IN THIS ISSUE...

SPRING 2017 VOLUME 63 NUMBER 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Pam Diggle on Careers

Beyond the Academy...p. 17

Round-Up of Student

Opportunities........p. 23

Star Project Award Winners

in PlantingScience...p. 22

#actuallivingscientist

Spring 2017 Volume 63 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 63

From the Editor

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Environmental Sciences

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22904

kal8d@virginia.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Biology &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.ed

u

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

l

inkperm@oregonstate.edu

Shannon Fehlberg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

Greetings!

This is the first issue of Plant Science Bulletin of

2017. This new year is already proving to be a

challenging one for many, including those of us

who work in science and education in the Unit-

ed States. Nearly every day, scientific knowl-

edge is being disputed, groundbreaking envi-

ronmental legislation is being attacked, and the

global network of scientists is being threatened.

As botanists, we have the responsibility to act

in whatever ways we can, individually and as a

group, to mitigate the actions of an administra-

tion that is blatantly anti-science.

Some action is underway. In January, the BSA

co-signed a letter with 151 other scientific en-

tities protesting the Executive Order on Immi-

gration banning travel from seven Muslim-ma-

jority countries. This letter pointed out that

scientific progress requires the flow of ideas and

people across borders. The BSA is once again

supporting the travel of two members to the

2017 Biology and Ecological Sciences Coalition

Congressional Visits Day and, in conjunction

with ASPT, supporting local efforts with the Bo-

tanical Advocacy Leadership Award. Individual

BSA members are planning to participate in the

March for Science in Washington, DC in April.

It is my hope that we, the Botanical Society of

America, will be at the forefront of this fight as

it continues, providing avenues for action and

support for other members and representing

plant science within the broader scientific com-

munity. After all, as the BSA twitter feed is fond

of reminding us, we are #notaquietscience.

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Are you ready for Botany 2017 ................................................................................................................2

Public Policy Awards, 2017 .........................................................................................................................3

ASPT and BSA at Plant Science Research Network ..................................................................3

Public Policy Opportunities at Botany 2017 .....................................................................................4

First Annual Botany Advocacy Leadership Grant Supports Outreach in Oklahoma .4

Convergent Evolution of National Science Education Projects:

How BSA Can Influence Reform (Part 2) ............................................................................................6

The

American Journal of Botany welcomes your collaboration in 2017 .....................14

Why publish your next methods paper in

Applications in Plant Sciences? .................15

SPECIAL FEATURE

Careers Beyond the Academy ...............................................................................................................17

SCIENCE EDUCATION

Over 2000 Students Conduct Plant Science Investigations This Fall Through

PlantingScience.org ......................................................................................................................................21

Visit BRIT during Botany 2017 for a Tour or Workshop ..................................................................................................21

Life Discovery Conference—Data: Discover, Investigate, Inform ..........................................22

STUDENT SECTION

Round-up of Student Opportunities ....................................................................................................23

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Eagle Hill Institute Natural History Science 2017 Field Seminars ....................................31

Pam and Doug Soltis Awarded the 2016 Darwin-Wallace Medal .....................................31

In Memoriam

Thomas Norwood Taylor (1938—2016) ..................................................................................33

Hugh Iltis (1925–2016) .....................................................................................................................36

BOOK REVIEWS

Conservation ....................................................................................................................................................39

Ecology ................................................................................................................................................................41

Economic Botany ...........................................................................................................................................43

Education ............................................................................................................................................................48

History .................................................................................................................................................................49

Systematics ......................................................................................................................................................51

PSB 63 (1) 2017

2

Dr. Ranessa Cooper started coming to BOTANY conferences

as an undergrad 20 years ago. "This is my meeting,” she

stresses. "There is no better meeting to adopt. I love to come

because of the great people and the breadth of science."

Are you ready for Botany 2017?

Fort Worth, Texas

June 24 -28

Plenary Lecturer - Robin Kimmerer

Emerging Leader Special Lecture - Michael Barker

Annals of Botany Special Lecture - Anna Traveset

Regional Botany Special Lecture - Barney Lipscomb

and Jason Singhurst

What can you expect from BOTANY 2017?

It is one of the friendliest places to present your research, make

connections, and find collaborators.

“The size of the Botany Conferences is perfect, not too big or

too small,” says Dr. David Gorchov. “And, I am exposed to the

cutting edge research outside my discipline of ecology.”

Register now

www.botanyconference.org

You are going to love our location!

Sundance Square and Downtown Fort Worth

have so much to offer!

Other than great places to eat and drink, from cheap to fancy,

be sure to devote a few hours to walking around and visiting

the shops, the Sid Richardson Art Museum, Bass Hall,

the Water Gardens, and more.

Molly the Trolley runs through downtown Fort Worth 7 days a

week from 10am -10pm. Best of all—it’s free!

3

SOCIETY NEWS

By Marian Chau (Lyon Arboretum University of Hawai‘i at Mā-

noa) and Morgan Gostel (Smithsonian Institution), Public Policy

Committee Co-Chairs, along with Ingrid Jordon-Thaden (Uni-

versity of California Berkeley), ASPT EPPC Chair

Public Policy Awards, 2017

Congratulations to Andre Naranjo and Mari-

beth Latvis, Ph.D., recipients of the 2017 BSA

Public Policy Award, and Christopher Tyrell,

recipient of the ASPT Congressional Visits

Day Award! Andre, Maribeth, and Christo-

pher will be traveling to Washington, DC to

participate in the 2017 Biological and Ecolog-

ical Sciences Coalition Congressional Visits

Day (25–26 April 2017). Look for a write-up

of their experiences in the next issue of the

Plant Science Bulletin!

ASPT and BSA at Plant

Science Research Network

The Steering Committee of the Plant Science

Research Network (PSRN) met February

9-10, 2017, in Tucson, AZ to discuss the cur-

rent draft of the National Plant Systems Initia-

tive (NPSI) and review progress on strategic

planning for Plant Science, particularly in the

areas of Training, Cyber-infrastructure, and

Broadening Participation. The NPSI docu-

ment was created by the PSRN, which is an

NSF-supported Research Coordination Net-

work ultimately consisting of 15 professional

societies given the task to collectively imag-

ine the future of plant sciences and its role in

agriculture, biodiversity, and ecosystem and

food security into the future. This effort has

been in progress since 2011 with the publi-

cation of the Decadal Vision (http://bti.cor-

nell.edu/our-research/enabling-technologies/

decadal-vision/) and the establishment of

the Plantae community (http://www.plantae.

org/), and now is culminating in the develop-

ment of the NPSI to help direct policy, edu-

cation, and training decisions for establishing

funding and developing research planning

and collaboration across the plant sciences.

Our representatives who attended this Feb-

ruary meeting from BSA and ASPT—Alli-

son Miller and Chelsea Specht, respective-

ly—along with BSA’s official representative,

Michael Donoghue, will help our societies’

interests be represented in the planning and

keep us informed on upcoming federal ini-

tiatives or opportunities for research, train-

ing, and broadening partici-

pation. Ecological Society of

America (ESA) representative

Evan DeLucia was also in at-

tendance, representing addi-

tional support for the fields

of plant research supported

by BSA and ASPT. Be on the

lookout for more informa-

tion!

PSB 63 (1) 2017

4

Public Policy Opportunities at Botany 2017

Want to know how to be more involved in public policy communication for science? Sign up

for the AIBS Communicating Science to Decision-makers workshop at Botany 2017, held on

June 25 from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM. This three-hour workshop will be presented by Dr. Robert

Gropp, AIBS Interim Co-Executive Director. Space is limited to 30 participants and will fill up

soon!

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact the ASPT Environmental and Public

Policy Committee or the BSA Public Policy Committee. More details are in the call for appli-

cations.

Michael Dunn sent the following thank-you

note to the ASPT Environment and Public Pol-

icy Committee and BSA Public Policy Com-

mittee regarding the Annual Botany Advocacy

Leadership Grant that Dunn and the Oklaho-

ma Native Plant Society received.

Thank you for your support of botanical

public outreach by your generous award of

$1000 as an Annual Botany Advocacy Leader-

ship Grant, through me, to the Southwestern

Chapter of the Oklahoma Native Plant Society.

The goal of this grant is to bring together as

many of the institutions and organizations in

southwestern Oklahoma who are at least in

part like-minded in that they attempt to use

plants to enhance the quality of life of the re-

gion. And to use plants as they relate to nat-

ural history, anthropology and archeology,

horticulture and agriculture, as well as plants

as an excuse to simply get outside.

We are well on our way to achieving many

of our goals with our partners including

The Oklahoma Native Plant Society, Wich-

ita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, Friends of

the Wichita’s, Fit Kids of SW Oklahoma, The

Medicine Park Aquarium and Science Center,

Cameron University, Oklahoma State Univer-

sity Extension Service, The Museum of the

Great Plains, and the Greater Southwest Okla-

homa Anthropological Society.

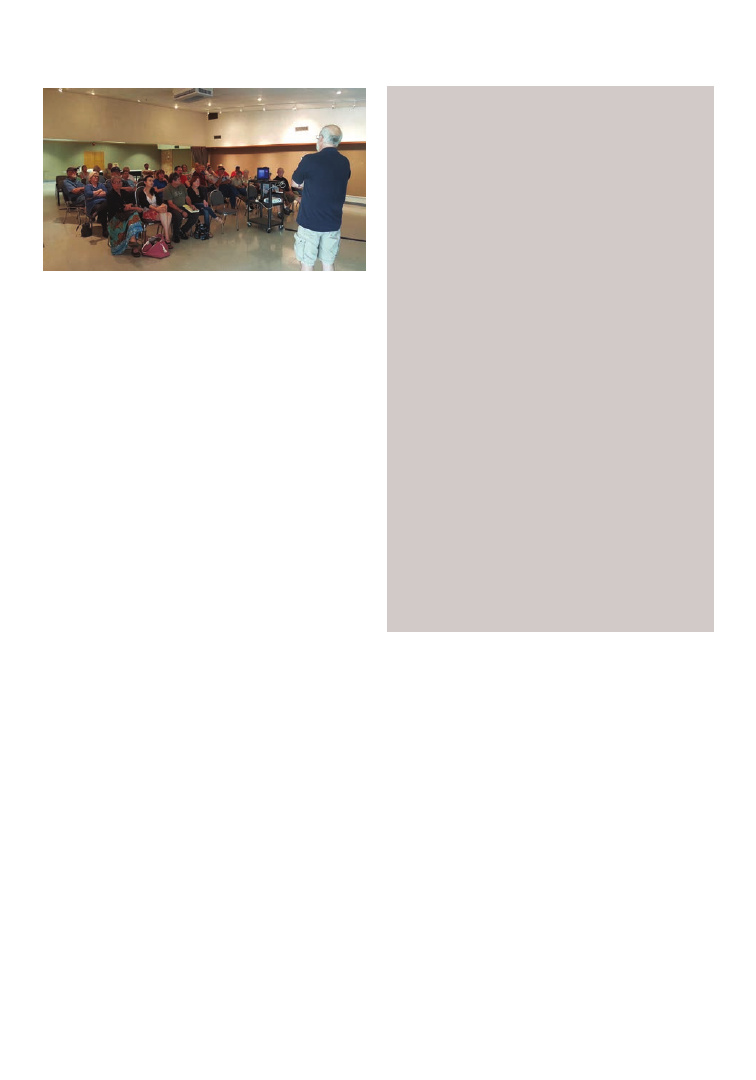

Our first sponsored event was 27 August 2016

at The Museum of the Great Plains, and was

co-sponsored by the Greater Southwest Okla-

homa Anthropological Society. Bob Blasing, a

retired anthropologist with the Bureau of Rec-

lamation spoke on “How Early Great Plains

Tribes used Seasonal Travel to Obtain Re-

sources”. More than 30 people attended (Fig-

ure 1), including some unexpected, but most

welcome guests. The Secretary of Agriculture

for the Comanche Nation attended, and he

and I were able to discuss historical plant use

by the Comanche Tribe. This is particularly

exciting as the tribes here in “The Nations”

(a.k.a. Oklahoma) have been very protective

of their ethnobotanical heritage, and this was

an incredible breakthrough. Our collabora-

tion continues.

On 8 October 2016, we sponsored the Annual

Meeting of The Oklahoma Native Plant Soci-

ety. We met that morning at The Environmen-

tal Education Center of the Wichita Moun-

tains Wildlife Refuge (WMWR) and several

field trips were available including Aquatiic

Plants of the WMWR, and a discussion/walk

First Annual Botany Advocacy Leadership Grant Supports

Outreach in Oklahoma

PSB 63 (1) 2017

5

To future recipients of

this [Botany Advocacy

Leadership Grant], I

cannot express how

rewarding it is to work

with these grassroots

organizations. But

they are grassroots

volunteer organizations

that require patience

and understanding, but

believe me, that patience

will be rewarded as you

will be working with

some truly dedicated

and enthusiastic amateur

botanists and other types

of plant people.

Figure 1. Bob Blasing speaking to a mixed

crowd at the Museum of the Great Plains. The

Secretary of Agriculture for the Comanche Na-

tion is in the fourth row, far right in a red shirt,

hidden except for his cowboy hat.

about designing and constructing self-guided

plant tours. Lunch was provided by the Friends

of the Wichitas, and Susan Howell, the Visitor

Services Coordinator for WMWR, spoke af-

ter lunch on “Maintaining the Health of the

Mixed Grass Prairie.” The Keynote Speaker

that evening was David Redhage from the

Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture, who

spoke on “Pollinators and Native Plants.”

In April or May of 2017, we will join with The

Medicine Park Aquarium and Science Center,

Fit Kids of SW Oklahoma, and Lawton Public

Schools to bring eighth graders to The Medi-

cine Park Aquarium and Science Center for a

native plant and pollinators workshop. These

details are still being worked out.

To date most of the funds provided by the

grant have been used to pay travel expenses

for our speakers, but we hope to have enough

money left to pay for the busses to bring the

eighth graders to our workshop.

Thank you to the American Society of Plant

Taxonomists and The Botanical Society of

America for this Botany Advocacy Leader-

ship Grant. I hope we have used, and are us-

ing your funds as you had hoped. To future r

ecipients of this grant, I cannot express how

rewarding it is to work with these grassroots

organizations. But they are grassroots volun-

teer organizations that require patience and

understanding, but believe me, that patience

will be rewarded as you will be working with

some truly dedicated and enthusiastic ama-

teur botanists and other types of plant people.

-By Michael T. Dunn, PhD, Professor, Depart-

ment of Agriculture and Biological Sciences, Cam-

eron University, Lawton, Oklahoma 73505

USA

PSB 63 (1) 2017

6

The first part of Dr. Uno’s speech, taken from his

address at the Botany 2016 conference, can be

found at http://botany.org/file.php?file=Si-

teAssets/publications/psb/issues/PSB-2016-62-

3.pdf.

Convergence of National

Science Education Projects

There are multiple signs that the scientific

community in academia has accepted science

education as a legitimate activity in which

colleagues can engage. In Part 1 of my talk, I

identified seven signs that indicate to me that

we have reached the tipping point in science

education. The eighth, and last, indicator is

the fact that several national science educa-

tion reform projects have converged on sim-

Convergent Evolution of National

Science Education Projects: How

BSA Can Influence Reform (Part 2)

Remarks from Botany 2016 by President-Elect

Gordon E. Uno

By Gordon E. Uno,

BSA President-Elect

University of Oklahoma

ilar messages to the biology community. The

Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

from the NRC (2013), Vision and Change

from AAAS (2011), the AAC&U’s LEAP Ini-

tiative and High Impact Practices (2011), and

the College Board’s revision of the Advanced

Placement (AP) Biology course in 2012 are

just four of these large-scale projects that have

and will continue to have great impact on sci-

ence education in the United States.

How are these projects converging? I think

there are five major ways these major projects

are similar in their explicit and implicit rec-

ommendations to the science community:

1. Student outcomes or competencies should

be used to organize a course or program—

competencies are those characteristics that

we desire students to possess at the end of in-

struction and are measures of student learn-

ing about subject knowledge and ability to

use important skills. What is different from

previous reports is that competencies help us

determine how students should learn science

practice skills while they are learning con-

tent; neither content nor skills are taught in

isolation. For instance, there should not be a

50-minute lecture on photosynthesis without

students working with data or graphs or de-

signing experiments related to the subject. In

PSB 63 (1) 2017

7

addition, we need to help students think about

their own learning—what do they understand

and what are they still confused about?

2. These national science education projects

emphasize that the investigative process

of science, including critical thinking and

inquiry skills and student investigations,

should be the cornerstone of all science

courses. Critical thinking and inquiry skills

(Box 1) have often been limited to laborato-

ry settings, but we know that they should be

practiced throughout a course. In terms of

research, students should be able to conduct

authentic research to the extent possible and

be exposed to science as a process as soon and

often as possible. Thus, faculty need to find

ways to allow students to practice the skills

shown in Box 1 every day—while not all of

them can be used on the same day, students

should be engaged in at least one of them ev-

ery day.

3. Faculty should focus on student learn-

ing and understanding instead of worrying

about what to teach, i.e., become more “stu-

dent-centered.” This happens when a facul-

ty member is more concerned about helping

students understand whatever information is

taught instead of just being worried about what

to teach.

4. To do all of the above, faculty are urged

to use “evidence-based” activities (Box 2),

those teaching methods that science edu-

cation literature indicates are effective in

helping students learn science. As one might

expect, these activities are infused with inqui-

ry and critical thinking skills, and faculty are

encouraged to use these activities every day in

both lecture and lab. The important issue here

is that, although we have a good idea of what

works in the classroom and although most

faculty have heard about some evidence-based

activities, few faculty have the knowledge or

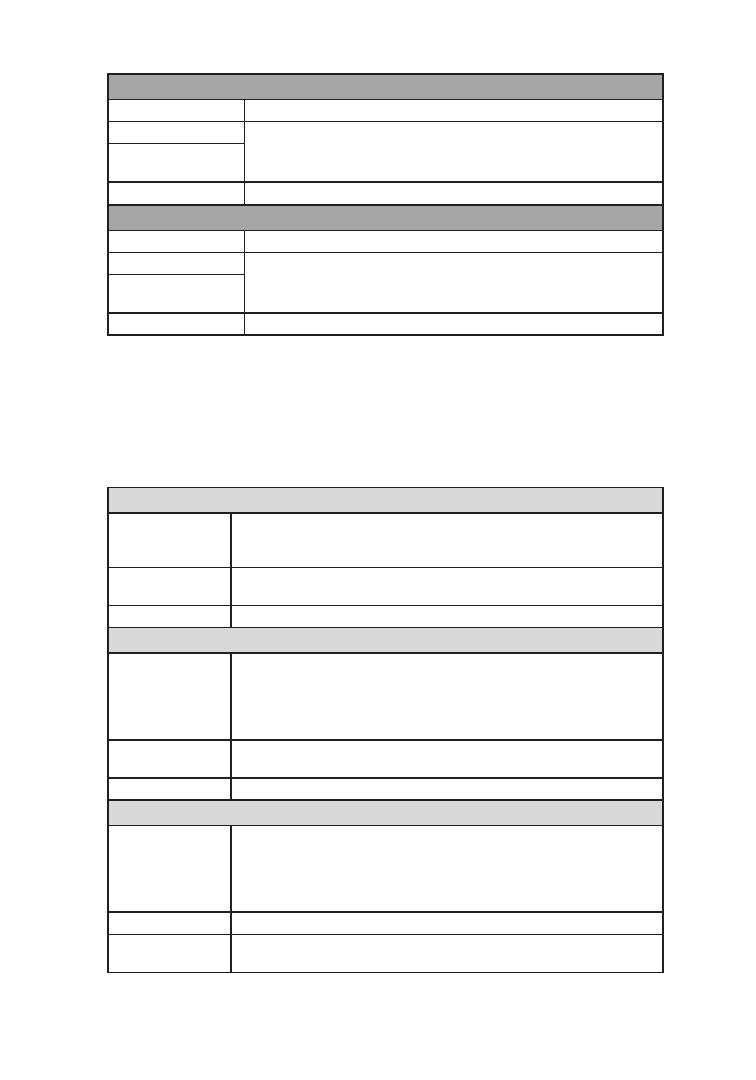

Box 1. A List of Critical-Thinking

and Inquiry Skills

1. Make careful observations and ask

good questions.

2. Develop appropriate hypotheses and

explain predictions.

3. Design a controlled experiment.

4. Collect, process, and interpret data

(quantitative skills).

5. Discuss ideas and draw conclusions.

6. Infer and generalize.

7. Distinguish between cause and effect

vs. correlation.

8. Recognize assumptions and biases.

9. State, evaluate, and justify claims us-

ing evidence.

10. Communicate science effectively

(explain concepts in your own words).

11. Apply knowledge to new situations;

make connections between concepts.

experience to implement these activities ef-

fectively. This raises the importance of faculty

professional development to inform facul-

ty of these methods and to let them practice

and think about how these practices would be

used intentionally in their classrooms.

5. National science education projects have

also converged on their position regarding

the teaching of science content; while con-

tent is essential, less is definitely more, and it

is equally important for students to be able to

apply the content they have learned to new

situations and to connect ideas, facts, and

concepts to each other. Additionally, there

PSB 63 (1) 2017

8

Box 2. What Works: A List of Teach-

ing/Learning Methods Demonstrated to

Be Effective in Helping

Students Learn Science

1. Authentic Student Research

2. Experience Science as a Process Through-

out Course

3. Metacognitive Activities

4. Drawing to Explain

5. Writing for Understanding

6. Explaining Concepts in Their Own

Words

7. Creating Summaries of Content and Re-

search

8. Peer Instruction

9. Communicate Science and Discuss Con-

cepts/Problems

10. Problem Solving (problem-based learning)

11. Making Connections

12. Concept Mapping

13. Applying Knowledge to New Situations

14. Creating a Scientific Explanation Using

Evidence

15. Focusing on Basics First

16. Using Themes to Organize Content

17. Clicker Questions (some)

18. Critical-Thinking Skill Activities

19. Formative Assessments (concept inven-

tories)

20. Case Studies

21. Dealing with Misconceptions

22. Constructivist Lessons (scaffolding

knowledge and skills)

23. Getting Students to Ask Questions and

Make Careful Observations

24. Focusing on How We Know

25. Using Stories to Learn about Science

is the recommendation to use themes in the

teaching of biology courses, themes such as

evolution or biological interactions, so that

whatever content is taught, students are able

to connect that information to a theme. This

allows students to form a framework for their

understanding of all biology. Finally, several

reports recommend that attention be paid to

the interdisciplinary nature of biology.

While the major science reform projects were

developed mostly in isolation from each oth-

er, they were informed by the same science

education literature; thus it is not too sur-

prising that there was convergence on some

of the central tenets for change. For instance,

the NGSS recommends that science education

should reflect real world interconnections (as

noted in #5 above); concepts should be inte-

grated with multiple core concepts throughout

(the use of themes); science concepts should

build coherently (scaffolding of skills and con-

tent); focus should be on application of con-

tent (applying knowledge to new situations);

and science education should coordinate with

mathematics standards (quantitative reason-

ing). Vision and Change from AAAS recom-

mended that courses “integrate core concepts

(themes) throughout the curriculum,” and

“integrate scientific process skills throughout

the course,” and that “fewer concepts should

be taught, but in greater depth.” Vision and

Change also recommended that the course be

inquiry-driven and introduce research experi-

ences as an integral component in the course.

As with other documents, Vision and Change

identified desirable student competencies,

including the abilities to: (1) apply the pro-

cess of science, (2) use quantitative reason-

ing, (3) use modeling and simulations, and

(4) tap into the interdisciplinary nature of

science. The AACU’s Liberal Education and

America’s Promise (LEAP) project identified

essential learning outcomes for students, such

PSB 63 (1) 2017

9

Announcements

as their ability to: (1) focus on Big Questions

(problem-solving) in society, (2) focus on in-

tellectual and practical skills, (3) practice pro-

gressively more challenging problem-solving

(scaffolding of skills), and (4) demonstrate

application of knowledge, skills, and respon-

sibilities to new settings and complex prob-

lems. In addition, included in the AACU’s

High-Impact Practices (HIPs) recommenda-

tions is the focus on undergraduate research

throughout the undergraduate program, cul-

minating in a capstone course or project that

requires a student to synthesize all that he/

she has learned and is able to do. Successful

participation in HIPs has been found to: (1)

increase the retention and graduation rates of

students, especially for historically disadvan-

taged students, (2) generate more positive stu-

dent attitudes about college, faculty, learning,

and themselves, and (3) increase self-reported

students gains in learning (Kuh, 2008). As a

HIPs Institute Faculty Mentor for the past four

years, I can attest to many changes institutions

around the country have seen in students after

they implement HIPs into their undergradu-

ate degree programs.

The last major project I would like to discuss is

the revision of the College Board’s Advanced

Placement (AP) science courses. These

courses are taught in high schools around

the country, but are designed to be similar to

a freshman-level undergraduate class. I was

the co-Chair of the AP Biology Development

Committee for the last eight years; this com-

mittee helped revise the AP Biology course,

to create a curriculum framework used by all

the AP Biology teachers (~12,000 teachers),

and to develop the new Biology exams. The

problem with the former AP Biology course

was that it was content-driven, and students

and teachers tried, unsuccessfully, to “cover”

an entire college biology text in complete de-

tail. The new course emphasizes a reduced

breadth of content and an increased depth of

student understanding while increasing the

use of essential reasoning and inquiry skills.

Also, there is now a major focus on “science

as a process” in the course, and content is

melded with science practice skills to create

student learning outcomes. The new AP Bi-

ology curriculum framework focuses on four

“Big Ideas” (themes) that inform the content

of the course: (1) evolution, (2) energy and

homeostasis, (3) information transfer, and

(4) interactions among organisms, systems,

and their parts. The seven Science Practices

(Box 3) have been adopted by all the new sci-

ence courses that AP offers, including biology,

chemistry, and physics, and serve as the foun-

dation for all the skills that students need to

possess.

The new AP Biology course emphasizes inqui-

ry-based and student-directed labs. Where-

as the old course had many teacher-directed

labs, in the new course, students generate

their own questions for investigation, and

design, conduct, and report on their own ex-

periments. Not only has the course changed

dramatically, the exam has too. No longer are

any low cognitive level, declarative knowl-

edge, recall questions asked, such as “What is

the name for this structure in the cell (with a

picture pointing to a chloroplast)?” Now, stu-

dents must engage with evidence—either with

evidence they produce by working with data

or with evidence that is provided to them—to

answer a question that incorporates both bi-

ological content and one of the seven science

practice skills. In addition, students are giv-

en six new “grid-in” questions, which require

students to work with data and then to pro-

vide numerical answers that they grid into a

template, without the benefit of any answers

from which to choose. The final new piece of

the exam are six short essay questions in addi-

tion to two of the familiar long essay questions

PSB 63 (1) 2017

10

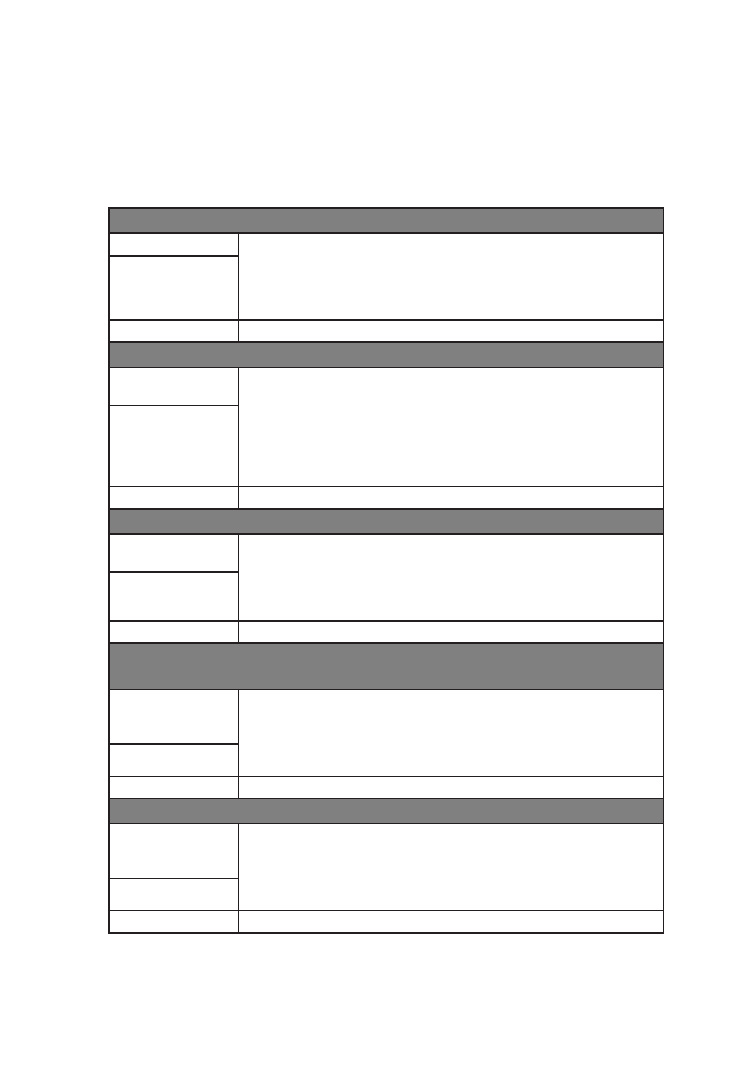

Box 3. Science Practices Adopted by

and Incorporated into Advanced Place-

ment (AP) Biology, Chemistry, and

Physics Courses

1. Use representations and models to com-

municate scientific phenomena and solve

scientific problems.

2. Use mathematics appropriately.

3. Engage in scientific questioning to ex-

tend thinking or to guide investigations.

4. Plan and implement data collection

strategies in relation to a particular scien-

tific question.

5. Perform data analysis and evaluation of

evidence.

6. Work with scientific explanations and

theories.

7. Connect and relate knowledge across

various scales, concepts, representations,

and domains.

that students must answer in the second half

of the exam.

The immediate impact of the new AP Biolo-

gy course was that 12,000 high school teach-

ers changed the way they taught biology at

the same time, and each May, approximately

250,000 students take the new exam. Many

teachers had to replace all their laboratory in-

vestigations or incorporate many more labs

into their course. They all needed to incor-

porate inquiry and mathematical activities

throughout their course, not just in a few

labs. On one of the old AP biology exams,

about 11% of the questions related to evolu-

tion, but because evolution is a theme of the

new course, approximately 35% of the ques-

tions on one new exam involved evolution.

In 2012, before the revision, about 19% of all

students received a “5” on the exam (highest

score), while 34.8% received a 1, and only 14%

received a 3. After the revision, about 5% of

students received a “5,” 7% received a “1,” and

“36% received a “3.” Thus, the old exam had

a bi-modal distribution of scores (with many

1s and 5s), which was an exam that rewarded

those who could memorize a lot of material,

even if they didn’t understand the material or

couldn’t design an experiment. The results

of the new exam show a normal distribution

of students with many fewer 5s and 1s and

many more students receiving an “average”

(3) score. To me, this indicates that we are no

longer just rewarding (or penalizing) students

based on their memory of a lot of biological

facts, but that AP Biology is now measuring

students’ ability to design experiments and to

apply, connect, explain, and use information

and data.

How BSA Can Influence

Educational Reform

Based on the information I have provided at

the beginning of this article and in Part 1, I

think there is growing acceptance of science

education as a research discipline. And, we

know what works in a classroom to help stu-

dents learn science and stay committed to

biology as a major. Finally, we know there is

continued relevance of plants in future basic

and applied research. So, it’s incumbent upon

us to integrate these factors as we work toward

solution to our educational problems. The

question is, “How can BSA help to influence

science education reform?” I have several rec-

ommendations.

First, we botanists need to keep educating stu-

dents, the public, and other scientists about

PSB 63 (1) 2017

11

the essential nature of plants to humans and

to the future research initiatives in the United

States. Also, if one of our goals is to get more

undergraduates interested in plant biology as

a viable career choice, then introducing more

students at the freshmen level to the wonders

of botany is important. We must encourage

the best botanical instructors to teach large,

basic courses, and support them when they do,

so that young undergraduates can be hooked

on botany before they choose a different path.

There are over 2,000,000 freshmen entering

U.S. colleges and universities each year (U.S.

Bureau of Labor statistics, 2016), and most of

these students are going to take an introducto-

ry biology course. If we can infuse more bot-

any into these courses, then we have a better

chance of having students take future botany

courses. Currently, over half of the students

take their introductory biology course at a

community college. So, if you have finishing

graduate students who are looking to enter the

teaching profession, then don’t neglect the op-

portunities at a 2-year institution. (At the 2016

annual conference, we invited faculty from re-

gional community colleges near Savannah to

attend a workshop on inquiry instruction that

was led by Marsh Sundberg, Catrina Adams,

and myself.) Another point about commu-

nity colleges is that their student populations

are extremely diverse, and if we value a BSA

with membership that reflects the diversity of

America, then we need to cultivate students

who begin their educations at these regional

institutions. (In terms of diversity, the BSA

has a wonderful program, PLANTS, that is

funded by NSF [A. Sakai and A. Monfils, PIs,

with BSA Staff, H. Cacanindin] and that has

been bringing a diverse group of undergradu-

ates to our annual meeting since 2010 [http://

botany.org/awards_grants/detail/PLANTS.

php]).

The higher education system in the United

States is unique in the world in that almost all

post-secondary institutions require students

Although we have a good

idea of what works in the

classroom and although

most faculty have heard

about some evidence-

based activities, few

faculty have the

knowledge or experience

to implement these

activities effectively. This

raises the importance

of faculty professional

development to inform

faculty of these methods

and to let them practice

and think about how

these practices would be

used intentionally in their

classrooms.

to take general education courses, including

at least a year of science, with one lab course.

Scientists often lament that this requirement

is really insufficient for any college graduate

entering a world that is impacted by science

and technology. However, one can also see

this as a half-full glass and a huge opportunity

to influence young undergraduates by placing

the best botanical instructors in general edu-

cation courses. For many students, including

future politicians, journalists, citizens, voters,

and some teachers, this may be the only bi-

ology course they ever take. In general, BSA

PSB 63 (1) 2017

12

should help botanists obtain faculty positions

in biology departments. Perhaps we can of-

fer mock job interviews and continue our re-

sumé-building workshops to help our grad-

uates gain faculty positions where they can

have influence on students and curricula.

We must encourage

the best botanical

instructors to teach

large, basic courses,

and support them when

they do, so that young

undergraduates can be

hooked on botany before

they choose a different

path.

Another important way that BSA can influ-

ence reform is if members improve our own

botany/plant biology courses, implementing

what we know works to help students learn

and focusing on competencies identified as

critical for student success. To help facul-

ty improve, BSA can offer additional faculty

professional development opportunities—not

just at BSA conferences, but at other meet-

ings and at individual institutions. Again, we

know that some BSA members are already

leading professional development activities

for faculty and graduate students—perhaps

we can advertise activities you are leading to

promote your work and provide greater ac-

cess to them. In terms of professional devel-

opment, one of the newest Research Coordi-

nation Networks for Undergraduate Biology

Education (RCN-UBE) projects is the Facul-

ty Developers Network (Deborah Allen, PI;

Uno, co-PI), and one part of this project is to

determine what scientific societies are doing

to help their members do a better job in the

classroom. BSA can contribute a lot to this

discussion.

One hidden aspect of getting more botanists

into introductory classes is the fact that AP

Biology conducts a “higher-ed validation”

study to determine what topics/concepts

should be included in the course. A list of po-

tential topics is sent to undergraduate faculty

who teach Introductory Biology courses, and

if insufficient numbers of them identify plant

topics as relevant to their course, these topics

will be eliminated from consideration for the

AP Biology curriculum. This kind of unex-

pected consequence of having botanists in the

right place at the right time can have a signif-

icant impact on what is taught in classrooms

all across the country. Consider working with

national educational testing services such as

the Educational Testing Service (ETS) to help

develop questions for the AP and SAT exams.

Getting more botanical questions on these ex-

ams means that pre-college teachers will de-

vote more time teaching about plants.

I think that BSA also needs to think about

ways to increase our outreach to the general

public. Perhaps we can cultivate secondary

members—for instance, amateur botanists or

other non-botanical professionals who are in-

terested in plants, the environment, and per-

haps even in basic plant research to become

members or attend our conferences? Can

we encourage more BSA members to offer

demonstrations and talks, and to lead field

trips for environmental groups, Native Plant

societies, gardeners, youth groups, and groups

such as the Botanical Society of Washington

(a long-standing forum for all things botani-

cal)? I know that many BSA members are al-

ready engaged in a number of such outreach

activities—perhaps we just need better adver-

tisement of these events so other members

can learn about what you are doing and to use

PSB 63 (1) 2017

13

your activity as a model.

I think that BSA must continue to collaborate

with other scientific organizations to promote

scientific and botanical literacy of our students

and the general public. BSA and the Ameri-

can Society of Plant Biologists (ASPB) have

collaborated on the development of “Core

Concepts and Learning Objectives in Plant

Biology for Undergraduates”

(http://

botany.org/file.php?file=SiteAssets/outreach/

botany-pbiologycoreconcepts.pdf).

In addi-

tion, we are currently working with the ASPB

and other plant societies in the Plant Science

Research Network, a network funded through

an NSF grant from the RCN program. The

purpose of the network is to discuss common

issues that all plant biologists may experience

as professionals, including issues related to

funding, publishing, graduate students, and

education.

We have a very good Education Department

whose work was recently rewarded with an

NSF grant to continue ramping up Planting-

Science activities. We must continue to sup-

port the work of the Education Department;

perhaps you would be interested in signing

up as a PlantingScience mentor? This depart-

ment has several other projects that have been

initiated or are being discussed, but this is an

area where more BSA members can become

engaged and more activities and projects can

be developed. Do you have any ideas or rec-

ommendations for the Education Department

and BSA?

I also think we need to engage more under-

grads in activities in our own departments

and to bring more students to our meetings so

they get hooked on plants and BSA at an early

point in their career. We can encourage and

engage students who are interested in bota-

ny by starting a BSA Student Chapter at our

own institution. Currently, there are only 19

such chapters in the United States. Informa-

tion about how these can be started is found

at: http://botany.org/students_corner/

chapters/.

Most importantly, I encourage each of you

to seek opportunities in which you can in-

crease your impact on students and col-

leagues, whether it is in your own classroom

or through projects at the national level or in

communicating science to the general pub-

lic. I urge you to think about how you can

promote plants and educational reform and

improve the botanical literacy for all, and I

would gladly accept suggestions from you for

how BSA can continue to have an impact on

students, botanical friends, and faculty col-

leagues. Thank you very much.

Literature Cited

American Association of Colleges and Universi-

ties. 2011. The LEAP Vision for Learning:

Outcomes, Practices, Impact and Employers’

Views. Washington, D.C.: AACU. 29 pp.

Brewer, C. A. and D. Smith, eds. 2011. Vision and

Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A

Call to Action. AAAS. 79 pp.

College Board. 2012. Advanced Placement Bi-

ology course: http://apcentral.collegeboard.com/

apc/public/courses/teachers_corner/2117.html?-

excmpid=MTG243-PR-21-cd

Kuh, G. 2008. High-Impact Educational Prac-

tices: What Are They, Who Has Access to Them,

and Why They Matter. Washington, D.C.: AACU.

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Sci-

ence Standards: For States, By States. Washing-

ton, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

PSB 63 (1) 2017

14

The

American Journal of

Botany welcomes your

collaboration in 2017

In an editorial in the January 2017 issue of the

American Journal of Botany, Editor-in-Chief

Pamela Diggle presented a current “state of

the journal” and extended an enthusiastic in-

vitation to BSA members and colleagues (po-

tential future members!) to contribute to the

success of the Society’s flagship journal.

Authors face many challenges in publishing

these days: the growing number of publishing

options, the importance of relating their work

to a broad audience, Open Access policies and

funder mandates, and changing data-sharing

and journal standards are just some of the

issues adding pressure on authors. This is all

beyond doing the actual research and then

undertaking the sometimes arduous process

of writing a manuscript, submitting it to a

journal, responding to reviews and revising

it, and hoping for acceptance. (Not all papers

are accepted at the first journal chosen, so

sometimes the paper is reworked for another

journal with differing requirements, different

reviewers, etc.) And then after the acceptance,

there is the expectation that authors will help

promote their work and communicate their

science, keep doing science, review papers

from other authors, perhaps teach, travel,

present at conferences, answer questions from

the public, speak up (or even march) for sci-

ence—and oh, yes, have a life!

AJB understands these challenges and wants

to work with its authors:

• We are a proud Society-owned journal;

• Our Editor-in-Chief is a well-respected sci-

entist with an impressive career, who is also

a fellow BSA member with experience in all

levels of publishing;

• We have a strong and expanding group of As-

sociate Editors (http://www.amjbot.org/site/

misc/edboard.xhtml) and reviewers from the

United States and around the world;

• We work hard for quick turnarounds (cur-

rently ~30 days) and rapid publication;

• We have a dedicated editorial staff who can

assist authors from pre-submission through

publication and post-publication promotion.

The journal succeeds when we receive strong

submissions with broad appeal to the botan-

ical community. We encourage you to sub-

mit your best work to your Society journal

at http://www.editorialmanager.com/ajb/de-

fault.aspx. We also encourage you to consider

submitting an essay to our “On the Nature of

Things” (OTNOT) series (send ideas direct-

ly to the Editor-in-Chief) and participating

in publications sessions, and conversations,

at the annual meeting. We are open to your

ideas for making your journal the go-to place

for botanical science.

PSB 63 (1) 2017

15

Look for the following AJB Special

Issues in 2017–2018:

• “The Tree of Life,” aimed at revisiting the

highly successful special issue on this topic

published in 2004 with the latest results yielded

up by phylogenomics and “big data”

• “The Tree of Death” on the critical importance

of the fossil record in understanding the

complete history of plants

• “Wood: Biology of a Living Tissue” based on

a highly successful symposium at Botany 2016

• “Patterns and Processes of American

Amphitropical Plant Disjunctions: New

Insights,” also based on a highly successful

symposium at Botany 2016

Dr. Diggle best summed it up in her editorial,

“As AJB begins its 104th volume, one standard

remains constant: our adherence to the mis-

sion of the Society and to serving our authors

with the highest standards. The American

Journal of Botany reflects what its authors and

reviewers choose to make it, so I encourage all

of you to ‘roll up your sleeves’ along with me

to maintain and increase the strength of our

society’s flagship journal as we enter 2017.”

Let’s do this!

Rapid publication with fast and thorough

peer review: Manuscripts are evaluated by

editors within a few days of submission and

are peer-reviewed by two to three outside re-

viewers. Average time to first decision is ap-

proximately 26 days.

Available in major indexes: APPS is included

in discoverability services including Web of

Science, Journal Citation Reports, PubMed,

WorldCat, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The

impact factor is 0.911.

Open Access: All APPS articles are Open Ac-

cess upon publication. OA fees are kept as low

as possible to help authors with limited fund-

ing. BSA members are charged US$450–800

per article (depending on length of member-

ship); non-members are charged US$1400 per

article.

Why publish your next methods paper in

Applications in Plant Sciences?

Society-published journal: APPS is pub-

lished by the Botanical Society of America,

which maintains rigorous standards of peer

review and is committed to working with au-

thors to strengthen their published research.

Research promoted on news and social me-

dia outlets: Press releases are prepared for

noteworthy articles, and articles are also pro-

moted on Twitter and Facebook, which have

over 24,000 combined followers. Research

published in APPS has attracted attention

from outlets including the National Science

Foundation’s Science360, CNBC, and Sci-

enceDaily.

APPS is a monthly, peer-reviewed, open ac-

cess journal focusing on new tools, technol-

ogies, and protocols in all areas of the plant

sciences. APPS is available as part of BioOne’s

PSB 63 (1) 2017

16

Open Access collection (www.bioone.org/loi/

apps).

Article types and detailed Instructions for

Authors can be viewed at http://www.botany.

org/APPS/APPS_Author_Instructions.html.

Please contact the editorial office (apps@bota-

ny.org) with questions.

-By Theresa Culley (Editor-in-Chief), Univer-

sity of Cincinnati

Editorial office contact: Beth Parada, Manag-

ing Editor, apps@botany.org

What do authors think about the ex-

perience of publishing in

APPS?

“Thank you for such a quick turn-around

on our submitted manuscript. This is the

most efficient journal editing any of the

authors have experienced!”

“I was impressed by the quality and speed

of your publishing services, and I am

looking forward to seeing the article in

press. “

“It has been a pleasure working with you

on this review article. We truly appreci-

ate your time and attentiveness and are

thrilled with the final result.”

“I just saw the press release for my paper

on ScienceDaily and all over the internet.

Thanks a lot!”

Press releases for recent articles published in APPS

Measuring trees with the speed of sound: http://bit.ly/2hYHZUD

Drones take off in plant ecological research: http://bit.ly/2f0YrS2

HybPiper: A bioinformatic pipeline for processing #pageenrichment data: http://bit.

ly/2ls5VkC

To view all of APPS recent press releases, visit http://botany.org/files/main/folder/

SiteAssets/publications/apps/press-releases.

17

SPECIAL FEATURE

By Pamela Diggle

Professor, Department of

Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology

University of Connecticut

L

ast year, I was honored to be invited by the

BSA Graduate Student Representatives,

Rebecca Povilus and Angela McDonnell, to

give the keynote presentation at the “Interac-

tive Career Panel & Luncheon” during Botany

2016 in Savannah, Georgia. They suggested

that I share my thoughts on choosing a career

in botany and on making the most of a degree

in the plant sciences. As I pondered what I

might have to contribute on those topics, I

realized that I didn’t really choose a career

in botany—it chose me. The most important

thing that I’ve learned along the way is to do

what you love, and #iamabotanist.

My passion for plants has dictated most of

my career and choices along the way. It may

sound trite or self-indulgent: do what you

love. But I find that by focusing on what I per-

sonally find most rewarding, I am at my most

creative and I have my best insights. It also

helps me withstand those long hours of things

that are not so fun (insert your most dreaded

task here), like the gazillionth plant part that

Careers Beyond the Academy

you have measured or weighed. But how does

identifying what you find rewarding translate

into a career?

As an academic at a research 1 university,

mentoring graduate students is part of my job.

And it is a terrific part of my job that has giv-

en me an opportunity to interact with amaz-

ing people who share my love of plants. Over

the years, however, I have come to understand

that not all students—creative, accomplished,

and driven as they may be—aspire to careers

in academia. I also realized, however, that

I was ill equipped to help graduate students

navigate the world outside of academia, given

that other than a brief interlude after college, I

have only ever been an academic. How can I

advise and mentor students who aspire to jobs

beyond the academy?

As I continued to contemplate this topic of ca-

reers in botany, and particularly jobs outside

of academia, I was struck by the juxtaposi-

tion of two articles published just over a week

apart in the New York

Times:

“So Many Re-

search Scientists, So Few Openings as Profes-

sors,” and “The Incalculable Value of Finding

a Job You Love.”

The first article, by Gina Kolata, highlights

Emmanuelle Charpentier, who is widely

known for her role in deciphering the mech-

anisms of the CRISPR-Cas9 system (https://

www.nytimes.com/2016/07/14/upshot/so-

many-research-scientists-so-few-openings-

PSB 63 (1) 2017

18

as-professors.html). She recently became the

leader of the Max Planck Institute for Infec-

tion Biology, but had spent the previous 25

years moving through non-tenure track po-

sitions, in nine institutions, in five countries.

The article paints a fairly gloomy picture of

the outlook for new PhDs. It focuses more on

biomedical science, which has been particu-

larly hard hit by job shortages, but resonates

across the life sciences. The article’s author

summarizes a commonly held view (emphasis

added):

“The lure of a tenured job in academia is

great—it means a secure, prestigious posi-

tion directing a lab that does cutting-edge

experiments, often carried out by under-

lings. Yet although many yearn for such

jobs, fewer than half of those who earn

science or engineering doctorates end up

in the sort of academic positions that di-

rectly use what they were trained for.

Others, ending up in industry, business

or other professions, do interesting work

and earn lucrative salaries and can con-

tribute enormously to society. But by the

time many give up on academia—four to

six years or more for a Ph.D., a decade or

more as a postdoc—they are edging to-

ward middle age, having spent their youth

in temporary low-paying positions get-

ting highly specialized training they do not

need.”

These kinds of statements encapsulate com-

monly held assumptions about graduate

school: they assume that being a professor and

researcher with a giant lab is the ultimate goal

of all graduate students, that anyone in any

other job is an inferior also-ran, and that ac-

ademia trains you for nothing but academia.

All of which, in my experience, are false and

didn’t merit much further thought. But I was

motivated to explore the last assumption, that

academia prepares you for only academia.

What kinds of preparation are employers in

non-academic professions looking for? In

all that I read, and in discussions with people

in the private sector and various government

agencies, I heard over and over again that it

is easy enough to learn hard skills on the job

(various lab techniques, for example), and for

many non-academics, the job they have did

not exist when they were in graduate school,

so they could not have trained for it anyway.

The critical skills that non-academic employ-

ers are looking for include:

• Initiative

• Creativity

• Leadership skills

• Organization

• Project management

• Budget and finance

• Communication, both written and spoken

• Social media creation management

• Flexibility

Clearly, completing and publishing your dis-

sertation research requires all of these skills

and more. But you have to be able to demon-

strate this to a prospective employer. Com-

ing up with a dissertation project requires

initiative and creativity, problem solving, in-

sight, and thinking on your feet. What are

some specific examples from your research?

Non-academic employers look at a CV very

differently than a search committee in aca-

demia and will want specific examples of each

of the attributes listed above. In this day of

PSB 63 (1) 2017

19

highly collaborative work, it is critical that you

clearly establish ownership and take the intel-

lectual lead on your dissertation research. You

need to be able to demonstrate that you know

how to ask and answer original questions and

follow through until you get an answer. What

experiences do you have that most clearly il-

lustrate these qualities?

Employers are looking for leadership skills.

Did you direct a team of undergrads? How

did you ensure quality control? How did you

deal with problematic students? Did you take

the lead in a collaboration? How did you ne-

gotiate maintaining leadership within a group

of peers?

Organizational skills. Have you managed

large data sets? Complex experiments? Bud-

get and finance? You raised grant funding and

managed the budget for your research. Com-

munication? You give seminars and write pa-

pers for publication. Many of you teach and

do outreach.

Flexibility! Flexibility was valued highly by

everyone I spoke with: be flexible in where

you might live, how you see yourself, what

you view as science, what might be fulfilling.

For example, I had an interesting conversation

with a Zeiss Microscope representative. He

has a PhD in microbiology and says he never

saw himself as a sales person (and was perhaps

a bit disdainful of this career). But as a grad

student, he became an expert on many differ-

ent types of microscopy, primarily through

troubleshooting and problem solving as need-

ed for his research. Now he has a career solv-

ing microscopy issues for others. His career

combines his deep knowledge of biology with

his talent for optics and problem solving and,

he says, it is deeply satisfying.

You certainly gain skills from your disserta-

tion research that are valuable well beyond

academia. But, beyond your research, I also

encourage you to do other stuff! Everyone I

spoke to about careers outside of academia

emphasized that networking is critical and so

Many faculty and

graduate students view

as ideal the research

fellowship that allows

you to devote your

attention to research full

time with no need for

the distraction and time

commitment of a TA.

This view is reminiscent

of a “trade-school”

mentality; that graduate

school trains you to “be”

a research scientist and

nothing else. I prefer

to think of graduate

school as an opportunity

to develop the kinds of

skills that you need for

the career you want.

is serendipity. Take advantage of opportuni-

ties to meet people and enhance your “soft

skills.” Serve as a teaching assistant, even if

you are not required to and even if you find

it difficult at first. Teaching enhances your

communication, management, organization-

al, and leadership skills. Go to department

seminars no matter what the topic and sign

up to meet with the speaker. If nothing else,

PSB 63 (1) 2017

20

the seminar will give you a greater knowledge

base that increases your ability to connect

with other people, and talking with the speak-

er will enhance your networking skills. And

you can never predict who that person knows.

Take a leadership role in something outside of

your department, such as a professional so-

ciety or an advisor to an undergraduate club.

Use LinkedIn to find people with interesting

jobs and ask them questions. Contact people

who do interesting things and ask if you can

shadow them for a day. People are generally

accommodating and often happy to be asked.

Take advantage of your university alumni as-

sociation to make contacts with people who

have interesting careers.

Many faculty and graduate students view as

ideal the research fellowship that allows you

to devote your attention to research full time

with no need for the distraction and time

commitment of a TA. And, many faculty ad-

vise their students not to get “distracted” with

extra courses or activities. This view is rem-

iniscent of a “trade-school” mentality; that

graduate school trains you to “be” a research

scientist and nothing else. I prefer to think of

graduate school as an opportunity to develop

the kinds of skills that you need for the career

you want.

Which takes me to the second article, which

I highly recommend: “The Incalculable Val-

ue of Finding a Job You Love” (https://www.

nytimes.com/2016/07/24/upshot/first-rule-

of-the-job-hunt-find-something-you-love-to-

do.html) by Robert H. Frank.

There are many thoughtful resources

concerning careers for PhDs in

academia and beyond.

A few of these include:

• The Chronicle of Higher Ed “Vitae”

section (https://chroniclevitae.com/

job_search/new)

• Nature and Science have jobs sections

with interesting essays on careers in

the sciences (http://www.nature.com/

naturejobs/science/news; http://www.

sciencemag.org/careers)

• Alumni associations and career ser-

vices at your university

• "Next Gen PhD: A Guide to Career

Paths in Science" by Melanie V. Sinche

(http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.

php?isbn=9780674504653)

You have already found something that you

love doing, or you would not be in graduate

school. For those of you who are consider-

ing career options beyond kinds of R1 institu-

tions where you are now, this article suggests

that rather than compiling a list of jobs that

are out there, think hard about what aspects

of graduate school bring you the most satis-

faction. When you are really “in the zone,” so

absorbed that you haven’t even looked at your

phone for hours, what are you doing? What

would it be like to do more of that? Then seek

out the kinds of experiences and contacts that

you will need for that career path.

21

SCIENCE EDUCATION

By Catrina Adams,

Education Director

BSA Science Education News and Notes is

a quarterly update about the BSA’s educa-

tion efforts and the broader education scene.

We invite you to submit news items or ideas

for future features. Contact Catrina Adams,

Education Director, at cadams@botany.org.

Over 2000 Students Conduct

Plant Science Investigations This

Fall Through PlantingScience.org

This past fall marked our largest Planting-

Science session ever. Thousands of students

worked with scientist mentors on their own

plant science investigations. Serving this

many students is only possible thanks to our

long-awaited new website, developed using

Purdue’s science collaboration platform HUB-

Zero. Thanks to all of our mentors, new and

experienced, who are volunteering their time

to inspire the next generation of plant scien-

tists. If you have been thinking about volun-

teering, next fall would be a perfect time to

join us. We’re expecting to double our num-

bers for fall, and we can use all the mentors we

can get. It’s a small time commitment, but you

can make a big impact on middle- or high-

school students. Most plant scientists had a

plant mentor at some point in their early lives,

someone who sparked an interest in plants

through their own enthusiasm. Through

PlantingScience you can be that plant mentor

that sparks a lifelong interest and enthusiasm

for plants. Sign up or direct your colleagues to

http://plantingscience.org/newmentor to sign up.

Congratulations to the Fall 2016 Star Project

teams (see the following page)! Each session

we choose 10 to 15 projects to feature in our

Star Project gallery. These projects represent

projects that have excelled in one of several

categories. Check out our Star Project Gallery

at https://plantingscience.org/starprojectgal-

lery to see what makes these 15 projects ex-

emplary.

Visit BRIT during Botany 2017

for a Tour or Workshop

The Botanical Research Institute of Texas

(BRIT) will be welcoming Botany 2017 at-

tendees to join them for a tour. Keep your eyes

on the schedule for times and details. Join

Gordon Uno and Marshall Sundberg for a

Sunday morning workshop, “Planting Inquiry

in Science Classrooms,” hosted at BRIT to learn

many practical techniques and activities you can

use to support your students’ active learning. At-

tendees at the workshop will receive a free print

copy of the book “Inquiring About Plants.”

PSB 63 (1) 2017

22

Science Education

Life Discovery Conference—

Data: Discover, Investigate, Inform

(October 19-21, 2017)

Please consider joining us at this year’s Life Discovery Conference, a stand-alone education

conference for high school and undergraduate biology educators. The 2017 conference will

be held at the University of Oklahoma. This year’s theme is on data and quantitative literacy,

and will feature a number of workshops, field trips, and short presentations around best prac-

tices and tested activities for bringing data into your classroom. Have an activity under development

yourself that you’d like to share? We’re accepting proposals for the Education Share Fair where you can share

your in-progress ideas and get feedback from your peers. This is a great conference for networking with others

passionate about biology education, and there is lots of time to get to know other participants. For more infor-

mation, visit http://www.esa.org/ldc/.

Hope to see you there!

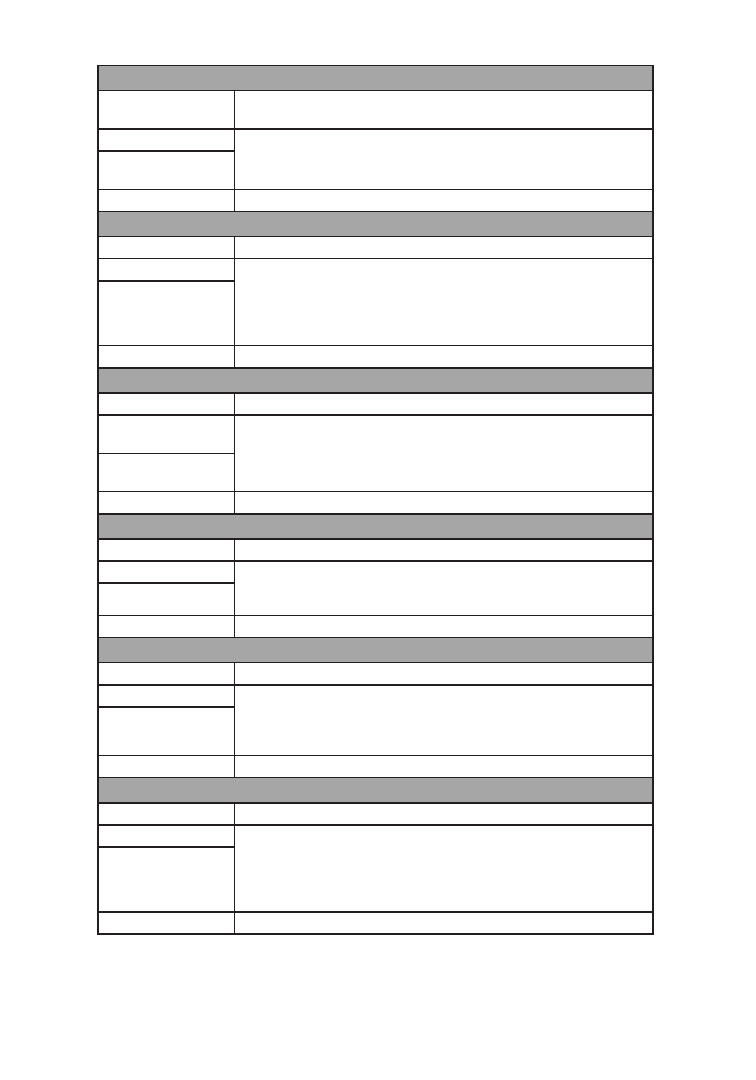

The “Power Plant Girlz,” one of 15 Star Project winners for the Fall 2016 Planting-

Science Session, conduct leaf disk flotation experiment around how different colors of

light affect photosynthesis. See more from the team on their Star Project Gallery Page at

https://plantingscience.org/spshingletonppg.

23

STUDENT SECTION

By Becky Povilus and James McDaniel

BSA Student Representatives

It’s a new year! You may be trying to figure

out what you can do in 2017 to help you reach

your education, research, and career goals.

Gathered here are upcoming opportunities

you might be interested in. Some deadlines

may have already passed, but they might be

things you’ll want to keep in mind for 2018!

We have four categories below for easy brows-

ing: Grants and Awards, Broader Impacts,

Short Courses and Workshops, and Job Hunt-

ing.

Round-up of Student Opportunities

Grants and Awards

Grants and awards can fund your research,

provide assistance for travel related to train-

ing or fieldwork, and even contribute to your

cost-of-living and tuition expenses (e.g., fel-

lowships). Additionally, applying for grants

and awards is a great opportunity to plan and

articulate your research. Lastly, remember to

check with your department or university for

internal grants that you can apply for.

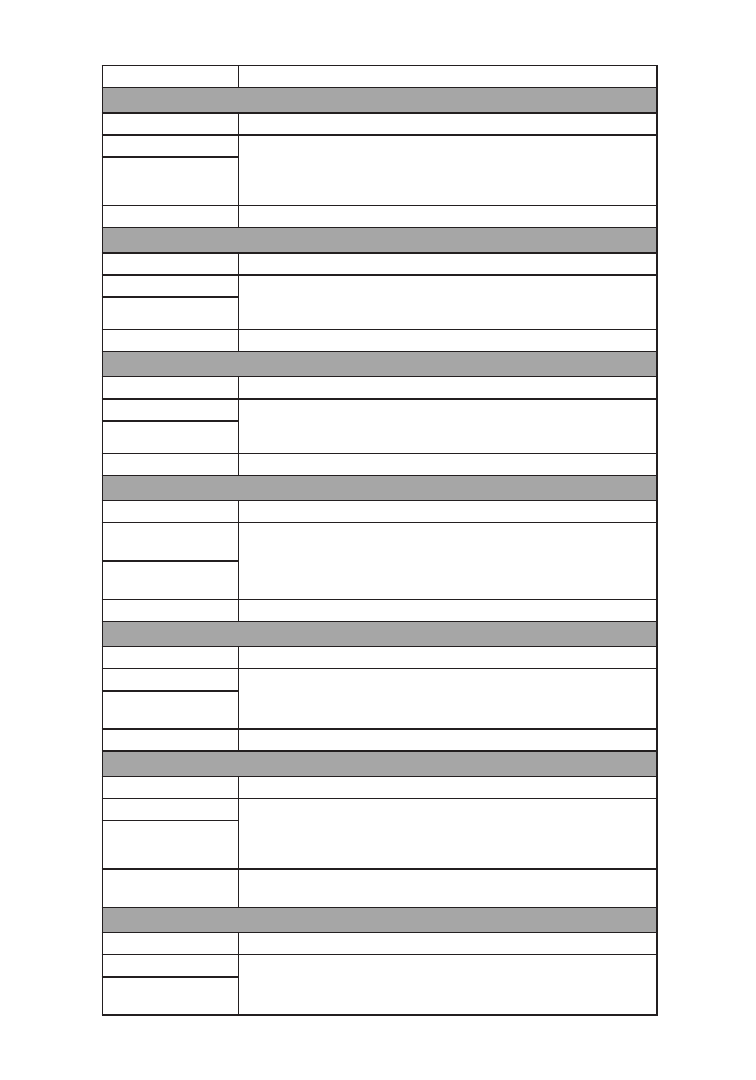

BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

$500

Botanical Society of America

Research Funds

Support and promote graduate student research in the botanical sci-

ences. Includes the J.S. Karling Award.

Deadline: mid-March

More info:

botany.org/Awards

BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards

$200

Botanical Society of America

Research Funds

Support and promote undergraduate research in the botanical sci-

ences.

Deadline: mid-March

PSB 63 (1) 2017

Student Section

24

More info:

botany.org/Awards

BSA Student Travel Awards

Variable, up to $500 Botanical Society of America

Travel (conference)

Several awards support student travel to the annual BOTANY con-

ference:

- Cheadle Student Travel Awards

- BSA Section awards

Deadline: early-April,

variable

More info:

botany.org/Awards

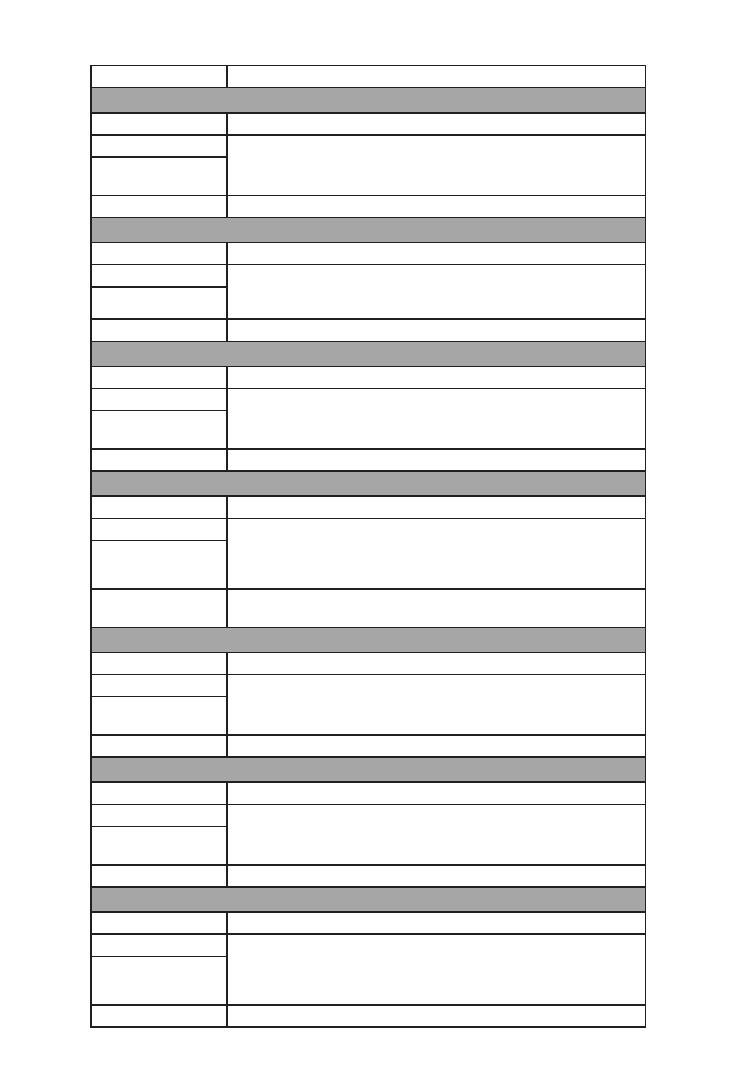

NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program

$32k/yr + tuition aid National Science Foundation

Stipend & Tuition

Support outstanding graduate students in NSF-supported disciplines

who are pursuing research-based Master’s and doctoral degrees at

accredited U.S. institutions.

Deadline: October

More info:

www.nsfgrfp.org

NSF Doctorial Dissertation Improvement Grant

up to $13,000

National Science Foundation

Research Funds

Provide partial support of doctoral dissertation research for improve-

ment beyond the already existing project (check that your project

falls within the scope of associated Divisions).

Deadline: October

More info:

Click the “Funding” tab at www.nsf.gov

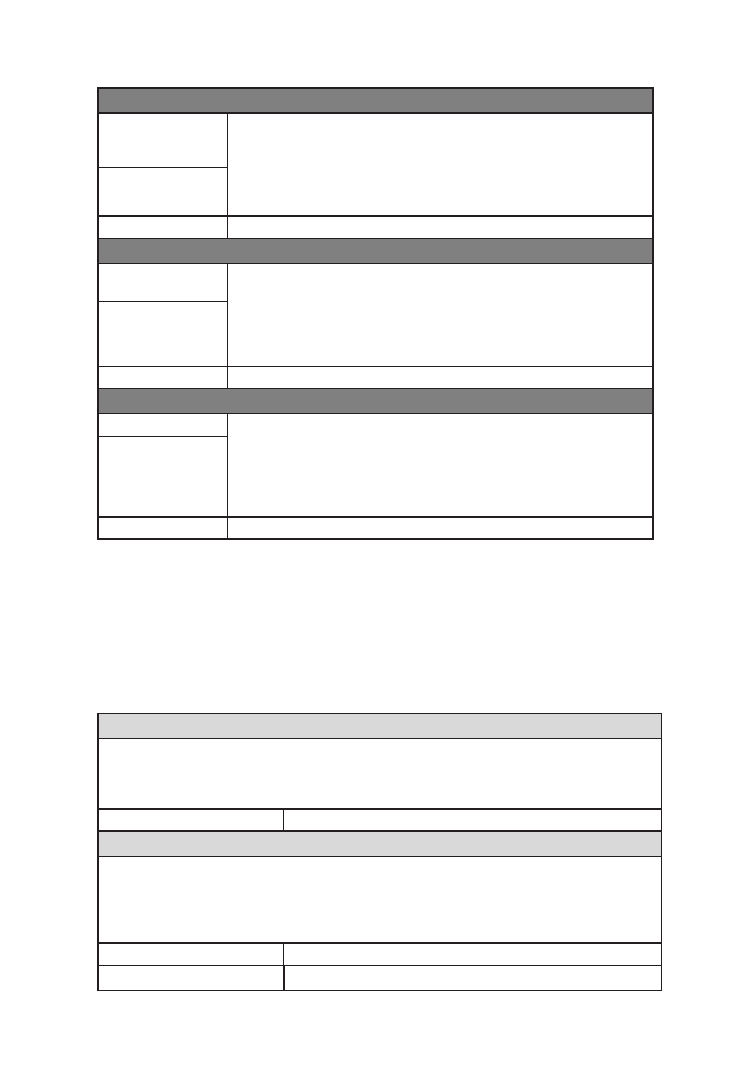

Torrey Botanical Society Fellowships and Awards

up to $2,500

Torrey Botanical Society

Research Funds &

Travel

Support research/education of student society members (fund field

work, recognize research in conservation of local flora/ecosystems,

fund course attendance at a biological field station). There are

awards for graduate students and undergraduates.

Deadline:

mid-January

More info:

www.torreybotanical.org

Prairie Biotic Research Small Grants

up to $1,000

Prairie Biotic Research, Inc.

Research Funds

Support the study of any species in U.S. prairies and savannas.

Deadline:

late-December

More info:

www.prairiebioticresearch.org

Botany In Action Fellowship

$5,000

Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

Research Funds

Develop new, science-based plant knowledge and chronicles tradi-

tional knowledge of plants. BIA promotes interactive scientific edu-

cation about the importance of plants, biodiversity, and sustainable

landscapes.

Deadline:

mid-January

More info:

https://phipps.conservatory.org/green-innovation/for-the-world/bota-

ny-in-action/call-for-proposals

The Lewis and Clark Fund for Field Research

up to $5,000

American Philosophical Society

Research Funds

Encourage exploratory field studies for the collection of specimens

and data and to provide the imaginative stimulus that accompanies

direct observation.

Deadline: early

February

PSB 63 (1) 2017

Student Section

25

More info:

www.amphilsoc.org/grants/lewisandclark

ASPT Graduate Student Research Grants

up to $1,000

American Society of Plant Taxonomists

Research Funds

Support students (both master’s and doctoral levels) conducting

fieldwork, herbarium travel, and/or laboratory research in any area

of plant systematics.

Deadline: early

March

More info:

www.aspt.net/awards

Richard Evans Schultes Research Award

up to $2,500

The Society for Economic Botany

Research Funds

Help defray the costs of fieldwork on a topic related to economic

botany, for students who are members of the Society for Economic

Botany.

Deadline: mid-March

More info:

www.econbot.org

Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research

up to $1,000

Sigma Xi

Research Funds

By encouraging close working relationships between students and

mentors, this program promotes scientific excellence and achieve-

ment through hands-on learning.

Deadline: mid-March

and October

More info:

www.sigmaxi.org/programs/grants-in-aid

Young Explorers Grant

up to $5,000

National Geographic Foundation

Research Funds

Support research, conservation, and exploration-related projects

consistent with National Geographic’s existing grant programs. In

addition, this program provides increased funding opportunities for

fieldwork in 18 Northeast and Southeast Asian countries.

Deadline: mid-March

and October

More info:

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/explorers/grants-programs/

yeg-application/

Systematics Research Fund

up to $5,000

The Systematics Association & The Linnean Society

Research Funds

Besides research focused on systematics, projects of a more general

or educational nature will also be considered, provided that they in-

clude a strong systematics component.

Deadline: Mid-Feb-

ruary

More info:

www.systass.org/awards

The Exploration Fund Grant

up to $5,000

The Exploration Fund Grant

Research Funds

Provides grants in support of exploration and field research for those

who are just beginning their research careers.

Deadline: mid Octo-

ber

More info:

www.explorers.org/expeditions/funding/expedition_grants

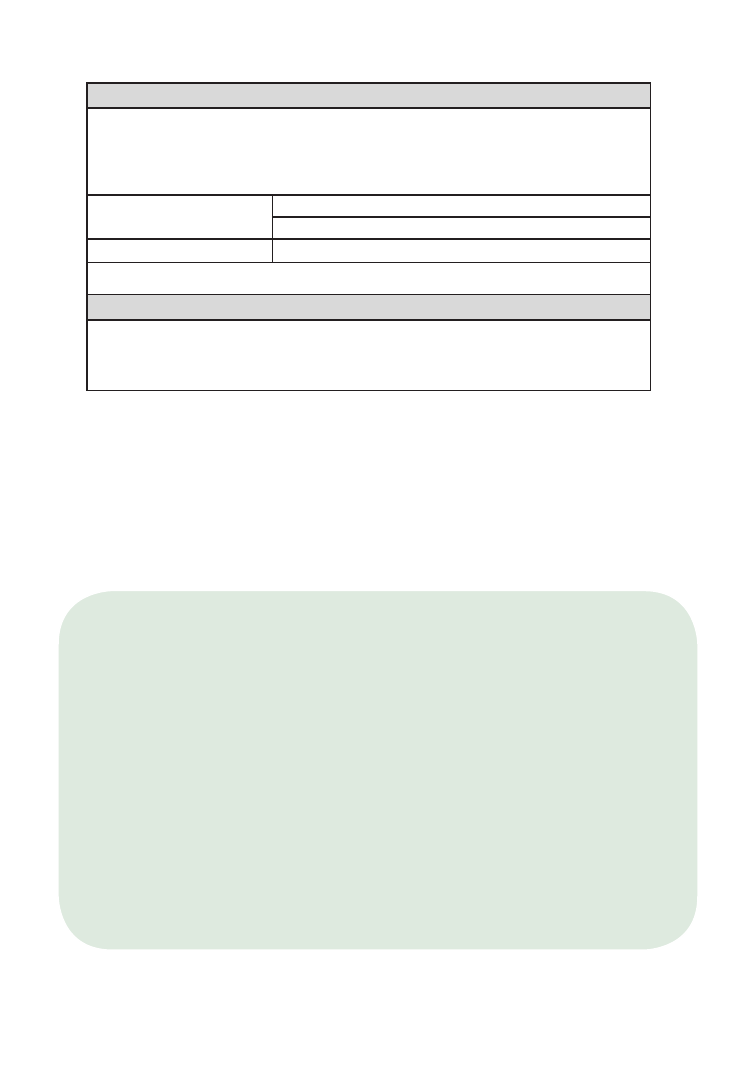

CIC Smithsonian Institution Fellowship

$32,700 for 1 year

CIC & the Smithsonian Institution

Stipend

One-year fellowships to support research in residence at Smithso-

nian Institution facilities. All fields of study that are actively pursued

by the museums and research organizations of the Smithsonian In-

stitution are eligible.

Deadline:

early-December

More info:

www.cic.net/students/smithsonian-fellowship

PSB 63 (1) 2017

Student Section

26

Ford Foundation Fellowship Programs

$24k-45k, for 1-3

years

Ford Foundation

Stipend

Three fellowship types are offered: Predoctoral, Dissertation, and

Postdoctoral. The Ford Foundation seeks to increase the diversity of

the nation’s college and university faculties.

Deadline:

late-November

More info:

http://sites.nationalacademies.org/pga/fordfellowships/index.htm

The Arnold Arboretum Awards for Student Research

$2,000-10,000

The Arnold Arboretum

Research Funds

Multiple awards or fellowships are offered for graduate students and

for undergraduates, with topics that focus on Asian tropical forest

biology and comparative biology of woody plants (including Chi-

nese-American exchanges). Check website for full information on

each award.

Deadline:

late-November

More info:

www.arboretum.harvard.edu/research/fellowships/

Garden Club of America Scholarships

$2,500-8,000

Garden Club of America

Research or Training

Funds

Many awards are offered to support botanical research, with foci

ranging from public garden history/use, field botany, medicinal bota-

ny, and horticulture. Check website for full information on each award.

Deadline:

January - February

More info:

www.gcamerica.org/scholarships

PLANTS Grant

Varies