P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Spring 2011 Volume 57 Number 1

Student’s respond to Federal

Policymakers go to page 2

Dr. Elsie Quarterman celebrates

her 100th birthday see page 11

Oldenberg &Van Leeuwenhoek at

the 1994 BSA annual meeting.

Read more on page15

In This Issue..............

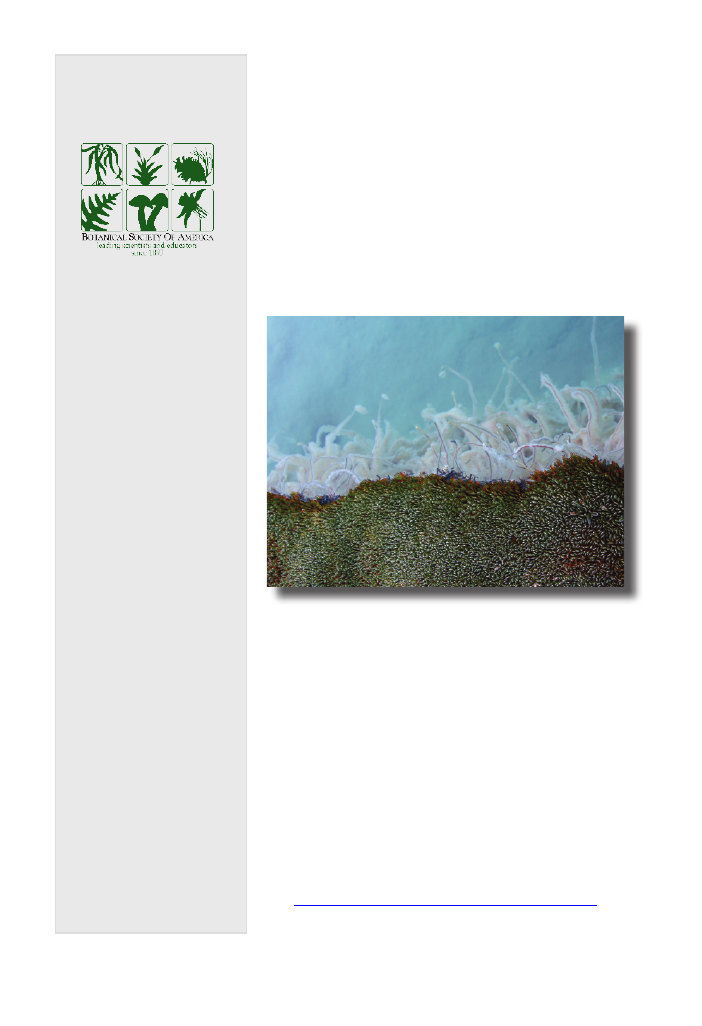

A crystal pond surrounded by cushion plants (Distichia muscoides Nees & Meyen) provides the playground for Nature to play

with shapes and colors beyond the imagination. See Inside back cover for the scientific description.

From the Editor

Spring 2011 Volume 57 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 57

Jenny Archibald

(2011)

Department of Ecology

& Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick

(2012)

Department of Biology &

School of Mathematics &

Statistics

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler

(2013)

Department of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

Department of Biology

State University of New York

at Plattsburgh

Plattsburgh, NY 12901-2681

martinct@plattsburgh.edu

T

he Plant Science Bulletin (PSB) is starting

the year with a new look and high expec-

tations for raising botanical awareness in the

public consciousness. For the past few years

several of us have been representing the Society

on the advisory board of the Botanical Capac-

ity Assessment Project. Through that involve-

ment it became clear that professional botanists

in all sectors, including academe, must become

more proactive in promoting our discipline to

the general public and to policy makers in the

government and federal agencies. In last year’s

issues of PSB you may have noticed letters from

Past-President Holsinger, sent on behalf of the

Society, to key agencies and administrators to

provide input on legislation and spending. In

this issue I’m pleased to recognize the initiative

of our youngest members, whose “An open letter

to federal policymakers from science students”

is now being promoted by AIBS as a vehicle for

all science students to influence policy makers.

Forward the link to your students and encour-

age them to contribute - - then think about ways

you, and the Society, can become more effective

lobbyists for botany.

Also in this issue is a tribute to the late Profes-

sor Larry Crockett, who used history and art to

great effect in teaching botany. He opened my

eyes to the botanical contributions of Antoni van

Leeuwenhoek, which are invariably neglected in

textbooks. I hope you will find this brief review

of the great microscopist’s botanical discoveries

to be enlightening and useful in your teaching.

-Marsh

Carolyn M. Wetzel

Department of Biological

Sciences &Biochemistry

Program

Smith College

Northampton, MA 01063

Tel. 413/585-3687

1

Table of Contents

Society News ............................................................................................. 2

An Open Letter to Federal Policymakers from Science Students ................................2

Open Science Network .................................................................................................3

Science Prize for Inquiry-Based Instruction .................................................................4

Historical Section Announcement for Botany 2011 .....................................................4

BSA Science Education News & Notes ..................................................... 5

Editor’s Choice Reviews ............................................................................ 7

In Memoriam ............................................................................................. 8

Frederick W. Case Jr. (1927-2011) ............................................................................8

William Julian Koch (1925 – 2009) ............................................................................8

Charles H. Uhl (1918 – 2010) ...................................................................................10

Personalia ................................................................................................. 11

Dr. Elsie Quarterman .................................................................................................. 11

Opportunities ............................................................................................ 12

microMORPH Grants .................................................................................................12

2011 Seminars at the Humboldt Institute on the Coast of Maine! ............................12

MSc Degree/Postgraduate Diploma in the Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants .....13

Reports and Reviews ................................................................................ 15

The Botanical Investigations of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek ........................................15

Books Reviewed ...................................................................................... 26

Ecological ...................................................................................................................26

Economic Botany .......................................................................................................29

Historical ....................................................................................................................28

Phycological ...............................................................................................................32

Systematic ...................................................................................................................32

Books Received ....................................................................................... 40

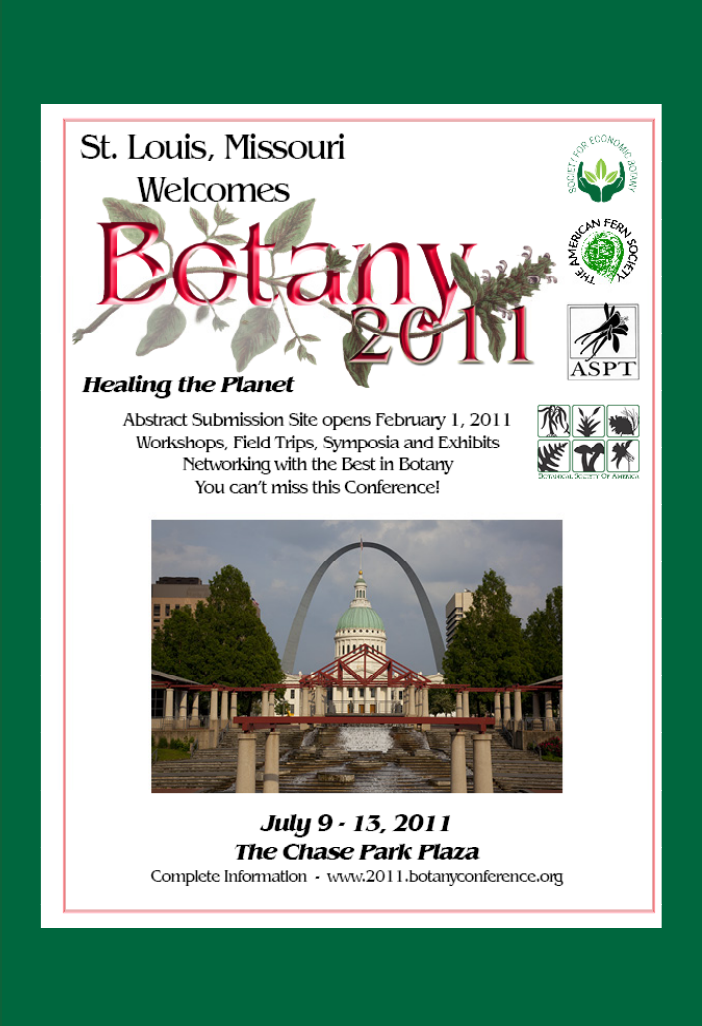

www.botanyconference.org

Register NOW....

2

communicate the change that students want to see:

that by prioritizing science education and research

opportunity, the US can be a leader in innovation.

Statistics on the current state of education in this

country are evidence that this leadership position is

not guaranteed in the future of this country.

I want to acknowledge the leadership and

dedication of the team of students that came

together to take action. You have inspired me

about what is possible to accomplish. You have

also established an example, that future students

can follow, about how students can use the BSA

community to help bring their ideas to fruition.

Please help the number of signatures on the

petition grow by signing and distributing the letter

available through this link:

http://www.aibs.org/public-policy/science_

students_letter.html

Anecdotes:

When one of the faculty at UGA mass e-mailed

the YouCut video, which suggested that citizens re-

review NSF projects as a way to “cut government

waste,” some of our lab members had a brief

discussion that basically amounted to our all shaking

our heads and saying, “somebody oughtta....” After

silence from other quarters, I realized “somebody”

might have to start with me. I approached the

BSA student section with the idea of writing an

open letter and was grateful to find others who

had similar concerns. It’s been enlightening to

work with such a thoughtful group of scientists

who are passionate about science policy, and who

can transform ideas into wording that is concise,

accessible, and politically even-handed.

--from Lindsay Tuominen

In the age of information, it is often difficult for

issues to seem immediate or engaging. But when a

fellow student sent an e-mail out to the BSA student

listserv about the proposed “YouCut” NSF budget

cuts, I felt like we had to do something, not just

as students interested in our own funding but as

members of the larger scientific community. Others

felt similarly, and soon this issue had connected

students from all across the United States, joining

us together in a discussion of what should be done.

Though we are students from various fields and

Society News

On “An open letter to federal

policymakers from science

students”

By Rachel Meyer, student representative of the BSA

I have always been impressed with the energy of

the students in the Botanical Society of America.

Perhaps what makes this society so special is that

the student body is very dedicated to help shape

the BSA, and likewise, the BSA is always looking

for ways to get students involved and to give them

a voice. The result is a community network that

transitions very quickly from idea to product.

The power of this network is beautifully

exemplified by the open letter from students

carrying the message that the US needs not only

to continue, but to strengthen, their investment in

scientific research and education. It started with

one student posting a message to the new student

listserv. It was about the need to respond to the

YouCut program, which targeted the National

Science Foundation’s system of funding research

grants and choice of research projects that deserve

this funding. Several students responded, formed

a group, and wrote a detailed letter on this issue as

a response.

That letter can be viewed at this link:

https://botany.org/BSA_Students-NSF-12162010.pdf

When the BSA office received news of this

student initiative, they immediately were looking

for ways to maximize the potential impact of the

letter. They also wanted to seize the opportunity

for students to learn about how our government

works. When large groups of people come together

with a message to their representatives, they can be

influential. Bill Dahl put me in touch with Robert

Gropp from the American Institute of Biological

Sciences. We immediately began brainstorming

ways the letter could be signed by thousands of

students across the country and sent to potentially

hundreds of people in politics.

Working with AIBS and the original group of

students who wrote the letter, we put together the

petition that is now being circulated among student

members of dozens of scientific societies. We are

acquiring a large number of signatures (in the first

week we had already gained 400). As the number

of signatures grows, we can use the petition to

3

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

backgrounds, we collaborated together to formulate

a nonpartisan response to this attack on the

scientific community and the progress of our nation.

--from Natalie Ma

When I saw the YouCut website, my first

inclination was to jump on Facebook and post my

distaste for the measure. When the opportunity

came to be a part of something larger than a

Facebook rant, I was extremely excited. Working

with a group of young scientists who harbor a

dedication to the future of scientific research

was an amazing experience that I hope to repeat.

Misinformation is a constant phenomenon in the

world today and it makes me feel accomplished

to have been a part of a movement that seeks to

fight misunderstanding. My fellow BSA Student

Action Panel members are amazing and show a

true understanding of issues affecting students,

researchers and our scientific culture. I am very

grateful to them and to BSA for being so supportive

of students seeking to make a difference.

--from Michael McKain

Although I was unable to participate as much in

the earlier part of this process, I was truly impressed

by the way this group of students came together to

take action on such an important issue. Later on I

joined their efforts in editing the letter and getting

it out to students across the country. Using a list of

scientific societies compiled by the BSA student

group, I contacted science policy officers from 21

societies asking them to forward our open letter

to their own student membership. Several of them

replied immediately saying they were forwarding

the message and thanking BSA students for their

leadership and efforts. One society’s president

had already sent the action link to their students

before we even contacted them! Another society

representative thanked us and shared some of their

own activism efforts with us, which we will pass

onto BSA students. It is a great feeling to see our

message being spread across varying disciplines,

encouraging more interactions between us, and to

see that science students across America can come

together in support of political activism that will

benefit our (and future) generations of scientists,

and our country as a whole. I’m honored to be a

part of this terrific group of BSA students who

started it all.

--Marian Chau, student representative of the BSA

Open Science Network

The Open Science Network (OSN) is a National

Science Foundation funded project, coordinated

by the Botanical Research Institute at Texas. OSN

has been leading pioneering work to promote

worldwide collaboration between ethnobiologists

through the continual exchange and enrichment of

educational techniques, materials, and experiences.

This Network champions open educational

resources and uses the latest web technologies to

encourage sharing, generation, and management of

educational tools and curriculum for the traditional

and non-traditional classroom. Ethnobiological

teaching resources have been made openly

available by researchers and educators based at the

University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Frostburg State

University, University of South Carolina, University

of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and University

of Kent among others. Everyone is encouraged to

visit the homepage

1

, to explore the modules and

curriculum posted, as well as contribute resources

of their own.

We will be hosting an educational colloquia

titled Sharing Our Ethnobotany Curriculum:

the Open Science Approach at the 2011 societal

meetings of the Society for Economic Botany

and Botanical Society of America in St. Louis,

Missouri. Presentations will emphasize the

importance of sharing information and resources

among colleagues; demonstrate the need for peer

and student assessments of curricula in order to

maintain fresh and creative ideas in the field; and

touch on how the creation of open technology has

allowed the spread of ideas to the far corners of

the globe. Participants will be introduced to the

web-based portal and instructed how to use and

contribute to its curriculum resources.

OSN has several travel awards available for any

interested educators, students and researchers

that would like to attend and participate in OSN’s

2011 annual meeting. The deadline for these travel

awards is February 22

nd

. For more information

regarding these awards or the Network, please visit

us at our WiserEarth page

2

.

Keri Barfield (kbarfield@brit.org) &

Sofia Vougioukalou (S.A.Vougioukalou@kent.

ac.uk)

Links to websites:

Homepage- www.opensciencenetwork.net

WiserEarth- http://www.wiserearth.org/group/

opensci_ethnobiology

4

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

Science Prize for

Inquiry-Based Instruction

Have you ever actively participated in a science

lab that left a lasting impact on you? Have you ever

taught an interactive science lab and watched as

students lit up with understanding? Science would

like to recognize efforts such as these with the

Science Prize for Inquiry-Based Instruction, which

has been established to encourage innovation and

excellence in education by recognizing outstanding,

inquiry-based science education modules. The

prize is open to any module where students become

invested in exploring questions through activities

that are at least partially of their own design. Rather

than a typical laboratory exercise that begins with

an explanation and results in one correct answer, an

inquiry-based lesson might begin with a scenario

or question and then require students to propose

possible solutions and design some of their own

experiments.

Winners will be selected by the editors of

Science with the assistance of a judging panel

composed of teachers and researchers in the

relevant science fields. Individuals responsible

for the development of the winning resources will

be invited to write a short essay that describes the

resource for publication in Science in 2012. We

encourage all members of the scientific community

to explore their classrooms, departments, colleges,

and universities for nominations in order for the

Science Prize for Inquiry-Based Instruction to truly

represent the best in science education.

To read the accompanying Editorial please visit

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/331/6013/10.

full

For more information and to download

applications please visit http://scim.ag/inquiryprize

Please contact Dr. Melissa McCartney at

mmccartn@aaas.org with any questions.

Melissa McCartney, PhD, Editorial Fellow, Sci-

ence Editorial, 202-285-0300

SCIENCE: www.sciencemag.org

SPORE: www.sciencemag.org/special/spore/

AAAS- Advancing science, Serving society

Historical Section

Announcement for

BOTANY 2011

At Botany 2011 in St. Louis, Missouri this

summer, the BSA Historical Section and co-

sponsoring sections will present a symposium

featuring area botanists. Our decision was based

on the positive feedback we received from similar

symposia organized by the Historical Section

in Chicago, at Botany 2007 and in Rhode Island

for Botany 2010. We invite you to attend our

symposium (see below) and join the exciting field

trip on a behind the scenes look at the extensive

library and herbarium collections at the Missouri

Botanical Garden.

HISTORY OF BOTANY: THE MISSOURI

CONNECTION

Joint symposium with the Historical,

Developmental and Structural, Ecology, Economic

Botany, Paleobotanical Southeastern and

Systematics Sections.

Nuala Caomhanach - “Thomas Nuttall and 19th

Century Botany: The St. Louis Connection”

Michael Long - “George Engelmann’s Fortunate

Connections

Deborah Q. Lewis and Lynn G. Clark - “A.S.

Hitchcock”

Kim Kleinman - “Edgar Anderson, The Missouri

Botanical Garden, & the Rise of Biosystematics”

Betty Smocovitis - “Joseph Ewan and the

Cinchona Missions in Latin America, 1942-1945”

Dennis Stevenson - “William J. Robbins: The

Missouri Years”

Edward Coe - “Lewis J. Stadler: The Nature of

the Gene, and a Clue to DNA”

Lee B. Kass - “Barbara McClintock at the

University of Missouri (1936-1942): The Road to

Transposition”

Following the symposium there will be a field

trip to the Missouri Botanical Garden entitled

“Exploring George Engelmann’s Legacy: The

Missouri Botanical Garden Library and Herbarium”

The Historical Section encourages paper/poster

session contributors. Each year the Emanuel

D. Rudolph award is given for the best student

presentation on an historical subject; this is a cash

award with a complementary banquet ticket.

For additional information please contact the

Symposium Committee:

Marissa C. J. Grant, mgrant39493@lakeland.cc.il.us

or Lee B. Kass, lbk7@cornell.edu

5

PlantingScience

Presentations and Meetings

January 14, 2011. NIBI, The Netherlands

Edith Jonkers, leading the independent Dutch

PlantingScience counterpart, will describe

PlantingScience to Dutch biology teachers.

January 19-22, 2011. Minneapolis, MN:

Association for Science Teacher Education

PlantingScience Co-PI Carol Stuessy and her

graduate students from Texas A&M University

present two sessions “Where the Rubber

Meets the Road in Authentic Science Learning

Contexts: Professional Learning to Classroom

Implementation” and “Applying the Online

Elements of Inquiry Checklist.”

February 3, 2011. Washington, DC: DC

Teachers Night

Katie Engen, ASPB Education Foundation, will

have a hands-on booth to share ASPB activities

and information about the PlantingScience Spring

Online Session and Summer Institute for Teachers.

March 8-9, 2011. Berkeley, CA: Cyberlearning

Tools for STEM Education (CyTSE) Conference

Claire Hemingway will have hands-on

demonstration session at this NSF-sponsored

meeting on K-12 STEM cyberlearning tools.

March 10-13, 2011. San Francisco, CA: NSTA

Conference

Visit us at the booth or attend the March 11 2-3

pm session on “Using Dialogue and Art to Enhance

Science Inquiry and Make Student Thinking

Visible” with PlantingScience teachers Carol

Packard and Allison Landry and botanist/botanical

illustrator Jeanne Debons.

Do you have news or activities you’d like to share

with the PlantingScience community? Please let us

know!

BSA Science Education

News & Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Claire

Hemingway, BSA Education Director, at chemingway@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org.

PlantingScience

BSA-led student research and

science mentoring program

PlantingScience Spring

2011 Session and Program

Happenings.

January is National Mentoring Month http://

www.nationalmentoringmonth.org/ . Celebrate

by committing to mentor middle school or high

school teams as they conduct plant inquiries in the

Spring 2011 Session. It will run 14 Feb. to 15 Apr.

2011). Last fall brought together 177 scientists,

289 student teams, and 30 teachers to collaborate

online. We anticipate another exciting session this

spring. New this spring will be an international

collaboration between Florida and Dutch schools.

Inquiry teaching and learning in school

settings often presents significant challenges, but

PlantingScience teachers are seeking ways to enrich

the experience. Do you wonder what your volunteer

service as an online mentor offers? Participating

teachers share the value of your collaborations with

classrooms in these quotes:

“I am a much better teacher because of this

program...it let my kids enter the classroom as

working lab technicians instead of students ...they

came into class ready to go, prepared to do science.”

“At every opportunity, all involved kept reminding

my students of the process that real science requires.

This helped me to convince my students that they are

really doing science - not just play acting until some

future date.”

“While I sometimes get frustrated with the level of

effort applied by my students I believe that the end

result is worth all the drama. I had several questions

this year that came very close to my goal of valid

scientific inquiry.”

6

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

PlantingScience Summer

Institute for Teachers

June 23-30, 2011. Held at Texas

A&M University, College

Station, TX.

High school and middle school teachers, we

invite you to join botanists Marsh Sundberg

and Larry Griffing and teachers from across the

country to explore plant investigations and inquiry

learning in community. This summer we will focus

on plant physiology and Arabidopsis genetics, and

you’ll have the opportunity to develop a plan to

take any of new or existing inquiry modules to your

classroom. The Institute also offers opportunities

to immerse in the inquiry experience, engage in the

online platform, and share strategies for supporting

team inquiries. Stipends, housing and travel

allowances provided.

Apply online by April 4, 2011. See www.

PlantingScience.org to download a brochure.

http://www.plantingscience.org/institute-

application.html

Science Education

Bits and Bobs

Mixed PISA Results, Scores Improve but High

Achievers Still Scarce in Science — The December

2010 release the most recent data on the Program

for International Student Assessment (PISA)

reiterate the lower than top performance of U.S.

students compared to other nations in reading,

math, and science literacy. Compared to the last

round of PISA data collected in 2006, US students’

science scores for 15-year-olds improved, and the

U.S. average score in science literacy in 2009 is now

not measurably different from the average for other

OECD countries. Countries with higher average

science scores than the US include: Finland, Japan,

Korea, New Zealand, Canada, Estonia, Australia,

the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, the

United Kingdom, and Slovenia. Proficiency in

science literacy is described by PISA according to

levels ranging from 1 to the most advanced of 6.

29% of US students scored at a level 4 in science

proficiency.

PISA Report

http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.

asp?pubid=2011004

8-10 year-old U.K. Students Publish Bee Visual

Perception Research — What can you do with

curiosity about the natural world, access to

science experts, and a few simple rules to a game?

Publish real science for starters. Students in the

Blackawton Primary School, their headteacher, and

a vision researcher from University College London

collaborated on a study of bee vision and behavior.

While the researcher trained the bees in the study,

the students asked the key questions, hypothesized

possible answers, designed experiment features,

analyzed the data and contributed to the manuscript

by drawing the figures and describing their key

findings. This novel publication in “kids speak”

speaks volumes about the power of curiosity and

creativity to fuel science discovery at any age.

See Biology Letters published online 22

December 2010

http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/

early/2010/12/18/rsbl.2010.1056

How much undergraduate learning takes place

on college campuses? — During the first two years

of college, some 45% of students surveyed showed

no significant gains in critical thinking, complex

reasoning, and written communication. Over

four years of college, 36% of students still had no

gains in these critical areas. Academic rigor and

administration priorities play significant roles

according to the Social Science Research Council,

which released the Improving Undergraduate

Learning: Findings and Policy Recommendations

from the College Learning Assessment Longitudinal

study and an associated book on the findings,

Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College

Campuses. Student participation in learning was

not left out of the equation, with study habits

and greater valuation of degree credentials than

knowledge seeking identified as detractors.

7

Editor’s Choice Reviews

Art Instruction in the Botany Lab: A

Collaborative Approach

Baldwin Lyn and Ila Crawford. 2010. Jour-

nal of College Science Teaching 40: 26-31.

“Good observations are often fundamental to good

science, and drawing has long been recognized as a

tool to develop students’ observation skills.” If you

agree with this, the first sentence of the abstract,

you’ll want to read the entire article and consider

establishing a collaboration at your institution.

College Students’ Understanding

of the Carbon Cycle: Contrasting

Principle-based and Informal Rea-

soning

Hartley, Laurel M., Brook J. Wilke, Jonathon

W. Schramm, Charlene D’Avanzo, and

Charles W. Anderson. 2011. BioScience 61:

65-75.

Like the next article, this one is about carbon cycle

misconceptions, but it provides a sound education-

al theory basis to attacking the problem. The tables

will be particularly useful in helping you to identify

misconceptions and how to address that with your

students.

Dust Thou Art Not & unto Dust Thou

Shan’t Return: Common Mistakes in

Teaching Biogeochemical Cycles

O’Connell, Dan. 2010. The American Biol-

ogy Teacher 72: 552-556.

I’ve recommended several articles dealing with

misconceptions about the Carbon Cycle in the past

and here’s another one, treated in a slightly differ-

ent way, that will provide you with some additional

information as you strive to help your students to

develop a more sophisticated understanding of this

concept.

Viewing Plant Systematics through a

Lens of Plant Compensatory Growth

Rea, Roy V. and Hugues B. Massicotte. 2010.

The American Biology Teacher 72:541-544.

Variability and phenotypic plasticity in nature are

difficult concepts for all students, but especially for

new students beginning their observations in na-

ture. What we seldom think about in our teaching

is now the phenomenon of compensatory growth

can be used to illustrate these two difficult con-

cepts. The authors condense multiple years worth

of data and experience to demonstrate the extreme

range of morphology associated with compensa-

tory growth.

“In the biblical account in Genesis of the Noachian Flood, only the animals were taken two by two

onto the Ark. I well remember that I was about twelve years old when the subject came up in Sunday

School, and I wondered out loud what became of the all the plants, most of which could not have

survived underwater. You know how literal-minded young boys can be. I think it was about this time

that the teacher sent a note to my parents, suggesting that I might better spend my Sunday mornings

elsewhere than in Sunday School.”

-Neil A. Harriman, Biology Department, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Oshkosh, Wisconsin 54901

Congratulations to

PlantingScience Teacher

Gwen Foote

Nautilus Middle School

Teacher of the Year!

8

In Memoriam

Pre-deceased by two brothers-in-law, Andrew Cota

and Carl Burckhardt and a niece, Debbie Kress.

A special thank you to his caregiver, Hazel Irvin,

for her assistance during his nearly two years of

declining health.

Those planning an expression of sympathy may

wish to consider the Nature Conservancy of

Alabama, Roberta Case-Pine Hill

Reserve, the Michigan Nature Association, the

Children’s Zoo at Celebration Square, or the charity

of their choice. www.casefuneralhome.com

-Carolyn M. Wetzel, Smith College, Northampton,

MA 01063

Frederick W. Case Jr. 1927-2011

Well known teacher and botanist passed away

Wednesday, January 12, 2011. Age 83 years. The

son of the late Julia Blanche (Coash) and Frederick

W. Case Sr. was born February 16, 1927 in Saginaw,

Michigan. He married Roberta Elizabeth (Boots)

Burckhardt, February 14, 1953. She passed away

June 8, 1998. He was a graduate of Arthur Hill High

School and received his

Bachelor of Science and Master’s in Education

from the University of Michigan. He served with

the U.S. Army during WWII. He returned to

Arthur Hill High where he taught biology and

natural science until his retirement. He was named

their Honor Alumnus in 1978. He was named the

Outstanding Biology Teacher in Michigan in 1971

and Outstanding Science Teacher in 1987. Fred

and Roberta authored three books and authored

or co-authored many articles for magazines

and scientific publications about native orchids,

trilliums, insectivorous plants, wildflowers and

gardening. He received numerous awards and

recognition for his achievements in botany and

lectured extensively. He had been associated with

Cranbrook Institute of Science, The University of

Michigan Matthaei Botanical Gardens, Longwood

Gardens, The Michigan Dept. of Natural Resources

Committee on Endangered and Threatened Plants,

the Michigan Botanical Club, North American

Rock Garden Society, the Saginaw Valley Audubon

Society, Saginaw Valley Orchid Society, The Nature

Conservancy, Michigan Nature Association, and

many other horticultural groups. He enjoyed opera,

theatre, reading, traveling, fine dining and Ketchup.

Surviving are a son and daughter-in-law, David

B. and Sheri Leaman Case; three granddaughters,

Rebecca Case Myers and her husband Chris Myers;

Emily Case and her fiancée, David Krueger, Caitlyn

Case; a brother, a sister and two sisters-in-law,

Win L. and Mary Case; Nancy Cota and Patricia

Burckhardt; nine nieces, Julie Swieczkowski,

Mary Lou Case, Susan Case, Kathy Case, Caroline

Orsini, Amy Case, Jennifer Ashby, Amy Busch,

Lisa Bulmer, two nephews, Stephen Cota, Bob

Burckhardt; his lifelong friend, George L. Burrows

IV; several grand nieces, grand nephews, cousins,

other relatives, many dear and loyal friends. He was

William Julian Koch

(1925 – 2009)

William Julian Koch, age 85, retired Professor

of Botany at the University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill, died 17 July 2009 at his home in

Glendale, AZ, after a brief illness.

William was the fourth of four sons of Frederick

Henry Koch, a pioneer of folk drama in the United

States and the founder of Playmakers Theatre at

UNC, and Loretta Regina Hanigan, a housewife.

A native Chapel Hill, William attended the local

public schools. At UNC he earned three degrees in

botany: B.A. (1947), M.A. (1950), and Ph.D. (1956).

Interrupting his academic studies, he served in the

United States Navy (1943-1946).

9

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

Koch conducted his graduate research in mycology

under the guidance of world renowned mycologist

John N. Couch who inspired William’s scientific

investigations. While a graduate student, he was an

assistant and instructor, both in botany. His master’s

thesis concerned “A study of the motile cells of

Vaucheria,” and his dissertation dealt with “Studies

in the Chytridiales, with special reference to the

structure, movement and systematic significance of

the swimming reproductive cell.” After earning his

doctorate, he joined the faculty in the Department

of Botany at UNC, advancing in the academic ranks

to professor. His early research concerned a group

of water molds, chytrids, on which he published

a series of papers in scientific journals. When he

was asked to assume a heavy teaching load, he

shifted his focus from fungi to humans, especially

undergraduates.

His lively and inspiring classes were always

aimed at stimulating students’ innate curiosity for

knowledge. When teaching a class about edible

plants, William would bring samples for tasting,

and he was known for waking up students by

pouring dried leaves over them. Many of his classes

started with music appropriate to the theme of

the lecture: Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” played

at the beginning of the class in which changes

of trees during the year took place; and the song

“John Barleycorn,” prefaced the class in which

fermentation, including the brewing of beer, took

place. His other primary courses were introductory

botany, plant diversity, introductory mycology, and

advanced mycology. He wrote several textbooks

and laboratory manuals to accompany his courses,

which he designed to arouse an interest in students

and to closely follow his philosophy of teaching (a

humanistic approach).

William’s innovative teaching, genuine enthusiasm,

and engaging personality earned him respect with

students who twice honored him as a featured

faculty member in the school’s yearbook, Yackety

Yack, and celebrated a “Willie Koch Day” on the

UNC campus in 1975. Researchers acknowledged

his role as a scientist through such tributes as

naming a genus of fungus, Kochiomyces, for him in 1980.

William held memberships in a number of

professional associations. He held offices in several

of them, including the Botanical Society of America

(Chairman, Microbiology Section, 1963-1964;

Education Committee, 1978-1980), Elisha Mitchell

Scientific Society (Vice-president, 1960 and 1974;

Recording Secretary, 1961-1967), and Mycological

Society of America (Committee on Research

Grants and Publications). In honorary societies

he was elected to Sigma Xi and held several offices

in its UNC chapter: Vice-president, 1966-1967;

Executive Committee; Nominating Committee,

1976; and Membership Committee, 1975-1978.

In the summer of 1986, William retired to Pembroke

Pines, FL, along with his wife, Dott. He worked

there with handicapped children, and as a movie

actor and model. Subsequently, they relocated to

Glendale, AZ. He then pursued the visual arts and

created computer images of the natural world. He

also published a book and a separate CD (Plant

Close-ups: Designs, 2007) that featured 82 color

photographs accompanied by personal comments.

Interested in the state of the country, he and his wife

volunteered for one year at the Arizona governor’s

office to become better acquainted with societal

problems and possible solutions. In his retirement

settings, the local vegetation captivated William’s

curiosity, just as he had captivated so many students

at the University of North Carolina.

His wife Dorothy “Dott” (Clarke) Koch of Roseville,

CA, survived William at the time of his death, but

she died in 2010. Current survivors include three

daughters, Patricia Margolis of Redondo Beach,

CA, Jean Austin of Jonesborough, TN, and Deb

Plylar of Phoenix, AZ; one son, David “DK” Koch

of Lincoln, CA; ten grandchildren; and three great

grandchildren.

William was cremated, and his ashes have not been spread.

A List of the Graduate Students of William J. Koch

and Their Theses.

• Bernstein, Linda Beryl. 1966. A biosystematic

study of eight isolates of Rhizophlyctis rosea

with emphasis on zoospore variability. M.A.

• Bostick, Linda Roane. 1966. Studies of the

morphology and cytology of Chytriomyces

hyalinus Karling. M.A.

• Clausz, John C. 1965. Some factors affecting

germination of oospores of Achlya hypogyna.

M.A.

• McNitt, Rand Edwin. 1973. Light and electron

microscopy of Phlycochytrium irregulare

Koch. Ph.D. (co-advisor Lindsay S. Olive)

• Powell, Martha J. 1974. Developmental studies

of the chytrid Entophlyctis variabile sp.n. : A

light and electron microscopic investigation. Ph.D.

• Register, Thomas Eugene. 1959. Morphological

variation in a new species of Phlyctochytrium.

M.A.

• Senior, Laura B. 1981. Study of the mycorrhizal

organs of Tipularia discolor, the crippled crane

fly orchid. M.S.

10

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

• Tingle, Constance L. 1972. Some physiological

aspects of oogonia formation in Saprolegnia

diclina. M.A.

-Prepared by William R. Burk, friend and fellow

mycologist.

Charles H. Uhl (1918 – 2010)

Charles H. Uhl, professor emeritus of Plant Biology,

died Aug. 29, 2010, in Jefferson, GA. He was 92.

Born May 28, 1918, in Schenectady, NY, Charlie

moved to Georgia at the age of nine. He earned

his B.A. (1939) and M.A. (1941) from Emory

University, and his Ph.D. from Cornell in 1947.

As for many of his generation, his education was

disrupted by World War II. He served in the U.S.

Navy from 1942-1946 first as an ensign, then as an

executive officer and Lieutenant. He was one of

three officers on a standard landing craft, none of

whom had any marine experience other than the

few months training provided by a wartime navy.

Nonetheless, under orders, he and his crew were

able to successfully guide their small lumbering

boat, without escort and continuously out of sight

of land, some 5000 miles across the Pacific to tiny

Bora Bora using only a sextant (no GPS in those

days!). He and his crew went on to participate in

combat operations in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater in

New Guinea, the Philippines, and Borneo. Charlie

wrote a history of his experiences in the book USS

LCI volume II. After the war, Dr. Uhl finished his

degree and joined the faculty at Cornell in 1947. For

many years Charlie was recognized as the expert on

cytogenetics of the stonecrop family (Crassulaceae)

and published over 80 papers in the field between

1943 and 2004. He created and documented over

1500 specific and generic hybrids in the family.

He holds the record for the highest number of

chromosomes ever counted in an angiosperm, n

= 320 (or a diploid number of 640 chromosomes),

for Sedum suaveolens. Although best known for

his work on hybridization and polyploidy, he had

wide-ranging interests and applied his findings

to taxonomic questions such as the delimitation

of species and genera as well as the phylogenetic

relationships among them. He was also fascinated

with biogeographic questions and published his

observations on the effect of the San Andreas Fault

on speciation in stonecrops. His work is still having

an impact on young researchers as demonstrated by

a recent paper in the American Journal of Botany

that was dedicated to Dr. Uhl.

His family fondly remembers many field trips to the

western U.S. and Mexico to collect succulents for

his research. Over the years, he contributed several

thousand plant specimens to the L. H. Bailey

Hortorium, both from these field trips and from his

laboratory experiments. In 1985 he was elected an

honorary fellow of the Cactus and Succulent Society

for exceptional achievement in scholarship about

succulent plants. In addition to his research, Charlie

is remembered by many as an excellent teacher of

Cytology, Cytogenetics, and Microtechnique. His

labs were well known for having a superb collection

of cytological preparations, and for his enthusiastic

participation. He chaired the graduate degree

committees of a number of students in cytology

and served on the committees of many others in

the fields of both plant biology and plant breeding.

He was also famous for asking probing questions

at departmental seminars where his breadth of

knowledge was apparent to all.

Among Dr. Uhl’s outside interests was stamp

collecting and he was a longtime member of the

Ithaca Stamp Club and American Philatelic Society.

No one in plant biology threw away envelopes from

afar without removing the stamp and handing it off

to Charlie. Charlie had the opportunity as a child

to see the Cyclorama, a 42-foot high cylindrical oil

painting depicting the Civil War Battle of Atlanta,

which at that time was narrated by some of the last

living confederate soldiers. This experience stoked

a life long interest in the civil war.

Charlie is survived by his wife of 65 years, Natalie

Whitford Uhl, also a Cornell emeritus professor;

his four children Natalie Jean of Las Vegas, New

Mexico; Mary of York, England; Charles Jr. of

Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and Elizabeth of Athens,

Georgia; and three grandchildren, Toby, Hugh, and

Amy .

-Melissa A Luckow

11

Personalia

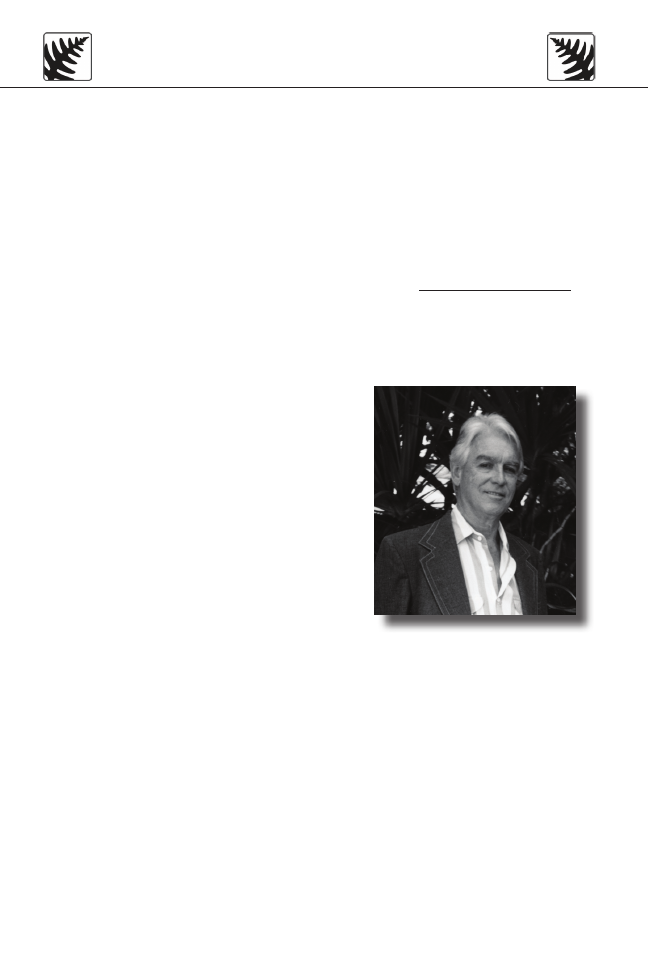

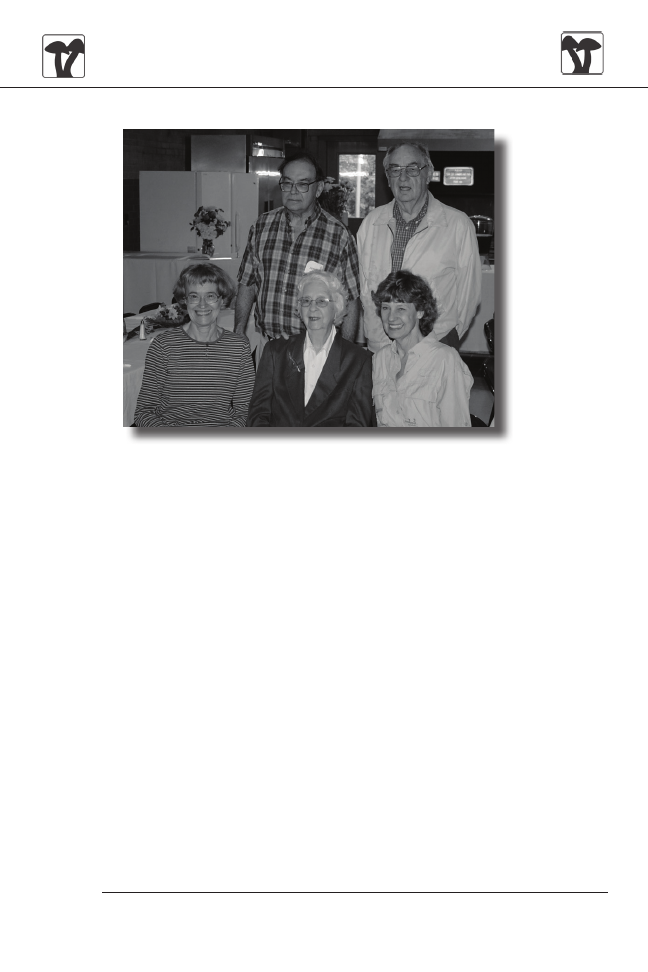

Photo Caption: Left to right: Front row, Carol Baskin, Elsie Quarterman, Gail Baker;

back row , Jerry Baskin, Tom Hemmerly.

Dr. Elsie Quarterman celebrated her 100th

birthday on November 28, 2010. She grew up in

southern Georgia and graduated from what is now

Valdosta State University. While teaching high

school in Georgia during the 1930’s she attended

Duke University in the summers, completing her

master’s degree in plant ecology under Henry J.

Oosting. In 1943 she took a temporary position at

Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN), becoming

one of the first female faculty members. Her

position became permanent and she stayed for 33

years, retiring in 1976. Her Ph. D. dissertation titled

“Ecology of the Cedar Glades of Middle Tennessee”

was completed under Oosting’s direction in 1950.

She met Catherine Keever at Duke in the 1930’s

and they began a life-long friendship and research

collaboration. Dr. Keever, a specialist in old field

succession, taught at what is now Millersville State

University in Pennsylvania. Their most important

joint work—completed after several hot summers

of field work—resulted in a 1962 Ecological

Monographs paper titled “Southern mixed

hardwood forest: climax in the southeastern Coastal

Plain, U. S. A.” In addition to cedar glade ecology,

Dr. Quarterman’s 30-plus publications include

papers on a wide variety of topics, from bryophytes

to forest succession to seed germination.

Always a conservationist, she became more active

after retirement and has received numerous awards

for her efforts to preserve and protect unique and

endangered habitats in Tennessee. Among these are

the Oak Leaf Award from the Tennessee Chapter of

the Nature Conservancy, a Lifetime Environmental

and Conservation Achievement Award from

the Tennessee Department of Environmental

Conservation and the Sol Feinstein Environmental

Award from the College of Environmental Science

and Forestry of the State University of New York.

Nearly all of her graduate students did ecological

research on cedar glade plants. Among her graduate

students are Stewart Ware, Professor Emeritus of the

College of William and Mary, Thomas Hemmerly,

Professor Emeritus of Middle Tennessee State

University, Douglas Waits, Professor Emeritus

of Birmingham-Southern College, Gail Baker of

Northwest Florida State College, and internationally

known seed germination ecologists Carol Baskin

and Jerry Baskin of the University of Kentucky.

- Gail S. Baker, Ph. D.

Dr. Elsie Quarterman

12

microMORPH Grants

microMORPH is pleased to announce a funding

opportunity for undergraduates ($5,000), graduates

students, postdoctorals, and assistant professors

($3,500) in plant development or plant evolution.

These grants are available to support cross-

disciplinary visits between labs or institutions for a

period of a few weeks to an entire semester. We are

particularly interested in proposals that will add a

developmental perspective to a study of evolution

of populations or closely related species. We are

also interested in developmental studies that will

incorporate the evolution of populations or closely

related species. The deadline for proposals is March

1st, 2011. More information about the training

grants and the application process may be found on

the microMORPH website:

http://www.colorado.edu/eeb/microMORPH/

grantsandfunding.html

To be eligible for microMORPH training grants,

applicants must fill at least one of the following

criteria: 1) be a U.S. citizen, or 2) be affiliated with

(enrolled in a degree granting program or employed

by) a U.S. college, university, or institution, or 3)

propose to train in and be hosted by a lab at a U.S.

college, university, or institution.

These internships are supported by a five-year

grant from the National Science Foundation

entitled microMORPH: Molecular and Organismic

Research in Plant History. This grant is funded

through the Research Coordination Network

Program at NSF. The overarching goal of the

microMORPH RCN is to study speciation and the

diversification of plants by linking genes through

development to morphology, and ultimately to

adaptation and fitness, within the dynamic context

of natural populations and closely related species.

If you would prefer not to receive any more emails

from me about the microMORPH RCN, please

email me back with the word “NO” in the subject

line and I will remove you from the mailing list. I

will use this list for occasional updates on funding

opportunities through the microMORPH RCN,

and yearly workshops hosted by microMORPH.

Sincerely,

Pamela K. Diggle (Pamela.diggle@colorado.edu)

Ned Friedman (ned@colorado.edu)

Opportunities

2011 Seminars on at the

Humboldt Institute on the

coast of Maine!

May 22 - 28

Lichens and Lichen Ecology.

David Richardson and Mark Seaward.

May 29 - Jun 4 Crustose Lichens: Identification

Using Morphology, Anatomy, and

Simple Chemistry.

Irwin M. Brodo.

Jun 5 - 11

Bryophytes and Bryophyte Ecology

Nancy G. Slack.

Jun 12 - 18

The Lichen Genera Rhizocarpon,

Fuscidea, Porpidia, and Other

Lecideoid Lichens.

Alan Fryday.

Jun 26 - July 2 Applied Field Identification of Sedges

and Rushes.

Andrew L. Hipp.

Jun 26 - July 2 Aquatic Flowering Plants.

C. Barre Hellquist.

Jul 3 - 9

The Genus Carex: Advanced

Taxonomy and Ecology.

Anton A. Reznicek.

Jul 3 - 9

Botanical Latin for Application and

Enjoyment. Steven R. Hill.

Jul 24 - 30

Botanical Illustration: Sketching and

Painting Wildflowers in Their

Natural Environment.

Angela Mirro.

Jul 31 - Aug 6 Flora of Maine Coastal Habitats and

Islands.

Glen H. Mittelhauser.

Aug 14 - 20

Applied Foundations in Vascular

Plant Morphology.

Susan Pell.

Aug 21 - 27

Taxonomy and Biology of Ferns and

Lycophytes, with Guest Lectures on

Isoetes.

Robbin C. Moran and W. Carl Taylor.

Aug 21 - 27

The Genus Bryum and Bryaceae:

Systematics and Biogeography of

North American Species.

John R. Spence.

13

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

http://www.eaglehill.us/programs/nhs/nhs-

calendar.shtml

Descriptions of seminars may be found at

http://www.eaglehill.us/programs/nhs/nhs-

calendar.shtml

Information on lodging options, meals, and costs

may be found at

http://www.eaglehill.us/programs/general/

application-info.shtml

There is an online application form at

http://www.eaglehill.us/programs/general/

application-web.shtml

Syllabi are available for these and many other fine

natural history training seminars on diverse topics.

For more information, please contact :

Humboldt Institute

PO Box9

Steuben, ME 04680-0009.

207-546-2821. Fax 207-546-3042

E-mail - mailto:office@eaglehill.us

Online general information may be found at

http://www.eaglehill.us

NATURAL HISTORY SEMINARS

In support of field biologists, modern field

naturalists, and students of the natural history

sciences, Eagle Hill offers specialty seminars and

workshops at different ecological scales for those

who are interested in understanding, addressing,

and solving complex ecological questions. Seminars

topics range from watershed level subjects, and

subjects in classical ecology, to highly specialized

seminars in advanced biology, taxonomy, and

ecological restoration. Eagle Hill has long been

recognized as offering hard-to-find seminars and

workshops which provide important opportunities

for training and meeting others who are likewise

dedicated to the study of the natural history

sciences.

Eagle Hill field seminars are of special interest

because they focus on the natural history of one

of North America’s most spectacular and pristine

natural areas, the coast of eastern Maine from

Acadia National Park to Petit Manan National

Wildlife Refuge and beyond. Most seminars

combine field studies with follow-up lab studies and

a review of the literature. Additional information

is provided in lectures, slide presentations, and

discussions. Seminars are primarily taught for

people who already have a reasonable background

in a seminar program or in related subjects, or

who are keenly interested in learning about a

new subject. Prior discussions of personal study

objectives are welcome.

MSc Degree/Postgraduate

Diploma in the Biodiversity

and Taxonomy of Plants

Royal Botanic Gardens

Edinburgh/ University of

Edinburgh

Programme Philosophy

The MSc in Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants

was established by the University of Edinburgh and

the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) to

address the growing worldwide demand for trained

plant taxonomists and whole-plant scientists.

A detailed knowledge of plants and habitats is

fundamental to their effective conservation. To

communicate such knowledge accurately and

effectively, training is required in plant taxonomy

– the discipline devoted to plant diversity and

evolution, relationships, and nomenclature. The

MSc is perfect for those wishing to develop a career

in many areas of plant science:

• Survey and conservation work in threatened

ecosystems

• Assessment of plant resources and genetic

diversity

• Taxonomic research

• Management of institutes and curation of

collections

• A stepping stone to PhD research and

academic careers

Edinburgh is a unique place to study plant

taxonomy and diversity. The programme and

students benefit widely from a close partnership

between RBGE and the University of Edinburgh

(UoE). RBGE has one of the world’s best living

collections (15,000 species across our four specialist

gardens – 5% of world species), an herbarium of

three million specimens and one of the UK’s most

comprehensive botanical libraries. The School of

Biological Sciences at UoE is a centre of excellence

for research in Plant Sciences and Evolutionary

Biology. Recognised experts from RBGE, UoE, and

from different institutions in the UK deliver lectures

across the whole spectrum of plant diversity. Most

course work is based at RBGE, close to major

collections of plants, but students have full access

to the extensive learning facilities of the university.

14

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

Entry Requirements

Applicants should ideally hold a university

degree, or its equivalent, in a biological,

horticultural, or environmental science, and above

all have a genuine interest in plants. Relevant work

experience is desirable but not required. Evidence

of proficiency in English must be provided if this is

not an applicant’s first language.

Funding

The University of Edinburgh provides a limited

number of studentships. Other international

funding bodies have supported overseas students

in the past. More information can be obtained in

the course handbook.

Further Information

For further details on the programme, including

a course handbook please visit the RBGE website:

http://www.rbge.org.uk/msctaxonomy

You can also contact the Course director

or Education Department at RBGE, or the

Postgraduate Secretary of the University of

Edinburgh:

MSc course Director

Dr Louis Ronse De Craene

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

Tel +44 (0)131 248 2804

Email: l.ronsedecraene@rbge.ac.uk

Postgraduate Secretary

The University of Edinburgh

School of Biological Sciences, Darwin Building

The King’s Buildings, Edinburgh EH9 3JR, UK

Tel +44 (0)131 650 7366

Email: icmbpg@ed.ac.uk

To apply online, please go to:

http://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/

finder/details.php?id=1

and click on the link to apply for this degree.

Aims and Scope

The MSc provides biologists, conservationists,

horticulturists and ecologists with a wide

knowledge of plant biodiversity, as well as a

thorough understanding of traditional and modern

approaches to pure and applied taxonomy. Apart

from learning about the latest research techniques

for classification, students should acquire a

broad knowledge of plant structure, ecology, and

identification.

Programme Structure

This is an intensive twelve-month programme

and involves lectures, practicals, workshops and

essay writing, with examinations at the end of

the first and second semesters. The course starts

in September of each year and the application

deadline is normally 31 March.

Topics covered include:

• Functions and philosophy of taxonomy

• Evolution and biodiversity of the major plant

groups, fungi and lichens

• Plant geography

• Ecology of plants and ecosystems

• Conservation and sustainability

• Production and use of floras and monographs

• Biodiversity databases

• Phylogenetic analysis

• Population and conservation genetics

• Tropical field course, plant collecting and

ecology

• Curation of living collections, herbaria and

libraries

• Plant morphology, anatomy and development

• Cytotaxonomy

• Molecular systematics

Fieldwork and visits to other institutes are an

integral part of the course. There is a two-week field

course to a tropical country in which students are

taught field collection and identification of tropical

plants ecological survey techniques. The summer

is devoted to four months of a major scientific

research project of the student’s choice or a topic

proposed by a supervisor. These research projects

link in directly with active research programmes at

RBGE.

15

The Botanical investigations

of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

Marshall D. Sundberg

Department of Biological

Sciences

Emporia State University

Emporia, KS 66801

Key words: anatomy, wood, phloem, seeds,

sorus, sporangium

ABSTRACT

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek is well known for his

single lens microscopes and how he used them to

make observations on “little animals,” however, the

breadth of his botanical observations are less well

known. His thorough studies of wood anatomy

are well documented but he also reported on the

leaf anatomy, phloem, numerous seeds, and ferns.

This article is a summary of his major anatomical

findings as well as several of his physiological

experiments on plants, quantitative measurements

and predictions based on his observations, and

descriptions of the economic uses of some plants.

Leeuwenhoek and Oldenburg

Most of us are familiar with Leeuwenhoek

as a 17

th

century Dutch maker of single-lens

microscopes and discoverer of bacteria and

many “little animals,” protozoans and aquatic

invertebrates. (Dobell, 1932; Ford, 1991) You may

have observed that there are multiple spellings of

his name: “in the English versions of his epistles,

published in the Philosophical Transactions, his

surname is spelled in no less than 19 different

ways.” (Dobell, 1932, p.303) In this article I will

use the form chosen by the editors of The Collected

Letters of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a 19 volume

compilation by Dutch scientists, in Dutch and

English, of all of Leeuwenhoek’s correspondence

(Leeuwenhoek, 1939). (A recent article even

describes the construction and use of a “replica”

microscope by undergraduate students who then

used it to observe onion leaf peels and mosquitoes

(Sepel, Loreto, and Rocha, 2009). But it wasn’t

until I was invited by the late Larry Crockett to

perform with him in his unpublished three-act

play, “A Market Day in Delft,” that I learned of

Reports and Reviews

Leeuwenhoek’s relationship with Henry Oldenburg

and his series of botanical publications in the

Philosophical Transactions. This brief review of

Leeuwenhock’s botanical work is dedicated to the

memory of my friend, the late Professor Crockett:

botanist, thespian, teacher, and mentor.

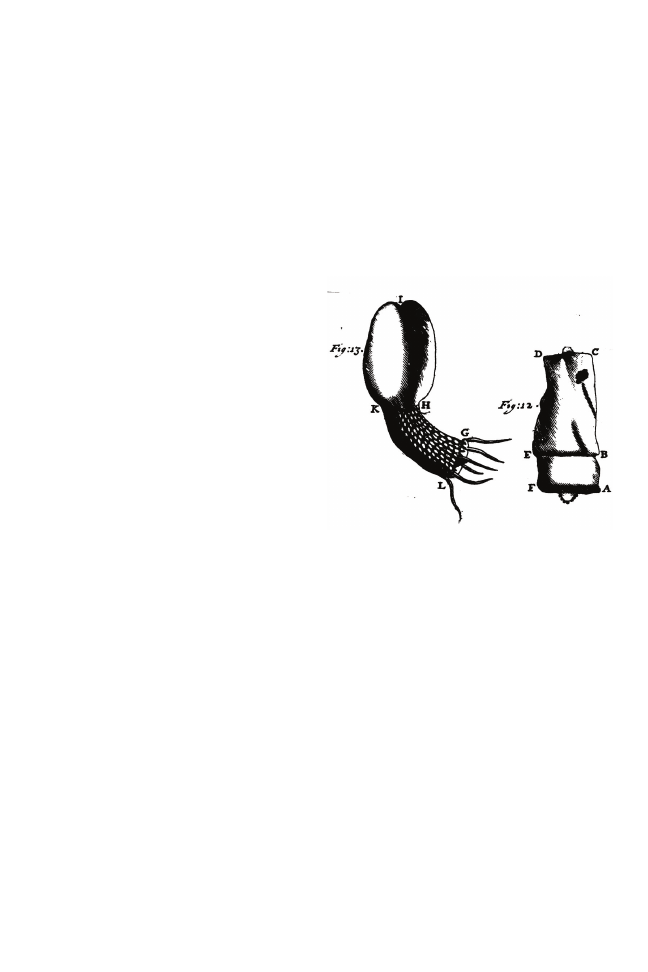

[Figure 1. Top, left to right, Larry Crockett (Leeuwenhoek)

and Marshall Sundberg (Oldenburg) in production of “A

Market Day in Delft” presented at the 1994 annual meet-

ing in Knoxville, TN. Bottom, left to right, Antoni van

Leeuwenhoek and Henry Oldenburg. Top image accessed

10/15/2010. http://botany.org/plantimages/Image-

Data.asp?IDN=35-125&IS=700]

In the Epistle Dedicatory to volume 8 (1673),

Henry Oldenburg noted that in this volume there

would be “…some Microscopical additionals

toevince the late improvement of that Instrument

in Holland….” Oldenburg was the founding

editor of the Philosophical Transactions (later the

Received: 11/1/2010; Accepted 2/9/2011

16

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

small Particles.” In the thicker material left behind

were the same small particles “of which the Leaf

were made up” and between these particles some

of the pipes “as I said I had seen in the Pores of the

Stalk of the Leaf.” If he held some of the thicker

material to a small flame, the particles burned away

but the pipes remained. Later he examined some

plain sap expressed form the leaves, and from the

stalk of the fruit after the leaves had “faded” and

in both of these exudates he found the little pipes.

“Now ‘tis likely, that these Pipes in this Herb are the

cause of the smart that is felt in chawing the Arum

by the motion of the moist Tongue in tasting.” (p.

381)

Later he noted “…that the motion of the sharp

Particles that are in some saps, was not less” [than

the “very pretty to behold” motion of the “little

globuls” he observed in the juice squeezed from

lemon peels]. (p 382) Furthermore, although

he observed small particles in the sap of many

plants, including ones shaped like “a well-polished

triangular or quadrangular pointed Diamond”, but

the “little Pipes” described in Arum were found in

only a few other plants such as the sap of “green

Vine-branches, and Asparagus…and very many

in the Sap of the Stalk and Leaves of Cataputia

(Spurge)…” (p. 382).

Unfortunately Leeuwenhoek provided no

sketches to support his descriptions in this paper,

but it is clear that he has described the parenchyma

(pores) in the petiole cross section. His “Pipes”

are raphid crystals, either free or clustered within

parenchyma cells, and he observed druses and

prismatic crystals in the expressed sap of other

plants. The “little globuls” with “very pretty motion”

were oil droplets from the glands of his lemon peel.

Wood Anatomy

The following year in his Epistle Dedicatory,

Oldenburg noted: “The curious Anatome of Plants

is here confirm’d, in some main Points, by good

Microscopes.” (Oldenberg, 1676). In this volume

Leeuwenhoek (1676b) included his first botanical

illustration, a detailed cross sectional image of an ash

twig, with an inset tangential section, to illustrate his

description of “the Texture of Trees.” (Interestingly,

the published image in the Philosophical

Transactions (Leeuwenhoek, 1676b) is a mirror

image of the figure Leeuwenhoek submitted in his

letter of April 21 (1676a). Leeuwenhoek’s studies

on wood anatomy are the one area of his botanical

work that is well documented in the literature (see

van Iterson, 1948; Baas, 1982) so I will only briefly

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society)

and in that capacity maintained a professional

correspondence with Leeuwenhoek regarding the

latter’s submissions, and sometimes requesting

work on specific topics. For instance, in Letter

No. 18 (Leeuwenhoek, 1675b) Leeuwenhoek wrote

“You had the kindness in your letter of October

26

th

1674 to ask me to examine the sap of plants. I

have examined several saps and observed in them

various figures, of which I have made rough drafts

on paper.” Oldenburg also acted as a go-between for

Leeuwenhoek to communicate with others. Four

months before submitting his first wood anatomy

paper, Leeuwenhoek wrote to Oldenburg: “Dear

Sir, I received your honoured letter of August 12

th

in good order, from which I learned that you have

received my letter of August 14

th 1

). I looked forward

to another letter in order to learn the opinion of the

Gentlemen Amateurs [Nehemiah Grew and Robert

Hooke] (to whom you will have communicated

my writings by now) on my theses, for I expect to

be contradicted, since the speculations set forth

in my letter, will appear strange to some people.

I will be greatly obliged if these objections are

communicated to me.” (Leeuwenhoek, 1675c) Of

particular value in the Collected Letters volumes

cited above are the extensive footnotes that explain

the biology, customs, interpretations, etc., such as

the apparent date inversion between Leeuwenhoek’s

letter and Oldenburg’s reply and the use of the term

“Gentlemen Amateurs” in the latter quotation. The

“microscopical additionals” Oldenberg referred to

was Leeuwenhoek’s (1673a) first contribution to

science, “1. The Mould upon skin…” and “2. The

sting of a Bee….”

Petiole Observations

Two years after his initial article, Leeuwenhoek

(1675a) published his first observations on plants.

He begins by noting that the sap of Arum (Wake-

robin) tasted “very sharp upon the tongue” and that

a cross section of the petiole contained “globuls

not exactly round” which themselves contained

“particles incomparably smaller.” Furthermore,

there were special parts “which I shall call Pores”

[parenchyma cells] and inside the pores were

“heaps” of 10 – 15 “small Figures” that were about

“the thickness of that of a Spiders Web,” but which

appeared to be about “the thickness of a great

Bread-knives back” in his microscope. He later calls

these small figures “Pipes.”[raphid crystals] If he

macerated some of the arum petiole and squeezed

the juice through bleu [filter] paper, nothing was

visible in the strained juice except an “abundance of

17

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

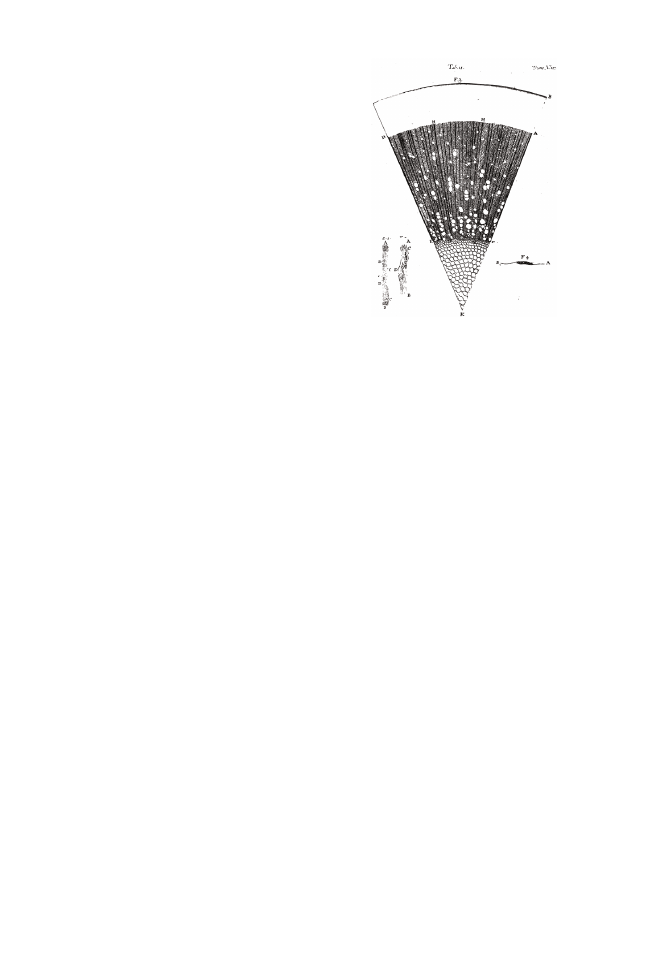

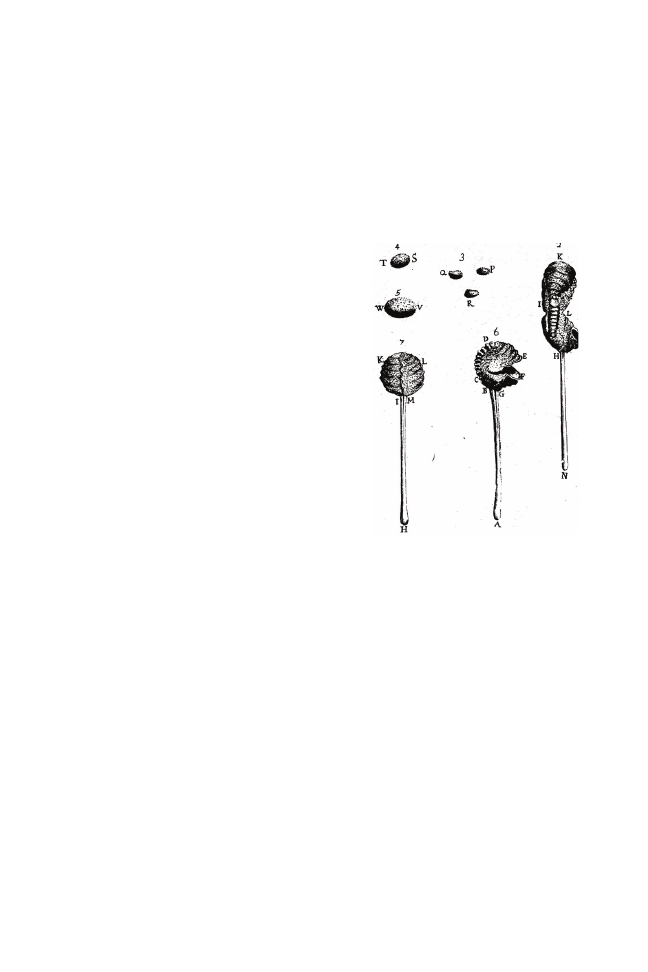

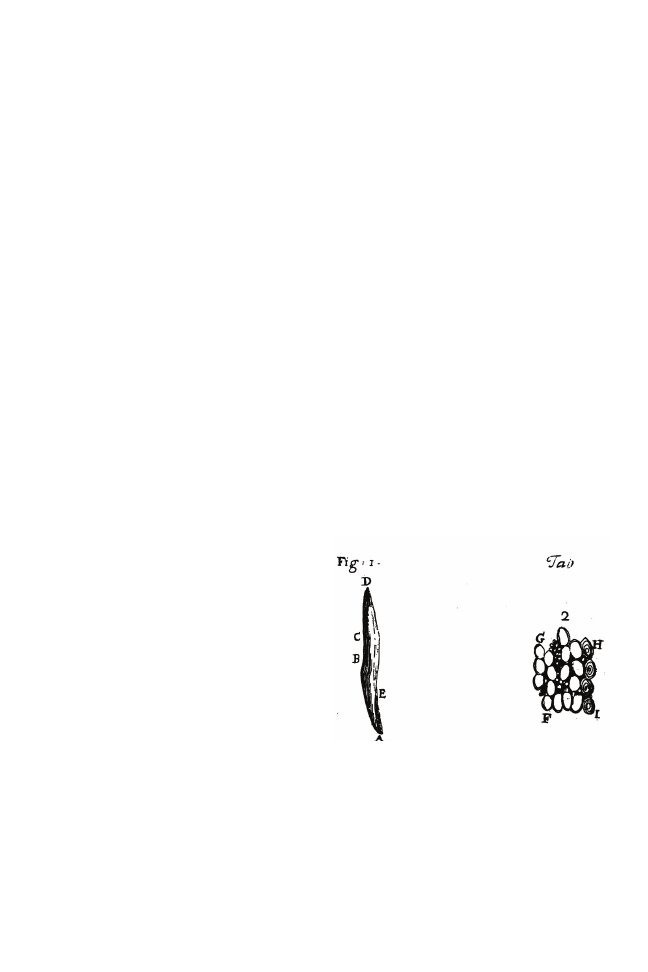

Figure 2. Ash wood, Leeuwenhoek (1676b). The largest

figure, 3, is the main sketch of a 1/8 transverse section of

a 1-year old ash stem with fine cellular detail in the pith

and xylem. Figure 1 is a radial section through an “upright

vessel” showing a short series of joined vessels with pitted

walls while Figure 2 is a tangential section illustrating two

fusiform multiseriate rays. (Figure 4 is of a nematode found

in the French wine, the description of which is the last para-

graph of the communication.)

Seven years later Leeuwenhoek (1683)

acknowledged that he was familiar with the

work of Malpighi and Grew, but nevertheless,

ventured “to represent the Vessels in Wood after

such manner as they offer’d themselves to me.”

(p. 198). In this wonderful paper he illustrates

and describes transverse and tangential sections

of six different woods: oak, elm, beech, willow,

alder, ebony, as well as palm and “straw” [probably

wheat]. Leeuwenhoek’s illustrations on a single

fold-out plate illustrate rectangular samples of the

woods, similar to the student laboratory slides we

use today. The transverse sections always include

a transition between growth rings except for the

ebony and palm, “…because that wood grows

in a Climate where it increases always: for the

Island Mauritius lies in a few degrees North of

the Tropic of Capricorn.” (p. 205). In each of the

figures, individual cells are clearly and accurately

represented; pit patterns and angle of the end

walls of vessels can be analyzed. Leeuwenhoek

distinguished between large multiseriate rays and

smaller uni-or biseriate ones, calling them two

types of “Vessels…lying horizontally.” (p 199)

Leeuwenhoek provided a clear description of the

describe some highlights here.

In August,1673, he sent a letter to Oldenburg

differentiating between pine wood, with one type of

“pipe” (tracheids) and describing two sizes of pipes

in the wood of oak. “I have likewise found two sorts

of holes or pipes, one larger (vessels) than the other,

in beech-, ash-, willow-, and vine-wood, as also in

sugarcane and rotan.” (Leeuwenhoek, 1673b). In

this letter he also described “tiny bands” (wood

rays) among the pipes, “white”(spring wood) and

“darker” (summer wood) areas with denser cells,

and speculated on the movement of fluids through

the pipes. The “valves” he describes are bordered

pits. This letter was not published.

Subsequently Leeuwenhoek had the opportunity

to examine Hugen’s copy of Grew’s “Comparative

anatomy of the trunks of plants” and based on the

figures in that text (Leeuwenhoek was unable to read

the English text) concluded that Grew was unaware

of the two types of vessels he had observed. This

was the reason for his illustrated 1676 paper. As a

preface, Oldenburg noted: “These observations, as

to the Texture of Plants, although they (and very

many more) have been already made and published

by Dr. Grew, and by Sign. Malpighi; yet because

that (for the most part) they may be a further

confirmation of the truth of their observations; I

thought it not unuseful to have them communicated

here also.”(Leeuwenhoek, 1675b,p. 656-7) (Grew’s

earlier publications including “Comparative

anatomy of the trunks of plants” were combined in

1682 to become the “Four Books” [sections] of his

Anatomy of Plants). Hutton et al.(1809) expanded

on Oldenburg’s original remarks to justify and

ensure Grew’s priority in describing the structure

of woody stems.

The issue of priority aside, Leeuwenhoek,

provided more accurate individual cellular detail

in his illustrations, particularly shape variation

where large vessels adjoin. His representations of

rays, as well as tyloses in some vessels, are clear and

accurate.

On at least one point, Leeuwenhoek provided a

better interpretation than either Grew or Malpighi,

both of whom stated that the large vessels, pores,

contained only air. Leeuwenhoek stated that “the

greater Vessels [true vessels] sent [sap] upwards,”

but he thought “that some small Particles did again

descend in the smaller Vessels [tracheids]….”

(Leeuwenhoek, 1675b, p. 653).

18

Plant Science Bulletin 57(1) 2011

are I guess about 20000 Vessels.

Hence in an Oak Tree of four foot

Diameter are 3200 Millions of

ascending Vessels, and in one of

1 foot, there are 200 Millions of

Vessels. If we suppose 10 of these

great and small Vessels in a day to

carry up 1 drop of Water, and that

100 of these drips make one Cubick

Inch, there will be 200000 Cubic

Inches. These Inches reduced to

feet, amount to full 115 Cubick feet of Rhinland

measure, of 12 inches to the foot; and one Cubick

foot weighing 65 lib. Of our Delph water, the whole

will amount to 7475 lib. Or 14 Bordeaux Hogsheads

[Bordeaux Hogshead = 220 liters] of water, which

a Tree of one foot Diameter in one day can bring

up. (p. 200).

(As an exercise in Biology of Plants this semester,

I challenged students to test Leeuwenhoek’s figures

by calculating the number of vessels per mm

2

on our oak slides. Only one student took up the

challenge - - her numbers, converted to English

units, were 68,000 cells/in.

2

.)

Fifteen years later Leeuwenhoek (1694) returned

to studying wood and made some observations

concerning the relationship between growth

rate, size, and wood strength. In this short letter

he questioned some of the common opinion

concerning the strength of wood based on his

understanding of wood structure and growth. For

instance, it was believed that timber cut in winter

was stronger than that cut in summer. However,

he noted: “that there is no difference, except in the

Bark and outermost Ring of the Wood, which in the

Summer are softer, and so more easily pierced by the

Worm.” (p 224). His most significant observation

was that the width of the annual rings is related

to growth conditions. “Some of these circles are

broader than others, particularly the Ninth, the

Tree from some accidental Cause receiving more

Nourishment, and growing faster that Year than the

former.” He said,

“he [a correspondent] examined a piece of Ash

growing in Norway, and found it grew 44 years

before its semidiameter was one Inch; whereas Ash

growing about Delft has been observed to increase

an Inch early for several years together.” (p. 225).

There is another 27-year span before

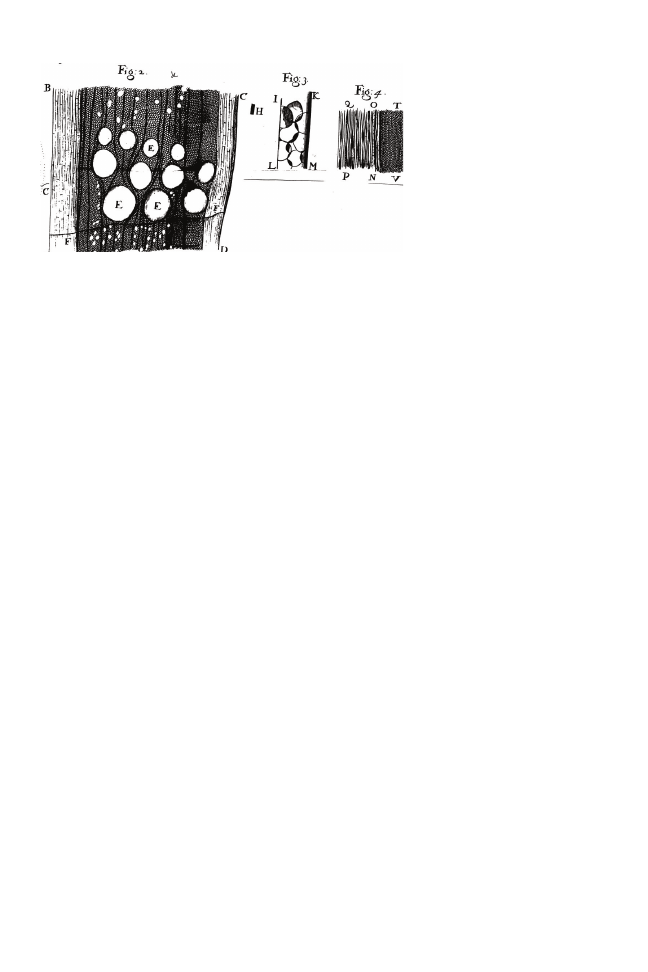

Figure 3. Oak wood sections, Leeuwenhoek (1683),

Figs.2, 3, and 4. Fig. 2, cross section at boundary of

growth rings. E, large vessels, F, multiseriate wood rays, G,

uniseriate wood rays. Fig. 3. Longitudinal section of vessel

containing numerous tyloses. Fig 4, Tangential section

with large multiseriate ray, T-V, pitted vessels, O-N, and

uniseriate rays, P,Q.

formation of annual rings and defines the concept

of “spring wood.” “EEE denote large ascending

Vessels made every year in the Wood in the Spring,

when it begins to grow. These are filled within

with small Bladders, which have very thin Skins,

here expressed in one of the greater Vessels, cut

long ways in the third Figure….” (p. 199). The

figure he refers to is a portion of an oak vessel, in

longitudinal section, with obvious tyloses filling

the lumen. Later, in willow, “… the great ones

[vessels] beset with little parts, seeming Globuls.”

(p. 204) He also described one sort of “rising

Vessels” as being “…also speck’t with parts which

by a common Microscope appear like Globuls, as

Fig 4. ON where one of the said Vessels is cult long-

ways.” (p. 199) Again referring to oak, this figure

is a tangential section where pitted side walls are

evident the length of the vessel running from O

to N, top to bottom of the image. This figure also

shows an area with numerous biseriate rays adjacent

to a large multiseriate ray. In elm he also describes

pitted vessels: “HH Shews one of the great rising