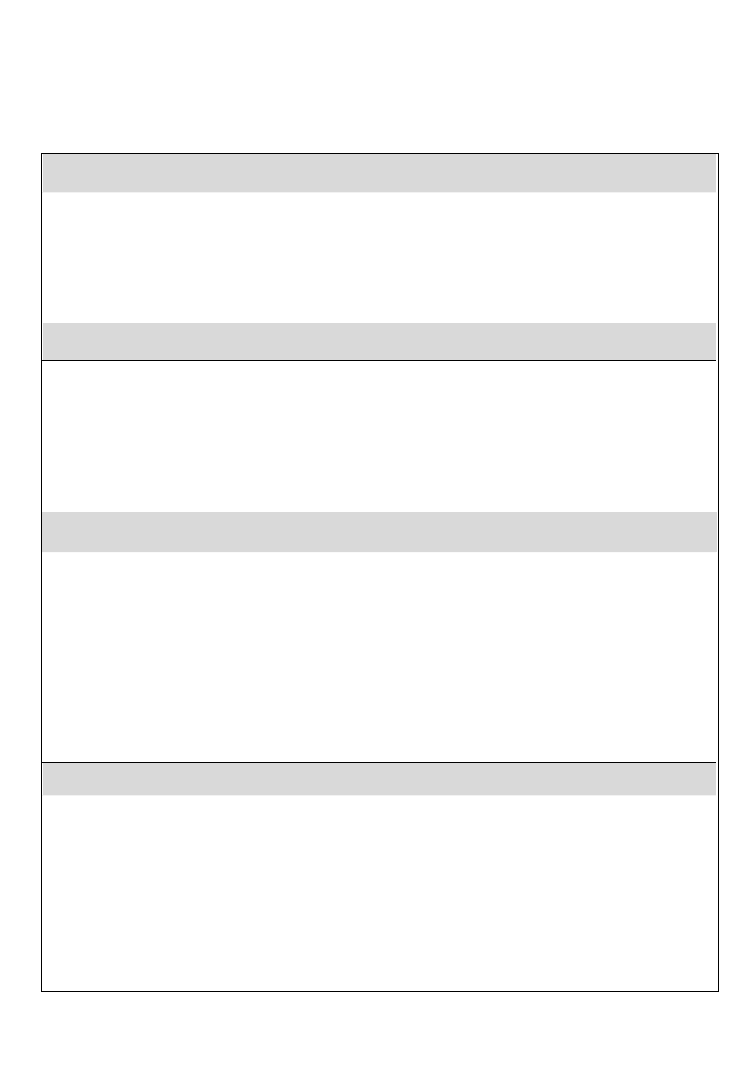

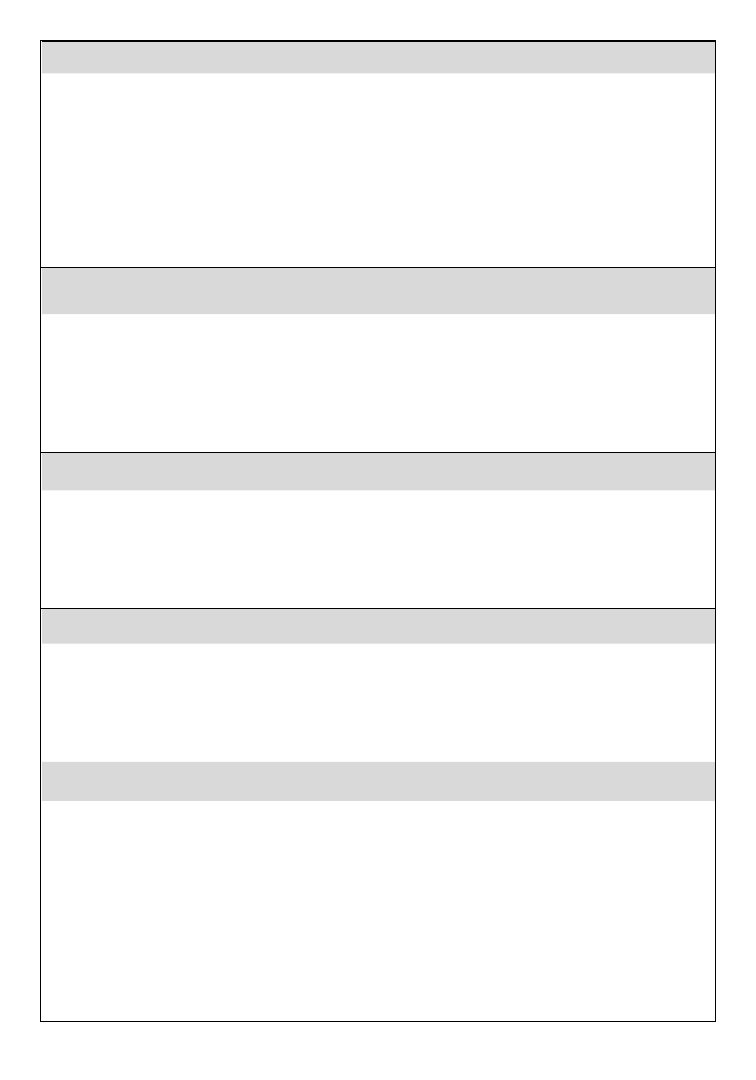

Figure 1. In-game screenshot of a player-creat-

ed garden in Solarium.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

23

studios are beginning to realize the potential.

The casual game Crazy Plant Shop (Figure 2),

by Filament Games, is a clear exception to the

quiz genre, where players learn about genes

and inheritance by breeding zany plants. It

has received 75% positive reviews on Steam,

showing that a well-crafted educational game

can be well received. Another highly interactive

casual game by Filament Games, Reach for the

Sun, teaches plant structures and processes.

Tyto Online is a massively multiplayer online

role-playing game (MMORPG) by Immersed

Games. Although not exclusively about plants,

it has modules about ecology, and growth

and genetics, where the player learns science

concepts through quests and sandboxes

(that is, the player can change his virtual

world at will). Niche, by Stray Fawn Studio,

is an interesting genetics survival game—

unfortunately without a plant component.

But the point is that there are exciting new

initiatives that take full advantage of current

video game technology and trends to teach

biology.

Video games are a remarkable convergence

of artistic and technical creativity—music,

art, 3D graphics, story, environmental design,

characters, and animation to name a few. And

yes, even writing code is a creative process.

Just to make my point, Baba Yetu, a song by

Christopher Tin composed in 2005 as the

theme song for the video game Civilization

IV, by Firaxis Games, won a Grammy

Award for Best Instrumental Arrangement

Accompanying Vocalists. It was the first

piece of music composed for a video game

to win a Grammy. Another example: in 2017,

an 11-minute trailer for the video game

Everything, by David O'Reilly, was the first

video game trailer to qualify for an Academy

Award nomination for Best Animated Short

Film.

But building a video game is a complex and

lengthy journey. It is especially difficult to

make a fun game about science. This is why

scientists and game developers, each with their

own expertise, should work together. This is

already happening with crowd-sourced science

where players help resolve scientific problems

through gameplay. Foldit, an online game

developed by the University of Washington

Center for Game Science in collaboration

with the Department of Biochemistry, has

players (with no biochemistry background)

fold proteins to achieve new structural

configurations, some of which could be used

in the real world. A resulting paper (Cooper

et al., 2010) acknowledged over 57,000 Foldit

players. That must be a first for any science

journal. One interesting approach is to mod

an already existing game. This is what a

team of biochemists and game designers at

the University of Texas, Dallas have done

with Polycraft World (Smaldone, 2017).

Modded from the popular game Minecraft,

by Mojang, players use principles of organic

chemistry to create complex polymers from

simple monomers. Sometimes the scientist

and game developer are one and the same.

Melanie Stegman is a biochemist who studied

the molecular causes of brain cancer, birth

defects, and tuberculosis until she went full-

time into game development. She founded

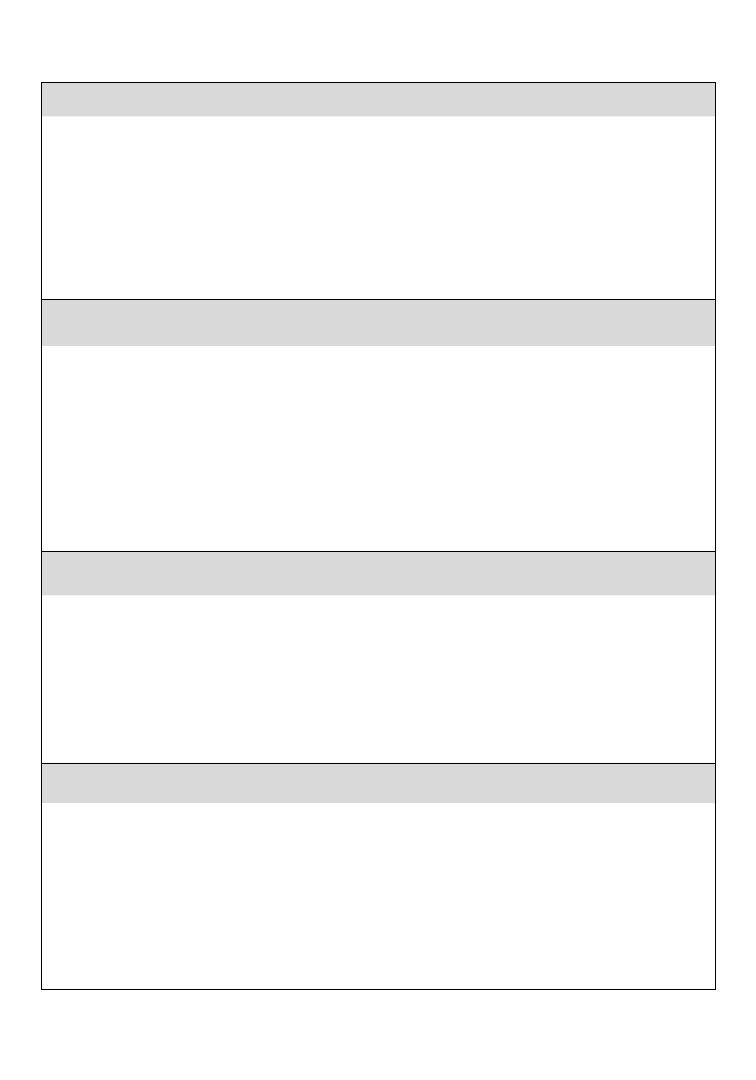

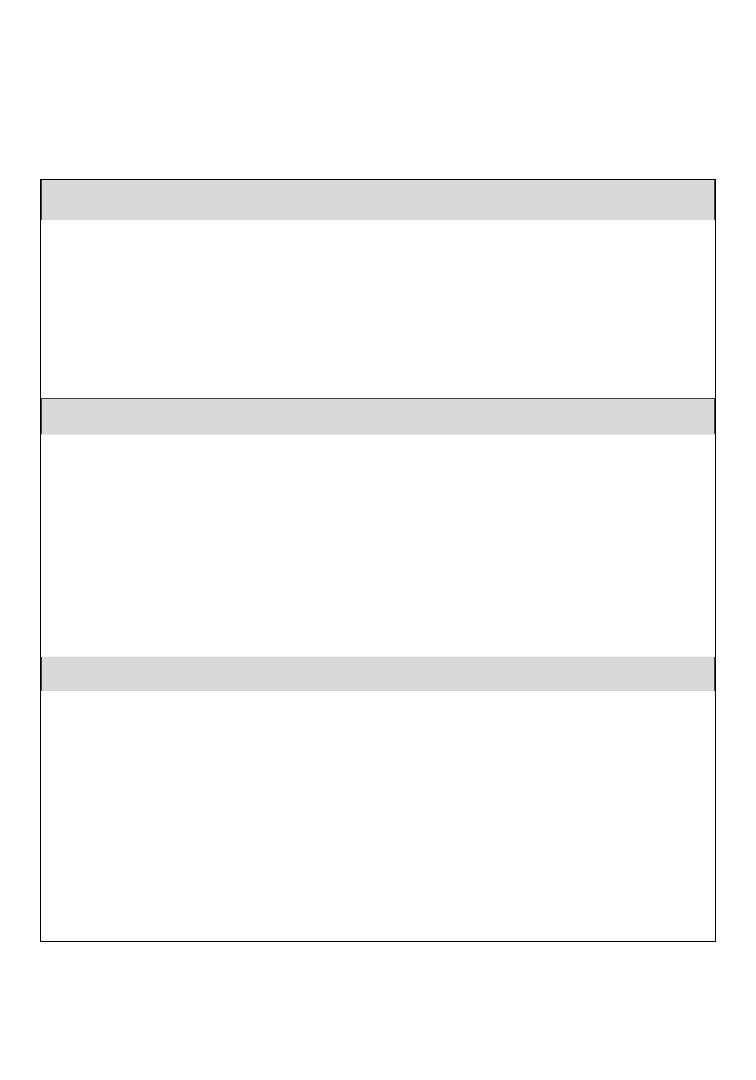

Figure 2. In-game screenshot from Crazy

Plant Shop.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

24

Molecular Jig Games, where she and her team

of scientists and developers make such games

as Immune Defense. Stegman was frustrated

by the fact that when people would ask about

her research, they would not understand the

answers; her mission now is to help those

people understand through games. “When

I talk to people about cells and receptors, I

want them to say ‘Which receptor?’ instead

of ‘What is a receptor?’” She also created

and runs the popular Science Game Center

website (http://www.sciencegamecenter.org/

games) where over 115 science games can

be found. Stegman’s energy and enthusiasm

for making science games is infectious. And

that enthusiasm is becoming more evident

among the growing ranks of scientists who are

morphing into indie game developers (Kwok,

2017).

The number of independently developed

games has exploded in recent years. However,

the process of making and distributing

games is costly. The availability of grants and

new funding models such as online crowd-

funding sites help offset those costs for small

studios, but even so, it is often a struggle,

with game development becoming a labor of

love. Brandon Pittser, Director of Marketing

and Outreach at Filament Games, says,

“Educational game developers face the same

issues as commercial game developers, most

of which can be traced back to funding. In

terms of distributing educational games, the

target customers are often formal educational

environments like schools and libraries, which

tend not to be flush with extra cash.”

Having said that, the market for serious

games (those with a purpose other than pure

entertainment) is growing. According to Eliane

Alhadeff, owner of the Serious Games Market

website (https://www.seriousgamemarket.

com), “In the commercial arena, SG [serious

games] have gone mainstream. The worldwide

educational game market now is in boom

phase. Global, regional, and country market

conditions are now extremely favorable for

Serious Game suppliers.” This is echoed by

Pittser: “A lot of major educational publishers

are now tuned in to the fact that games can take

their existing curricular offerings to the next

level by simply adding some fun, surprise, and

engagement without harming the pedagogical

accuracy and credibility of the product. It’s a

great way to keep students hooked and on-

task with learning content.” Even the popular

game Assassin’s Creed Origins, by Ubisoft

Montréal, has an educational Discovery

Tour edition. And serious games get serious

attention from other quarters as well. There’s

the non-profit Games For Change (G4C)

organization in New York City, whose tagline

says it all: “Empowering game creators and

social innovators to drive real-world impact

through games.” In fact, some of the games

mentioned in this article have won awards at

their annual G4C Festival. And then there’s

BAFTA, the British Academy of Film and

Television Arts, who in 2018 introduced a new

Game Beyond Entertainment category for the

British Academy Games Awards.

But how effective are educational games?

Hundreds of studies have been conducted

on the efficacy of video games in education.

Results seem to vary and likely depend on the

specifics of each game. Efficacy also depends

on evaluation criteria and methodology as

pointed out by Ke (2009), whose metadata

analysis of 89 studies is intended to establish

guidelines and a “best practices” approach

for future studies. To my knowledge, only

one botanical video game has been evaluated

in a classroom setting with the results being

published. The mobile game Little Botany

(Jamonnak and Cheng, 2017) lets players grow

their own plants based on real-time weather

PSB 65 (1) 2019

25

data, anywhere in the world. In so doing,

they learn about plant structure and function

(respiration, photosynthesis, transpiration).

Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from

strongly disagree to strongly agree, player

ratings for various aspects of playability were

high, averaging greater than 4.0.

Here are my suggestions for the elements

needed in a stimulating game about botany:

• First, I’m a real fan of story in a game.

Good examples of adventure games

with strong narratives are Gone Home

and Tacoma (both by The Fullbright

Company), Everybody’s Gone to the

Rapture (The Chinese Room), Firewatch

(Campo Santo), and What Remains of

Edith Finch (Giant Sparrow). As it turns

out, a solid story is important in learning

as it maintains motivation, which is often

a big problem in educational games

(Padilla-Zea et al., 2013).

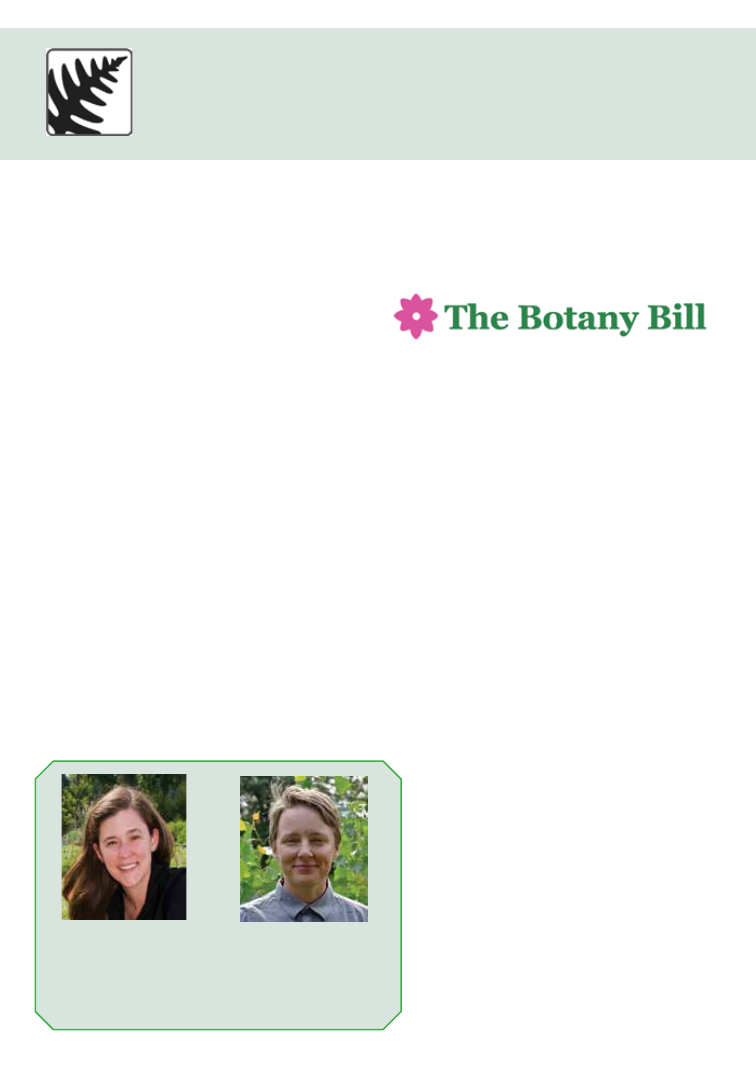

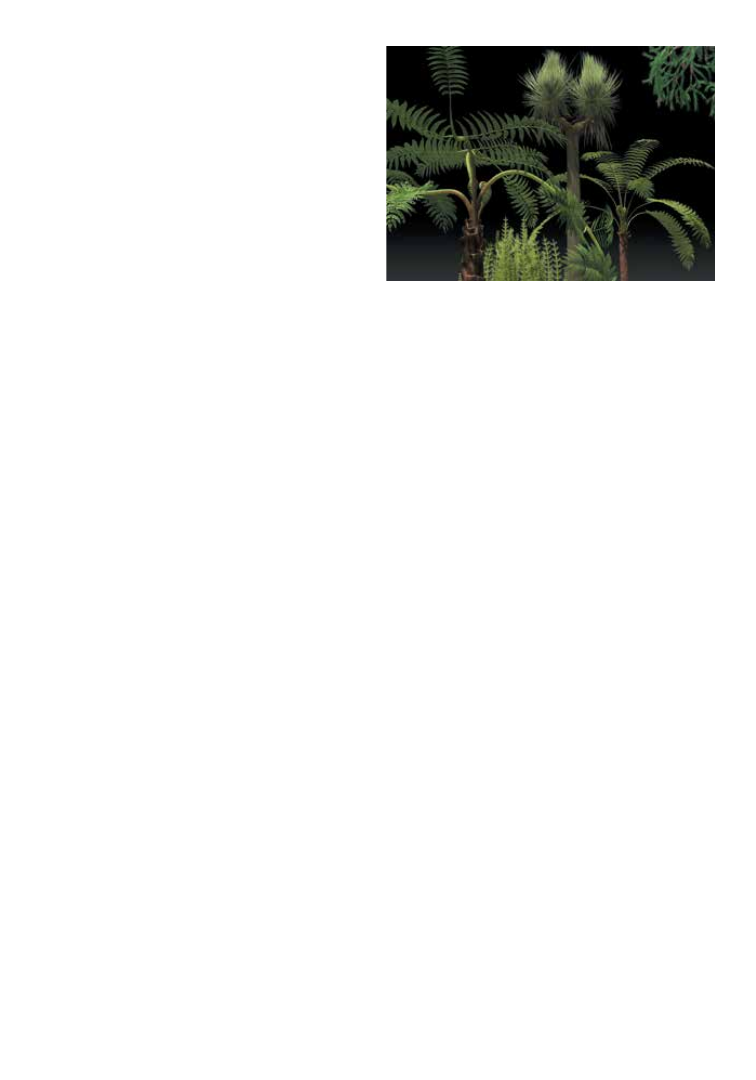

• Next, we need enticing graphics. For

an educational game, this might mean

using botanically accurate 3D models.

But these are not easy to come by and

would likely require custom-crafting.

For example, the stunningly detailed

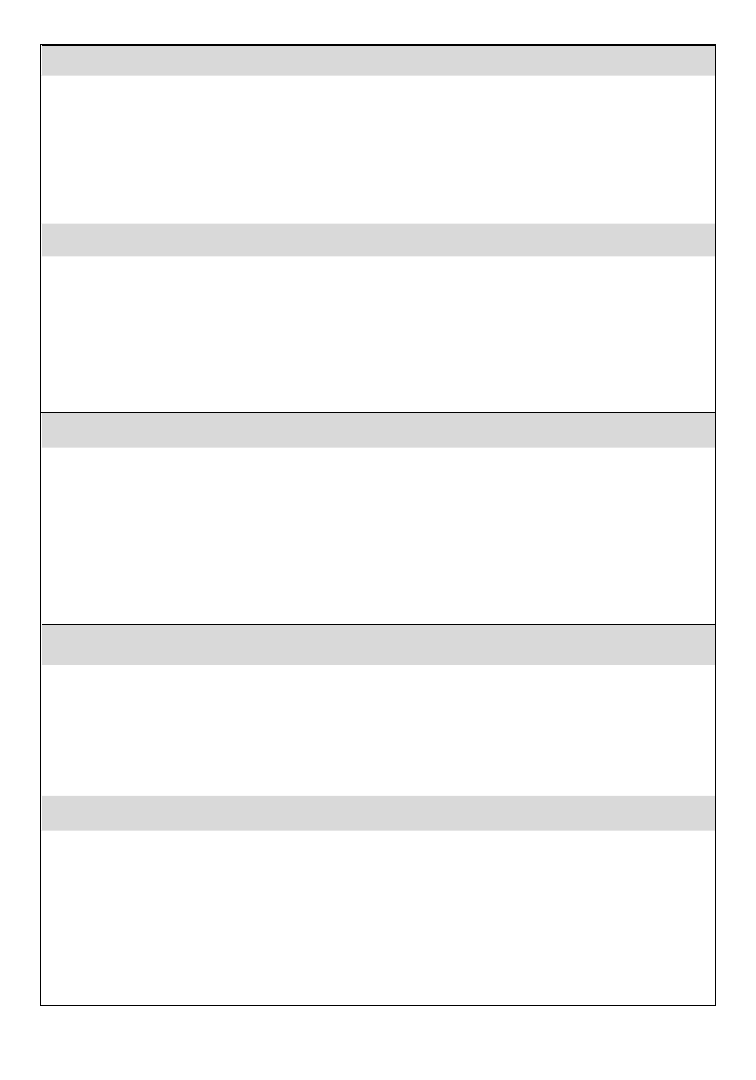

models shown in Figure 3 are the work

of Dariusz Andrulonis, a freelance 3D

artist with a biological background. But

botanical science can also be taught with

imaginative, even cartoon-like, plants. For

example, the whimsical 2D series of plants

in Figure 4 by Olga Samoilova might be

an excellent choice for a platformer game.

It all depends on the mood that the game

creators are trying to achieve.

• We also need a game design that promotes

learning. Although there are many options

here, I like the stealth approach. As one

reviewer of Solarium put it, “They tricked

me into learning.” A good example of that

sort of subtlety is used in the game Never

Alone, by Upper One Games. This puzzle-

platformer shares the stories of Iñupiaq

culture as entertainment, but cleverly

revitalizes interest in Alaskan indigenous

folklore.

So, what would be the story? Being a plant

physiologist with an interest in plant-water

relations, my first thought would be a game

about the adventures of a water molecule. I

think we would need to anthropomorphize

a bit and give the molecule a personality and

a name. So, Emma would wander within the

plant after first entering the root from the soil,

journeying to the leaves through the xylem

and finally departing the plant to join her long-

lost friends in the atmosphere. Along the way,

Emma might help the plant grow by joining

forces with other water molecules to increase

turgor and push mightily on cell walls. Or

she could be recycled from a leaf back to the

roots again through the phloem, carrying

dissolved sugars with her, perhaps frustrating

her to no end. Or maybe she’s torn to bits after

wandering into a chloroplast and being caught

in the process of photosynthesis (very nasty).

We could imagine all kinds of sociological

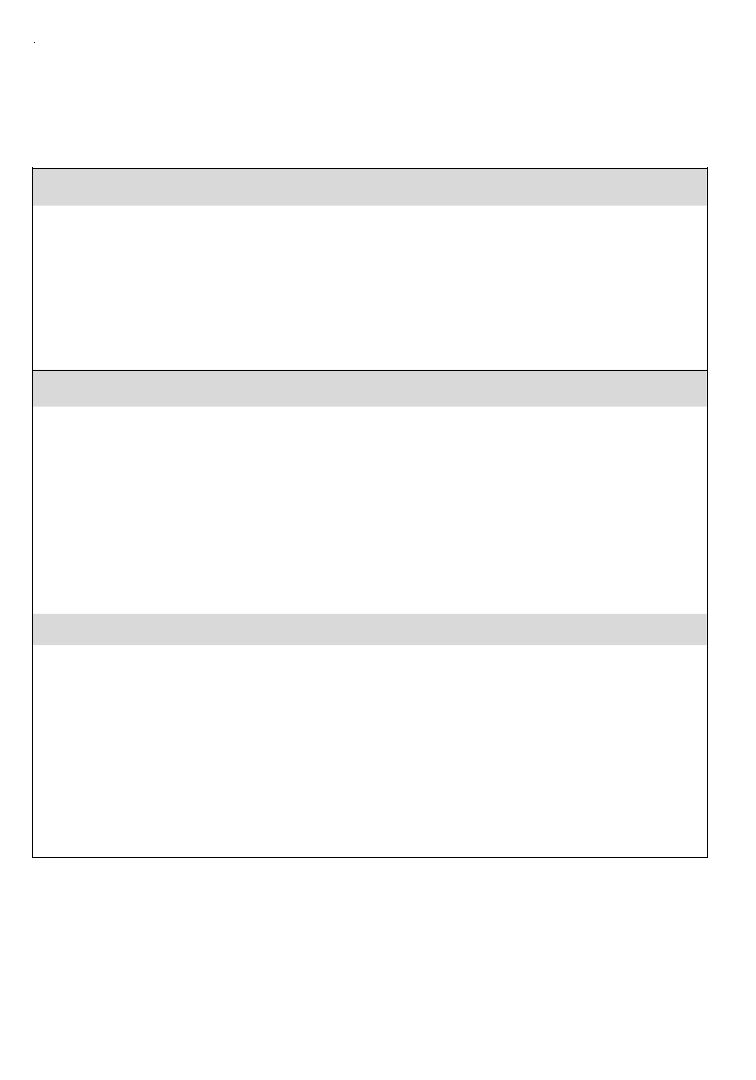

Figure 3. Botanically accurate 3D models of

a Carboniferous forest created by Dariusz An-

drulonis. (https://dariuszandrulonis.artstation.

com/) for the education portal, edukator.pl. The

scene took almost three weeks of intensive work

to complete.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

26

undertones as Emma competes with all those

other water molecules struggling to evaporate

from the interior of the leaf (me first! me first!)

and ultimately gains her freedom through

transpiration.

And here’s the paradox: designing a video

game to be played indoors in order to promote

botany which should take a person outdoors.

One way to bridge that gap is to develop games

which are used exclusively outdoors. For

example, Seek, by iNaturalist, rewards players

with badges for finding examples of plants,

animals, and fungi, using image recognition

technology to identify the player’s uploaded

photographs. For many years, paleontologist

Scott Sampson was the host of Dinosaur Train,

an animated television show teaching children

about prehistoric life and environments

(worth watching even as an adult). He has

always been an advocate for getting out into

nature, yet was part of a show that seemingly

kept kids glued to a screen. In an interview

(Becktold, 2016) about this, Sampson said:

“We’re using technology to leverage nature

connection. If that’s where the eyes are, let’s go

there and promote this thing that’s really good

and important for kids.” I agree.

Video games provide additional ways to

communicate the beautiful science of

plants. The advent of virtual reality (VR)

and augmented reality (AR) will offer

unprecedented opportunity to engage

students and the public in all things botanical.

“The new paradigms of immersion and

interaction provided by these new mediums

creates a new frontier in how we develop and

interact with digital learning content, which is

very exciting,” writes Pittser. And it’s already

happening: Tree, by Milica Zec and Winslow

Porter, is a brilliant new VR project which will

finally give me the chance to see and feel what

it’s like to be a plant. As Stephen Jay Gould

says in his 1993 book, Eight Little Piggies,

“We cannot win this battle to save species and

environments without forging an emotional

bond between ourselves and nature as well—

Figure 4. Fantasy 2D plants created by freelance artist, Olga Samoilova (https://www.artstation.

com/ollsamoilova). The drawing took 64 hours to complete.

PSB 65 (1) 2019

27

for we will not fight to save what we do not

love.” My hope is that the power of video

games will ignite in others the same love of

plants that was ignited in that 10-year-old boy

in his garden so many years ago.

LITERATURE CITED

Becktold, W. 2016. In Conversation with Dinosaur

Train’s Scott Sampson. Sierra, The national maga-

zine of the Sierra Club. https://www.sierraclub.org/

sierra/2016-5-september-october/mixed-media/

conversation-dinosaur-train-s-scott-sampson. Ac-

cessed August 30, 2018.

Blackhall-Miles, R. 2015. We need a cure for plant

blindness. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.

com/lifeandstyle/gardening-blog/2015/sep/17/we-

need-a-cure-for-plant-blindness. Accessed October

10, 2018.

Cooper, S., Khatib, F., Treuille, A., Barbero, J., Lee,

J., Beenen, M., Leaver-Fay, A., Baker, D., Popović,

Z., and Foldit players. 2010. Predicting protein

structures with a multiplayer online game. Nature

466: 756–760.

Cowley, B., Charles, D., Black, M., and Hickey, R.

2008. Toward an understanding of flow in video

games. Computers in Entertainment 6(2): Article 20.

Csíkszentmihályi, M. 1975. Beyond Boredom and

Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play, San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-87589-261-2

Dugan, F. M. 2016. Shakespeare, Plant Blindness

and Electronic Media. Plant Science Bulletin 62: 85-92.

ESA, 2018. http://www.theesa.com/about-esa/in-

dustry-facts/. Accessed October 10, 2018.

Higgins, A. 2018. The horticulture industry’s age

problem is bigger than you think. Washington Post.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/home/

the-horticulture-industrys-age-problem-is-bigger-

than-you-think/2018/08/05/3c7d3618-734f-11e8-8

05c-4b67019fcfe4_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_

term=.c6f36926f02a.

Jamonnak, S. and Cheng, E. 2017. Little Botany: A

mobile game utilizing data integration to enhance

plant science education. International Journal of

Computer Games Technology. Article ID 3635061.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3635061