P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Summer 2012 Volume 58 Number 2

In This Issue..............

BSA Board Student Representatives

visit Capitol Hill...pp. 44

It’s the season for awards....pp. 38

BSA election results...pp. 51

BSA Legacy Society Celebrates !...pg ??

BSA’s Highest Honor Goes to...

2012 Merit Award Winners......page 38

From the Editor

Summer 2012 Volume 58 Number2

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 58

Root Gorelick

(2012)

Department of Biology &

School of Mathematics &

Statistics

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler

(2013)

Department of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

(2014)

Department of Biology

Bucknell University

Lewisburg, PA 17837

c

hris.martine@bucknell.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Department of Biological Sci-

ences & Biochemistry Program

Smith College

Northampton, MA 01063

Tel. 413/585-3687

-Marsh

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

The day after the last issue of PSB arrived in hard

copy, I had a telephone call from an old friend, Hugh

Iltis. Hugh has been weakened by strokes and his voice

lacks the volume he used to project, but his passion is

undiminished. He wanted to inform me of the typo in

Peter Raven’s printed address (see Erratum, p. 38) but

also to take issue with what he felt was a major omission

related to human population growth—its underlying

cause. Hugh’s issue was that Peter did not mention

the need for any kind of birth control, which is a main

factor responsible for population growth. Of course,

population growth was not the focus of Peter’s article so

it is not surprising that he did not elaborate on it. On

the other hand, Hugh had a point that we frequently

overlook. We, as botanists, tend to focus on the

immediate problem of feeding people while protecting

the environment, but this is a Band-aid solution to the

underlying problem of human population growth itself.

The discussion with Hugh reminded me that we have an

educational opportunity, and with our science majors

I feel we have an educational obligation, to emphasize

the limits as well as the power of science in solving the

problems we face as a society. Peter focused on what

we can do as botanists to alleviate the ever-increasing

need for feeding more people, but in a sustainable

way. Hugh would argue that by limiting ourselves to

these solutions we are only making the problem worse.

Together they illustrate that science, by itself, will not be

able to solve the problem. There are ethical, religious,

political, and economic factors that provide a context

for science; it is our role as science educators to teach

both the power and limits of science and to be open

to dialogue with professionals trained in other ways of

knowing. We should be teaching this to our students

and demonstrating it by example.

This is a perfect segue to the report in this issue by

our student members on their recent trip to Capitol

Hill. One purpose was to inform legislators of the

importance of maintaining support for plant science

and young scientists may

be our best advocates.

But, it is also important

for our student advocates

to be aware of alternative

viewpoints and to report

back innovative ways

of supporting botany in

a larger perspective. It

is our job as faculty to

cultivate this awareness.

37

Table of Contents

www.botanyconference.org

Erratum .........................................................................................................38

Society News

Awards ..............................................................................................................................38

BSA Student Activists Visit Capitol Hill .........................................................................44

2012 Triarch “Botanical Images” Student Travel Award Winners ...................................47

BSA Science Education News and Notes

PlantingScience . ..............................................................................................................48

Education Bits and Bobs ................................................................................................ 49

Editors Choice Reviews

................................................................................50

Personalia

BSA Election Results ......................................................................................................51

Past-President Karl Niklas Named One of “Best 300 Professors” ...................................51

Meetings and Conferences

The Legacy Society Celebrates! ......................................................................................52

Celebrating 30 Years of the Flora of the Bahamas:

Conservation and Science Challenges ....................................................................... 54

Missouri Botanical Garden Ethnobotanists Receive National Geographic Society Grant ..

For Study At Crow Creek Indian Reservation .............................................................56

Special Lecture at Botany 2012 . ..................................................................................... 57

Announcements

Four Prominent Botanical Institutions Announce

Plans to Create First Online World Flora ...................................................................58

Reports and Reviews

Blanche and Oakes Ames: A Rela tionship of Art and Science .. ......................................60

Book Reviews

...............................................................................................65

Books Received

............................................................................................75

38

Society News

Erratum

From “Saving Plants, Saving Ourselves”: p. 3,

column 2, line 5. “ …reach 7 million by next spring

(April, 2012)…” should read “…reach 7 billion by

next spring (April, 2012)….”

The Botanical Society of

America’s Merit Award

The Botanical Society of America Merit Award is

the highest honor our Society bestows. Each year,

the Merit Award Committee solicits nominations,

evaluates candidates, and selects those to receive

an award. Awardees are chosen based on their

outstanding contributions to the mission of

our scientific society. The committee identifies

recipients who have demonstrated excellence

in basic research, education, public policy, or

who have provided exceptional service to the

professional botanical community, or who may

have made contributions to a combination of these

categories. Based on these stringent criteria, the

2012 BSA Merit Award recipients are:

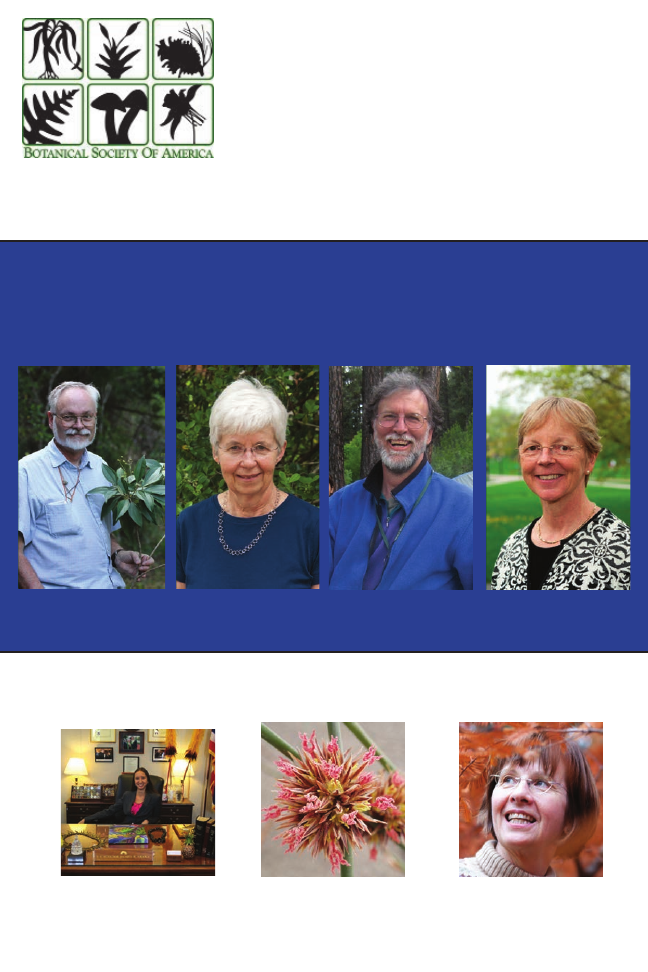

Dr. Patricia Gensel

University of North Carolina

Dr. Gensel is an international leader in the

investigation of early land plant evolution. Her

research, including rigorous field and laboratory

work, has contributed significantly to our

understanding of plant diversity at the time when

major lineages of land plants were emerging.

Through careful morphological and anatomical

investigations she has brought “to life” extinct

genera of early land plants and improved our

understanding of the ecosystems in which these

plants participated. She is active as Professor of

Botany at the University of North Carolina, where

she has taught since 1975 and has encouraged and

collaborated with many students and colleagues

internationally. Pat served as president of the

Botanical Society of America in 2000–2001,

during a time of great transition as the Society

began managing its annual Botany conferences

independently of AIBS.

Dr. Walter Judd

University of Florida,

Gainesville

Dr. Judd is recognized worldwide for his

contributions to plant systematics, taxonomy,

and phylogenetics. Although he is very well

known for his academic achievements, where he

has focused on the systematics of the Ericaceae

and Melastomataceae, as well as floristics in the

southeastern United States and the West Indies,

Dr. Judd is also an accomplished teacher, where

39

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

at the University of Florida, he has been awarded

numerous times for his excellence in pedagogy. He

also has taught an internationally renowned class

in tropical botany for the past 30 years at Fairchild

Tropical Botanical Gardens and The Kampong in

Miami. Dr. Judd is the lead author of the influential

textbook, Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic

Approach, which has been adopted throughout the

world as a model for teaching plant systematics and

taxonomy. Dr. Judd’s passion for teaching, research,

as well as learning, is ever influential to the graduate

and undergraduate students he mentors. The 2012

BSA Merit Award is a much-deserved honor for Dr.

Judd.

Dr. Richard Olmstead

University of Washington

Dr. Olmstead is recognized for his outstanding

contributions to reshaping the field of plant

systematics, including his leadership on the use

of chloroplast data in phylogenetic inference and

angiosperm classification. His doctoral research

with Melinda Denton resulted in a monograph of

the Scutellaria angustifolia complex (Lamiaceae).

His subsequent research on Asteridae has resulted in

major realignments in our understanding of family

boundaries in Lamiales (especially Lamiaceae and

Scrophulariaceae). He has published influential

papers on a broad range of issues in systematics.

Dick has guided the careers of numerous

undergraduates, graduates, and postdoctoral

fellows, fostered extensive collaborative

research activities, and made significant service

contributions to botanical and systematic societies.

The integration of his excellent research program

with public outreach activities through the Burke

Museum of Natural History and Culture and the

University of Washington herbarium serve as a

model for how we should be sharing our botanical

knowledge to improve the world.

Dr. Allison Snow

Ohio State University

Dr. Allison Snow is recognized for her outstanding

contributions to botanical science in the areas

of basic research, education, and professional

service. Allison’s research on pollination biology,

gene flow, and risk assessment of transgenic crops

represent significant contributions to the field. She

has mentored a number of students and researchers,

and has been a strong advocate for communicating

the importance of botany to the general public

via the media. Finally, Allison has been deeply

involved both nationally and internationally in

service to a variety of organizations, including the

National Academy of Sciences, the World Trade

Organization, and as president for the Botanical

Society of America.

40

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

Darbaker Prize

The Darbaker Prize in Phycology is given each

year in memory of Dr. Leasure K. Darbaker. It

is presented to a resident of North America for

meritorious work in the study of microscopic

algae based on papers published in English by the

nominee during the last two full calendar years.

This year The Darbaker Award for meritorious

work on microscopic algae is presented to:

Dr. Walter Adey, National Museum of Natural

History, Smithsonian Institution. Dr. Adey has been

a pioneer of modern phycology. His development

of modern coralline taxonomy and the structural

analysis have provided the underpinnings for our

present understanding of this group that is now

being enhanced by molecular methods. He has

further pioneered the system of using filamentous

algae as scrubbers toward clean water production

and biofuels generation.

Dr. Sabeeha Merchant, University of California

at Los Angeles. Dr. Merchant has been instrumental

in developing the genetics and genomics

of Chlamydomonas as a model organism. Her work

has elucidated the role of metabolic cofactors and

iron and copper utilization in the biogenesis of the

photosynthetic apparatus, thus providing the basic

understanding of chloroplast development for

green algae and plants.

Vernon I. Cheadle Student

Travel Awards

(BSA in association with the Developmental and

Structural Section)

This award was named in honor of the memory

and work of Dr. Vernon I. Cheadle.

Allison Bronson, Humboldt State University.

Advisor: Dr. Mihai Tomescu. Botany 2012

presentation: “A perithecial sordariomycete

(Ascomycota) of diaporthalean affinity from the

Early Cretaceous of Vancouver Island, British

Columbia (Canada).” Co-authors: Ashley Klymiuk,

Ruth Stockey, and Alexandru Tomescu.

David Duarte, California State Polytechnic

University, Pomona. Advisor: Frank Ewers.

Botany 2012 presentation: “Plastic responses of

wood development in California black walnut

(Juglans californica): Effects of irrigation and post-

firegrowth.” Co-authors: Frank Ewers, Edward

Bobich, Shawn Pham, and Kristin Bozak.

Rachel Hackett, Central Michigan University.

Advisor: Dr. Anna Monfils. Botany 2012

presentation: “Prairie fen plant biodiversity: The

influence of landscape factors on plant community

assemblages.” Co-authors: Hillary Karbowski and

Anna Monfils.

Matthew Ogburn, Brown University. Advisor:

Dr. Erika Edwards. Botany 2012 presentation:

“Anatomy of leaf succulence in the clade

Portulacineae + Molluginaceae: Evolutionary

jumps into novel phenotypic space.” Co-author:

Erika Edwards.

Triarch “Botanical Images”

Student Travel Awards

This award provides acknowledgment and travel

support to BSA meetings for outstanding student

work coupling digital botanical images with

scientific explanations/descriptions designed for

the general public (see p. 47).

Glenn Shelton, Humboldt State University. 1st

place, A charismatic salt rush inflorescence, $500

Botany 2012 Student Travel Award.

Sean Gershaneck, University of Hawai’i at

Manoa. 2nd place, ‘Ōhi’a Lehua at Akanikōlea, $250

Botany 2012 Student Travel Award.

Andrew Crowl, University of Florida. 3rd place,

Cocos nucifera (coconut) dispersal in action, $150

Botany 2012 Student Travel Award.

The BSA Graduate Student

Research Award including the

J. S. Karling Award

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

support graduate student research and are made

on the basis of research proposals and letters of

recommendation. Within the award group is the

J. S. Karling Graduate Student Research Award.

This award was instituted by the Society in 1997

with funds derived through a generous gift from

the estate of the eminent mycologist, John Sidney

Karling (1897–1994), and supports and promotes

graduate student research in the botanical sciences.

The 2012 award recipients are:

J. S. Karling Graduate Student

Research Award

Matthew P. Nelsen, University of Chicago.

Advisor: Dr. Richard Ree. “Early, on time or

‘fashionably’ late? The comparative dating of lichen

symbionts.”

41

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

BSA Graduate Student

Research Awards

Guadalupe Borja, Oklahoma State University.

Advisor: Dr. Andrew Doust. “Integrating phylogeny,

morphology, and population genetics: Investigating

species relationships in Paysonia (Brassicaceae).”

Louisa G. Carter, University of Georgia.

Advisor: Dr. Shu-Mei Chang. “Range limits and

conservation in species of a Florida endemic plant

genus, Polygonella.”

Gretel Clarke, University of Vermont. Advisor:

Dr. Alison K. Brody. “Assessing the effects of

pollinators, seed predators, and vertebrate

herbivores on the demography of females and

hermaphrodites in the gynodioecious plant,

Polemonium foliosissimum.”

Julieta Gallego, Museo Paleontológico Egidio

Feruglio. Advisor: Dr. N. R. Cúneo. “Analyses

of diversification rates of Patagonian Paleozoic

and Mesozoic lineages of gymnosperms through

calibration of molecular and morphological

phylogenies.”

Rachel M. Germain, University of Toronto.

Advisor: Dr. Benjamin Gilbert. “Evolution of

coexistence mechanisms in Mediterranean annual

plant communities.”

Rachel A. Hackett, Central Michigan University.

Advisor: Dr. Anna K. Monfils. “Influence of

landscape and local factors on plant communities.”

Kristen Hasenstab-Lehman, Rancho Santa

Ana Botanic Garden and Claremont Graduate

University. Advisor: Dr. Lucinda A. McDade.

“Testing adaptive radiation in the dry tropics:

A phylogenetic approach to biogeography,

inflorescence evolution, and hydraulic traits in the

genus Varronia (Cordiaceae, Boraginales).”

Laura Lagomarsino, Harvard University.

Advisor: Dr. Charles C. Davis. “Phylogeny and the

eolution of vertebrate pollination syndromes in the

Neotropical Lobelioideae, a rapid, recent radiation

in the Tropical Andes.”

Jacob B. Landis, University of Florida. Advisor:

Dr. Pamela S. Soltis. “Corolla length does matter:

Investigating genetic underpinnings of size.”

Vanessa Lopes Rivera, University of Texas at

Austin. Advisor: Dr. Jose L. Panero. “Reconstructing

the spatiotemporal evolutionary patterns of the

Brazilian Cerrado Eupatorieae and Lychnophorinae

(Asteraceae).”

Kristen Sauby, University of Florida. Advisor:

Dr. Robert D. Holt. “Determining the consequences

of herbivory by the invasive South American

cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera:

Pyralidae), to native Opuntia populations in

Florida.”

Brian J. Sidoti, University of Wisconsin-

Madison. Advisor: Dr. Kenneth M. Cameron.

“Molecular phylogenetics and population

genetics of the Tillandsia fasciculata complex

(Bromeliaceae): Biogeographical and evolutionary

implications.”

Sarah Tepler, University of California,

Santa Cruz. Advisor: Dr. Jarmila Pittermann.

“Understanding drivers of variability in the carbon

physiology of the giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera.”

Jinshun Zhong, University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth A. Kellogg. “The evolution

of floral symmetry across the order Lamiales.”

The BSA Undergraduate

Student Research Awards

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research

Awards support undergraduate student research

and are made on the basis of research proposals

and letters of recommendation. The 2012 award

recipients are:

Jenna Annis, Eastern Illinois University.

Advisor: Dr. Janice M. Coons. “Evaluating seed

ecology of federally threatened Pinguicula ionantha

(Godfrey’s butterwort).”

Ian A. Harkreader, Drake University. Advisor:

Dr. Nanci Ross. “Pollination biology and habitat

preference of a rare native lily, Lilium michiganense.”

Hillary Karbowski, Central Michigan University.

Advisor: Dr. Anna K. Monfils. “Local abiotic factors

and plant assemblages: An investigation into prairie

fen biodiversity.”

Caprice Lee, University of California, Davis.

Advisor: Dr. Sharman Diane O’Neill. “Novel

embryological study of Vanilla planifolia using

confocal scanning laser microscopy.”

Tess Nugent, University of Michigan. Advisor:

Dr. Selena Y. Smith. “Investigating potential causes

for variation in δ

13

C discrimination in Ginkgo

biloba.”

Jennifer O’Brien, Eastern Illinois University.

Advisor: Dr. Janice M. Coons. “Enhancing seed

germination and determining the seed bank of the

federally threatened Scutellaria floridana.”

42

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

Bryan Thompson, State University of New

York at Plattsburgh. Advisor: Dr. Chris Martine.

“Hydroponic technology: The future of farming

and its ecological benefits: Growth rate response

and productivity of Ocimum basilicum and super

beefsteak tomato within a soilless environment

compared to a soil environment.”

The BSA Young Botanist

Awards

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual

recognition to outstanding graduating seniors

in the plant sciences and to encourage their

participation in the Botanical Society of America.

The 2012 Certificate of Special Achievement award

recipients are:

Rebbecca Allington, SUNY Plattsburgh.

Advisor: Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Jenna Annis, Eastern Illinois University.

Advisor: Janice M. Coons

Maggie Brown, Miami University. Advisor: Dr.

John Z. Kiss

April Diebold, University of Missouri. Advisor:

Dr. J. Chris Pires

Garrett Dienno, Miami University. Advisor: Dr.

John Z. Kiss

Chloe Drummond, Oberlin College. Advisor:

Dr. Michael J. Moore

Patrick Ellis, Vassar College. Advisor: Dr. Mark

A. Schlessman

Francisco Gomez, Florida Museum of Natural

History. Advisor: Dr. Pam Soltis

Monica Hernandez, University of California-

Los Angeles. Advisor: Dr. Ann Hirsch

Emilie Jordao, Central Michigan University.

Advisor: Dr. Joanne Dannenhoffer

Kelly Matsunaga, Humboldt State University.

Advisor: Dr. A. Mihail Tomescu

Britany Morgan, Rutgers University. Advisor:

Dr. Steven Handel

Jennifer O’Brien, Eastern Illinois University.

Advisor: Dr. Janice M. Coons

Gina Pahlke, Willamette University. Advisor:

Dr. Susan Kephart

Rachel Plumb, Oberlin College. Advisor: Dr.

Michael J. Moore

Audrey Ragsac, University of California.

Advisor: Dr. Paul Fine

Kendalee Richardson, Weber State University.

Advisor: Dr. Barbara Wachocki

Selina Ruzi, Rutgers University. Advisor: Dr.

Steven Handel

Megan Saunders, Hillsdale College. Advisor: Dr.

Ranessa L. Cooper

Jennifer Schmalz, Weber State University.

Advisor: Dr. Barbara Wachocki

Glenn Shelton, Humboldt State University.

Advisor: Dr. A. Mihail Tomescu

Christopher Steenbock, Humboldt State

University. Advisor: Dr. A. Mihail Tomescu

Lauren Stutts, Campbell University. Advisor:

Dr. J. Christopher Havran

Michael Terbush, Ohio University. Advisor: Dr.

Harvey E. Ballard Jr.

Weston Testo, Colgate University. Advisor: Dr.

James E. Watkins Jr.

Betty Unthank, Miami University. Advisor: Dr.

John Z. Kiss

Megan Ward, SUNY Plattsburgh. Advisor: Dr.

Christopher T. Martine

Tim Williams, Ohio University. Advisor: Dr.

Sarah E. Wyatt

Codi Q. Yeager, Cornell University. Advisor: Dr.

Lee B. Kass

Developmental & Structural

Section Student Travel Awards

Xiaofeng Yin, Miami University. Advisor: Dr.

Roger Meicenheimer. Botany 2012 presentation: “A

quantitative analysis of discontinuous phyllotactic

transition in Diphasiastrum digitatum.” Co-author:

Roger Meicenheimer.

Christina Lord, Dalhousie University.

Advisor: Dr. Arunika Gunawardena. Botany 2012

presentation: “Actin microfilaments: Key regulators

of programmed cell death (PCD) in the lace plant.”

Co-authors: Adrian Dauphinee and Arunika

Gunawardena.

Nelson Salinas, New York Botanical Garden.

Botany 2012 presentation: “Uncovering venation

patterns in neotropical blueberries (Vaccinieae:

Ericaceae) and their value for systematics.” Co-

author: Paola Pedraza-Peñalosa.

43

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

Nicholas Miles, University of Florida. Advisor:

Dr. Pamela Soltis. Botany 2012 presentation:

“Virus-induced gene silencing in carnivorous

pitcher plants.”

Co-authors: Douglas Soltis and

Pamela Soltis.

Jacob Landis, University of Florida. Advisor:

Dr. Pamela Soltis. Botany 2012 presentation: “All in

the family: Pollination syndromes and floral traits

in the flowering plant family Polemoniaceae.” Co-

authors: Douglas Soltis and Pamela Soltis.

Genetics Section Student

Travel Awards

Michael McKain, University of Georgia.

Advisor: Dr. Jim Leebens-Mack, for the paper “The

effect of paleopolyploidy on genome evolution

in Agavoideae.” Co-authors: Norman Wickett,

Yeting Zhang, Saravanaraj Ayyampalayam, Richard

McCombie, Mark Chase, Joseph Pires, Claude

dePamphilis, and Jim Leebens-Mack.

Travis Lawrence, CSU Sacramento.

Advisor: Dr. Shannon Datwyler, for the paper

“Testing the hypothesis of allopolyploidy in the

origin of Penstemon azureus (Plantaginaceae).” Co-

author: Shannon Datwyler.

Mycological Section Student

Travel Awards

Wesley Beaulieu, Indiana University.

Advisor: Dr. Keith Clay, for the paper “Cosmopolitan

distribution of ergot alkaloids produced by

Periglandula, clavicipitaceous symbionts of the

Convolvulaceae.” Co-authors: Katy L. Ryan, Daniel

G. Panaccione, Richard E. Miller, and Keith Clay.

Eduardo Campana, Kent State University.

Advisor: Dr. Christopher Blackwood, for the paper

“Fungal communities of northeastern Ohio.”

Carla Harper, University of Kansas.

Advisor: Dr. Thomas N. Taylor, for the paper

“Antarctic wood-decay fungi in glossopteridalean

roots and stems.” Co-authors: Thomas Taylor and

Michael Krings.

Phytochemical Section

Student Travel Award

Rachel Meyer, City University of New York.

Advisor: Dr. Amy Litt. Botany 2012 presentation:

“Molecular and chemical differences among Asian

eggplants analyzed in a framework of their history

of utilization.” Co-authors: Bruce Whitaker and

Amy Litt.

Pteridological Section &

American Fern Society Student

Travel Awards

Amanda Grusz, Duke University. Advisor:

Dr. Kathleen Pryer. Botany 2012 presentation:

“Using next generation sequencing to develop

microsatellite markers in ferns.” Co-authors:

Michael Windham and Kathleen Pryer.

Stacy Jorgensen, University of Vermont.

Advisor: Dr. David Barrington. Botany 2012

presentation: “New insights into the heritage of

Pacific Northwestern polyploids in the genus

Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae).” Co-author: David

Barrington.

Meghan McKeown, University of Vermont.

Advisor: Dr. David Barrington. Botany 2012

presentation: “A molecular phylogeny based

on seven markers supports the inclusion of

the Australian monotypic genus Revwattsia

(Dryopteridaceae) in Dryopteris.” Co-authors:

Michael Sundue and David Barrington.

Weston Testo, Colgate University. Advisor:

Dr. James E. Watkins. Botany 2012 presentation:

“Comparative gametophyte ecology of the

American hart’s-tongue fern and associated fern

taxa: Evidence for recent population declines in

New York State.” Co-author: James E. Watkins.

The BSA PLANTs Grant

Recipients

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual

recognition to outstanding graduating seniors in the

plant sciences and to encourage their participation

in the Botanical Society of America.

Dominique Alvis, University of Maryland-

Baltimore. Dr. Mauricio Bustos

Haydee Borrero, Florida International

University. Dr. Suzanne Koptur

Maria Friedman, Humboldt State University.

Dr. Erik Jules

Erin Fujimoto, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Dr. Tom Ranker

Victoria Hanna, University of California-Irvine.

Dr. Kailen Mooney

Sean Gershaneck, University of Hawaii at

Manoa. Dr. Pattie Dunn

Lauren Gonzalez, University of New Orleans.

Dr. Charles Bell

44

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

Alexandria Igwe, Howard University. Dr. Mary

McKenna

Jamie Minnaert-Grote, George Mason

University. Dr. Andrea Weeks

Rylan Sprague, Black Hills State University. Dr.

Benjamin van Ee

Brittany Stallworth, Howard University. Dr.

Mary McKenna

Dori Thompson, Texas State University-San

Marcos. Dr. Garland Upchurch

Val Yerby, Texas State University-San Marcos.

Dr. Nihal Dharmasiri

BSA Student Activists Visit

Capitol Hill

Marian Chau (PhD candidate, University of Hawaii

at Manoa) is one of the current Student Representatives

on the BSA Board of Directors, and Morgan Gostel (PhD

student, George Mason University) is a BSA student activist

representing the DC area, and recently elected as the next

incoming Student Representative.

We recently attended Congressional Visits

Day, sponsored by the Biological and Ecological

Sciences Coalition (BESC), American Institute

of Biological Sciences (AIBS), and the Ecological

Society of America (ESA). On the first day, we

took part in a public policy training session, and

we visited Congress the next day. The training

session was great, with short informative talks from

Kei Koizumi (White House Office of Science and

Technology Policy), Jane Silverthorne (NSF), and

Julie Palakovich Carr (AIBS) that gave information

on the national budget from different perspectives.

Nadine Lymn and other folks from ESA oriented

us for the Congressional meeting experience, and

then we met with our smaller groups to plan the

next day. Morgan was with other folks from mid-

Atlantic states, and Marian was placed with Florida

(I suppose we were the tropical contingent!).

Marian’s Experience

Our Hawaii/Florida team was led by Liza Lester,

ESA Communications Officer, who facilitated our

day of meetings. One of our Florida constituents

actually didn’t show up, so it was just Liza,

Adam Rosenblatt—a grad student from Florida

International University who does ecology in the

Everglades—and myself. I actually really enjoyed

being in the small group, and the three of us became

friends who will definitely stay in touch.

We visited all of the Hawaii and Florida

senators’ offices, and a few representatives’ offices.

I led meetings with Hawaii’s congressional staff,

and Adam led meetings with Florida’s. As you can

imagine, that made for a full and hectic day of

meetings—we walked back and forth between the

Senate and the House office buildings a lot, walking

past the Capitol at least four times!—but it was

really fun, too. Hawaii’s Congressional members

are all Democrats, so not too surprisingly they

were quite supportive of science, research, and the

President’s proposed budget that would increase

funding for NSF to $7.3 billion (4.8%) in FY 2013.

Beyond that, what was interesting and encouraging

to me was that the legislative assistants I spoke with

were generous with their time and were happy

to talk to me, and to learn about things such as

research at UH Botany, our recently NSF-funded

Consortium of Pacific Herbaria, and rare plant seed

storage at Lyon Arboretum in Hawaii. They seemed

eager to learn more about how NSF directly benefits

our state. I also talked to a couple of them about

PlantingScience, and what an excellent investment

of NSF funding that has been for making strides

in STEM education, along with how NSF funding

has benefited other BSA students. Because Hawaii

Sen. Daniel Inouye is now the Chairman of the

Appropriations Committee, it is great to know that

he is a strong proponent of funding for scientific

research.

Being present for the meetings with Florida

congressional staff was very interesting too. The

Democrats were again supportive of increasing

funds to NSF, but even the Republicans were at

least generally supportive of scientific research and

open to talking to us. Only one was not supportive

of increases (Rep. Cliff Stearns, R-FL), but at least

Marian Chau sitting at the desk of Senator Akaka, one of

her Hawaii Congressmen, after meeting with a staffer

45

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

already planning to visit directly with my congress-

people when they are home for August recess) and

will encourage other BSA students to get involved,

starting with our workshop at Botany 2012.

Morgan Gostel (far right) with other members of the

Mid-Atlantic team visiting Capitol Hill.

Morgan’s Experience

Overall, I had the same sentiments as Marian and

was also quite impressed with how welcoming and

generous congressional staff were with their time.

My group included constituents from Maryland,

Pennsylvania, and Virginia and was led by the ESA

Director of Public Affairs, Nadine Lymn. Our Mid-

Atlantic delegation included graduate students,

a postdoc, and the current president of the ESA,

Steward Pickett. We met with congressional staffers

for both of the state senators from Pennsylvania

and Maryland and one from my home state (Mark

Warner, D-VA). Each of us also had meetings with

our local state representatives, with whom we are

constituents; a couple of folks in my regional group

actually had a chance to speak directly with their

representative! In all cases, the meetings were well

received and there were opportunities to exchange

research anecdotes that related directly to the

central issue: funding science is important!

Some offices were, of course, more receptive

than others, and there seemed to be a universal

concern with uncertainty over budget priorities.

Being an election year, it was suggested that budget

understood the importance of scientific research

and did not want to decrease funds to NSF. He was

honest about his doubts that Congress would even

manage to pass a budget before the new fiscal year,

and thought that we’d be pretty lucky to get one that

keeps funding level, but hey, he’s just being a realist.

The legislative director for Sen. Marco Rubio (R-

FL) was a happy surprise, as we had a very friendly,

entertaining, and productive meeting with her. Not

only was she strongly in support of NSF funding,

she was also generous with her time and even

traded personal stories with us.

The variety of congressional staff we spoke with

was interesting. One was an AAAS Congressional

Fellow and an oceanographer, and it was great

talking to another scientist. Other legislative

assistants specialized in areas such as education,

energy, and financial services, and the legislative

director I mentioned before (for Rubio) was

actually pretty high up in the chain of command—

and you could tell she had a lot more experience.

Also interesting were the differences between the

House and Senate. House offices were smaller and

seemed to be rather hectic and less organized.

At all of these meetings, we were sitting with the

staffer in the office lobby, sometimes with several

other things going on around us. Senate offices

tended to be much larger, labyrinthine even, with

a lot more staff, and we always met in conference

rooms or offices. Although I was disappointed

that my planned meetings with my actual senators

didn’t pan out, we did get to meet with Sen. Daniel

Akaka’s (D-HI) staffer in the senator’s office—and

we got a fun photo op of me sitting at his desk. After

our meetings were done, Liza, Adam, and I went

back to the Capitol to visit the House gallery. By

this time it was after 5 pm, and amusingly we got

to watch a congressman give a passionate speech

to an almost entirely empty House floor—if that’s

not a metaphor for something, I don’t know what

is! After that, Liza and I met up with Morgan

over happy hour to decompress and trade some

stories. An exhausting but productive, educational,

entertaining, and great day.

I would like to thank BSA for sponsoring me

to attend this event! It was just a great experience

overall. Not only did I learn a lot about how

Congress works (and doesn’t!), I also got some great

practice at being a “people person” and interacting

with folks who have some influence on the country’s

purse strings—as well as other science activists. I

will definitely stay involved in public policy (I’m

46

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

issues probably would not be confronted in earnest

until later in the year, closer to November and

December. In most cases we were encouraged not

to let this event be a one-off and to remain involved

in scientific policy issues as they arise, even if it just

means calling in to clarify a point or error made

on a radio show or writing to encourage support

of relevant legislative issues when they are coming

up for a vote. Of course, the simplest way to have

your voice heard is just to vote each November. As

a student myself, I frequently hear fellow students

mention that they either have not updated their

voter registration or in many cases do not vote as

an absentee (yes, we’re usually far from home).

We’ve recently seen how much of an impact young

voters can have and it’s important to stress the value

of your vote and encourage your fellow students to

vote as well!

Overall, the Congressional Visits Day was a great

experience and I was glad to have the opportunity

to represent the BSA! I owe a huge thanks to Marian

for asking me if I’d like to participate and also to

the ESA, BESC, and AIBS for organizing such an

important event. I look forward to staying involved

with AIBS and BSA, and science policy issues.

To conclude, we both strongly encourage

students/postdocs to get more involved in public

policy issues that concern botany and other

biological sciences. A very easy way to start is to

join AIBS’s Action Center online: http://capwiz.

com/aibs/home/. You’ll receive action alerts when

important issues come up, and you can make a

difference simply by writing your congresspeople

through AIBS’s easy interface. If you want to make

a bigger impact, please register for our Botany 2012

Workshop: “Influencing Science Policymakers: A

Workshop for Students and Early Career Scientists”

(WS12, Sunday, July 8, 3:15–5:15 pm). Registration

is free for students and early career scientists,

courtesy of BSA.

Your current BSA Student Reps (Marian and

Megan) also have great news. At the BSA board

meeting in April, we proposed a new BSA Public

Policy Award that will support two students

to attend Congressional Visits Day each year

(including travel and accommodation expenses;

the training/meeting support are provided

free of charge by AIBS). The BSA Board voted

unanimously to establish this new student award

beginning in 2013!

-Marian Chau and Morgan Gostel

Marian Chau with a fellow grad student activist

(the Hawaii-Florida team) visiting Capitol Hill.

47

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

2012 Triarch “Botanical Images”

Student Travel Award Winners

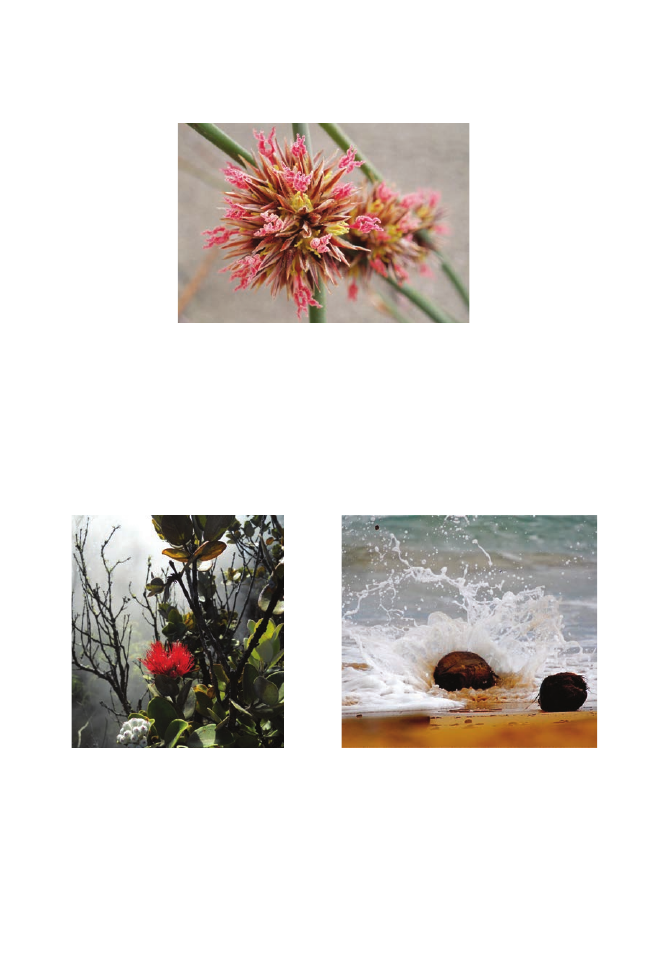

A charismatic salt rush inflorescence

Glenn Shelton, Humboldt State Univeristy

Rushes and other grass-like plants are frequently overlooked amidst a landscape of showy entomophilous

(insect-pollinated) flowers. However, up close their inflorescences can be far from drab. The flowers of this

coastal Juncus species, J. breweri (salt-rush), possess elaborate stigmas bearing vivid pink lobes, looking

very much like ornamented pink corkscrews. Like many other flowering plants, rushes are anemophilous

(wind pollinated). Anemophilous flowers tend to lack showy sepals and petals like those of their insect-

pollinated relatives and instead opt for large exserted anthers and stigmas, and small pollen grains that

are easily carried by the wind. The helical stigma lobes of these salt-rush flowers likely provide optimal

surface area for pollen receipt.

Ōhi'a Lehua at Akanikōlea

Sean Gershaneck,

University of Hawai'i at

Manoa

Ōhi’a Lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha)

is Hawai’i’s most common native tree with a

distribution ranging from coastal forests to the

treeline on some of the world’s tallest mountains

as well as bogs, swamps, and deserts.

Cocos nucifera (coconut)

dispersal in action

Andrew Crowl

University of Florida

Cocos nucifera is the only species in the Cocos

genus (Arecaceae: palm family). It is a primarily

coastal species found throughout the tropics and

subtropics.

48

“The mentors posed great questions and were very

approachable. It seemed like the students were able

to relate to them.”

“Despite being a long time period to commit to one

inquiry, I felt it benefited the students in a number

of ways. First, their ownership and responsibility

was heightened and very evident. Second, they were

thinking and discussing at a level much deeper than

any activity prior to this experience. As a teacher, it

allows me to do true open-ended student-generated

inquiry which is nice.”

Mentor feedback:

“It has provided a benefit in that it counts as

service for me in my job, but more importantly I can

directly help students become better thinkers, which

benefits everyone.”

“I think that learning how to talk to different

levels to students (I am a college professor) helps my

teaching at many levels.”

“It is a lot of fun interacting with students from an

age group I don’t have the chance to spend a lot of time

with. It is a good reminder of where public knowledge

of plant science stands, and a great opportunity for

me to practice explaining key concepts in a simple

and straightforward way.”

As these quotes suggest, there is a special magic

at work when students, teachers, and scientist

mentors engage in collaborations. We are currently

working on major improvements to the website

that will enhance the user experiences. And we

are excited to be working more closely with the 14

partner societies and organizations as the program

plans for the future.

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

PlantingScience

As the spring PlantingScience session ends, almost

12,000 middle and high school science students

and their teachers have collaborated on plant

investigations. Thanks to the Master Plant Science

Team, sponsored by the Botanical Society of

America and American Society of Plant Biologists,

and the >560 scientists who have volunteered as

online mentors since 2005. Students value the

chance to work hands-on with plants and connect

with scientists online. Here are some of the benefits

in the words of a few participants.

Student feedback:

“What I liked most about this experience is learning

about the different traits in a plant and watching the

plant grow.”

“It was fun to be able to interact with an actual

scientist about the experiment and learn new things.

He helped us to point our many things that we would

have never noticed on our own and it was very

helpful.”

“I liked having to figure things out on my own or with

my group and figuring out why things happened and

finding out what would happen if we did this or that.”

“The thing I liked most was being able to talk to a

scientist about what we were doing, and he gave us

helpful suggestions on how to do things. Our scientist

also asked us questions on what we were doing that

helped us keep our minds working.”

Teacher feedback:

“PlantingScience has given me a framework for

open inquiry. Students enjoy working with their

mentors and it gives each group a chance to have

some one-on-one feedback that I don’t always have

time to give them. Students embrace their projects

more than anything else I do in the class and when

they give their final presentations, important topics

such as finding that similar results are often found

between different groups who did similar experiments

to show students how bodies of evidence are built up

by multiple people studying similar topics.”

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Claire

Hemingway, BSA Education Director, at chemingway@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org.

49

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

International Graduate School

Applications Static in the Life

Sciences

Foreign student applications for fall 2012

admissions to U.S. graduate schools saw no growth

in the life sciences. In contrast, applications

increased over last year for all other fields. For

example, education rose by 17%, engineering

increased by 12%, and the arts and humanities

rose by 4%. The top five countries of origin for

international graduate students are China, India,

South Korea, Taiwan, and Canada. The full report

of the 242 institutions by the Council of Graduate

Schools is available online at:

http://www.cgsnet.org/international-graduate-

applications-rise-seventh-consecutive-year-china-

mexico-and-brazil-show-large.

Faculty Leakage by Gender and

the 11-Year Itch

Although male and female faculty are retained

and promoted at similar rates, the good news from

a recent Science article ends there. Less than 50% of

science and engineering faculty hired are retained

over the long term. These departing tenure-track

faculty exit at a median of 10.9 years. The low

retention rates pose significant direct impact costs

and can led to disruption at universities. Expanding

current trends of women hires and retention to

a long-term view, the authors note that gender

equality in science, technology, engineering, and

math (STEM) departments could still be 100 years

away.

Read an article from the Chronicle of Higher

Education on the Science article and a related article

in American Scientist:

http://chronicle.com/article/Gender-Equity-on-

Science/130839/

See a video of Prof. Deborah Kaminski, one of

the study coauthors, talking about the study at:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vIJOvIqHymA

Education Bits and Bobs

Scores up, inclusion down, and

gender preferences in AP courses

Females take the AP Biology test in higher

numbers than males. This is one of the noteworthy

statistics included in the College Board’s 8th annual

report on the Advanced Placement program. The

finding may have implications down the pipeline.

Research shows that students who take AP science

exams are more likely to earn science degrees.

The decade-long trend for increasing numbers of

students taking and succeeding on the AP exams

is also promising. However, of the STEM exams,

scores are lowest for Biology and Environmental

Science. Across all subject areas, underserved

minority and low-income students are significantly

underrepresented in AP classrooms. Access the

report online:

http://apreport.collegeboard.org/report-

downloads

Read a related story: http://blogs.edweek.org/

edweek/curriculum/2012/02/girls_like_biology_

boys_like_p.html

Can Reimagining Community

Colleges Reclaim the American

Dream?

Educating an additional five million students by

2020 is an overall goal of a report released by the

American Association of Community Colleges.

The report is a roadmap for dramatic changes to

community colleges to ensure their role in preparing

students for education and workforce pathways.

Currently, many students arrive at community

colleges unprepared and take at lease one remedial

course. Recommendations in the report suggest

reforms to redesign students’ experiences, reinvent

institutional roles, and reset the system to promote

rigor, transparency, and success.

Access the online report:

http://www.aacc.nche.edu/

AboutCC/21stcenturyreport/index.html

Read a related story: http://blogs.edweek.

org/edweek/college_bound/2012/04/to_move_

community_colleges_ahead.html?cmp=ENL-EU-

NEWS2

50

An Antique Microscope Slide Brings

the Thrill of Discovery into a Con-

temporary Biology Classroom

Riser, Frank. 2012.

American Biology Teacher

74(5): 311-317.

The author purchased a “folk art” handmade

microscope slide from around 1890 from an on-

line antique dealer. The slide contained 90 different

angiosperm seeds, and other propagules, in an

artistic arrangement. Of course there was no key

to the species represented—thus the challenges to

students. How many of these seeds can we identify?

In addition to a beautiful color close-up photo of

the slide, there are 10 more sharply detailed images

of seeds and seed characters. If you don’t subscribe,

it is worth a trip to the library just to see the images!

Exploring Undergraduates’ Under-

standing of Photosynthesis Using

Diagnostic Question Clusters

Parker, J.M., Anderson, C.W., Heidemann,

M., Merrill, J., Merritt, B., Richmond, G., and

M. Urban-Lurain. 2012. CBE Life Sciences

Education 11(1): 47-57.

The authors present an assessment tool that focuses

on common, well-documented misconceptions

about photosynthesis and energy relationships in

plants from the sub-cellular through ecosystem

levels. They demonstrate that properly constructed

groups of multiple choice/true-false questions can

be as effective at identifying student misconceptions

as the more rigorous qualitative techniques of

interviews and open-ended essays. Questions,

and student responses, are summarized in the

appendices.

Backyard Botany: Using GPS Tech-

nology in the Science Classroom

March, K.A. 2012. American Biology Teacher

74(3): 172-177.

I work with Boy Scouts a lot and geocaching has

become the latest thing in teaching orienteering.

The kids love it. The author takes the idea of

geocaching and adapts it to field use for finding and

identifying trees. Adding the GPS makes keying out

the trees much more palatable than the old walk-

around. Why not make it a game? Sometimes we

need all the help we can get to make learning fun!

Editors Choice Reviews

51

Personalia

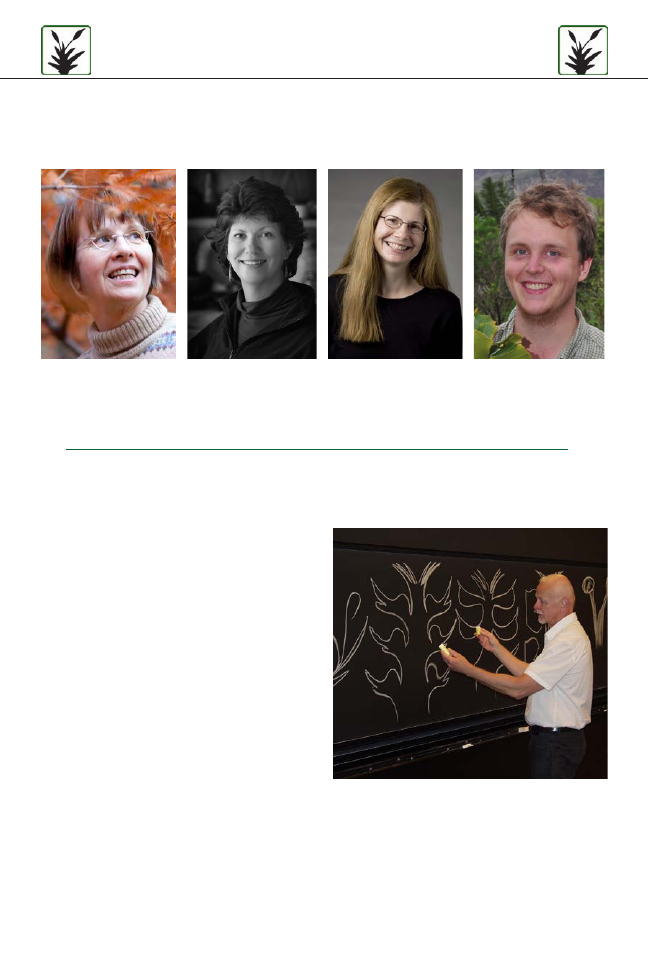

Past-President Karl Niklas

Named One of “Best 300

Professors”

Random House/Princeton Review Books in-

cluded BSA Past-President Karl Niklas as one of the

17 biologists recognized in their recently published

book, The Best 300 Professors. The Princeton Review

teamed with the online site RateMyProfessors to

identify popular professors and combined this with

information from its own surveys and information

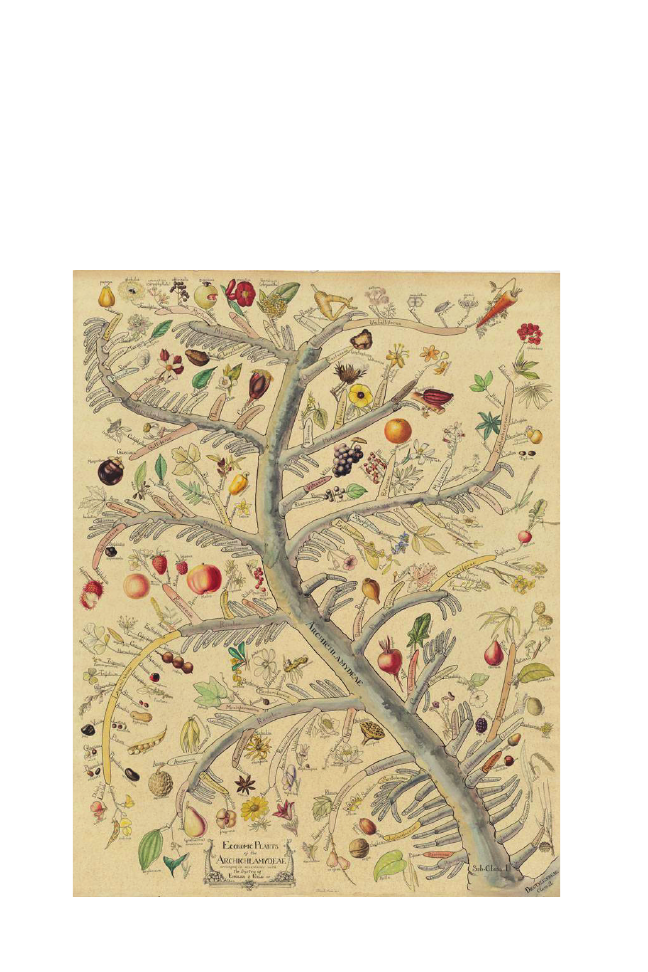

from individual colleges to narrow the list to 300.

For some inspiring comments, check out Karl at

http://www.ratemyprofessors.com. He doesn’t rate

very high on “easiness,” but he certainly inspires his

students (and even gets a “hot” rating!).

BSA Election Results

Congratulations to the newly elected officers of the Botanical Society of America

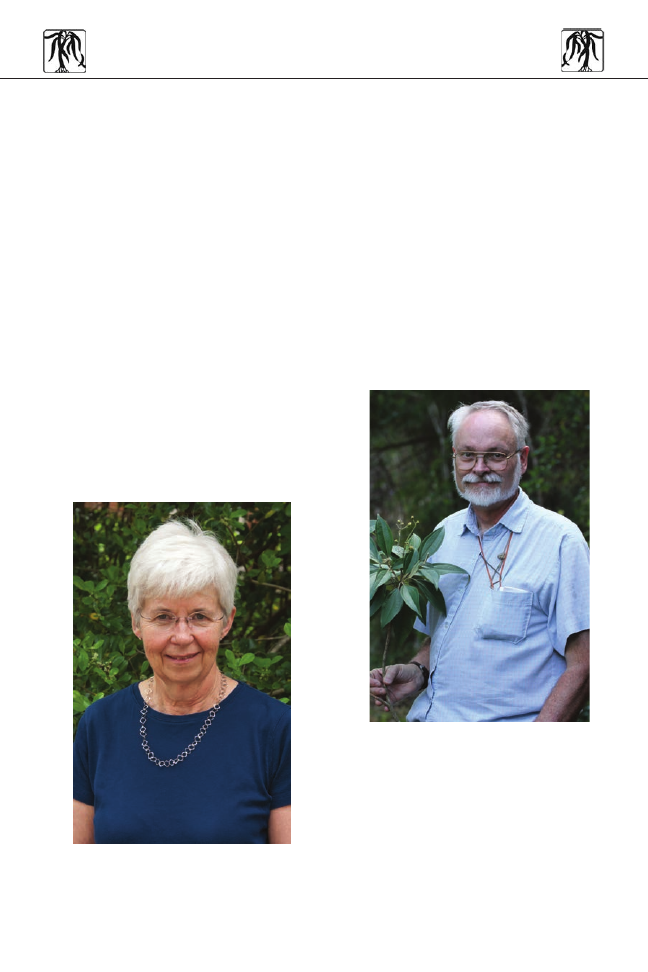

Pam Diggle

President-Elect

Andrea Wolfe

Secretary

Morgan Gostel

Student

Representative

Susan Singer

Director

at Large -

Education

52

Meetings and Conferences

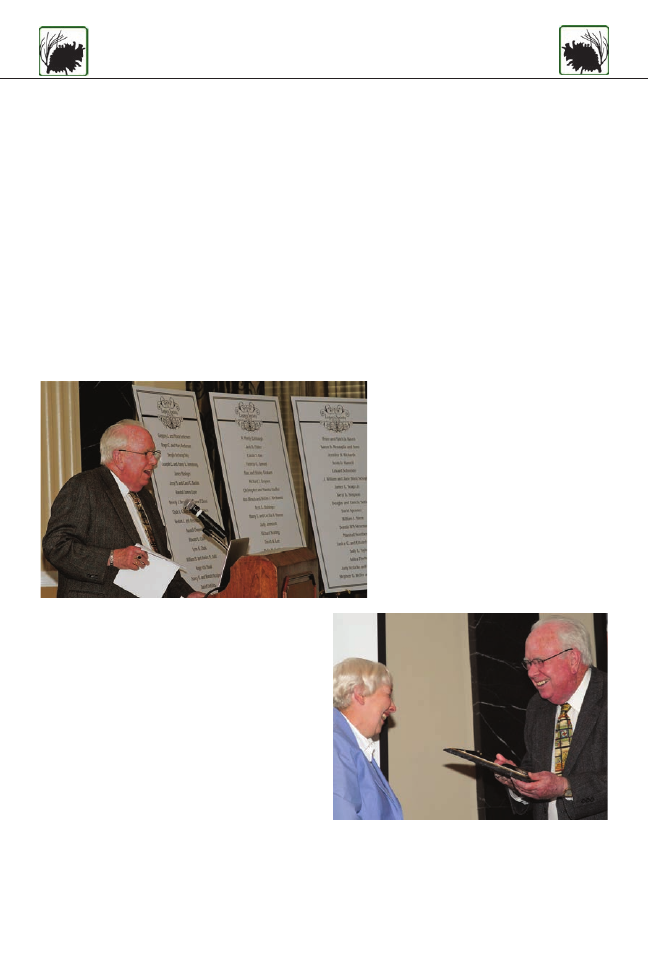

The Legacy Society of the Botanical Society of

America hosted its first regional event in April in

Saint Louis.

Hosted by two of the Legacy Society’s

founders, Drs. Peter and Pat Raven, this very special

evening took place at the historic Chase Park Plaza

Hotel for a night of dinner, drinks, and unique

presentations to honor and recognize the vital

contributions and service of individual BSA

members.

For those of you who may not be familiar with

the BSA’s Legacy Society, the concept for the group

came together during centennial celebrations at

the Botany 2006 Conference in Chico, California.

Senior members of the Society, together with the

Development Committee, determined it was time

to build upon the legacy of giving initiated by

our predecessors. This handful of Legacy Society

founders truly understood the importance of

building and growing an active group to create

a sustainable financial future for the BSA. They

demonstrated their appreciation for the over 100

years of the Society’s history, and all that the Society

has done for its members and the botanical sciences

through planned legacy gifts.

In just over six years, the Legacy Society has

quietly nurtured the vision and has grown its

membership to more than 70 individuals

.

The

generous, individual commitments made by

members of the group will secure the future for

the BSA in its mission to provide members with

research opportunities, conferences, publications,

and awards that help build the careers of young

scientists.

Last year, the Legacy Society felt it was

long overdue that we regularly celebrate the

important individual contributions made

by some of our members and began plans

to sponsor Legacy Society Celebrates events

in regions throughout the country. At this

first event in the Central States region,

historian Dr. Vassiliki

Betty Smocovitis and

current American Journal of Botany editor

Dr. Judy Jernstedt provided enlightening

presentations about the rich history of the

AJB and the BSA.

Saint Louis member

and Assistant Professor of Biology at

Saint Louis University Dr. Allison Miller

The Legacy Society Celebrates

A night that recognized, honored, and applauded

individual service to the

Botanical Society of America

Dr. Judy Jernstedt receives a plaque for her service

as Editor of the American Journal of Botany.

Dr. Peter Raven addresses the BSA Legacy Society.

53

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

demonstrated in her presentation, “Botany in

the Next Generation: Advancing Plant Science

on the Shoulders of Giants,” that the botanical

sciences continue to progress, and that our legacy

is based on a foundation of scientific discovery

passed on from generation to generation. She also

shared how society in general is benefiting from

the dynamic impact and breadth of new genomic

research on the future of our field.

And, since we are approaching the cusp of the

centennial for the American Journal of Botany,

the event was also an opportunity to individually

recognize the service and dedication of our former

and current AJB editors, Drs. Judy Jernstedt, Karl J.

Niklas, Nels R. Lersten, and Theodore Delevoryas.

We thanked them for all that they have contributed

to our Society, and to the development of botanical

sciences.

Finally, the Legacy Society honored its own.

Attending Legacy Society members from the

Central States region were recognized and

applauded for their long-standing commitment,

vision, and financial generosity toward the future of

the BSA. It was truly heartwarming to be a part of

this first Legacy Society Celebrates event.

The BSA has a long tradition of member

commitment and support for everything we

do—from our annual conferences, publications,

education, and outreach programs, to student

awards, lecture funds, and so much more. We

look forward to our next Legacy Society Celebrates

event scheduled to take place on the East Coast,

where additional members will be recognized for

their unique contributions to our Society.

The important foundation of support our

Legacy Society members have provided for the

future of the BSA is truly a testament to their life-

long commitment to our mission, and they carry

forth the tradition of giving that our predecessors

envisioned.

To learn more about becoming a BSA Legacy

Society member, please go to

http://www.botany.

org/legacy/

. We’d be honored to have you participate

in our future!

Dr. Linda Graham

Board Member & Chair, BSA Development Com-

mittee

Dr. Allison Miller shares her presentation, “Botany

in the Next Generation: Advancing Plant Science on

the Shoulders of Giants.”

Dr.Vassiliki

Betty Smocovitis recounts a brief history

of the Botanical Society of America.

54

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

Celebrating 30 Years of

the Flora of the Bahamas:

Conservation and Science

Challenges

An International Symposium

(October 30-31, 2012) at the Bahamas

National Trust and The College of

the Bahamas

The Bahamas National Trust, the College of

the Bahamas, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden,

and Florida International University are putting

together a symposium titled “Celebrating 30 Years

of the Flora of the Bahamas: Conservation and

Science Challenges,” which will take place between

October 30 and 31, 2012. This announcement is to

invite those interested in Bahamian biodiversity to

attend the symposium. We will have a section for

posters and we would like to encourage researchers

and graduate students to present their results using

this avenue. We also have plans to publish the

symposium proceedings in the Caribbean Journal

of Science and, in coordination with the Editor-

in-Chief of this journal (Dr. David L. Ballantine),

the scientific committee will be processing the

submissions (see following submission deadline

details). This announcement and new developments

about the symposium will be posted regularly at

http://www.fairchildgarden/bahamas.

1. Scientific Committee:

Dr. Javier Francisco-Ortega (Associate Professor,

Florida International University and Fairchild

Tropical Botanic Garden)

Dr. Ethan Freid (Botanist, Bahamas National

Trust)

Dr. Brett Jestrow (Herbarium Curator, Fairchild

Tropical Botanic Garden)

Dr. Dion Hepburn (Chair, School of Chemistry,

Environmental & Life Sciences, College of the

Bahamas)

2. Organizing Committee:

Tamica Rahming (Director of Science and Policy,

Bahamas National Trust)

Eric Carey (Executive Director, Bahamas

National Trust)

Dr. Dion Hepburn (Chair, School of Chemistry,

Environmental & Life Sciences, College of the

Bahamas)

Dr. Javier Francisco-Ortega (Associate Professor,

Florida International University and Fairchild

Tropical Botanic Garden)

3. Symposium Background:

Sponsored by Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

and the U.S. National Science Foundation, the latest

comprehensive flora of the Bahama Archipelago

was published in 1982. This project was initiated by

William T. Gillis, but the final work was authored

by Donovan Correll and Helen Correll (illustrated

by Priscilla Fawcett). Since its publication, 30

years ago, this flora has played a major role in

Bahamian education, research, and conservation

because it is still the best available catalogue

for plant biodiversity of this archipelago. The

Bahamas National Trust has a mandate for plant

conservation management in the Commonwealth

of the Bahamas, and in the last 30 years it has been

using this flora as the “manual” for its floristic

activities. However, after recent discussions

between conservation biologists involved in the

symposium, we believe the time has arrived to

evaluate what we know about plant biodiversity in

the Bahamas and what conservation and research

challenges lie ahead. After these discussions we

feel that the 30th anniversary of the publication

of the Flora of the Bahama Archipelago will be a

good moment to organize a symposium to discuss

these issues in an open arena. In the last 30 years

many new research tools have been developed, but

we also have many new environmental challenges.

This is particularly relevant in the Bahamas, where

in the last 30 years: (1) a network of national parks

has been established, and (2) new botanical gardens

with a strong conservation mission have been

recently created or are about to be established.

4. Symposium Agenda:

October 30 (Tuesday):

Morning and afternoon at the College of

the Bahamas (New Library of Oakes Field

Campus, Thompson Boulevard). Oral and poster

presentations (see following list of speakers and

agenda).

October 31 (Wednesday):

A. Morning: Field-trip (tentative depending on

number of interested participants and available

funding) to visit at least one of the New Providence

national parks (Primeval Forest National Park

and/or Harold and Wilson Ponds National Park);

led by Ethan Freid. We are not certain about the

number of slots that we will have available in the

55

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

6. Symposium Fees/Registration,

Accommodation, Abstract, Poster, Proceeding

Guidelines:

6.1. There are no symposium attendance fees.

We are aiming for school teachers to also attend

the symposium; therefore, the event aims to have

a strong community and outreach component. To

register for the symposium, send an e-mail to Javier

Francisco-Ortega at ortegaj@fiu.edu. We would also

appreciate receiving details of: (1) the hotel where

you will stay, (2) if you plan to join the field trip to

the National Park (October 31), (3) if you plan to

attend only the symposium talks at the College of

the Bahamas (October 30), (4) if you plan to attend

only the reception at the Retreat (October 31), and

(4) if you plan to attend the activities offered both

at the College of the Bahamas and at the Bahamas

National Trust (October 30 and 31).

6.2. There are no hotels near the College of the

Bahamas or the Retreat Gardens. However, there

are several hotels along W Bay Street and Bay Street

where you should be able to find accommodation.

We are planning to provide transportation from a

designated point near the hotel area to the College

of the Bahamas and to the Retreat. A passport is

required to travel to the Bahamas, but visa is not

needed for U.S. citizens and legal residents.

Potential hotels are:

British Colonial Hilton - Nassau (Number One

Bay St., Nassau N 7148, Bahamas, Phone: (242)

322-3301)

Towne Hotel (40 George Street, Nassau PO BOX

N-4, Bahamas, Phone: (242) 322-8451)

Nassau Palm Hotel (West Bay Street, Nassau

19055, Bahamas, Phone: (242) 356-0000)

El Greco Hotel (West Bay Street, Nassau,

Bahamas, Phone: (242) 325-1121)

Nassau Junkanoo Resort (West Bay & Nassau

Street, Nassau, 8191, Phone: (242) 322-1515)

There are also several hotels near the airport,

but transportation from this area to Nassau is not

inexpensive.

6.3. Abstracts of posters and lectures from

speakers should be send by e-mail to Javier

Francisco-Ortega at ortegaj@fiu.edu before

September 15, 2012. Each abstract should have a

maximum of 250 words. Although the talks of the

symposium have a focus on the Bahamian flora,

buses; therefore, please indicate in your registration

e-mail if you are interested in joining this field trip.

Participants will be registered for this field trip on a

first-come, first-served basis.

B. Afternoon (starts at 5:00 PM). Reception at

the Retreat Gardens, Headquarters of the Bahamas

National Trust.

B.1. Tour to the garden living collections; led by

Ethan Freid.

B.2. Welcome words by Neil McKinney, President

of Bahamas National Trust.

B.3. Lecture: “Bahamas National Trust Program

to Advance Botanical Education, Research, and

Conservation” by Eric Carey (Executive Director of

the Bahamas National Trust)

5. Oral/Poster Presentations and Speakers

(Symposium, October 30):

1. Dion Hepburn: Welcome words

2. Javier Francisco-Ortega: Introduction to the

symposium

3. Keynote speaker: W. Hardy Eshbaugh, Miami

University (Peter Raven Award recipient, 2008):

“The Flora of the Bahamas, Donovan Correll, and

the Miami University Connection”

4. Ethan Freid: “Plant Endemicity on the Bahama

Archipelago”

5. Lee B. Kass, Cornell University: “Historical

Aspects of Correll & Correll’s flora of the Bahama

Archipelago”

6. Michael Vincent, Miami University:

“Systematics, Taxonomy, and the new Flora of the

Bahamian Archipelago”

7. Brett Jestrow: “From Plant Exploration to

Phylogenetic and Biogeograpical Studies in the

Bahamas”

8. Eric Carey, Director of the Bahamas National

Trust: “Plant Conservation Challenges in the

Bahamas”

9. Carl Lewis, Director of Fairchild Tropical

Botanic Garden: “Establishing Bridges Between

Science, Education, Community Involvement, and

Conservation”

10. Poster Presentations

56

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

we want the symposium to also be an opportunity

for biologists and environmental scientists to show

their results. Therefore, we welcome posters in any

area of environmental biology pertinent to the

Caribbean Islands and South Florida, including

both marine and terrestrial systems. Abstracts will

be posted in the website of the symposium as we

receive them.

6.4. Posters should not be more than 4 feet (121

cm) wide by 4 feet (121 cm) high.

6.5. The deadline to submit manuscripts to

the Caribbean Journal of Science is December 16;

however, we encourage participants to send their

submissions to this journal just around the time

of the symposium. We will have a limited number

of pages for the issue of the Caribbean Journal of

Science devoted to the symposium proceedings.

Manuscripts need to be sent to the Editor-in-Chief

of the journal, Dr. David L. Ballantine, at david.

ballantine@upr.edu. Please indicate in the cover

letter that the manuscript is part of the symposium

proceedings.

MISSOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN

ETHNOBOTANISTS RECEIVE

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

SOCIETY GRANT FOR STUDY AT

CROW CREEK INDIAN

RESERVATION

Project Explores Traditional

Ecological Knowledge of the

Dakota Sioux People

ST. LOUIS, MO—The National Geographic

Society’s Committee for Research and Exploration

has awarded a one-year, $15,150 grant to Dr. Wendy

Applequist, an ethnobotanist at the Missouri

Botanical Garden’s William L. Brown Center,

who will collaborate with fellow ethnobotanist

Karen Walker and Peter Lengkeek, tribal member

of the Crow Creek Indian Reservation, to collect

information about the traditional ecological

knowledge of the Dakota Sioux People living on

the Crow Creek Indian Reservation in central

South Dakota. Native Americans have accumulated

knowledge about their environment for centuries,

developing skills in using plants that grow around

them for food, medicine and shelter. Faced with

an overwhelming potential for this knowledge to

be lost in our modern society, project organizers,

together with tribal members, seek to empower

communities within the reservation to promote

the preservation and use of traditional ecological

knowledge.

Historically, Native Americans have passed

their knowledge from one family to the next

through oral traditions of storytelling, songs and

teaching. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

is a rich part of the cultural heritage of the Dakota

People, who have used the prairie bioregion’s flora

and fauna for food, medicine, dyes, ceremonies

and building materials. In recent times, tribal

members have grown concerned that their valuable

traditional knowledge is being lost as community

elders pass away. Together with former tribal

council member Lengkeek, the Missouri Botanical

Garden designed a research plan to document

the native plant knowledge of their reservation to

ensure this knowledge is continuing to be passed

on for future generations.

The Crow Creek Indian Reservation was

established in 1862, the result of the exile of the

Dakota People formerly living along the lakes

and rivers of Minnesota in the early 1800s. The

400-square-mile area is located in central South

Dakota bordering the Missouri River, and its

terrain includes prairie bioregion, woodlands,

rivers, Missouri Hills and watershed areas. The

reservation is home to over 2,000 people.

Although several ethnobotanical studies have

been conducted with the Sioux Nation in the

past, no such study has ever been conducted on

the Crow Creek Indian Reservation. William L.

Brown Center (WLBC) staff member Karen Walker

and two students from the local tribal high school

are conducting interviews with members of the

reservation to ascertain their native plant use, both

today and in the past. Project organizers predict

that the diversity of species currently used by

the tribe will be reduced due to ongoing cultural

change, but that some plants native to their vicinity

will be newly recorded.

WLBC staff will invite tribal elders who are

considered knowledge holders in the community to

join them in the field, collecting and vouchering all

useful native plants mentioned during interviews

and documenting the traditional process of plant

collection and harvesting management techniques.

Voucher specimens will be housed at the Missouri

Botanical Garden, with duplicates remaining on the

reservation. Staff will also conduct a floristic survey

of the reservation, emphasizing the presence and

57

Plant Science Bulletin 58(2) 2012

explaining and disseminating information about

the diverse and dynamic relationships between

people and plants throughout the world. Today, 153

years after opening, the Missouri Botanical Garden

is a National Historic Landmark and a center for

science, conservation, education and horticultural

display. With scientists working in 35 countries

on six continents around the globe, the Missouri

Botanical Garden has one of the three largest plant

science programs in the world and a mission “to

discover and share knowledge about plants and

their environment in order to preserve and enrich

life.”

distribution of culturally important

plants.

The resulting information will be

amassed in a database and shared with

the tribe at a native plants workshop

this fall. All members of the tribe will

have access to the voucher specimens

and compiled interview data for

purposes of learning and education.

“It is a great honor and privilege to

work with the Dakota Sioux People,”

said Walker. “As we visit with the elders

and community members, recording

TEK, it reinforces the important role

plants have played in traditional diet,

health and religion. The information

that is being shared with us is a

valuable resource to the whole community. It is

also rewarding to see the excitement and energy

from the students involved—there is no better way

to preserve traditional ecological knowledge than

to have the younger generation learning it directly

from their tribal elders.”

With the William L. Brown Center, the Missouri

Botanical Garden is a global leader in discovering,

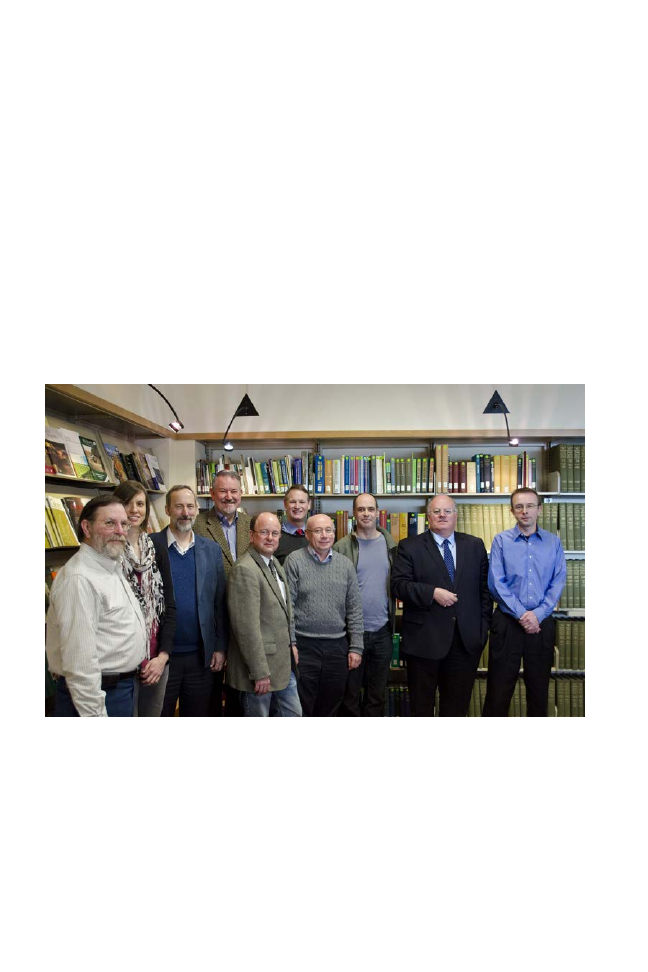

The inaugural American Journal of Botany

special lecture at Botany 2012 will feature Gar

Rothwell (Ohio University), who will present

“Integrating Plant Evolution, Paleontology,

and Molecular Genetics: A Developing

Paradigm.”

Rothwell’s talk will focus on how, within

the developmental framework, evolution can

be interpreted as proceeding by the successive

alteration of ontogeny, which is mediated

via regulatory genetics. Neither genetic

sequences nor experimental manipulations

of development are directly available to the

paleontologist. Nevertheless, by identifying

structural “fingerprints” of developmental

regulatory mechanisms, ontogenetic patterns

can be inferred from the morphology and

anatomy of extinct plant species.

For more information on this talk, go to

www.botanyconference.org.

Special Lecture at Botany 2012

58

task, but with many contributors we can deliver

what is needed.”

“The world’s great botanical gardens are proud to

lead this effort,” said Gregory Long, Chief Executive

Officer and The William C. Steere Sr. President

of The New York Botanical Garden. “Thanks to

advances in our botanical knowledge and in digital

technology, an online World Flora is within our

grasp. It is imperative that we create this resource,

which will help us assess the value of all plant

species to humankind and be effective stewards to

ensure their survival.”

“There are few institutions in the world that have

the capacity to foster this project, and no one of us

could do this alone,” added Dr. Peter Wyse Jackson,

President, Missouri Botanical Garden. “We all

want to see this come to fruition, and the entire

international community will benefit from it. With

the botanical resources and knowledge we each

possess, it was implicit that our institutions would

step forward to collaborate on this project.”

Plants are one of Earth’s greatest resources.

They are sources of food, medicines and materials

with vast economic and cultural importance.

They stabilize ecosystems and form the habitats

that sustain the planet’s animal life. They are also

threatened by climate change, environmental factors

and human interaction. There are an estimated

400,000 species of vascular plants on Earth, with

some 10 percent more yet to be discovered. These

plants, both known and unknown may hold

answers to some of the world’s health, social and

economic problems. A full inventory of plant life

is vital if their full potential is to be realized before

many of these species, and the possibilities they

offer, become extinct.

The critical situation for plants, where at least

100,000 plant species are threatened by extinction

worldwide, has been recognized by the U.N.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). In 2002,

a Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC)