IN THIS ISSUE...

FALL 2018 VOLUME 64 NUMBER 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Theresa Culley on publishing tips for

junior researchers...p.167

Get to know new BSA student rep,

Min Ya....p. 192

Meet Amelia Neely, BSA’s new member-

ship/communications manager...p. 147

PLANTS Grant Fellows and Mentors at BOTANY 2018

Fall 2018 Volume 64 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 64

From the Editor

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Environmental Sciences

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22904

kal8d@virginia.edu

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

melanie.link-perez

@oregonstate.edu

Shannon Fehlberg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

Greetings,

Happy autumn to all in the northern hemi-

sphere. The fall of leaves means that, in the

United States, we are drawing close to a crit-

ical mid-term election. It is hard for me to

forget this since I am bombarded by cam-

paign ads from both Iowa and Nebraska. We

all know that elected officials have a tremen-

dous impact on scientific research and on

how science is incorporated into public poli-

cy. Yet, it can be overwhelming to attempt to

effect change as a citizen, especially in a time

when there are so many pressing politicized

issues.

In this issue, the public policy committee sets

out a framework for participating in civic life

as a scientist that we hope you will find useful.

We also present an article from the winners

of the 2018 Botanical Advocacy Leadership

Award. This important award provides fund-

ing to support local efforts that contribute

to shaping public policy. For a more histor-

ical perspective, we bring you remarks from

BSA President-Elect Dr. Andrea Wolfe, who

surveyed science policy under the last four

presidential administrations as evidenced by

newspaper articles and discusses why science

really does matter. I hope that you find these

articles both educational and inspirational!

Cheers,

135

SOCIETY NEWS

We live in a technological era where information

can be used, abused, misinterpreted, and virally

shared for presenting ideological viewpoints

without regard to accuracy of content. When

this involves science and government policy,

the potential for major consequences to the

environment, society, scientists, and future

generations exists.

Several years ago, I started using Merchants

of Doubt (Oreskes and Conway, 2010) for a

supplemental textbook in my “Society and

Evolution” course. The subtitle for this book

is “How a handful of scientists obscured

the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to

global warming.” The book describes how a

small number of scientists could be used by

political entities to misrepresent the majority

opinion of other scientists with regards to the

causes and environmental impacts of acid

rain, atmospheric ozone holes, global climate

change, as well as the health effects of tobacco

use and environmental consequences of

pesticide use. What struck me as particularly

By Andrea Wolfe

The Ohio State University

Department of

Evolution, Ecology, and

Organismal Biology

E-mail: wolfe.205@osu.

edu

Science—It Really Does Matter

Remarks from BOTANY 2018

by President-Elect Andi Wolfe

dangerous was how politicians and political

lobbyists use small bits of scientific studies

that agree with their ideological viewpoints to

influence public policy that may affect several

generations after regulations are enacted or

rescinded.

My “Society and Evolution” course focuses on

trying to understand why some populations

of the USA are anti-evolution and, in general,

anti-science. My students do several research

projects where they mine databases to look at

trends of acceptance or denial of evolution,

based on stories covered in local, regional,

national, and international newspapers. One

of the outcomes of these projects is a better

understanding of the role of religion and

politics in science education and science

literacy.

The newspaper databases offer one a chance

to see general trends about a society’s reaction

to specific opinions, policy, and scientific

research. Thus, I found myself turning to

newspaper archives when I decided to talk

about why science matters in society. I wanted

to investigate how government leadership

can affect science policy and debate, and I

was interested in seeing how government

policies impact scientific research and science

education. Also, I was curious about how

political biases may have an impact on science

literacy, and how this might affect efforts for

science communication.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

136

How government leadership

impacts scientific research

and debate

My focus was on the most recent U.S.

administrations, straddling the end of the

20th- and into the 21st-century. This included

the administrations of Bill Clinton (1993-

2001), George W. Bush (2001-2009), Barack

Obama (2009-2017), and Donald J. Trump

(2017-current). I searched the Newspaper

Source database with the following

words in the all-text mode: science (and)

president’s name (and) policy. The number

of articles returned ranged from 756 (Trump

administration, covering 1.5 yr) to 1,974 (Bill

Clinton administration); there were 1,319 and

1,564 articles returned for Obama and Bush,

respectively. Not all of the articles referred

to science policy, but there was a sufficient

number of articles with repeated themes to

take the pulse of an administration’s attitude

about science, and the role of science in

administrative policy.

Headlines from each administration are listed

in Table 1, along with either quotes from,

or notes about, the article. There are very

clear trends regarding an administration’s

attitude about science, and the effect it has

on policy decisions. First, from 1993 to 2018,

administrations with a Democrat as president

were pro-science, pro-environment, and used

advice from scientists before making decisions

about policy. For example, Clinton expanded

wilderness areas and enacted environmental

protections aimed at reducing pollution and

greenhouse gas emissions. Clinton was also

concerned about the declining test scores for

U.S. high school students on standardized

tests for math and science. Obama started

his administration by recruiting well-

known scientists to fill cabinet positions for

departments that need science expertise. He

also implemented strategies for increasing

funding for science, reducing the nation’s

need for fossil fuels, enforcing environmental

regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, and

releasing restrictions on scientific research

that were based on conservative ideology.

In contrast, both Republican presidents

during this period had a pattern of

ignoring or misusing science, reducing

funding for basic research, and rolling back

environmental regulations to benefit the fossil

fuel energy industry. Under both Republican

administrations, climate change denial was

systematic throughout federal agencies.

The Bush administration focused its efforts

for science research on homeland security,

and implemented restrictions on science

research that offended the conservative right

population. This had impacts on basic research

in that scientists had restrictions about who

could work with them, what topics could be

studied, and how, or if, scientific results could

be disseminated. Trump’s administration is

anti-science, and this is reflected in the sheer

number of articles that address his “war on

science,” his campaign to turn public lands

into opportunities for businesses to exploit,

and his enabling the federal government,

particularly science and environmental

agencies, to implode due to mismanagement.

The role of government in

scientific research and

science education

Given the above information about the major

differences the political party of a president

has on American science, I wanted to know if

the government has a role in scientific research

PSB 64 (3) 2018

137

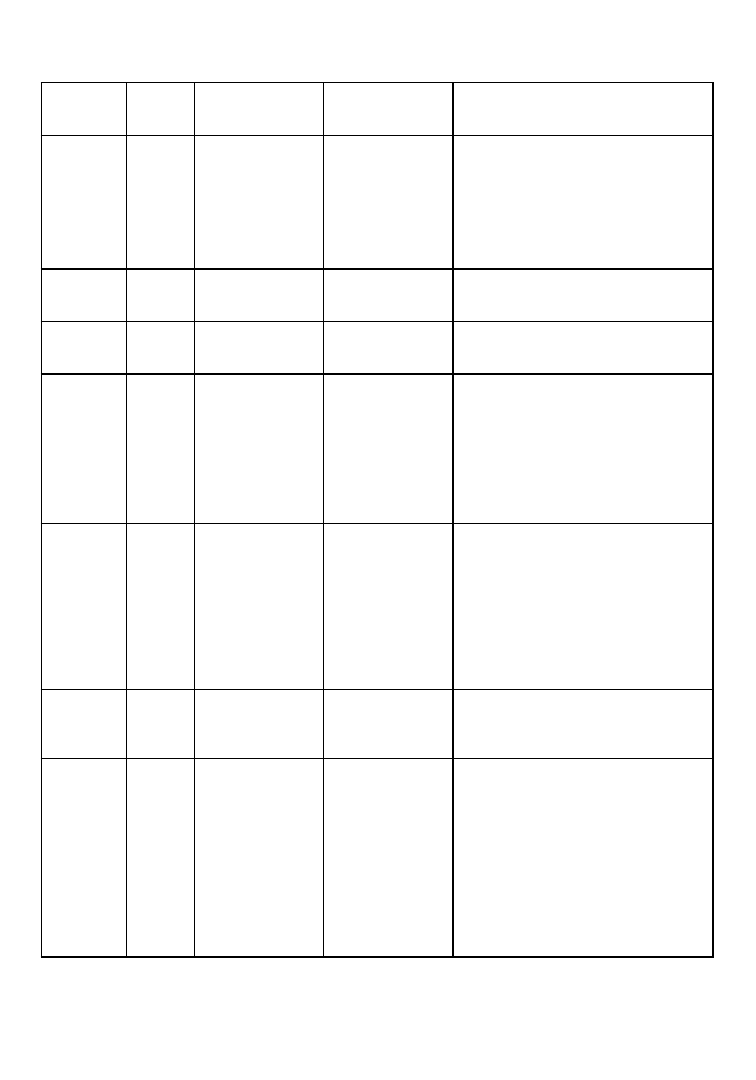

President

Date(s) Headline

Publication

Notes

Bill Clinton

(Democrat) 1993-2001

03/08/1995

Endangered Species

Act faces its own dan-

gers

Christian Science

Monitor

The recently formed Senate Republican Regu-

latory Relief Task Force put the ESA at the top

of its “Top Ten Worst-Case Regulations.”

05/19/1995

The GOP needs a bit

more R&D on its sci-

ence and technology

policy

The Washington Post

Congress had made a point to change the bud-

get submitted by Clinton to reduce spending

efforts on science.

07/04/1995 A Department of Sci-

ence?

The Washington Post

This was an attempt by Republicans to con-

solidate NASA, NSF, EPA, USGS, NOAA, the

Patent & Trademark Office, and research arms

of the Energy and Commerce Departments.

It would have changed funding for each of

the agencies, with major impacts on basic re-

search. The initiative failed.

09/07/1995

Alaska becomes test

of wills on Federal

land policy

Christian Science

Monitor

This was about how a Republican-led Congress

attempted to open the Arctic National Wild-

life Refuge and Tongass National Forest to oil

drilling.

02/19/1997 States feud with EPA

Christian Science

Monitor

“After giving states more power to protect

clean air and water, the Clinton administration

is threatening to take back such controls be-

cause of concerns that, in some states at least,

devolution means more pollution.” The EPA

argued that state laws for pollution were too

lax. Ironically, it was Michigan that was fight-

ing Federal oversight.

10/30/1997 Greenhouse gas plan

faces GOP red light

Christian Science

Monitor

Clinton’s proposals for international action

to combat global warming were considered

too lax by environmentalists and Europeans,

but too strict by Republicans because the link

between greenhouse gas emission and global

warming “is not firmly established.”

03/17/1998 Clinton proposes test-

ing

New York Times

High school seniors were performing poorly

on standardized math and science tests. Clin-

ton proposed testing high school teachers to

prove competency prior to receiving a teach-

ing license.

06/15/1999

Clinton plan hopes to

reassert the value of

‘wilderness’

Christian Science

Monitor

Clinton was trying to set aside five million

acres of national park land as wilderness, pri-

marily to prevent development.

11/15/2000

In last days, Clinton

begins environmental

offensive

Christian Science

Monitor

Clinton ordered one-third of America’s na-

tional forests to be made off limits to logging,

mining, and road-building.

George W.

Bush (Repub-

lican)

2001-2009

04/20/2001 Bush walks fine line

on ecology

Christian Science

Monitor

Critics of Bush’s appointments and early deci-

sions on global warming and endangered spe-

cies policies state that Bush “has declared war

on the environment.”

Table 1. Headlines about science and policy from the past four administrations in the United States.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

138

06/17/2001

Sure, it’s rocket sci-

ence, but who needs

scientists?

New York Times

“Indeed, some experts believe that science’s in-

fluence in public policy matters has not been at

such a low ebb since before World War I.”

07/24/2001

Researchers forecast

rapid, irreversible cli-

mate warming

Environmental News

Network

“The United States signed the Kyoto Protocol

under the Clinton administration, but Pres-

ident George W. Bush announced in March

that the United States would not ratify the

treaty. This move caused a crisis in the inter-

national approach to the agreement since the

United States emits 25 percent of the world’s

heat-trapping greenhouse gases.”

08/02/2001 As House votes on en-

ergy plan, oil booms

Christian Science

Monitor

“The House expects to vote on Bush’s initia-

tive—which stresses boosting production—by

the end of the week.”

11/05/2001

Science a proven tool

in ensuring homeland

security

The Dallas Morning

News

The attitude toward science changed after 9/11,

but only with regard to homeland security.

11/27/2001

Scientists ponder lim-

its on access to germ

research

New York Times

In response to 9/11, and concerns about bio-

terrorism, there were proposals to restrict ac-

cess to information and materials that might

be used for biological weapons.

“Already several proposals have been made in

Congress to forbid some people, including cer-

tain foreigners, from working in laboratories

that handle dangerous microbes.”

10/19/2002

Researchers say sci-

ence is hurt by secre-

cy policy set up by the

White House

New York Times

“The presidents of the National Academies

said yesterday that the Bush administration

was going too far in limiting publication of

some scientific research out of concern that it

could aid terrorists…Specifically, they said, the

administration’s policy of restricting publica-

tion of federally financed research it deemed

‘sensitive but unclassified’ threatened to ‘stifle

scientific creativity and to weaken national se-

curity.’”

12/06/2002

Now, science panelists

are picked for ideolo-

gy rather than exper-

tise

Wall Street Journal

Scientific advisory panelists for federal agen-

cies was controversial due to selection of can-

didates with conservative ideologies rather

than on their skills or experience.

07/08/2003

Policy as arcade game:

when science crosses

Bush agenda, it takes

a beating

The Philadelphia

Inquirer

“President Bush is playing Whack-a-Mole

with scientific reports that he doesn’t like: Un-

comfortable facts about global warming pop

up in an environmental report card. Whack!

Yellowstone National Park staffers tell a world

treasures watchdog that the park is in trouble.

Whack! The Environmental Protection Agen-

cy discovers a senator’s clean air bill is more

effective than the president’s. Whack! But the

moles are popping up faster than the Bush

team can beat them back. Information is leak-

ing out. A pattern of deception is emerging.”

PSB 64 (3) 2018

139

02/23/2004 Uses and abuses of

Science

New York Times

“Although the Bush administration is hardly

the first to politicize science, no administra-

tion in recent memory has so shamelessly dis-

torted scientific findings for policy reasons or

suppressed them when they conflict with polit-

ical goals.” This was from an indictment deliv-

ered by >60 prominent scientists, including 20

Nobel laureates.

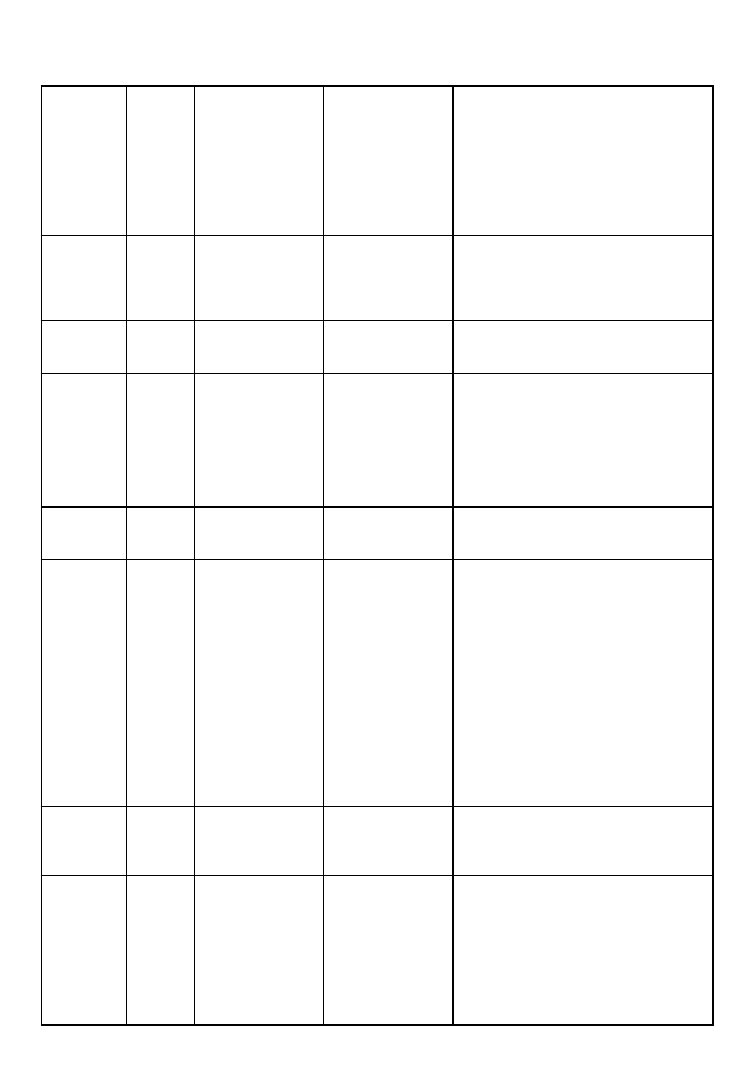

Barack Obama

(Democrat) 2009-2017

01/14/2009 EPA nominee vows to

rely on science

USA Today

Obama began his administration by filling his

cabinet with qualified individuals.

01/20/2009

Boulder, Colo.

area scientists cheer

Obama

Daily Camera

“After eight years of pervasive political med-

dling in science, according to the Union of

Concerned Scientists, researchers in Boulder

are cheering Barack Obama, who has prom-

ised to return integrity to U.S. science policy…

Obama has promised to double federal invest-

ment in basic research, and he has nominated

distinguished researchers for key positions,

such as tapping Nobel Prize-winning physicist

Steven Chu for secretary of energy.”

01/27/2009 Elevating science, ele-

vating democracy.

New York Times

Essay by science editor Dennis Overbye: analy-

zing Obama’s inaugural speech, where Obama

proclaimed that he would “restore science to

its rightful place.” The president also vowed to

harness technology for clean energy.

01/28/2009

Climate expert says

global warming will

be major priority of

Obama Presidency

Irish Times

Mentions Obama’s appointment of experts to

his cabinet, and vows to prioritize clean energy

initiatives.

02/26/2009

A d m i n i s t r a t i o n

tasked with undoing

Bush-era policies on

air quality

The Press-Enterprise

“Less than six weeks after George W. Bush left

office, clean-air advocates are wasting no time

under the new administration to push for new

and tougher regulations. Several of the former

president’s air pollution policies already are in

jeopardy, raising hopes among clean-air advo-

cates and fears among those who worry that

industries could get hit with higher costs du-

ring a recession.”

03/10/2009

Editorial: Finally: The

right approach to sci-

ence

Obama puts his own

spin on the mix of sci-

ence with politics

La Crosse Tribune

New York Times

Reports on Obama’s efforts to have policies

built on science rather than ideology. This was

specifically in reference to rolling back the

regulations on embryonic stem cell research

from the Bush administration.

07/20/2009 Mo. Lawmaker battles

Obama agenda

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“In his first months in office, [Blaine] Luetke-

meyer, R-St. Elizabeth, has established himself

as an unwavering conservative, a budget hawk,

and a critic of global warming theories who is

so certain in his beliefs that he accuses Nobel

Prize winners of ‘junk science.’”

PSB 64 (3) 2018

140

12/28/2010

Science bill could

bring federal money

to the Valley

The Monitor

“A relatively unknown bill affecting science

education and job creation won overwhelm-

ing approval in the U.S. Congress before it re-

cessed, and could energize science-related op-

portunities in South Texas.” This was referring

to the America Competes Reauthorization Act

(ACRA), which had unanimous approval in

the Senate and was approved at 228-130 in the

House of Representatives.

11/19/2012 Rubio: ‘I’m not a sci-

entist’

GQ Magazine

This was one of many stories during the Obama

administration about Republican politicians

making a statement about their lack of scien-

tific literacy, and that their decisions about sci-

ence policy were based on other factors.

05/14/2014

All science is wrong,

concludes esteemed

Fox News panel

New York Magazine This was an article about partisan pushback on

science.

05/30/2014

Why do Republicans

always say ‘I’m not a

scientist’?

New York Magazine

“’I’m not a scientist’ allows Republicans to

avoid conceding the legitimacy of climate sci-

ence while also avoiding the political downside

of openly branding themselves as haters of sci-

ence. The beauty of the line is that it implicitly

concedes that scientists possess real expertise,

while simultaneously allowing you to ignore

that expertise altogether.”

Donald J.

Trump (Re-

publican)

2017-cur-

rent

11/19/2016

Climate change in

Trump’s age of igno-

rance

New York Times

“We now live in a world where ignorance of a

very dangerous sort is being deliberately man-

ufactured, to protect certain kinds of unfet-

tered corporate enterprise. The global climate

catastrophe gets short shrift, largely because

powerful fossil fuel producers still have enor-

mous political clout, following decades-long

campaigns to sow doubt about whether an-

thropogenic emissions are really causing plan-

etary warming. Trust in science suffers, but

also trust in government. And that is not an

accident. Climate deniers are not so much an-

ti-science as anti-regulation and anti-govern-

ment.”

11/30/2016

Trump administra-

tion’s climate-change

skeptics worry re-

searchers, advocates

KUAC FM radio

“There’s growing concern among the scientif-

ic community that President-elect Trump will

reduce or eliminate support and funding for

studying climate change.”

01/19/2017

03/12/2017

Rogue scientists race

to save climate data

from Trump

California scientists

worry that Trump will

interfere with climate

data

Science

The San Diego

Union-Tribune

Report on how scientists were saving climate

change databases under threat from Trump’s

policies at government agencies such as EPA,

US Department of Interior, and others.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

141

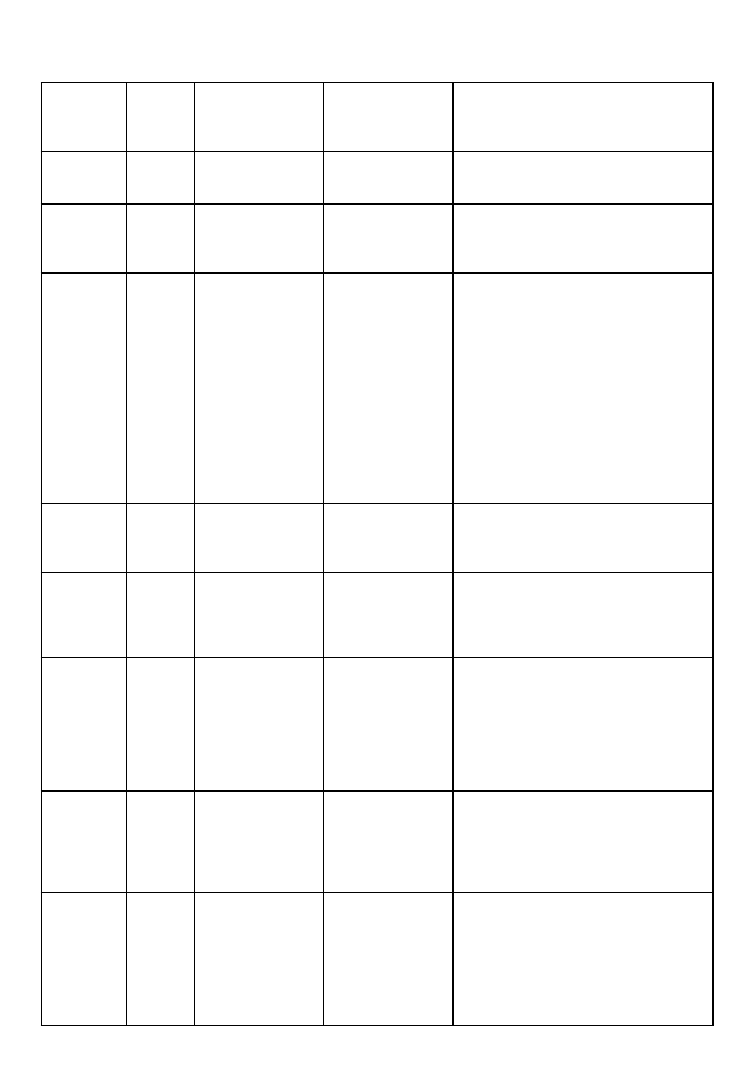

01/31/2017

Science will suffer un-

der administration’s

travel ban, officials

say.

New York Times

Discusses the potential impact of Trump’s trav-

el ban on people from certain countries.

01/31/2017

Why science matters

more than ever in

Trump’s America

Forbes Magazine

“It may be the only way to save the USA—and

the world—from alternative facts.”

03/03/2017

Trump plan for 40%

cut could cause EPA

science office ‘to im-

plode,’ official warns

Science

A response to cuts in program funding at EPA.

03/20/2017

03/27/2017

08/17/2017

Research is an af-

terthought in first

Trump budget

The Trump Adminis-

tration’s War on Sci-

ence

Trump’s first list of

science priorities ig-

nores climate—and

departs from his own

budget request

Science

New York Times

Science

Trump’s initial budget either made cuts or flat-

lined federal spending on science research

04/22/2017

March for Science:

Protesters gather

worldwide to support

‘evidence’

CNN

A global response to the disregard for science,

and the promotion of “alternative facts.”

05/08/2017

At FDA, TVs now

turned to Fox News

and can’t be switched

CBS News

“CBS News has confirmed an email was sent

to researchers at the FDA’s Center for Biologics

Evaluation and Research responding to appar-

ent efforts to change the channel on internal

television screens.”

05/28/2017

Editorial: Trump ap-

pointees twist facts,

deny science

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“President Donald Trump has named two

prominent anti-abortion activists and LGBT-

rights opponents to influential positions in the

Department of Health and Human Services,

but those views aren’t what should trouble

Americans most. What is very disturbing is

that each appointee openly denies science and

facts.”

06/06/2017

85 percent of the

top science jobs in

Trump’s government

don’t even have a

nominee

The Washington Post

This trend continued up until the time of my

BOTANY 2018 talk. The only agencies with a

complete complement of scientists more than

a year later from the publication date of this

article were Education and Nuclear Regulatory

Commission.

06/28/2017

Trump will try to

sidestep science in

rolling back clean wa-

ter rule

Science

Rules enacted during the last months of a pres-

ident’s term are subject to being overturned by

the next president’s administration. Whereas

Obama’s administration relied on scientific

findings for implementing regulations, the

Trump administration was catering to the

fossil fuel industry—specifically, coal—for re-

scinding this rule.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

142

07/01/2017

10/31/2017

12/05/2017

07/10/2018

EPA chief pushing

government-wide

effort to question cli-

mate change science.

Trump’s EPA has

blocked agency grant-

ees from serving on

science advisory pan-

els.

Accumulating evi-

dence: Federal scien-

tists are being silenced

DOI restricts scien-

tists from attending

scientific conferences

The Washington Post

Science

Union of Concerned

Scientists

Union of Concerned

Scientists

Climate change information was removed

from the EPA and other agency websites,

memos stating rules about not using specific

terminology had been circulated, and regula-

tions were being rolled back concerning green-

house gas emissions. Scientists were prevented

from conducting research, attending meetings,

and serving on expert panels

07/11/2017

07/20/2017

09/01/2017

12/05/2017

04/17/2018

Trump nominates fi-

nance executive for

DOE science under-

secretary

Trump picks climate

change doubter for

USDA science job

Trump has picked

a politician to lead

NASA. Is that a good

thing?

Trump science job

nominees missing

advanced science de-

grees

Ryan Zinke refers to

himself as a geologist.

That’s a job he’s never

held.

Science

The Hill

Science

Associated Press

CNN

Cabinet positions requiring science literacy in

the Trump administration were filled by non-

or under-qualified personnel. This list includ-

ed Rick Perry, a previous presidential election

candidate who had wanted to disband the De-

partment of Energy. Trump appointed Perry to

lead that agency.

07/17/2017 Sidelining science

since day one

Union of Concerned

Scientists

“The Trump presidency has shown a clear pat-

tern of actions that threaten public health and

safety by eroding the role of science in policy.”

08/09/2017

The battle over sci-

ence in the Trump

administration

CNN

“Scientists allege policies of ‘myth over truth’

under Trump.”

12/14/2017

A year of Trump: Sci-

ence is a major casual-

ty in the new politics

of disruption

Scientific American

“From a rollback of environmental protections

to attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act,

here’s a look at the president’s impact on sci-

ence-related issues.”

12/26/2017

‘Junk science’? Studies

behind Obama regu-

lations under fire

Fox News

“The federal report by dozens of U.S. govern-

ment scientists concludes climate change is

real and is driven almost exclusively by human

activity.”

PSB 64 (3) 2018

143

01/01/2018

The Trump adminis-

tration’s war on sci-

ence agencies threat-

ens the nation’s health

and safety

Scientific American

“Budget cuts and layoffs threaten the nation’s

health and safety.”

01/09/2018

U.S. Interior Depart-

ment to put academ-

ic, nonprofit grants

through political re-

view

Science

Grants provided by DOI to receive scrutiny to

“ensure they align with Trump administration

policies.”

01/16/2009

Citing ‘inexcusable’

treatment, advisors

quit National Parks

Panel

New York Times

The advisory panel was formed in 1935. The

majority resigned in protests of Ryan Zinke’s

plans to open protected areas to oil drilling and

mining.

01/18/2018

Trump administra-

tion is ‘abandoning

science,’ scientists

claim

Newsweek

“The White House has been sidelining ad-

vice from scientific advisory councils sin-

ce President Donald Trump took office in

January 2017, according to a new analysis

released Thursday…The report titled ‘Aban-

doning Science Advice’ by the nonprofit ad-

vocacy organization Union of Concerned

Scientists found that science advisory commit-

tees had experienced ‘unprecedented’ levels of

disrespect and neglect from the White House

and across agencies including the Environ-

mental Protection Agency, the Food and Drug

Administration and the Department of Ener-

gy.”

01/22/2018

06/06/2018

07/19/2018

The damage done by

Trump’s Department

of the Interior

Ryan Zinke is sabo-

taging our best public

lands program

Interior Department

proposes a vast re-

working of the En-

dangered Species Act

The New Yorker

Outside Magazine

New York Times

“Under Ryan Zinke, the Secretary of the Interi-

or, it’s a sell-off from sea to shining sea.”

“The secretary of the interior was once a loud

supporter of the Land and Water Conservati-

on Fund. Now he wants to almost completely

defund it.”

“The changes are in keeping with a broader

pattern of regulatory moves in the Trump ad-

ministration aimed at reducing costs and other

burdens for business, particularly the energy

business.”

03/23/2018

Congress ignores

Trump’s priorities for

science funding

The Atlantic

“Nearly every science agency stands to get

more money under a spending bill that avoids

proposed cuts from the White House.”

05/23/2018

Internal memo sug-

gested that White

House ‘ignore’ federal

scientists’ climate re-

search.

The Washington Post Refers to the report published the previous

year.

06/09/2018

In the Trump admin-

istration, science is

unwelcome. So is ad-

vice.

New York Times

“As the president prepares for nuclear talks, he

lacks a close adviser with nuclear expertise. It’s

one example of a marginalization of science in

shaping federal policy.”

PSB 64 (3) 2018

144

beyond funding and policy. I researched the

U.S. government websites, and data from the

U.S. Bureau of Labor, to determine which

federal agencies employ scientists, and how

many scientists are employed by the U.S.

government. The list of federal agencies

employing scientists is in Box 1. This may

not be totally inclusive, but it does give an

overview of the scope of research by federal

scientists.

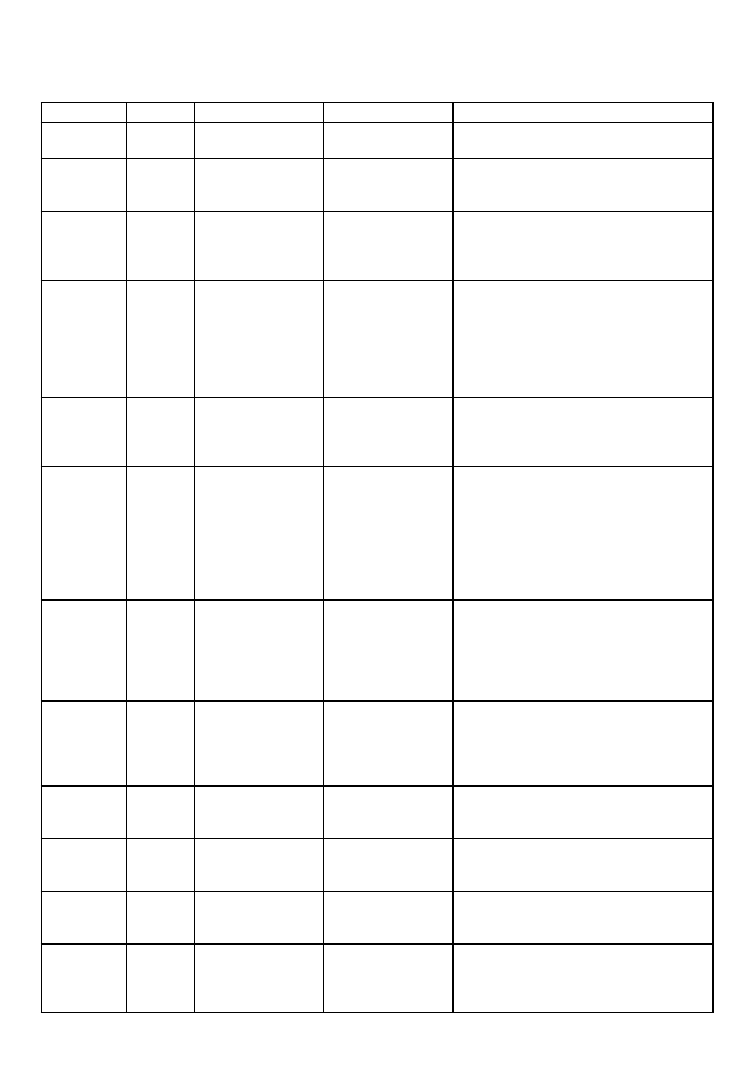

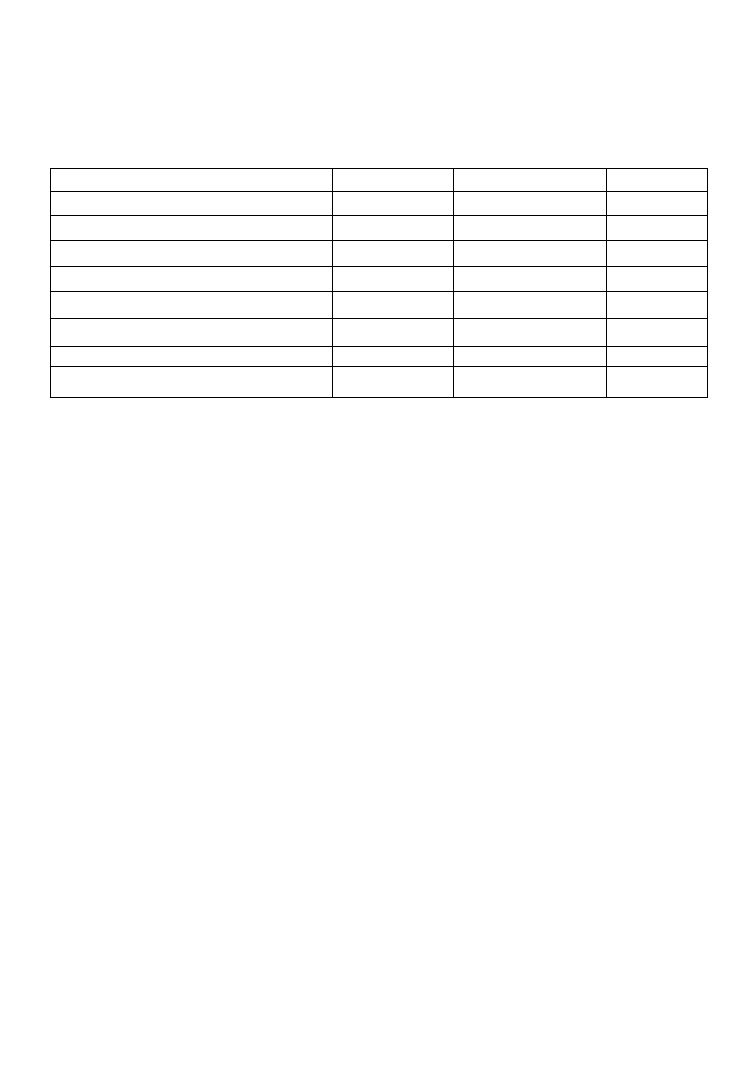

A comparison of the number of biological and

related scientists employed in government,

private industry, and academia is shown in

Table 2.

There are significantly more scientists

employed in government than in academia.

There are also more scientists in private

industry than in academia. According to a

recent Congressional Research Service report

(Sargent Jr., 2017), 6.9 million scientists and

engineers were employed in the United States,

of which 4.1% were life scientists. Given that

the majority of scientists are employed by

government agencies, it is surprising that

private industry outspends government

and academia by a wide margin (UNESCO,

2015). In 2012, for example, private industry

purchasing power parities (comparison of

currency rates among countries) was $249.6

billion, compared to $122.2 billion for

government and $24.9 billion for academia.

The amount of research and development

(R&D) performed as a share of state gross

domestic product (GDP) varied greatly across

the United States. California, Maryland,

Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, and

Washington, combined, contributed to 42%

of the national R&D expenditure (UNESCO,

2015). Each of these states contributed 3.88%

and above of their state GDP to R&D. States

with the lowest expenditure of GDP for R&D

(below 0.75%) included Arkansas, Louisiana,

Nevada, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and

Wyoming (UNESCO, 2015).

How political biases may

have an impact on

science literacy

Ideological biases (consistently liberal vs.

consistently conservative) were relatively

constant from 1994 to 2004, but diverged

greatly by 2014 (Nisbet and Markowitz, 2016).

Consumption of news is influenced by political

bias. For example, 47% of conservative voters

name right-leaning Fox News as their main

source for news, whereas liberals mostly use

the New York Times, NPR, MSNBC, and CNN.

This can influence a person’s acceptance of

scientific findings as true or false. Jamieson

and Hardy (2014) found that people with

polarized views will accept or reject scientific

findings based on whether they conform to

a group’s position (conservative or liberal),

or not. For example, on topics of climate

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

U.S. Department of Energy

Central Intelligence Agency

National Science Foundation

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Environmental Protection Agency

Nuclear Regulatory Commission

U.S. Department of Interior

National Air and Space Administration

Smithsonian Institution

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

National Institutes of Health

U.S. Agency for International Development

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

National Park Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

U.S. Forest Service

U.S. Geological Survey

Box 1. Government agencies employing scientists.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

145

change, Americans’ attitudes can affect their

interpretation of science findings (Jamieson

and Hardy, 2014; Nisbet and Markowitz,

2016). Although Americans rely on general

news outlets for science news (54%), these

outlets generally get facts about science

right only about 28% of the time (Nisbet and

Markowitz, 2016). This combination can only

be amplified in right- or left-leaning media and

when incorrect information is propagated via

social media (Bessi et al., 2015). Political bias

can also affect support for funding scientific

research as well as civic science literacy. One

has only to review the Congressional budget

process over the past 30 years to see this in

action.

The importance of

communicating science and

being involved in society

In this day and age of “alternative facts”

and “fake news,” we have a challenge in

communicating science. It is clear that science

can be misused for political agendas, and that

policy decisions based on misinformation or

ignorance can do lasting harm to society and

the environment (Oreskes and Conway, 2010).

Government scientists are using social media

to good effect to counter the information and

misinformation distributed by the current

administration via @alt_ Twitter accounts and

Facebook pages.

Scientists still have credibility for the

general public, and 44% of Americans say

they personally know, or are friends with, a

scientist (Nesbit and Markowitz, 2016). This

gives us an opportunity for outreach that is

very powerful. Scientists can reach a broad

audience at every level of society by sharing

their stories and research findings in informal

settings, through social media, by writing

articles for newspapers and blogs, and by

public lectures. We should also be working

towards presenting our findings on television

programs such as Nova and those found

on the Discovery Channel. A study by the

Pew Research Center (2009) found that the

percent of conservatives and liberals watching

science programming on these channels is

not statistically different. Jamieson and Hardy

(2014) also found that the way science is

Discipline

Government Private Industry Academia

Life, Physical, Social Science

302,780

169,500

128,010

Environmental and Geoscience

43,680

3,560

5,020

Biological Sciences

35,100

29,140

11,390

Conservation Science and Forestry

22,110

420

1,430

Medical Science

5,750

39,320

24,530

Soil and Plant Sciences

2,740

1,770

2,900

Zoology and Wildlife Biology

12,090

900

1,270

Total

424,250

244,610

174,550

Table 2. Comparison of the number of scientists employed in different science disciplines for gov-

ernment, private industry, and academia. The data are from the May 2017 release from the U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. The majority of scientists employed for each discipline is in bold type.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

146

presented matters when political biases exist.

If a scientist presents contentious findings

without advocacy, and helps the audience

to understand how conclusions were made

by using techniques that allow the audience

to make inferences by analogy, the effect of

political biases can be minimized.

Currently, there are few scientists in the U.S.

Senate or House of Representatives. One

major outcome of the misuse and abuse of

science in policy-making throughout the

21st century is a record number of scientists

running for government office this year—60

for federal office, and approximately 200 for

state office (Kaufman, 2018; Manchester,

2018). Many of these scientists are seeking

to replace politicians who have voiced anti-

science beliefs. For those of us without political

ambition, it is still important that we remain

engaged in the political process. We have a

civic obligation to vote, of course, but we can

also be effective communicators on proposed

legislation that affects policy about science,

technology, education, and the environment.

We have expertise. Let’s use it.

Literature Cited

Bessi, A., M. Colletto, G. A. Davidescu, A. Scala, G.

Caldarelli, and W. Quattrociocchi. 2015. Science vs

conspiracy: collective narratives in the age of misin-

formation. PLOS One 10(2): e0118093. doi:10.1371/

journal.pone.0118093.

Jamieson, K. H. and B. W. Hardy. 2014. Leverag-

ing scientific credibility about Arctic sea ice trends

in a polarized political environment. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111: 13598-

13605.

Kaufman, A. C. 2018. The largest number of scien-

tists in modern U.S. history are running for office in

2018. This comes at a time when there’s only one

Ph.D. scientist in Congress. https://www.huffington-

post.com/entry/science-candidates_us_5a74fffde-

4b06ee97af2ae60 (accessed 09/20/18).

Manchester, J. 2018. Record number of scientists

running for office in 2018. https://thehill.com/blogs/

blog-briefing-room/news/372200-record-number-

of-scientists-running-for-office-in-2018 (accessed

09/20/18).

Nisbet, M. C. and E. Markowitz. 2016. Americans’

attitudes about science and technology: the social

context for public communication. Commission Re-

view, American Association for the Advancement of

Science.

Oreskes, N. and E. M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of

Doubt, Bloomsbury, New York. 355 pp.

Pew Research Center. 2009. Public Praises Science;

Scientists Fault Public, Media. Available at http://

www.people-press.org/2009/07/09/public-prais-

es-science-scientists-fault-public-media/ (accessed

09/20/18).

Sargent Jr J. F. 2017. The U.S. science and engineer-

ing workforce: recent, current, and projected em-

ployment, wages, and unemployment. Congressional

Research Service publication.

UNESCO. 2015. UNESCO science report – Towards

2030. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and

Cultural Organization. 410 pp.

Welcome to

New BSA Staff Member,

Amelia Neely

The BSA is pleased to welcome Amelia Nelly

to the staff! Amelia joined BSA this September

in the leadership role responsible for the

development, coordination, implementation,

and oversight of all BSA membership and

communication programs. She is also

responsible the membership programs for the

Society for the Study of Evolution (SSE) and

the Society for Economic Botany (SEB).

Amelia comes to the BSA with 16 years

of non-profit development experience

specializing in member stewardship and

database management from positions at both

the Missouri Historical Society and Forest

Park Forever. She brings a variety of interests

and skills including member acquisition

and retention campaigns management,

website development, graphic design, event

coordination, and database management.

Amelia can be reached at aneely@botany.org.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

148

Many botanical collections like herbaria or

botanical gardens perfectly match the criteria

of the definition of a museum given by the

International Council of Museums (ICOM;

Eberwein 2011). They “…acquire, conserve,

research, communicate and exhibit the

tangible and intangible heritage of humanity

and its environment for the purposes of

education, study and enjoyment”. This short

sentence shows the importance of imparting

(botanical) knowledge in the broadest sense to

all people: communicate, exhibit, and educate!

And knowledge about plants is now more

necessary than ever before. It plays a key

role in all parts of human life, reaching from

climate, biosphere, living space, agriculture,

and industry to nutrition, medicine,

pharmaceutics, and well-being. All are

influenced directly and indirectly by human

activities. Raising the level of botanical

education is therefore imperative. On the

other hand, botanical institutions suffer

from severe financial cuts and cancellation

of activities, and some botanical gardens are

severely threatened by estate speculations.

The Botanical Advocacy Leadership Grant is

a great support for institutions under pressure

like the Carinthian Botanic Center. It allows

continuation of education, new projects, and

press campaigns that influence decisions of

politicians because they have to pay attention

to their voters.

The Carinthian Botanic Center, with its small

botanical garden, is an external department

of the Regional Museum of Carinthia in

Klagenfurt, Austria. The Center comprises

the regional herbarium (KL, 240,000 sheets),

a botanical garden, a library, and a very small

microscopy lab. Though the garden is more

than 150 years old and is very active and well

known, its history is accompanied by repeated

discussions of closure. During the last 15 years

we had to beat back three closures, and the

current lease of the area where the center is

located expires in 2020. These circumstances

require clever strategies and a lot of external

support. Up to now, the most fruitful strategy

was gathering as many fans (i.e., voters) as

possible by a vivid imparting program.

Communicating botanical topics is

therefore an essential part of Carinthian

Botanic Center’s work, because it is not only

disseminating botanical information, but

also building up a stable community of fans;

enabling free advertising in press, radio, and

TV; and aiding in discussions about function

and necessity of the institution. A published

imparting program covering all age groups

and levels of education reaching from pre-

school–age children to cooperation with

Botanical Advocacy

Leadership Grant:

Much More than a Grant!

By Roland Eberwein

Department of Botany

Carinthian Botanic Center

Regional Museum of

Carinthia, Austria

E-mail: roland.eberwein@

landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at

PSB 64 (3) 2018

149

external universities and publishing the

botanical journal Wulfenia (with a Journal

Impact Factor of 1.171) turned out to be a very

helpful working tool. In several cases, it led

to reduction of external pressure to close the

botanical garden, which allowed increasing

the quality of collections and infrastructure

during that time (Eberwein, 2004).

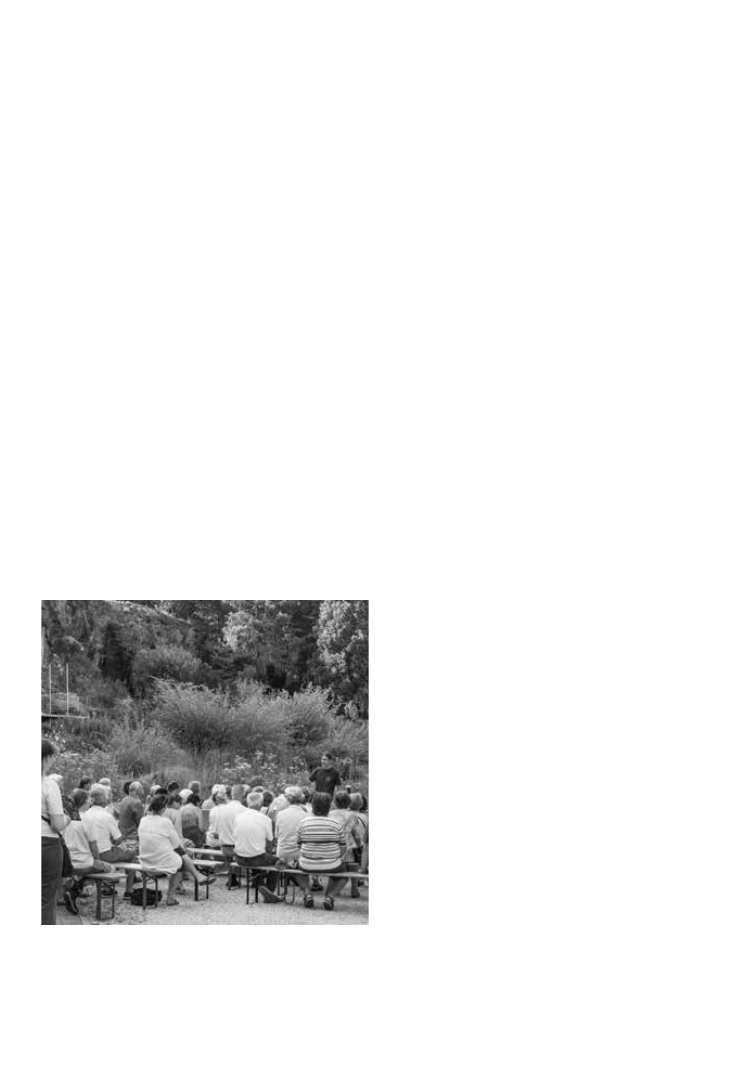

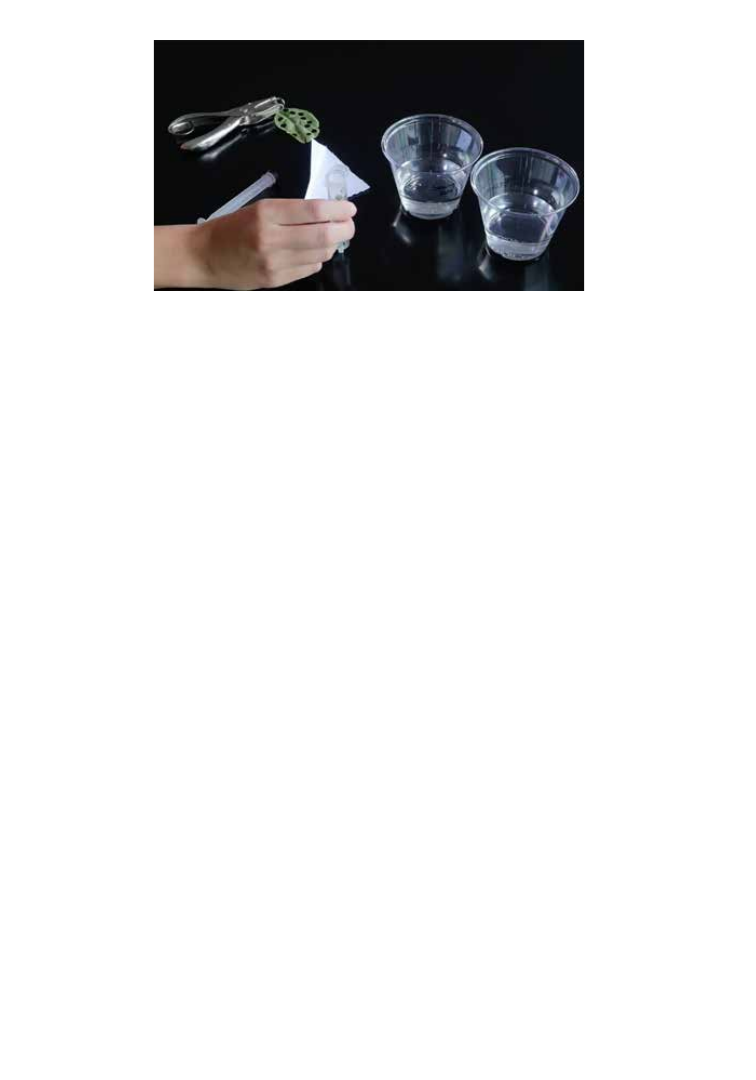

Motivated by this success, we started a

special lecture series in the botanical garden

in summer 2004. This series is a bit unusual,

because we have no lecture room, no protection

against bad weather, and no educational

infrastructure except a flip-chart and of

course many plants and ideas (Figure 1). Our

demands on this series can be summarized

as: steadily bringing botanical knowledge to

the public without fee in an attractive garden

in all weathers, imparting topics of current

interest as well as unknown and unexpected

fields of botany and ethnobotany, giving vivid

talks without computers (see Link-Pérez et al.,

2017) and never repeating a talk or topic. Up

to now, we have given more than 260 different

talks, and the number of listeners per talk

increased from 10 to 20 to sometimes more

than 80.

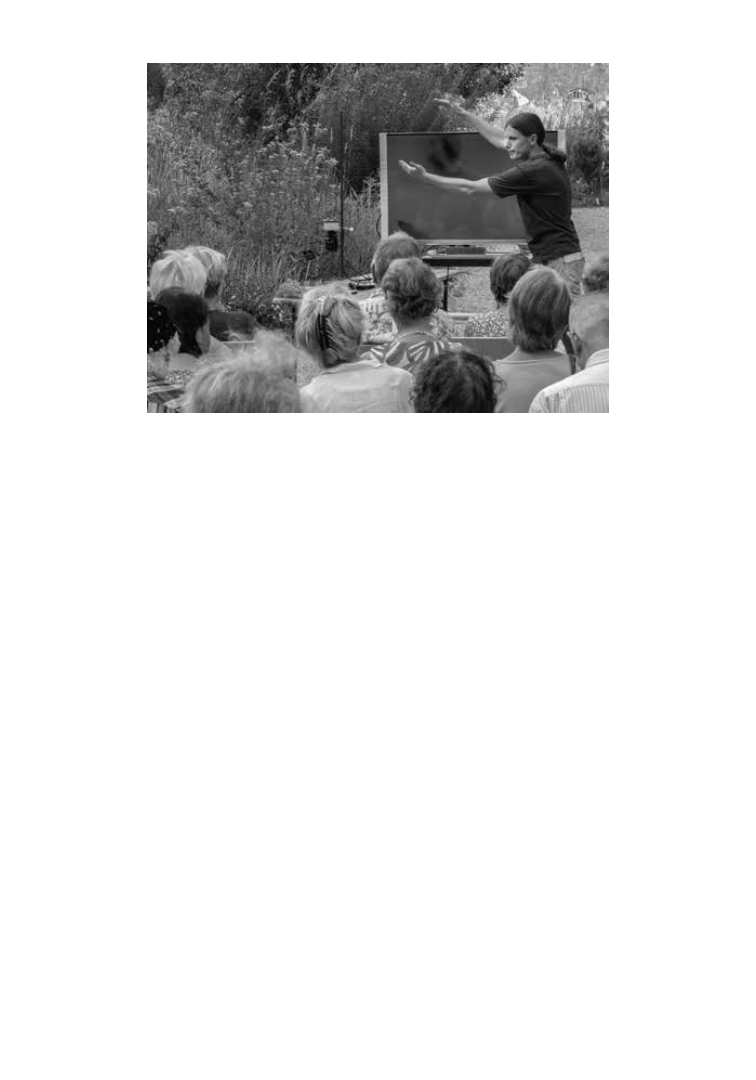

The Botanical Advocacy Leadership Grant is

a remarkable tribute to all who contributed to

the success of the talks. And it allowed us to

replace a very old and defective video camera

that was used in combination with a TV for

educational purposes until about six years

ago. We decided to buy a modern camera

that can be used without any computer. The

camera is directly connected to a screen via

HDMI, and only a second cable for power

supply is needed. Technical equipment should

not become the focus of attention, and a talk

should never be restricted by operation of

gadgets. We added an adapter to the camera

(c-mount), which allows using lenses of

SLR-cameras. Lenses with manual aperture

and a broad manual focusing ring work fine.

Aperture is preselected to f/5.6 - f/11 in order

to have a broader range of sharpness without

using additional light as well as working

distance (depending on magnification). Small

parts of plants (e.g., flowers, parts of flowers

or small seeds and fruits) can easily be placed

below the lens with minimal focusing and

without completely losing eye contact with

the listeners. Passing small objects through

the audience during a talk turned out to be

counterproductive, because objects reach

back rows much too late and listeners have

no connection between object and the topic

anymore. Showing small objects via camera

and TV during the talk with direct context

to the speech is a very fine solution. Use

of camera and TV is limited by contrast

and reflections of the screen, lighting of the

object and, in our case, by rainy weather. So, a

technical check of the equipment on location

Figure 1. Lecture about the genus Tagetes in

the Botanical Garden Klagenfurt, given by Felix

Schlatti, with 56 attendees. (Photo credit: Ro-

land K. Eberwein)

PSB 64 (3) 2018

150

prior to preparation of the lecture is strongly

recommended. Our audience enjoys the new

camera and has provided very nice feedback.

The Botanical Advocacy Leadership Grant

directed great attention of the press toward

the botanical garden, and a large report about

grant, camera, and lecture series excellently

promotes our activities and strengthens the

position of the Carinthian Botanic Center for

coming negotiations.

Literature Cited

Eberwein, R. K. 2004. Education in botanic gar-

dens? A case study of a “Potemkin’s Village” in

Carinthia (Austria). In: Novikov, V. S., D. N. Ka-

vtaradze, A. K. Timonin, V. V. Murashov, and A.

V. Sherabkov. [eds.]: Fundamental problems of

botany and botanical educations: Problems and

perspectives. Abstracts of International Scientif-

ic Conference on 200-anniversary of the Dept. of

Higher Plants of MSU (Moscow, 26-30 January

2004): 154-155. KMK Scientific Press Ltd, Mos-

cow.

Eberwein, R. K. 2011. A closed book? The botan-

ical garden in Klagenfurt is a museum. Museum

Aktuell 180: 14-17. [In German]

International Council of Museums (ICOM). https://

icom.museum/en/activities/standards-guidelines/

museum-definition/ [Accessed: 2018-08-13]

Link-Pérez, M., R. Povilus, and J. McDaniel.

2017. Cutting the cord: tips for computer-free

presentation skills. Plant Science Bulletin 63(3):

158-164.

Figure 2. Felix Schlatti uses the new video camera to demonstrate the shape of ligulate flowers.

(Photo credit: Roland K. Eberwein)

PSB 64 (3) 2018

151

This summer, the Botanical Society of

America established a new section devoted to

the professional development of faculty, and

future faculty, at higher education institutions

that fit the NSF Research at Undergrad

Institutions (RUI) criteria*. Examples of

such institutions include liberal arts colleges,

community colleges, and universities with

Master’s students and few PhD students.

Primarily Undergraduate Institutions (PUIs)

share unique opportunities and challenges.

Professors at PUIs give students invaluable

research experience in the classroom and

research labs and prepare them for further

degrees and/or professions. Some PUIs also

have extraordinarily diverse student bodies

where early exposure to hands-on research

experience can be particularly influential.

Such faculty also face distinct challenges. We

balance significant teaching responsibilities

while maintaining active research programs

predominantly with undergraduate

researchers who have diverse interests and

backgrounds. We may be the only person

within a general biology department who

studies and teaches about plants. Within our

institutions, communicating about the value

of botany, and how it fits into a broader biology

or liberal arts curriculum, may take special

effort. Networks outside of our institutions are

crucial.

We estimate that a majority of institutions

represented in the BSA are PUIs, and we have

received a feedback from many colleagues that

establishing such a network of botanists across

our institutions would benefit many.

At BOTANY 2018, the steering committee

led a well-attended and productive half-day

workshop focusing on the PUI job application

process. Our panel represented a diversity of

PUI institutions. We discussed the nature of

our jobs, our institutions, our students, and

what it is like to apply for and successfully

negotiate a faculty position. The 14 participants

included current PUI faculty, people on the

job market, postdocs, and students at PUIs.

An additional 24 people attended an informal

reception near the end of the workshop for

a discussion on broader goals and future

professional development opportunities of the

PUI Plant Network. Attendees were uniformly

enthusiastic about establishing a permanent

forum to share resources, develop further

workshops, and establish mentor relationships

between folks at similar stages of their careers

and across those stages.

We’ve created a section that will maintain and

expand a primarily online professional network

throughout the year. The PUI Plant Network

BSA section is an appropriate mechanism

to establish a sustainable PUI group, and we

expect that it will grow rapidly due to the high

number of PUI faculty members of BSA.

Primarily Undergraduate

Institution (PUI) Plant Network:

The BSA’s Newest Section

By Maggie Hanes (Eastern Michigan

University) and Rachel S. Jabaily

(Colorado College)

PSB 64 (3) 2018

152

Moving forward

We plan to host a workshop at the BOTANY

conferences annually, with rotating topics.

Future ideas include: (1) conducting research

and publishing with undergraduates, (2) a

field trip with considerations and tips for

leading class field trips from the pros, (3)

best practices for R1 PIs for preparing your

students and post-docs for careers at PUIs,

and (4) getting funded at a PUI.

We will hold an annual business meeting

at BOTANY conferences to promote

involvement, propose ideas, review issues,

and select leadership. The steering committee

currently includes: Rachel Jabaily (Colorado

College), Maggie Hanes (Eastern Michigan

University), Chris Martine (Bucknell

University), Mike Moore (Oberlin College),

and Mackenzie Taylor (Creighton University).

Membership in the section

is inclusive.

We welcome past, current, and future

faculty and students at PUIs and anyone else

interested in professional development at

PUIs. (A nominal fee of $5 has been set.)

We emphasize that we view the PUI Plant

Network Section as separate from the

Teaching Section because the PUI Plant

Network Section has a focus on professional

issues at PUIs that range far beyond teaching,

and because issues in teaching may apply to

all types of institutions. We look forward

to working with the Teaching Section and

occasionally hosting joint workshops.

For more information, please contact a

member of the steering committee. Also,

please use the hashtag #PUIPlantNetwork in

your social media.

*NSF PUI designation are accredited colleges

and universities, including two year community

colleges, that award Associate’s degrees,

Bachelor’s degrees, and/or Master’s degrees in

NSF supported fields, but have awarded 20 or

fewer PhDs in all NSF supported fields during

the combined previous two academic years.

Figure 1.

The PUI Plant Network reception from BOTANY 2018.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

153

Your social media accounts… hijacked. Your

friends… hit with a barrage of spam. Your

PC… held for ransom. Your money…. gone.

Yep, it’s 2018 and it’s well past time to take

seriously the threats out there on the internet.

It seems that over the last few years, as the

internet and other connected technologies

become more sophisticated and we depend on

them even more, there are more and greater

threats to our data safety than ever. Some of

these have hit quite close to home, impacting

the officers and sectional leaders of the

Botanical Society of America. We would like

to remind all of our members of what to look

for and basic steps to take to protect yourself

from those out there who seek to do us harm.

The basic problem is that there is a lot of

money to be made doing nefarious things

on the internet. Bad actors get big bucks to

spread spam about cheap Ray Bans, take

control of your computers and only release

them for a ransom, or to gain access to your

money through insecure or stolen login

accounts. Here are some examples of the main

approaches they take to do this.

By Rob Brandt

Information and

Technology Director-

Botanical Society of

America

rbrandt@botany.org

Protecting Your Online Presence

Helpful Hints from the BSA’s

Information & Technology Director

Account Hacking

The goal is to find out what your passwords are

to your website accounts. Once they have even

one of your accounts, they will attempt to find

other places where that account information

is used, such as banks, investment companies,

PayPal, Facebook, etc., because many people

use the same login information on many

different websites. They can use a variety of

methods to do this: “dictionary” attacks, where

they try and login at a site they know you use,

using all words in a dictionary or other source

until they find one that works. Or they’ll look

you up on Facebook to learn about you, and

use your pet’s name, your hometown, your

spouse’s name or other information to guess

your password or the security questions

that will allow them to reset your password

themselves.

Phishing

Phishing is when the bad actors try to get

someone—anyone—to respond to a message

that will allow them to get your login

information, credit card numbers, social

security number, etc. They aren’t targeting

you personally, but once they have your

personal information they will do bad things

with it. An example would be a “tech support”

message from Microsoft, Apple, Bank of

America, the IRS, etc. that prompts recipients

to click on a link. The page it takes them to

looks exactly like the real site it pretends to

be, and they are prompted to log in or make

PSB 64 (3) 2018

154

President, and Lucinda the Treasurer. All

this information is publicly available on the

BSA “current officers” website. The phisher

used the e-mail addresses listed on that page.

What’s even more impressive is that this

e-mail is signed by “Andi”, and it’s not evident

on our page that Andrea uses that nickname.

They apparently did other research elsewhere

to find that—perhaps her social media

accounts. It’s important to recognize that no

data breach enabled this attack; it’s all public,

benign information. But it’s put together in a

way that would be totally believable if it were

a normal thing for Andrea to ask Lucinda for

a transfer of funds. (It’s not.) This was a very

clever attack. “Spear phishing” is called that

because it’s very similar to actual spear fishing,

in which the fisher dives, spots a particular

fish, and targets it.

Protecting Ourselves from

Attacks

So how do we protect ourselves from these

attempts to do us harm? Short of unplugging

from the internet, there are a few basic things

we can do to make it difficult for bad actors to

succeed.

Passwords

Use safe passwords, change them fairly often,

and don’t use anything that can be found in

a dictionary or other information about you

online. Obviously don’t use “password” or

“123456” or other silly things. If you do, know

that you are already hacked. Many websites

require you to have a secure password using

certain rules, but by far the most important

thing you can do is to use a pass phrase, not

a pass word. String together a short sentence

that will be easy to remember, and yes, include

a payment. Once you do that, the bad guys

have your information and/or your money. It’s

called “phishing” because it is very much like

real fishing; you put some bait on a hook and

cast it into the water, hoping a fish will bite.

When they bite, you’ve caught your fish.

Spear Phishing

Spear phishing is very much like regular

phishing, except the phisher has his/her eye

on you specifically and are setting bait that

will appeal to you specifically. It takes a great

deal more effort for them to do this, but the

payoff is far higher if it works. I will use an

incident we recently encountered at the BSA

as an example:

From: Patsy Yates <winstonrose00@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Sep 19, 2018 at 4:00 AM

Subject: Urgent Transaction

To: lmcdade@rsabg.org

Hello Lucinda

Can we make an urgent Transfer of $5,600

today ? So I will forward you the vendor

details for payment. Thanks

Best Regards

Andi Wolfe

This message sent to Lucinda McDade (BSA

Treasurer) purported to be from Andrea Wolfe

(BSA President) asks to transfer $5,600 “today”.

(Lucinda recognized that it was suspicious

immediately and alerted us.) There are a

few items in this e-mail that are impressive,

showing the research the phisher did to make

it appear to be an authentic request. There’s

a genuine relationship between Lucinda and

Andrea, in that they are both on the Board of

the Botanical Society of America. It seems

reasonable that Andrea would request funds

from Lucinda because Andrea is the current

PSB 64 (3) 2018

155

a few odd characters just to make it extra

difficult to guess. You should also update

your passwords from time to time, because

you may not know your password has been

compromised until much later.

Password Managers

Use an encrypted password manager to keep

track of your passwords. Don’t just save

them to a simple file on your computer or

smartphone, because if hackers gain access

to your device, they will then have all your

passwords. One of the first things a hacker

will do on a newly hacked device is search

it for “password” to find everything stored

there. Password Managers are designed to

keep them safe. The data are stored in an

encrypted database, and can only be accessed

if you have a password. Use a different

password on the password manager than the

one you use for the device, so that the hacker

will need to know TWO passwords to get at

your other passwords. There are numerous

password managers available, but one good

one available for many devices, and is free,

is KeePass (https://keepass.info/download.

html). The database format is universal, so

you can keep your password database on all

your devices.

Single Sign-on

Many websites allow you to sign on with an

account from another service. For example

you can sign on with your Facebook, Twitter,

Gmail or Amazon account. There are some

downsides to doing this, but the one huge

advantage is that the site you are using

your Facebook account on does not get your

password. The least trustworthy sites are

the ones from small operators who cannot

afford full-time security specialists. Those

are the sites that get breached the most. It’s

a really good thing if they never even see

your password. The downside of this is that

Facebook and others can then share other less

critical information with the site, such as your

e-mail address, list of friends, etc. When you

first create a new account using your existing

Facebook or other account, you should be

notified of what is being shared; note it and

consider whether it’s an acceptable tradeoff

for you.

Use Plain Text E-mail

We all like nicely formatted e-mail. Hackers

like it even more, because it allows them to

obscure what they are doing, making it more

likely that you will click on some variety of

phishing attack. The previous example of the

spear phishing attack is a perfect example.

Everything looks legitimate except for the

“from” line at the top. The message purported

to be from Andrea Wolfe, but the “from” said:

“From: Patsy Yates <winstonrose00@gmail.

com>.“ In this article, that’s plainly obvious.

But most people pay more attention to the

content of a message than who it’s “from.”

The phisher could have taken an extra step of

changing the “from” to:“From: Andrea Wolfe

<winstonrose00@gmail.com>“ and it would

have been harder for Lucinda to see who it

really was from.

Links in the text are similar. A plain text

e-mail to a phishing site might display a link

such as https://wellsfargo.asldkjalfjhlaksdjf.ru,

whereas a nicely formatted e-mail will simply

show “Wells Fargo”, and you can only see the

URL it points to by hovering your mouse over

it, or (yikes) clicking on it. And once you click

on it, and it looks like a Wells Fargo page, are

you going to look at the URL to make sure

PSB 64 (3) 2018

156

that’s really where you are? Probably not.

As a bonus, recent studies have shown

that plain text e-mails get read more often

than formatted ones. I believe the reason is

that formatted e-mails look too much like

newsletters, and no one reads newsletters

(right?). So there’s additional reason to just

keep it plain. Just say “no” to html e-mail.

Just pay attention!

Be aware that the internet is not a safe place,

and keep your mind engaged when you are

browsing the web or reading your e-mail. The

e-mail to Lucinda failed because it was an odd

request, and she knew it. Think about whether

you were expecting to receive requests for

information, or tasks to perform. Don’t

download files just because someone asks you

to. There’s no shame in verifying that it really

came from whom it claims to be from. Look

at URLs that links send you to, and look at the

“from” on e-mails to be sure they make sense.

The internet can be a dangerous place, just like

anywhere else in the world. But you don’t have

to get hurt if you do the basics to keep yourself

safe. Understand where the dangers are and

what they want to do, keep your sensitive

information safe, use good security measures,

and above all pay attention.

PSB 64 (3) 2018

157

Science and Civic

Participation

Before becoming scientists, we were citizens

of somewhere. As such, we have a basic

civic responsibility to make an informed

vote in our registered locale. What we

may forget in our busy professional lives

is that this is our basic responsibility to ensure

our democratic institutions continue to

operate. As scientists, we can easily overlook

additional civic duties we have earned by

developing our expertise: educating and

engaging with those trying to understand

science-related policy issues, evaluating

policy positions on their empirical merits,

and holding our elected leaders accountable.

The challenges of the 21st century require scientific

solutions, evidence-based decision-making, and

greater civic engagement by scientists. Many of

us are now more inspired than ever to become

involved in our democracy. However, the

multitude of options can be overwhelming,

resulting in inaction. Here, we provide a

framework for participating in civic life as a

scientist in ways that can effect real change.

By Ingrid Jordon-Thaden (University of California Berkeley),

ASPT EPPC Chair, Krissa Skogen (Chicago Botanic Garden),

and Kal Tuominen (Metropolitan State University), BSA PPC

Co-Chairs

Commit to a Satisfying

Connection

Determine the amount of time you can commit

and the type of engagement that is compelling

to you. Then push yourself outside of your

comfort zone, just as you do in other areas of

your life. You will be more effective if you are

realistic about your strengths, interests, and

what you can commit. Few of us will spend

a career in science policy, but most of us can

create time to speak or volunteer at a one-day

event. All efforts are important, no matter

how small!

Evaluate and Hold

Accountable

Scientists with policy experience seem to

share a common refrain: most policymakers

value scientific input, but they don’t always

remember to create a seat at the table for

those who can provide it. Evaluating elected

officials and candidates for office on their

willingness to reserve a seat for us is a deeper

way scientists can support civil society.

Do you know where

candidates in your district

stand on science issues? How

have incumbents voted in

the past? For the midterm

elections, American Institute

of Biological Sciences (AIBS)

has teamed up with 11 other

science-related organizations

to create the Science Debate

2018 questionnaire. Whether

and how candidates respond

Public Policy News

PSB 64 (3) 2018

158

can help us evaluate candidates’ ability to

lead. View candidates’ responses at https://

sciencedebate.org/sciencedebate-index.html.

Don’t see your candidate’s answers? Send an

e-mail encouraging him or her to respond!

Another way to hold candidates accountable

is to attend a town hall or debate and ask

questions about their views on science-related

issues. Questions might relate to government

funding for science, climate change, public

lands, food security, natural disaster

preparedness, or other issues. The goal is to

get candidates to state their positions on the

record.

Educate and Engage

Politics can muddy the waters on scientific

issues for the general public, even when the

weight of evidence is clear to us. Election season

is a great time to educate voters about scientific

consensus and its connection to policy. We can

also educate each other: share what you learn

about candidate positions and voting records with

your peers to help them make an informed vote!

Finally, consider helping a science-savvy candidate

get out the vote. Campaigns need the most

volunteers in the week before the election. Voter

engagement involves calling and knocking on the

doors of likely supporters. Speaking with undecided

voters in a close election can help determine the

outcome! You can practice your pitch during a

brief volunteer training: “As a scientist, I value using

evidence to make policy decisions that impact the

lives of all Americans. [Candidate X] has a track

record of supporting science and using knowledge

and sound reasoning in policy decisions. For

these reasons, I feel they are a strong candidate

for office and encourage you to vote for them

on November 6.”

If all of that seems too easy, we have one last

question: have you considered running for

office in 2020?

PSB 64 (3) 2018

159

Just about 2 1/2 weeks before the start of

our annual conference this year, staff at

the Botanical Society of America received

word—via Twitter—that at least two of our

members were denied U.S. visas and were

unable to attend our BOTANY 2018 meeting

in Rochester, MN. The conference is a unique

and welcoming venue where botanists share

current research, develop collaborations,

establish and strengthen networks, and

generally enjoy the camaraderie of the plant

science community. We knew the travel ban

would affect the scientific community, but

until we saw their tweets, we did not know how

many plant scientists would miss our meeting.

As soon as we learned of their plights, we leapt

into action to figure out how we could help

them to participate.

As with many professional conferences at

two weeks out, the sessions’ agendas had

already been carefully arranged, which made

the creation of a separate “remote presenter”

session unlikely. However, we knew we could

and should allow our missing attendees to

present their work remotely; we just needed

to work out the details. The BSA does have

How the BSA Helped Members

Affected by the the U.S. Travel

Ban at BOTANY 2018

a Zoom Video Communications account,

which has been consistently reliable and

effective for remote meetings and training

webinars for our organization. Therefore

we were confident we could pull in our two

international participants—one in Canada,

whose Ph.D. was completed on the west coast

of the United States, and one in Denmark,

who was slated to present work completed at

the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.—via

Zoom.

Preparation

To get started, we needed to make sure that

our remote presenters felt comfortable with

Zoom. We knew that the transition from local

to remote presenter and back again could be

tricky, especially with the tight timetable for

each session. In light of this, one week prior

to their sessions and three days before the

start of the conference, we held a practice ses-

sion with both scientists to allow them time

to practice using the Zoom platform - finding

and adjusting the video and audio controls,

sharing their screens, etc. Each presentation

looked good and worked smoothly during the

practice sessions, and each presenter noted

and set the proper microphone and camera

settings for the real deal.

Once the BSA staff were at the Mayo Clinic

Civic Center, in Rochester, MN, we set up

practice Zoom meetings to establish the

appropriate settings on the computers to be

used in each room. The one caveat, we knew,

would be the internet connection, because

By Jodi Creasap Gee, PhD

BSA Education Technology

Coordinator

E-mail:

JCreasapGee@botany.org

PSB 64 (3) 2018

160

we were using Wifi and not the hardwired

connection. There was a very real chance that

the remote presentations would hit a snag

with an internet connection that could be

laggy due to excessive use. After our on-site

practice run looked good, we felt ready to roll

with the presentations.

Delivery

The reality of the situation was that we needed

to use the hard-wired internet connection

in the session rooms to guarantee that there

would be no interruptions to the remote

presentations, which is what happened with

the first presenter. Her audio became garbled,

and the slides were pixelated. We quickly

overcame the issue by tethering the room

computer to a phone’s hotspot for the duration

of the 15-minute presentation. The second

presentation went a little more smoothly, and

we immediately starting making notes on

what to do in 2019, in case we need to address

this issue in the future.

Outlook

Several of us have brainstormed about options

and possibilities for subsequent meetings,

and we are determined to be prepared for the

possibility of remote presentations. While

our ultimate goal is to develop a protocol for

remote presenters denied U.S. visas, we do

have a few ideas of what we can do better next

year.

First and foremost, remote presenters need

more practice ahead of time. This means they

should run through their presentations at least