P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

winter 2014 Volume 60 Number 4

In This Issue..............

Marsh Sundberg’s last issue as

editor of the PSB......p. 187

PLANTS Grant recipients and mentors at botany 2014

Applications accepted starting January 15!

The benefits of BSA membership....

p. 206

Address of BSA President Tom

Ranker at Botany 2014......p. 207

From the Editor

Winter 2014 Volume 60 Number 4

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 60

-

Marsh

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Biological Sciences, Ecology and

Evolution

University of Pittsburgh

4249 Fifth Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

kalecroy@gmail.com

Christopher Martine

(2014)

Department of Biology

Bucknell University

Lewisburg, PA 17837

chris.martine@bucknell.edu

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Botany &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Biology Department

Division of Health and

Natural Sciences

Holyoke Community College

303 Homestead Ave

Holyoke, MA 01040

cwetzel@hcc.edu

It’s that time of year again: preparing the last issue

(number 4) of a volume of Plant Science Bulletin. But

what to say? It’s a special issue for me---my last as

editor. First, thank you to Ann Antlfinger, Jenny Ar-

chibald, Nina Baghai-Riding, Doug Darnowski, Andy

Douglas, Norm Ellstrand, Vicky Funk, Dan Gladish,

Root Gorelick, Sam Hammer, Kathryn LeCroy, Chris

Martine, Jim Mickle, Mick Richardson, Beth Schussler,

Johanne Sharpe, Lindley Tuominen, Carolyn Wetzel,

and Andrea Wolfe who served on the PSB Editorial

Committee during the past 15 years of my editorship.

A lot has changed in the PSB, and the Society, during

that time. Beginning that first year, and with help of

Scott Russell, we began to make an HTML version of

each PSB available online. In the last 2002 issue, PSB

48(4), we announced that Bill Dahl was appointed as

the first Executive Director of the Society and that he

would be organizing the staff at a new office in St. Lou-

is. An early project was to digitize the entire previous

run of PSB to make it available online. Seven years

later, in PSB 55(4), we announced that beginning with

the first issue of 2010, articles for publication in PSB

would be peer-reviewed, thus providing a publication

outlet for members to publish scholarship not typi-

cally supported by the American Journal of Botany.

This also changed the duties of the Editorial Com-

mittee members, who assumed responsibilities as

monitoring editors of submitted manuscripts. A less

noticeable change in 2010 was a subtle reduction in

page size to better fit the format of electronic readers.

We instituted several dramatic changes in 2011. The

most obvious to the reader was the shift to a full-color

cover. More important, however, were production

changes with the BSA office staff assuming responsi-

bility for copyediting and layout (what a change in my

pre-publication schedule---thank you Rich, Beth, and

Johanne!). Despite these changes, the most important

thing about PSB has remained constant. As I noted

in my first editorial, the success of PSB “depends al-

most entirely on your input as [BSA] members and

contributors,” and it

will continue to do so.

I intend to be a faith-

ful reader and regular

contributor in the fu-

ture, and I hope you

will too.

185

Table of Contents

Society News

Judy Jernstedt Ends Tenure as AJB Editor-in-Chief .......................................................186

Marsh Sundberg Signs off as Plant Science Bulletin Editor ..........................................187

The

American Journal of Botany Centennial Celebration ends…

but its next century begins! .............................................................................................188

BSA Science Education News and Notes ....................................................

196

Editor’s Choice ............................................................................................

200

Announcements

In Memorium William A. Jensen 1927-2014 ................................................................201

Redesigned Hunt Institute Website at New URL ...........................................................203

WARF Innovation Award Winners Harness A Busy Virus,

Help Crops Bask In The Shade .......................................................................................204

BSA Membership: There’s No Place Like Home ...........................................................205

Reports

Evolution and extinction on a volcanic hotspot: Science, conservation, and

restoration in the endangered species capital of the world .............................................207

Book Reviews

Bryological and Lichenological ........................................................................................211

Economic Botany ...........................................................................................................213

Education ........................................................................................................................215

Systematics .....................................................................................................................217

Books Received ...........................................................................................

220

Shaw Convention Centre - Edmonton

July 25 - 29, 2015

Abstracts and Registration Sites open in February, 2015

www.botanyconference.org

186

“The Abominable Mystery,” and others on next-

gen sequencing, plant tropisms, global biological

change, and “Speaking of Food”: the connection

between basic and applied plant science), and the

successful celebration of the journal’s first 100

years (see the AJB Centennial Reviews published

throughout 2014, and items in the Plant Science

Bulletin). The 100th anniversary of the BSA and the

150th anniversary of publication of “On the Origin

of Species” also occurred during Jernstedt’s tenure.

It has been a good run—yet many challenges, and

opportunities, exist now and will into the future.

“

The biggest challenge has been trying to keep

up with the rapidly changing world of scientific

publishing and the increasing expectations of

authors and readers,” Jernstedt said. “It has been a

pleasure to work with the great group of thoughtful

and extremely diligent Associate Editors on the AJB

Editorial Board.

“I’ve been so impressed by AJB reviewers

—

their rigor, constructive approach, and

conscientiousness

—

and the hard-working Editorial

Office staff has been a true joy to work with all these

years. It was gratifying to see the AJB Impact Factor

creep slightly above 3 for 2010 (3.052), and I’m

confident AJB is in good hands to do this again!”

“BSA and the entire global community of

botanists has been fortunate indeed to have had our

flagship journal led by such an outstanding scholar

as Judy Jernstedt,” said current BSA President

Tom Ranker. “We are all greatly indebted for her

dedication and professionalism.”

Dr. Pamela Diggle, Professor and Associate

Head of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Department at the University of Connecticut

as well as recent BSA President, will take over as

Editor-in-Chief beginning in 2015.

There is no doubt that Jernstedt will remain

active in the BSA, after having also served as BSA

President in 2001 and Treasurer in 1997, earning

the BSA Merit Award in 2010, and serving as a

PlantingScience mentor. The BSA thanks Jernstedt

for her many years of service and looks forward to

her continued work.

Judy Jernstedt Ends Tenure

as AJB Editor-in-Chief

After serving as the editor-in-chief of the

American Journal of Botany for 10 years, Dr. Judy

Jernstedt has just completed her tenure at the end

of 2014.

Jernstedt, Professor

of Plant Sciences at

the University of California at Davis, oversaw

many changes in scientific publishing since

2005—including the evolution and continued

development of online publishing and manuscript

submission systems, the rise of Open Access

and Open Data as issues for exploration, and the

importance of helping authors promote their work,

through traditional and non-traditional (e.g., social

media) outlets. The AJB was recognized in 2009 by

the Biomedical and Life Sciences Division (DBIO)

of the Special Libraries Association as one of the

top 10 most influential journals of the past 100

years in the field of biology and medicine, which

speaks to the strong efforts of the AJB’s authors,

reviewers, and editors. Her good work has led

to higher impact factors, a greater involvement

of the journal’s editorial board, increased reader

commentaries and author responses within the

journal, a number of impressive special issues

(including one celebrating Darwin’s Bicentennial:

Society News

187

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

whose proceeds go to support the PlantingScience

online mentoring program. (Copies are available at

www.plantingscience.org.)

“We are all grateful for the extreme dedication

of Marsh Sundberg in continually producing one

of BSA’s most valuable resources,” said current BSA

President Tom Ranker. “Under his editorship, the

PSB has evolved into an instantly available source

of extremely useful information for all interested in

botany and education.”

Dr. Mackenzie Taylor, Assistant Professor,

Plant Reproductive Biology and Development, at

Creighton University, will serve as the new PSB

editor beginning in 2015.

The BSA is honored to have had Sundberg steer

the PSB over all these years and looks forward to his

continuing work within the BSA.

Marsh Sundberg Signs off as

Plant Science Bulletin Editor

Dr. Marsh Sundberg, as noted in the PSB

Editorial in this issue, will step down as PSB Editor

after having served for 15 years. Sundberg has

worked diligently to keep the PSB---published since

January 1955---relevant and interesting to readers

looking for information in botany, from BSA news

and awards, to peer-reviewed articles that aid in

teaching, to helpful book reviews. He also worked

to digitize the entire archive of the PSBs as well as

the transition of the PSB from more than just a

hard copy and PDF; it is also available in a flipbook

format that works seamlessly with e-readers.

Sundberg’s passion for botanical education has

been prominent throughout his time heading the

PSB; in fact, readers can look forward to the fourth

part in his ongoing series on botanical education

in a future issue of the PSB. He also co-authored,

along with Gordon Uno and Claire Hemingway,

the recently released book Inquiring About Plants:

A Practical Guide to Engaging Science Practices,

Marsh Sundberg with his wife Sara.

188

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

The

American Journal of Botany Centennial Celebration

ends… but its next century begins!

In planning for how to celebrate the journal’s centennial celebration in 2014, the AJB staff realized that

the focus had to remain on the core strengths that have sustained the journal since 1914: its research and

its contributing Society members. Throughout the year, the AJB has featured a series of AJB Centennial

Reviews---articles that have looked at key research from the past with a revamped and updated take to

find out where the field stands now and going forward. The following AJB Centennial Review articles are

already available and can be accessed for free:

• “Neurospora crassa: Looking back and looking forward at a model microbe” by Christine M.

Roche, Jennifer J. Loros, Kevin McCluskey, and N. Louise Glass [101(12):2022, 2014]

• “Ever since Klekowski: Testing a set of radical hypotheses revives the genetics of ferns and

lycophytes” by Christopher H. Haufler [101(12):2036, 2014]

• “The plastochron index: Still useful after nearly six decades” by Roger D. Meicenheimer

[101(11):1821, 2014]

• “The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: Dioecy, monoecy,

gynodioecy, and an updated online database” by Susanne S. Renner [100(10):1588, 2014]

• “Phloem development: Current knowledge and future perspectives” by Jung-ok Heo, Pawel

Roszak, Kaori M. Furuta, and Ykä Helariutta [101(9):1393, 2014]

• “The role of homoploid hybridization in evolution: A century of studies synthesizing genetics

and ecology” by Sarah B. Yakimowski and Loren H. Rieseberg [101(8):1247, 2014]

• “The polyploidy revolution then…and now: Stebbins revisited” by Douglas E. Soltis, Clayton J.

Visger, and Pamela S. Soltis [101(7):1057, 2014]

• “Plant evolution at the interface of paleontology and developmental biology: An organism-

centered paradigm” by Gar W. Rothwell, Sarah E. Wyatt, and Alexandru M. F. Tomescu [101(6):899, 2014]

• “Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants?” by Norman C. Ellstrand

[101(5):757, 2014]

• “Repeated evolution of tricellular (and bicellular) pollen” by Joseph H. Williams, Mackenzie L.

Taylor, and Brian C. O’Meara [101(4):559, 2014]

• “The voice of American botanists: The founding and establishment of the American Journal of

Botany, ‘American botany,’ and the Great War (1906-1935)” by Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis [101(3):389, 2014]

• “The nature of serpentine endemism” by Brian L. Anacker [101(2):219, 2014]

• “The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity” by Karl J. Niklas [101(1):6, 2014]

• “The American Journal of Botany: Into the Second Century of Publication” by Judy Jernstedt

[101(1):1, 2014]

To celebrate the contributions of the people behind the science, the PSB, throughout 2014, has featured

short interviews with some of the AJB’s most prolific contributors. This issue wraps up this special feature,

but note that many of these authors are still contributing to the journal, well into 2015!

The new year---and new century for the AJB---will bring some interesting changes and new features.

Incoming Editor-in-Chief Pam Diggle has a number of features in mind for 2015, and the journal will be

expanding its reach and exploring a new look. We look forward to the start of the next 100 years!

189

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Carol and Jerry Baskin

Carol and Jerry Baskin both joined the BSA in 1969 and have gone on to serve the Society in a variety of

ways, from Jerry’s tenure as program director in 1990 to Carol’s tenure as president in 1998. Each of them

earned the Society’s highest honor, the BSA Merit Award, in 2001, and they’ve contributed 28 articles thus

far to the American Journal of Botany over the course of their careers. They recently reflected on their work

in the AJB.

The first article you published in AJB was “Germination Ecology of Phacelia dubia Var. dubia

(interior) in Tennessee Glades” in 1971. Please take us back to that period; what were you studying/

most interested in at the time?

In the late 1960s-early 1970s, the main focus of our research was the ecological life histories of herbaceous

species. In such studies, timing of events in the life cycle such as flowering and seed germination are

investigated in relation to environmental conditions, especially the seasonal changes in temperature and

rainfall. The purpose of these studies is to gain a better understanding of how the study species is adapted

to its habitat. As we were doing life history studies, we became very interested in the seed dormancy/

germination phase of the life cycle and began to design experiments to determine what environmental

factors were required for dormancy to be broken and for the nondormant seeds to germinate. Thus, seed

germination ecology, or what controls the timing of germination in nature, was becoming a focal point of

our research when we published our first paper in the American Journal of Botany in 1971.

You have a long history of very productive mutual collaboration. How did this come about? How

have you sustained it over the years?

We began to collaborate on research when we were graduate students at Vanderbilt University in the

1960s. We went to the University of Kentucky (UK) in August 1968, where Jerry had a job as an Assistant

Professor in the Botany Department. Carol did not have a job, and could not find a teaching job in central

Kentucky, so we decided to work together as a research team. In 1999, Carol became a full Professor at

UK, with the exact same salary as Jerry – down to the last 12 cents. Jerry retired from UK in June 2011, but

he is still very much involved in paper-writing; Carol is still working at UK. Thus, we are still collaborating

and working together on manuscripts.

Over the years, we have collaborated with our graduate students, as well as seed biologists from many

different countries. Since 2005, we have been to China 12 times and have become heavily involved with

seed research there, resulting in many collaborative projects/papers.

Jerry and Carol Baskin, 1979.

190

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

expected that our interest in seed germination

ecology would lead to a compilation of information

on the world biogeography of seed dormancy, and

we certainly did not think that the information we

acquired could be used to help us better understand

the evolutionary origins and relationships of the

different kinds of seed dormancy.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which one or two stand out

above the others and why?

“Germination ecophysiology of herbaceous plant

species in a temperate region” from 1988 was an

invited “Special Paper,” and it was the first summary-

type paper that we wrote on seed dormancy and

germination. In this paper, we summarized our

own data on germination phenology (274 species)

and dormancy breaking experiments (179 species),

including winter annuals, summer annuals,

monocarpic perennials and polycarpic perennials.

From the experience of writing this paper, we

realized the value of synthesizing information on

seed dormancy and germination, and this was part

of our inspiration to write a book on seeds.

“Ethylene as a possible cue for seed germination

of Schoenoplectus hallii (Cyperaceae), a rare

summer annual of occasionally flooded sites”

from 2003—Schoenoplectus hallii is a rare summer

annual bulrush of eastern/central USA, and its

seeds germinate in depressions (often in cultivated

fields) in wet springs. It took 10 years to figure

out the seed germination ecology of this species.

Freshly matured seeds are dormant and require

the cold moist (but not flooded) conditions of

winter for dormancy to be broken. In spring,

the nondormant seeds will germinate if they are

exposed to relatively high temperatures, light,

flooding and ethylene (produced in the field when

soils are flooded). If any one of these requirements

is not met, seeds enter conditional dormancy

and must go through another winter before they

potentially could germinate. Thus, seeds live in

the soil for many years and only germinate when a

depression has water in the spring. Although seeds

of some species will germinate under the same

environmental conditions that break dormancy,

those of S. hallii require one set of conditions to

break dormancy and another set of conditions to

promote germination.

Your latest article in the AJB was “Temperature

regulates positively photoblastic seed

germination in four Ficus (Moraceae) tree species

from contrasting habitats in a seasonal tropical

rainforest” in 2013. Please tell us how the thread

of your research has changed over time.

Our early studies on seed germination ecology

were mostly conducted on herbaceous species

that grew in temperate eastern North America,

primarily Tennessee and Kentucky. We studied

species that grew in a wide variety of habitats,

including cedar glades and other rock outcrops,

forests, roadsides, fields and pastures. Eventually,

we worked in collaboration with people in other

parts of the USA and from other countries on

species outside our home range.

In the 1980s, while writing our book “Seeds:

Ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy

and germination,” we undertook a survey of

the world biogeography of seed dormancy and

collected information from all the major vegetation

types on earth; we had data for 3580 species. Since

publication of our book in 1998, we have continued

to collect information on the biogeography of

seed dormancy and in collaboration with many

colleagues continued studies on seed germination

ecology of species growing in various places.

A second edition of our book was published in

early in 2014, and it contains information for more

than 14,000 species. Information on the world

biogeography of seed dormancy has stimulated

us to have a deep interest in the evolutionary

origins and relationships of the various kinds of

seed dormancy (and nondormancy). Recently, in

collaboration with people in the National Center

for Evolutionary Synthesis (Duke University),

our data for about 13,000 species in 281 families

have been analyzed from a dormancy transition

perspective. Thus, we have expanded our research

interests from the timing of germination of seeds in

the cedar glades to middle Tennessee to the world

biogeography and evolutionary relationships of the

different kinds of seed dormancy.

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

We have consistently been interested in seed

dormancy/germination ecology. We never

191

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the journals in which you’ve published throughout your career?

We have long been members of the Botanical Society of America and think the American Journal of

Botany is a very good journal. Thus, when we published a paper in AJB we felt that our standing as

scientists was increased.

Jerry and Carol Baskin, 2012.

Tod Stuessy

Long-time BSA member Tod Stuessy (for the past

47 years!) has contributed over 30 articles to the AJB

in his career. Stuessy, a BSA Merit Award winner in

1999, shared his thoughts on the research over his

career.

The first article you published in AJB was

“

Chromosome Numbers and Phylogeny in

Melampodium (Compositae)

” in 1971. Take us

back to that period; what were you studying/most

interested in at the time?

My first article in the AJB was part of my

Ph.D. thesis at the University of Texas at Austin. I

continued working on aspects of the genus when

arriving at Ohio State in 1968, and in fact, we are

now still working on the group using molecular

methods. I remember very well the thrill of having

this paper published in AJB. It was sole authored,

as many papers were then, and I felt really proud to

have it in one of the mainstream botanical journals.

Your latest article in the AJB was “

Genetic

variation (AFLPs and nuclear microsatellites) in

two anagenetically derived endemic species of

Myrceugenia (Myrtaceae) on the Juan Fernández

Islands, Chile

” in 2013. How has the thread of

your research changed over time?

For the past 30 years we have been working on

the evolution and biogeography of the endemic

plants of the Juan Fernández (Robinson Crusoe)

Islands, off the coast of Chile. My interest in island

biology came from reading the book “Island Life”

by Sherwin Carlquist. It seemed to me then, and

still seems to me now, that these isolated land

masses would be great places to investigate the

process of evolution. Furthermore, there is a bit of

adventure working in isolated places, and the Juan

Fernández Islands are certainly that!

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

I have maintained an interest in the classification

and evolution of Compositae, and I have chosen

to work mainly in groups of the family in Latin

America, beginning in Mexico, then into Central

America, and finally in southern South America

into Argentina and Chile. Then there is my interest

in island biology already mentioned. I have also

maintained a strong interest in the principles and

methods of biological classification and continue to

publish on this topic.

192

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which one or two stand out

above the others and why?

Quite frankly, I don’t feel that any one of

the articles I published in the AJB is more

significant than the others. I think that this is

because I remember the persons and places that

accompanied these papers, and these are personal

recollections and have little to do with the science

in the papers themselves. I suppose that the paper

most cited is the one on Paeonies with Tao Sang

and Dan Crawford (“Chloroplast DNA phylogeny,

reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia

(Paeoniaceae)” from 1997).

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

As a botanist, I value my membership in the

Botanical Society of America. Hence, I also

value publishing in this journal, which has always

maintained a high (but not unrealistic) level of

quality.

Ruth Stockey

Oregon State University

Ruth Stockey has been a member of the BSA for

over 40 years and was presented with the BSA Merit

Award in 2006. She has just published her 32

nd

AJB

article, and she shared her thoughts on her research

over the years.

The first article you published in AJB was

“Seeds and Embryos of Araucaria mirabilis” in

1975. What were you studying/most interested in

during that period?

I wrote this article as a part of my Master’s

thesis. At that time, I was studying araucarian

conifers from the Cerro Cuadrado Petrified Forest

of Patagonia and collecting living araucarian

specimens in Australia and New Caledonia. My

detailed anatomical work on permineralized fossil

plants started during the 1970s, a theme that I have

continued in many of my papers since. Ironically,

in 2012 I published a paper (“Seed cone anatomy

of Cheirolepidiaceae (Coniferales): Reinterpreting

Pararaucaria patagonica Wieland”) with Ignacio

Escapa and Gar Rothwell on fossils from this same

site where we reinterpreted the material described

my third paper (“Reproductive biology of the Cerro

Cuadrado (Jurassic) fossil conifers: Pararaucaria

patagonica” in 1977). With the discovery of

new and better preserved fossils, we were able to

demonstrate that Pararaucaria was a member of

the extinct conifer family Cheirolepidiaceae and

provided the first anatomical description of cones

from this family that has been known mostly from

compression fossils lacking anatomical detail.

Your latest article in the AJB was

“Hughmillerites vancouverensis sp. nov. and the

Cretaceous diversification of Cupressaceae” in

2014. Tell us how the thread of your research has

changed over time.

My areas of research have changed considerably

over the past 35 years. I started with conifer

reproductive biology. Research on coal balls in

the early days changed to include compression/

impression fossils and permineralized cherts

from Alberta and British Columbia when I

moved to Canada. Fossil plants from the Jurassic,

Carboniferous, Cretaceous, Paleocene, Eocene

and Pliocene have been investigated. Upland

conifer fossils gave way to aquatic flowering plants

including Lythraceae, Araceae, Saururaceae,

Nymphaeaceae, and Limnocharitaceae, and finally

research on fossil ferns, bryophytes and fungi.

Dr. Tod Stuessy collecting plant specimens

at Laguna Laja, Chile, in 1988.

193

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

I expected to explore conifer research, which

evolved from studies of Araucariaceae to

Pinaceae, Podocarpaceae, Cheirolepidiaceae and

Cupressaceae. I never expected to study fossil fungi,

which turned out to be some of the best preserved

material in the Middle Eocene Princeton Chert

from British Columbia and our newer site at Apple

Bay.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which one or two stand out

above the others and why?

A couple of papers stand out in my mind because

of the interest they aroused, including “The role of

Hydropteris pinnata in reconstructing cladistics of

heterosporous ferns” in 1994 with Gar Rothwell

in which we demonstrated the monophylesis of

heterosporous aquatic ferns and the parent plant

for dispersed Parazolla spores. The plants were

rooted aquatic ferns with pinnate fronds that bore

spores inside bisexual sporocarps like Marsileaceae,

with spores like those of Salviniaceae.

Secondly would be the papers in the 2009

Darwin Bicentennial Special Issue that I co-edited

with Sean Graham and Peter Crane. For me,

“Distinguishing angiophytesfrom angiosperms: a

Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian-Hauterivian) fruit-

like reproductive structure” is a significant study

that will become more important when we describe

the entire structure (now found since the paper

was published). The seed containing structures

(“cupules”) are now known to be attached to axes

in compound cone-like structures with short

shoots in the axils of bracts. In turn, these short

shoots bear two leaves that wrap around single

tetrahedral seeds. The seeds were pollinated using

a pollination droplet and bisaccate pollen. Doylea

tetrahedrasperma will soon be placed into a new

order of gymnosperms.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

The journal has always been very highly regarded

in our field and now with “impact factors,” this

still remains true and can be quantified. I always

liked the quality of the illustrations, which in

paleobotany are extremely important. In addition,

time to publication has always been good.

Jack B. Fisher

University of British

Columbia

Dr. Jack Fisher has been a BSA member for nearly

50 years and earned the BSA Merit Award in 2003.

He has published in the AJB for the past 44 years,

and he spoke about his research and publications in

that time.

The first article you published in AJB was

“Development of the Intercalary Meristem of

Cyperus alternifolius” in 1970. Take us back

to that period; what were you studying/most

interested in at the time?

This was part of my PhD thesis, carried out in the

lab of Prof. Elizabeth Cutter, who was a pioneer in

the field of morphogenesis. It was the hot topic in

plant development at that time. I was interested in

the effects of plant growth regulators on monocots

and enjoyed experimental plant anatomy.

Your latest article in the AJB was “Gelatinous

fibers and variant secondary growth related to

stem undulation and contraction in a monkey

ladder vine, Bauhinia glabra (Fabaceae)” in 2014.

How has the thread of your research changed

over time?

Most of my career was spent as a researcher

at Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden, with

194

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

its excellent collection of tropical plant life. My

continuing interest was in plant development and

structure but emphasized topics of interest to the

Garden or in collaboration with other botanists-

--ranging from tree architecture, liana xylem

anatomy and hydraulics, to descriptive palm

anatomy. I always felt very lucky to be working in

a garden surrounded by fascinating plants and by

people who appreciated them.

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

In most of my studies, I’ve been drawn to

understanding how a structure develops into its

shape and what its function might be. Also, I have

a general love of microscopes and the beauty of

plant tissues. Perhaps my most unexpected area of

botanical study was tree architecture and computer

simulations of tree forms. This occurred only

because of a chance contact and later collaboration

with Hisao Honda, a Japanese biophysicist. We

complemented each other with a mix of botanical

and computer strengths.

Of all the articles you’ve published in AJB,

which one stands out above the others and why?

I value the paper on comparing the xylem of vine

and tree forms of Gnetum done in collaboration

with Frank Ewers (“Vessel Dimensions in Liana

and Tree Species of Gnetum [Gnetales]” in 1995)

because it was recognized with the BSA’s Michael

Cichan Award.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

First, to support the Botanical Society

of America as my professional society. But

equally, to have my work seen by colleagues

throughout the world who respect the journal.

The fine quality of the printing lets me present

my photomicrographs to their best quality.

Peter Raven

Peter Raven needs very little introduction! As

President Emeritus of the Missouri Botanical Garden

and a noted “Hero for the Planet” by Time magazine,

Dr. Raven has contributed nearly 30 articles to the

AJB throughout his career. Dr. Raven has been a

BSA member for 55 years, served as BSA President

in 1975, and earned the BSA Merit Award in 1977.

He spoke recently about his research in the journal.

The first article you published in AJB was

“

Chromosome numbers in Compositae I.

Astereae

” in 1960. Take us back to that period;

where were you, what were you doing, and what

were you studying/most interested in at the time?

When I was a graduate student at UCLA, I was

studying the Onagraceae, plants now referred to

the genus Chylismia, with Harlan Lewis; Mildred

Mathias, Daniel I. Axelrod, and Henry J. Thompson

were among the members of my committee. I was

busy with the group on which I was writing my

dissertation, but starting to branch out into broader

aspects of evolution in the family. M. Kurabayashi

visited Harlan’s laboratory in 1959-60, my last year

there, and we worked on the morphology of the

chromosomes in the family, publishing an article

describing how their morphology changed during

the course of meiosis and revealing patterns that

seemed to be correlated with the complex structural

heterozygosity in the family but which have not

yet been explained satisfactorily at a molecular

or structural level. At the same time, we graduate

students were counting chromosomes in the family

Asteraceae (Compositae) and finding interesting

Dr. Peter Raven while teaching at Stanford Univer-

sity in the 1960s.

195

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

patterns in number and morphology. I collected all

the species I could get my hands on, and with the

collaboration of Don Kyhos eventually published

a long series of articles including hundreds of new

chromosome counts.

Your most recent article in the AJB was the

introduction

to the

Special Issue on Biodiversity

in 2011. How has the thread of your research

changed over time?

What we used to call biosystematics, in which the

role of chromosome number and morphology was

of central importance, has become less fashionable

and fewer people know how to count chromosomes

or bother to do so---a pity. Now nucleic acid

analyses of sequences or even whole genomes

are stressed, to learn more much more efficiently.

The chromosome work is still valid, as is artificial

hybridization, which tells so much about the nature

of species in various groups of plants. Along the

way I collaborated a lot with Hiroshi Tobe, recently

retired as Chairman at the Botany Department,

Kyoto University, and

one of the runs of papers in

AJB

reflects that collaboration.

Since I moved from Stanford to the Missouri

Botanical Garden in 1971, I have focused more

on floristics, producing work not suitable for

publication in AJB, since floristics could be carried

out efficiently with the major herbarium and library

at MBG, and especially on conservation worldwide.

When I published my first paper in the journal, it

was not obvious that special efforts were needed for

conservation, whereas now it is completely obvious.

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

Plant systematics and evolution were my major

focus from the mid-1950s to about 1980, and

then I turned almost exclusively to floristics and

conservation, and finding support for others. I

had no idea until the mid-1960s that conservation

would become such an important part of my career,

and neither did anyone else, for the most part.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which one stands out above the

others and why?

The joint article with Lewis and Kurabayashi

on mitotic chromosomes in Onagraceae (“

A

Comparative Study of Mitosis in the Onagraceae

”

from 1962) seems to me to have been the most

important in that it began to solve a problem of

general importance. Others in AJB have mostly

been parts of large fields of knowledge.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

Excellent circulation, reputation, and format,

one of relatively few options when I began my

career, and now better than ever.

Dr. Peter Raven.

196

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Catrina

Adams, Acting Director of Education, at CAdams@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at psb@</p>

botany.org.

21

st

Century Challenge:

Opening Student’s Eyes to

Plants in Their World

—Dr. Catrina Adams, Acting Education Director, BSA

It is a warm fall day and I’m standing behind a

booth at the Missouri Botanical Garden’s popular

“Prairie Day” event running a classic outreach

activity: guess the natural object based on touch

alone. A 9-year-old gets a quizzical look on her

face as she reaches into the “mystery box.” She

takes the egg-shaped object in her hand, and runs

her fingers over the papery scales. “Oh!” she says,

“It’s an acorn!” Pulling the pinecone out of the box,

she confirms her guess with a smile, “Definitely an

acorn.” Now I’m the one perplexed—this is the third

child today making the same misidentification.

Perhaps you have noticed students arriving in

your botany classes with very little background

knowledge about plants. As Lena Struwe put it in

an interview for a recent article on Plant Blindness

in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Many times I have to

start from scratch. This is a petal. This is a leaf. This

is a branch.”

The September issue of CBE Life Sciences

Education has a special focus on plant science

teaching and learning and is well worth a read.

In the article “Attention ‘Blinks’ Differently for

Plants and Animals,” authors Benjamin Balas and

Jennifer Momsen apply the “attentional blink,”

an established paradigm in visual cognition, to

investigate differences in visual perception of plants

and animals. They find that plants do not capture

our attention in the same way as animals; it’s harder

to notice plants. The authors offer three ways

instructors can help students overcome perceptual

biases against plants:

1. Directly address plant blindness in instruction.

2. Increase opportunities for students to actively

attend to plants in their environment.

3. Present plant images simultaneously with text

or narration.

It’s not just students who are inattentive to plants.

Part of the problem is that many K-12 teachers do

not feel as prepared to teach about plants to their

students, and favor using animal examples to

address core concepts in biology. When surveyed

through Horizon Research’s National Survey of

Science and Mathematics Education about how

well qualified they felt to teach five fundamental

topics, high school biology teachers reported being

least confident about plant biology. Only 59% of

biology teachers report ever having had a course in

botany.

As botanists, we can make a difference by

building bridges between levels of education, and

by reaching out to younger audiences and their

teachers to share our passion for plants. What can

you do to help others pay attention to, appreciate,

and become curious about the plants that they

currently pass obliviously every day?

Could you share learning activities you’ve

developed with a broader audience through the

PlantED Digital Library?

Could you spare a few hours to communicate with

middle- and high-school student teams through

PlantingScience? Mentoring with PlantingScience

requires a small time commitment (about an hour

a week for 2-8 weeks when teams are active), with

a flexible schedule. The best part is that you don’t

need to leave your office to make a difference in

the lives of students and teachers from around the

world. We’re recruiting mentors for the upcoming

spring session until January 31. To register as a new

mentor, go to http://www.plantingscience.org.

Perhaps you are already doing outreach, having

broad impacts with your research, or volunteering

your time to local efforts. If so, please let us know

about your efforts so we can inspire other members

at cadams@botany.org!

We all know how critical plants will be to facing

this century’s global challenges. Let’s ground our

future leaders, professionals, and citizens with a

greener vision of the world around them and help

open their eyes to plants.

197

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Youngest Gardeners Learn to

Love Plants

Joan Hudson is passionate about bringing

plant awareness and appreciation to the youngest

audiences, volunteering her time to design and

deliver garden programs for pre-K 4- and 5-year-

olds at the Gibbs Pre-K Center of the Huntsville

Independent School District in Huntsville, TX. She

and the other garden volunteers there involve the

young students in experiencing the garden using all

five senses.

“I just love going to the preK and working with the

many students each week. They all have a smile

when they come to the garden… It is very rewarding

– they are the next generation.”

Members Share Their Passion

for Science and Plants by

Mentoring

“I am a very scientific-minded guy with new ideas

everyday. I’m always interested in how things work

and how things are put together. I am not a very

plant oriented student and I never thought about

planting anything in my life. I rest the future of

plants in your hands.” – Quote from Planting-

Science student to scientist mentor

Middle- and high-school years are an important

time to capture students’ interest in science and in

plants, which unfortunately are underrepresented

in many K-12 classrooms. During these years

students are doing a lot of self-identification,

finding their interests and beginning to think of

themselves as “good at science” or “not good at

science.” It’s a critical time to influence students

and break through negative stereotypes about

what science is and who scientists are, and give

them a taste of what it is like to practice authentic

science, including the creative thinking required to

troubleshoot experimental designs and make sense

of data.

This past summer we had the opportunity to talk

with several PlantingScience mentors, and asked:

“Why spend your time mentoring middle- and

high-school students online?”

Dr. Rupesh Kariyat of the University of Wyoming

was a mentor with Planting Science in the beginning

years and was excited with the opportunities it

offered not only the students, but also the science

community. He believes the program has the ability

to encourage students to study science. “I never had

such an opportunity to interact with a scientist,” he

said, “and to design and execute an experiment.”

“We get the cool science,” Kariyat said. “No other

science gets this opportunity.”

Klara Scharnagl, a mycologist with Michigan

State University, has been a scientist with Planting

Science for 2½ years, and enjoys infusing an

enthusiasm for plant science in the next generation.

She gets excited about engaging people in the

discussion of what they grow and eat. In the context

that people “generally don’t know the plants in

their own backyard,” Scharnagl says the important

discussion of loss of diversity is a long way off,

but botanists have a good place to start when they

can educate young people on the basics of plant

production.

One thing PlantingScience is particularly good

at, most of the mentors agree, is showing students

that scientists are real people.

“Children picture a scientist,” Scharnagl said,

“or some version of a scientist.” That image may

be Albert Einstein or any number of caricatures of

scientists shown in the media. Then the student

meets the botanist in PlantingScience via the

mentor’s online profile and conversation or Skype

and the image becomes more real.

“It changes what people think scientists are,

and we become real people with families, pets and

hobbies.” And, students get a real look at what

botany looks like as a career. That, say the scientists,

may have a real impact on whether students start

thinking about science as a future career choice.

Dr. Emily Sessa of the University of Florida is

enthusiastic about science outreach into all levels,

including elementary education. “It teaches

important skills, including critical thinking,” she

says. “If you give a little kid a microscope, it opens

up a whole new world. It might change their life. It

is really powerful if you introduce a child to science

at a young age.”

St. Louis University’s Dr. Allison Miller is also

convinced that plants can be a hugely important

vehicle for thinking about science, but even more

important, for how we think about life on the planet.

The connections among plants, conservation, food,

and society, she explains, have created a perfect

storm of information need that botanists can fill.

198

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Active young scientists like Angela Rein

McDonnell, the new student representative

on BSA’s Board, have stepped up to work on

PlantingScience. “I am interested in being a better

communicator and learning to explain complicated

things,” she said of the program.

Talking to the middle- and high-school students

is fun for her. “They are excited to hear what I think,

and that makes me excited.”

The program “grows an awareness of plants and

their value to the world,” explained McDonnell,

who herself was inspired by her father who grew a

large garden throughout her youth.

The chance to change science literacy in the next

generation is a bright beacon for botanists. Andrew

Schnabel of Indiana University South Bend says he

got involved in the PlantingScience program at its

inception, believing that “participation is important

for botany.”

“Most students coming into the university have

little background in plants. It will help if we can

get some younger children educated.” Part of that

education, Schnabel said, is showing them the

plethora of jobs that exist in botany. “There are

thousands of jobs for plant biologists.”

It’s just a matter of taking the opportunity to open

the discussion with the upcoming generations, say

these scientists.

(Thanks to Janice Dahl, Great Story!, for her help

with this segment.)

PLANTED DIGITAL LIBRARY: WE

NEED YOUR BEST RESOURCES

Many of you are already engaging your own

students with plants and have phenomenal

education resources that you’ve seen impact

the students in your classes. Why not spend an

afternoon polishing these stellar resources and

share them with a broader audience online? The

PlantED digital library is accepting submissions.

Share your best lessons with teachers and

professors around the world and get the satisfaction

of knowing you are impacting many more students

than you can reach through your own classes.

PlantED is a peer-reviewed library of teaching

resources. The peer-review process helps you refine

your resource with feedback from reviewers and

you will have a citable teaching resource when the

materials are published online. To contribute, visit

planted.botany.org.

Check out these recently

published resources from the

library:

Chemical Competition in Peatlands

Jon Swanson, Edwin O. Smith High School

Jessica Budke and Bernard Goffinet, Univer-

sity of Connecticut

These lab exercises were designed to enhance

students’ understanding of the concept of chemical

competition in ecology. They use the moss

Sphagnum to illustrate the concept, which shows

students that competition occurs between plants.

Phylogenetic Approach to Teaching

Plant Diversity

Phil Gibson and Joshua Cooper, University

of Oklahoma

Educators can use this resource as an opportunity

for students to collect structural data that can be

used to construct phylogenies, combine structural

and molecular data to construct phylogenies, gain

experience in phylogeny construction, and provide

a meaningful framework to learn the characteristics

of major terrestrial plant groups.

TOOLS FOR 21

st

CENTURY

BIOLOGY TEACHING

What is 21

st

Century Biology?

The Keynote Panel at the recent Life Discovery

Conference aimed to answer that question and to

challenge us meet 21st century biology teaching

challenges. You can view a pdf of the presentation

here: http://www.esa.org/ldc/wp-content/

uploads/2014/10/2014-LDC-Keynote.pdf

Panelists Janet Carlson and Susan Singer

brought together biology education reform efforts

from K-12 and higher education to show the

common themes. As they demonstrate, “weaving

meaningful connections across STEM learning is

beginning to echo across all levels of education.”

The panelists challenged us to see STEM focus not

as content-specific, but rather as epistemic – “the

sources, strategies, or practices from which science

knowledge comes and, in turn, is shared.” In other

words, we should be focused on communicating

the “how” of biology, not the “what.”

199

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

The Keynote ended with a call to action. You can

be an agent of change by:

1. Crossing boundaries between K-12 and

institutions of higher education, talking with each

other and respecting each other’s strengths.

2. Being ready for students coming from a Next-

Generation Science Standards background who are

primed to understand cross-cutting themes and the

practices of science.

3. Thinking differently about undergraduate

biology: revisit core ideas in increasing depth,

build connections between ideas and disciplines,

carefully construct a storyline and help learners

construct and build explanations using evidence.

A Pedagogical Framework for

Screencasting

Some of you may have participated in the

Coursera MOOC “An Introduction to Evidence-

Based Undergraduate STEM Teaching,” a seven-

week course this fall that explored effective

teaching strategies for college STEM classrooms. If

you missed the course, this video series by Robert

Talbert of Grand Valley State University, developed

as a part of the course, describes the pedagogical

framework for screencasting as part of a flipped-

instruction model. If you’ve considered presenting

lectures outside of your classroom for any reason,

you may find this video a helpful resource: http://

tinyurl.com/k3efayr.

Inquiring About Plants

Don’t miss Uno, Sundberg and Hemingway’s

“Inquiring About Plants: A Practical Guide

to Engaging Science Practices,” which offers

classroom-tested “tricks of the trade” for drawing

students into the practice of science. All proceeds

from the sale of the $10.95 e-book will benefit the

PlantingScience program. Print copies are available

with a donation. For details or to get your copy, see

http://www.plantingscience.org.

www.plantingscience.org

200

Editor’s Choice

What Does Online Mentorship of Secondary Science Students Look Like?

By Adams, Catrina T. and Claire A. Hemingway.

2014. BioScience 64(11): 1042-1051.

Abstract:

Mentorship by scientists can enrich learning opportunities for secondary science students,

but how scientists perform these roles is poorly documented. We examine a partnership in which plant

scientists served as online mentors to teams conducting plant investigations. In our content analysis of

170 conversations, the mentors employed an array of scaffolding techniques (encouraging; helping clarify

goals, ideas, and procedures; and supporting reflection), with social discourse centrally embedded and

fundamental to the mentoring relationship. The interplay of techniques illustrates that scientist mentors

harmonize multiple dimensions of learning and model the integration of science content and practice. The

mentors fulfilled self-identified motivation to promote their students’ interest and to enculturate students

to the science community through online discourse. The patterns of this discourse varied with the mentors’

gender, career stage, and team–mentor engagement. These findings address research gaps about the roles,

functions, and conceptions of scientists as online mentors; they can be used to guide program facilitation

and new research directions.

201

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Personalia

In

Memorium

William A. Jensen

1927-2014

Dr. William August “Bill” Jensen, Ph.D., 87,

passed away quietly on September 9, 2014 at the

Sanctuary Facility in Dublin, Ohio after a long

illness.

Bill led a very distinguished and full

professional life. He received his Ph.B. (1948),

M.S. (1950) and Ph.D. (1953) all from the

University of Chicago. During his Ph.D. he held

Atomic Energy and Public Health predoctoral

fellowships at the University of Chicago and

Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Just before he began his undergraduate program at

the University of Chicago, Bill was drafted into the

service at the end of the World War II. He never

saw active duty but worked in an army hospital lab.

He continued in the reserves during his schooling

and returned to Europe to the Carlsberg Lab (with

Prof. Heinz Holter) in Copenhagen where he

completed his Ph.D. research. During his graduate

work he married his first wife Joan Sell and they

explored Europe and this set the stage for his future

love for travelling to many places in the world.

Upon returning from Europe, he carried out

postdoctoral work at the California Institute of

Technology (with Profs. Arthur Galston and

James Bonner) (1953-55) and in the laboratory

of Prof. Jean Brachet in Brussels, Belgium (1955-

56). He then accepted an Assistant Professorship

at the University of Virginia (1956-57) and then

the same at the University of California, Berkeley

(1957) where he quickly rose through the ranks

to Professor of Botany. During his tenure at UC-

Berkeley, he held positions of Chairman of the

Department of Botany and also of Instruction in

Biology, as well as Assistant and Associate Dean

of the College of Letters and Science. In 1973-

74, he was Program Director of Developmental

Biology at the National Science Foundation. Bill

was invited to move to Ohio State University,

Columbus in 1984 where he became Dean of

Biological Sciences (1984-1999) and Professor

of Plant Biology until his retirement in 2009.

Bill was a man of many talents and interests. His

early professional interests were in the areas of

cell differentiation associated with plant embryos

and embryo sac development which led him to

combine techniques of histochemistry and electron

microscopy, pioneering approaches at that time.

From this work he became a sole author of the

still popular book Botanical Histochemistry (1962).

He mentored numerous graduate students and

postdoctoral fellows who hold and have held major

teaching and research positions at institutions of

higher learning in the United States, Canada and

Europe. His research has been published in over 100

articles in a variety of excellent journals, including

14 articles in the American Journal of Botany.

Throughout his career, he developed a passion for

teaching at both the graduate and undergraduate

levels and received several important awards for

these efforts from the University of California and

the Ohio State University and the Charles E. Bessey

Award from the Botanical Society of America. At

the Ohio State University in his later years he taught

very popular large classes to non-science majors

that enjoyed his portrayals of famous scientists

and his multimedia presentations. His authoring

202

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

of entry-level texts in General Botany and

General Biology supported this love for making

botany and biology fun and understandable.

Bill gave generously to professional societies such

as AAAS, the Botanical Society of America, and

the American Institute of Biological Sciences.

He was a Fellow of AAAS and the California

Academy of Sciences, and received the Merit

Award (Distinguished Fellow) from the Botanical

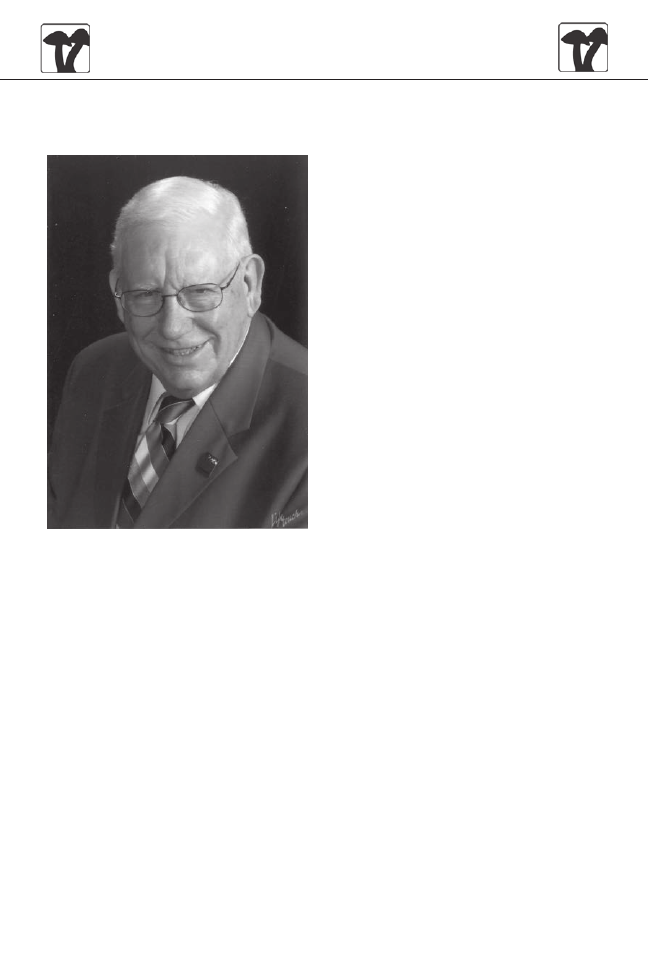

Society of America where he served in a variety

of capacities including its President in 1978.

From an early age when he joined the high

school science club because of his interests

in biology, botany and microscopes, as well

as playing the clarinet, to his adult life where

biology, botany and microscopes continued to

be focal points, Bill was always enthusiastic,

curious, questioning, and pushing-the-envelope

kind of person who loved challenges and always

expected the best from himself and others.

His insatiable curiosity and talent for creating

beautiful, abstract, color pen drawings of images

he had studied with his electron microscope

became his passion in later years. He loved doing

them, displayed them at art shows, sold them and

sometimes gave them away as gifts. Prof. Jensen, ‘Bill’,

you lived a full life, trained, mentored and taught

countless young people to love botany and biology.

You did this with dignity, humor, humbly and with

a deep-seated love for humankind. Such a legacy

will live on through your dear wife Beverly, your

family, friends and colleagues for many years to

come. We will miss you.

---Dr. Jack Horner

Dr. and Mrs. Jensen exhibiting his artwork at Botany 2013 in New Orleans.

203

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Redesigned Hunt Institute

Website at New URL

PITTSBURGH, PA—All things must come to

an end. Although huntbot.andrew.cmu.edu has

served the Hunt Institute well since 1997, it is time

for a change. With our redesigned and reorganized

website, we are migrating to a new URL (www.

huntbotanical.org).

We conducted a site-wide content review and

reorganization and turned to Mizrahi, Inc. (www.

mizrahionline.com) of Pittsburgh for a new look

and a better way to maintain and update the site.

Most of the content from our old site has been

incorporated into the new one. The reorganization

and new design just make it more accessible. Also,

we have augmented the new site with exciting,

additional content. All issues of Huntia, our journal

of botanical history, and the Bulletin, our newsletter,

are now available online as PDFs. Other relevant,

out-of-print publications will be added soon.

Descriptions are available for every exhibition since

our first public one in 1963. Publicity images and

checklists will be added to these Past Exhibitions

pages in the coming months. We added Virtues and

Pleasures of Herbs through History to the Exhibitions

Online section and revamped Botanists’ Art. Order

from Chaos will be undergoing a content review

and redesign in the future. Our existing databases

have been upgraded. We are pleased to announce

the launch of the long-awaited Archives’ database,

Register of Botanical Biography and Iconography.

We continue to add thumbnail images to the

Catalogue of the Botanical Art Collection at the

Hunt Institute database. The public domain images

will soon be available in a separate database to speed

downloading. Our marketing information has been

collected in an aptly named section where we invite

everyone to “Get Involved” with the Institute.

About the Institute

The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation,

a research division of Carnegie Mellon University,

specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of

plant science and serves the international scientific

community through research and documentation.

To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains

authoritative collections of books, plant images,

manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides

publications and other modes of information

service. The Institute meets the reference needs of

botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists,

librarians, bibliographers and the public at large,

especially those concerned with any aspect of the

North American flora.

Hunt Institute was dedicated in 1961 as the

Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt Botanical Library,

an international center for bibliographical

research and service in the interests of botany

and horticulture, as well as a center for the study

of all aspects of the history of the plant sciences.

By 1971 the Library’s activities had so diversified

that the name was changed to Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation. Growth in collections

and research projects led to the establishment

of four programmatic departments: Archives,

Art, Bibliography and the Library. The current

collections include approximately 24,000+

portraits; 200+ archival collections; 29,504

watercolors, drawings and prints; 243,000+ data

files; and 30,429 book and serial titles. The Archives

specializes in biographical information about, and

portraits of, scientists, illustrators and all others in

the plant sciences and houses over 200 collections

of correspondence, field notes, manuscripts and

other writings. Including artworks dating from

the Renaissance, the Art Department’s collection

now focuses on contemporary botanical art and

illustration, where the coverage is unmatched. The

Art Department organizes and stages exhibitions,

including the triennial International Exhibition

of Botanical Art & Illustration. The Bibliography

Department maintains comprehensive data files on

the history and bibliography of botanical literature.

Known for its collection of historical works on

botany dating from the late 1400s to the present, the

Library’s collection focuses on the development of

botany as a science and also includes herbals (eight

are incunabula), gardening manuals and florilegia,

many of them pre-Linnaean. Modern taxonomic

monographs, floristic works and serials as well as

selected works in medical botany, economic botany,

landscape architecture and a number of other

plant-related topics are also represented.

204

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

WARF Innovation Award

Winners Harness A Busy Virus,

Help Crops Bask In The Shade

Plant research reigns at the

annual prize ceremony

MADISON, Wis. – A discovery that could

transform drug production and a fresh strategy for

feeding a hungry world have claimed top honors

from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation

(WARF). The winning teams are led by professors

Aurelie Rakotondrafara and Richard Vierstra.

“We give these awards to recognize the creativity

and dedication that spark breakthroughs on

campus,” says Carl Gulbrandsen, managing director

of WARF.

This year’s prizewinners included a special

genetic sequence that could enable researchers to

produce multiple proteins from a single strand of

mRNA. The sequence, a type of internal ribosome

entry site (IRES), was discovered in a wheat virus

by UW–Madison plant pathologist Rakotondrafara

and collaborator Jincan Zhang.

“The new IRES is the first of its kind that can

be exploited in plant systems, with far-reaching

implications,” says Rakotondrafara. “The power to

express multiple genes at once could lead to better

biofuel crops and new drugs.”

The researchers found the special sequence

in the Triticum mosaic virus, which can express

its protein at a higher efficiency from its single

mRNA strand. Their discovery could change how

biopharmaceuticals are made, like the antibody

cocktail produced in tobacco plants currently being

used to treat Ebola victims.

A team led by genetics professor Vierstra also

received accolades for its work on light-sensing

plant proteins called phytochromes. These

photoreceptors play a key role in how plants

respond to shade, triggering developments such as

lanky stalks and immature fruit.

But phytochrome mutations created by Vierstra,

Ernest Burgie, Adam Bussell and Joseph Walker may

alter how plants react to their environment. That

could mean smaller crops capable of flourishing

in dense, low-light conditions, or making plants

flower and produce fruits and seeds at times of the

year when the weather might be better.

“To feed a surging world population, we’ll have

to rethink how we grow food,” says Vierstra. “This

research could be a major boon to agricultural

productivity.”

An independent panel of judges selected the

winners from a field of six finalists. These finalists

were drawn from among more than 400 invention

disclosures submitted to WARF over the past 12

months. The winning inventions each receive an

JOB OPENING

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR: BOTANY

Nine-month, tenure-track position, Department

of Biological Sciences, Emporia State University,

Emporia, KS. Ph.D. required by time of hire. Teach

plant taxonomy and lab, general biology, and

specialty courses that complement our existing

offerings at the undergraduate and graduate

level. Successful applicants will have experience

in plant systematics, plant community ecology,

or biogeography. Teaching experience desirable;

post-doctoral research experience desirable but not

required. Development of active research program

involving undergraduates and master’s-level

graduate students expected. Faculty typically teach

12 contact hours (or equivalent).

Starting date August 2015; Salary range: $50,000-

$53,000. Screening will begin January 13, 2015, and

continue until position is filled.

Send letter of application with separate statements

of teaching philosophy and research interests, CV,

unofficial transcripts, and four references including

address, telephone number, and e-mail address

to: Dr. Brenda Koerner, Search Committee Chair,

Department of Biological Sciences, Campus Box

4050, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS

66801-5415. Telephone: 620-341-5606; FAX: 620-

341-5607; e-mail: bkoerner@emporia.edu; website:

http://biology.emporia.edu.

An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity

Employer Institution, Emporia State University

encourages minorities and women to apply.

205

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

BSA Membership: There’s No

Place Like Home

There’s no place like home if you’re a botanist.

And if you’re a botanist, there’s no place quite as

comfortable as the Botanical Society of America—

at least that’s what the scientists at Botany 2014 in

Boise, Idaho, had to say.

“I love BSA and the Botany Conference. It really

feels like family,” said Klara Scharnagl, a mycologist

from Michigan State University. “It is friendly,

open and people are willing to talk about ideas.”

She talked about the interesting mix of relaxed

professionalism, and the focus of BSA on building

up young scientists.

Dr. Marian Chau of the University of Hawai‘i

at Manoa Lyon Arboretum first got involved as

a student and said the welcoming atmosphere

hooked her. “You can walk up to anyone, even the

big names, and they will talk to you about their

research and yours,” she said. That genuine interest

in all kinds of botanical science and in scientists

at all career levels are things many BSA members

believe is unique about the Society.

“Plants are my life,” said Dr. Uromi Goodale of

Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanic Garden, Chinese

Academy of Sciences. “I couldn’t think of a better

conference to attend.” She’s been a member of BSA

and attending the conferences throughout her

career, focusing on development, networking and

training.

“I think it’s my responsibility, not only as a

scientist, but as a human being to mentor young

people willing to conserve and preserve what I call

‘green gold,’ the plants and water,” she says. Like

so many of her fellow scientists in BSA, she takes

that feeling to heart, spending every moment of the

Botany Conference talking and mentoring, hoping

to help take science to the next level through the

emotional connections made with people.

Dr. Kyra Krakos, Maryville University, sees BSA

as a way to turn science up a notch, from the student

right on up. She brings her own students to the

conferences to “introduce them to a broader world

of science without terrifying them. Attending (the

conference),” she says, “is when students decide

whether to go on into science or not.” Or even, she

explains, exactly where in science they might want

to go.

Krakos talks passionately about the effect BSA

has on its young people. “They speak science

better” after they come to a meeting. “They make

connections and contacts, and they make decisions

about their careers and course of study.”

For Dr. Emily Sessa of the University of Florida,

BSA is a fantastic place to find plant scientists with

different backgrounds and fields of scientific study.

“From the moment I leave one Botany Conference,

I am counting down the minutes to the next Botany

meeting,” she said with a laugh. “It’s a contagious

sort of environment.”

Why contagious? It’s a combination, she

says, of taking into account the education and

camaraderie. Sessa first came to BSA on a research

award as a graduate student, and talks about all the

opportunities that exist at all levels for scientists.

Dr. Allison Miller of St. Louis University’s

Biology Department echoes that sentiment,

coming to BSA as the winner of the Young

Botanist award as an undergraduate. Today, she

has a network built of friends from those first years,

with new friends added each and every year. “It

is a friendly, supportive and honest environment,

not competitive,” she said. “It becomes a place of

support, not only professionally, but personally. “

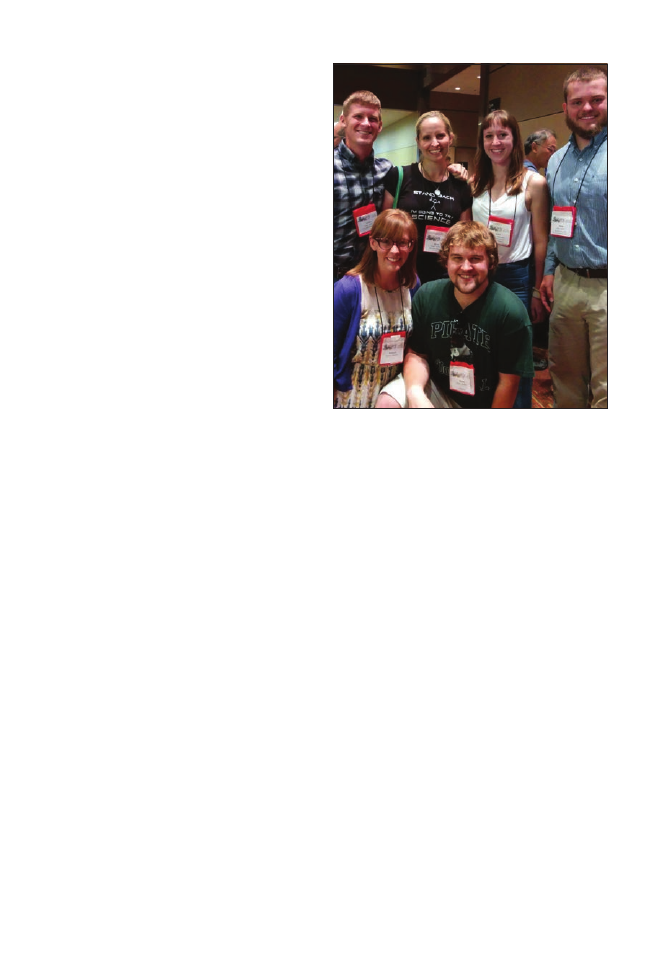

BSA member Kyra Krakos, University of Maryville-

St. Louis (top row, second from left) enjoying time

with some of her undergraduate students at Botany

2014: Adam Hoeft, Audra DeMariano, Adam Rork,

Ryan Hulsey, and Rebecca Girresch.

206

Plant Science Bulletin 60(4) 2014

Miller, like others, talked about the culture of

support and mentoring in the Society. “We all have

a huge responsibility to encourage a support people

through the rocky times and all the way through

their careers,” she said. “I have scientists here I seek

out even now. It is my responsibility to mentor

young scientists and my desire to seek out mentors.”

Networking is one way to start finding the people

who will impact your career, said Dr. Stacey Smith

of the University of Colorado, Boulder. “I always tell

my students, ‘The interview starts now.’ And it does.

As soon as you start connecting, all the foundations

you need through your career are right here at the

meeting,” she said.

“This is the group of people I am most comfortable

with,” Smith says. It has put her in contact with