BULLETIN

SUMMER 2009 VOLUME 55

NUMBER 2

2@2

PLANT SCIENCE

ISSN 0032-0919

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Leading Scientists

and

Educators

since 1893

News from the Society

Upcoming Annual Meeting

Bringing the Food Back Home: Plants, Algae, Lichens and Fungi in the

Food Traditions of Indigenous Cascadia - Nancy J. Turner..............................50

Women in Science Luncheon and Discussion.....................................................51

BSA Science Education News and Notes...........................................................................51

Editor’s Choice...................................................................................................................54

Applications Solicited, Editor, Plant Science Bulletin, 2010 – 2014 .................................54

Supermarket Botany – A Fresh Approach........................................................................55

Announcements

In Memoriam

Peter Robert Bell 1920 – 2009.........................................................................55

William Ray Bowen 1936-2009........................................................................57

Bernard O. (Bernie) Phinney 1917-2009...........................................................57

Personalia

Peter Crane appointed Dean of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental

Studies...............................................................................................................59

Debra Edelstein Joins New England Wild Flower Society as Executive

Director..............................................................................................................60

Carnegie’s Arthur Grossman Receives Gilbert Morgan Smith Medal...............61

Nagib Nassar , BSA Member, Celebrates 50 Years Teaching And

Research.............................................................................................................61

Dr. Susan Pell, Brooklyn Botanic Garden Scientist, Returns from

successful Plant Research Expedition in Papua New Guinea............................62

Award Opportunities

Grants for Ornamental Horticulture..................................................................63

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings

I International Orchid Symposium, January 12-15, 2010, Taichung, Taiwan...63

56

th

Annual Systematics Symposium Missouri Botanical Garden....................64

VII International Congress of Systematic and Evolutionary Biology. ..............64

Other News

Lecture Celebrates Monumental Anniversaries of Two Botanical Gardens......................65

A Garden to Die For: Wicked Plants at Brooklyn Botanic Garden...................................65

Reports and Reviews

Botany at Eastern Illinois University................................................................................66

Books Reviewed................................................................................................................76

Books Received

..................................................................................................................................86

Botany & Mycology 2009

................................................................................................................88

50

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Botanical Society of America

Business Office

P.O. Box 299

St. Louis, MO 63166-0299

E-mail: bsa-manager@botany.org

Address Editorial Matters (only) to:

Marshall D. Sundberg, Editor

Dept. Biol. Sci., Emporia State Univ.

1200 Commercial St.

Emporia, KS 66801-5057

Phone 620-341-5605

E-mail: psb@botany.org

ISSN 0032-0919

Published quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 4475 Castleman Avenue, St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299. The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of

the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Periodical postage paid at St. Louis, MO and additional

mailing office.

News from the Society

Plenary Address

Bringing the Food Back Home:

Plants, Algae, Lichens and Fungi

in the Food Traditions of

Indigenous Cascadia

Nancy J. Turner

School of Environmental Studies, University of

Victoria, Victoria, B.C., CANADA V8W 2Y2

Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America

are identified by anthropologists mainly as fishers

and hunters. Yet, their traditional food systems

include many, diverse plant species, as well as

some marine algae, lichens and fungi. Plant foods

include roots and other underground parts, green

leaves and stems, many fruits, inner bark of trees,

and a range of beverage teas. These foods

collectively provide essential nutrients and have

been part of a healthy Indigenous diet over

thousands of years. The knowledge required to

use these nutritional resources effectively and

sustainably is part of an overall system of knowledge

that incorporates ecological understanding,

taxonomic, and biogeographical expertise,

specialized practices of harvesting, processing,

and maintaining resource populations, and belief

systems that guide their use and management.

Women have been the holders and practitioners of

much of this plant-based knowledge.

In recent years, for a variety of reasons, many of

these important Indigenous foods have been

declining in use, a dietary trend known as the

“nutrition transition,” that is occurring with local and

Upcoming Annual Meeting

Botany & Mycology 2009

Snowbird, Utah, 25-29 July

This issue continues our series featuring brief

histories of outstanding (or formerly outstanding )

botany departments. Cornell University (PSB 53-3)

and the University of Chicago (PSB 54-1) are major

research universities that are prominent and well-

known for preparing outstanding botanists to lead

the profession. Eastern Illinois University does not

produce Ph.D.’s but it also has a long history of

incubating young botanists and providing

outstanding botanical instruction. As an

undergraduate I was given a copy of Transeau,

Sampson & Tiffany’s Textbook of Botany that I could

use to “supplement” the newer textbook we were

using that was “weaker” in several areas (we were

using Cronquist’s Introductory Botany). I always

associated Transeau with Ohio State (and Otis

Caldwell with the University of Chicago). As you will

read, their formative teaching careers were spent at

Eastern Illinois where they laid the foundation for a

department that thrived until recently when it was

merged with Zoology. I hope you will find Jernegan

et al.’s article to be as interesting a read as I do.

And then the mergers - - the gradual but steady

demise of botany programs has been a concern in

these pages for several decades. In fact, I recently

contacted individuals at more than 60 institutions to

provide updated information about botany courses,

course enrollments, and botany graduates for the

past year (If you were contacted and have not yet

accumulated the data, it’s not too late - - please send

it in). The good news is that we are not alone in our

concern. The Chicago Botanic Garden recently

received a grant from the National Fish and Wildflife

Foundation to help support the “Botanical Capacity

Assessment Project.” Government agencies and

NGO’s are concerned that they cannot find personnel

adequately trained in organismal botany - particularly

taxonomy. We will have an important part to play in

generating data - - you will learn more, hopefully as

soon as the annual meeting in Snowbird.

-The Editor

51

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Editorial Committee for Volume 55

Joanne M. Sharpe (2009)

Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens

P.O. Box 234

Boothbay, ME 04537

joannesharpe@email.com

Nina L. Baghai-Riding (2010)

Division of Biological and

Physical Sciences

Delta State University

Cleveland, MS 38677

nbaghai@deltastate.edu

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

Jenny Archibald (2011)

Department of Ecology

and Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick (2012)

Department of Biology

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler (2013)

Department of Botany

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

schusse@muohio.edu

Indigenous Peoples’ food systems worldwide.

People who once gathered and prepared healthy

local food are turning towards more processed and

marketed foods many of which are high in unhealthy

fats and refined carbohydrates. The result is

increased risk of diabetes and heart disease and

other health problems. Today, Indigenous

communities are using a range of strategies to

maintain and strengthen their use of their original

foods, and have found partners in universities,

NGOs, and government agencies to support this

endeavor. In this presentation, I will describe some

of the diverse Indigenous “wild” foods of the

Cascadia Region, including Angiosperms,

Gymnosperms, and some Algae, Lichens and

Fungi, and discuss the ways in which Indigenous

Peoples have maintained and enhanced these

resources, what has happened to these food

species, and how they are now being reclaimed

and re-incorporated into Indigenous Peoples’

foodways.

Women in Science

Luncheon and Discussion.

The Women in Science Luncheon will be followed

by a panel discussion. Women scientists from

different botanical disciplines and different

backgrounds and career paths will discuss their

experiences. The panel will also respond to

questions from the audience. The organizers

especially encourage their male colleagues to attend

and participate. For more information contact:

Soltis, Pamela S. - University of Florida, Florida

Museum of Natural History, PO Box 117800,

Gainesville, FL, 32611-7800, U.S.A.

Hirsch, Ann M. - UCLA, Department of MCD Biology

and Molecular Biology Institute, 405 Hilgard Avenue,

Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1606, USA.

Poston, Muriel E. - Skidmore College, Biology

Department, 815 N. Broadway, Sarasota Springs,

NY, 12866, USA.

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a

quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts

and the broader education scene. We invite you to

submit news items or ideas for future features.

Contact: Claire Hemingway, BSA Education

Director, at

chemingway@botany.org

or Marshall

Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org.

PlantingScience — BSA-led student research and

science mentoring program

Watch Us Grow!

That is the line on the T-shirts PlantingScience

teachers and mentors received for participating in

the mentored inquiry sessions. If you served as a

mentor in the Fall or Spring Online Session and did

not receive a T-shirt, let us know. T-shirts,

Certificates of Meritorious Service, and letters of

support are small tokens of our appreciation for your

contributions to change the way students experience

and understand science.

52

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Thanks to you, ~2,140 students in 55 classes had

the opportunity to communicate online with scientists

while conducting plant investigations in their

classrooms. Interest in the project continues to rise

at a rapid pace (another doubling in participation

this year). Your volunteer efforts make this program

possible!

Have you wondered what impact this student-

teacher-partnership might have?

Here are a few thoughts from participants.

“ … Thank you so much for being a great mentor.

You really helped us learn alot! Planting science

was a great way for us to be a part of science! Thanks

agian!” — St. Rose of Lima student

“The part I most liked about this experiment was

communicating with our mentor and learning things

from her. I also liked how other people from other

teams commented our page and how we

commented there page.” — Marshall Middle School

student

“Just wanted to let the mentors know what a fantastic

job they are doing. I love how they are actually

‘guiding’ my students through the scientific thinking

process and not simply telling the students what to

do. Even though some of my students are a bit

frustrated, I like the ‘thinking’ that is going on in their

minds.” — Mark Hurst, Galena High School teacher

“My kids have been really excited…Thanks to ALL

of you for your time to help the kids!...they are

working in small groups, they are discussing and

asking questions-which is GREAT!! I’ve seen that

many have also logged in during non-school hours.

wow.” — Jennifer Forsyth, Woodstock High School

teacher

Over the summer, we will be busy offering teacher

workshops, recruiting new teachers and mentors

for the fall session, and making project

improvements. Please send any suggestions to

psteam@plantingscience.org.

2008 Master Plant Science Team Recognition —

Call for 2009-2010 Applications

Members of the Master Plant Science Team are a

special group of primarily graduate students who

receive a few perks for their commitment to serve for

an academic year and mentor ~4 teams in both the

fall and spring session.

Our deep thanks to the 2008-2009 Master Plant

Science Team. We are grateful for the insights and

extra efforts of those field-testing new inquiries

(underlined below).

The Botanical Society of America sponsored:

Rob Baker, Alona Banai, Katie Becklin, Michelle

Brown, Marian Chau, Nick DeBoer, Frank Farruggia,

Kelly Gillespie, Jennifer Gray, Kandress Halbrook,

Dr. Diana Jolles, Rucha Karve, Rachna Kumar,

Courtney Leisner, Dr. Jason Lando, Julia Nowak,

Amber Roberston, Dr. Aurea Siemens, Roxi Steele,

and Genevieve Walden.

The American Society of Plant Biologists

sponsored:

Brunie Burgos, Eliana Gonzales-Vigil, Lisa Kanizay,

Josh Rosnow, and Ashley Spence.

Would you like to join the 2009-2010 Master Plant

Science Team? Graduate students and post-

doctoral researchers are particularly invited to apply.

For information on perks, requirements, and an

online application form, please see the Scientist

page on

www.plantingscience.org

. Or use the link

below.

h t t p : / / w w w . p l a n t i n g s c i e n c e . o r g /

index.php%3Fmodule=pagesetter%26func=

viewpub%26tid=4%26pid=62

Spotlight on PlantingScience Teachers’

Acheivements

Our hats are off to several teachers in the

PlantingScience program for honors and

recognition they have received for their contributions

to education. Congratulations. Kudos to you.

Naomi Volain – Teacher of the Month in Springfield,

Massachusetts Public Schools, Information and

Instructional Technology Solutions Department.

53

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Naomi participated in last year’s inaugural

PlantingScience Summer Institute, and then in both

the fall and spring online sessions. Naomi has a

long-standing interest in integrating technology in

the classroom and involving students in participatory

science projects, including Forest Watch (from her

alma mater, University of New Hampshire) and

ground-truthing cloud observations for the NASA

CERES S’COOL.

Dr. Michael Hotz – Recipient of Teaching

Environmental Stewardship Award from Science

Pioneers, and his school Wyandotte High School

wins the Kansas Green School Award from the

Kansas Association of Conservation and

Environmental Education.

they strive to support promising students in their

community to pursue independent research through

out their high school years. Read more about the

Fellows Program:

http://www.societyforscience.org/outreach/

FellowsMarch09.pdf

Valdine has been a part of PlantingScience since

2005, and active in developing and field-testing new

inquiry units.

Participating in the Summer Institute and online

session are just a few of Mike’s green education

activities in his school and across the district. The

courtyard gardens, flower and vegetable gardens

he built on the school grounds provide enriching

outdoor learning experiences.

Valdine McLean, Tamica Stubbs, Cappi Coleman

– Society for Science and the Public Fellows.

Ten high school teachers from across the country

were selected to build independent scientific

research in their underserved communities. Three

of the ten members in the inaugural class of the

SSP’s Fellows Program are Planting Science

teachers. What a showing! We wish them well as

Tamica joined the PlantingScience Summer Institute

last year.

Cappi Coleman has participated in PlantingScience

since 2007.

54

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Science Education in the News

Nine steps to transform agricultural education in the

face of changing times — Solving many of today’s

societal problems will rely on innovative

interdisciplinary approaches to scientific agriculture.

The recently released National Research Council

report, Transforming Agricultural Education for a

Changing World, recommends a suite of steps for

colleges and universities with undergraduate

programs in agriculture to prepare students for the

evolving agricultural workplace.

http://www.nationalacademies.org/ag_education

More underrepresented minorities earn PhDs in

science — Hard data show payoffs in programs

aiming to boost participation of underrepresented

minorities in science, technology, engineering, and

math (STEM) fields, according to the recent AAAS

report. The annual percentage of PhDs awarded

across all STEM fields to underrepresented

minorities rose to 33.9% among the 66 institutions

in the Alliances for Graduate Education and the

Professoriate (AGEP). In the biological and

agricultural sciences, the percent of PhDs awarded

to minorities in 2008 increased to 55.9%, up from

38.3% in 2001.

http://nsfagep.org/publications.php

[pdf of report

available under Info Briefs]

http://www.aaas.org/news/releases/2009/

0401minority_phd.shtml

[news release with video

of Shirley Malcom discussing the good news]

What do American adults understand about basic

science? — Unfortunately, only one in five American

adults could answer basic science questions about

life on planet Earth, according to a national survey

commissioned by the California Academy of

Science. Only 53% of respondents know how long

it takes Earth to revolve around the Sun. How does

your science understanding compare? A link to the

online quiz is available on the California Academy

of Sciences’ website.

http://www.calacademy.org/

Editor’s Choice

Chanchaichaovivat, Arun, Bhinyo Panijpan and

Pintip Ruenwongsa. 2008. Yeast biocontrol of a

fungal plant disease: a model for studying organism

relationships. Journal of Biological Education 43(1):

36-39.

This activity demonstrates the inhibitory effect of the

yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, on growth of the

fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea both in culture and

when inoculated into wounds on fresh red chili

peppers.

Catley, Kelyn M. and Laura R. Novick. 2009. Digging

Deep: Exploring college students’ knowledge of

macroevolutionary time. Journal of Research in

Science Teaching 46: 311-332.

Student questionnaires in a multi-problem booklet

were used to survey students in a large class at a

private research university and a small class in a

private science and technology university. The

students had a range of previous science

coursework from only an introductory course to

several courses including an upper-level course in

evolution. All students underestimated the time

since major historical events (age of the earth, 1

st

fossils, eukaryotic cells, Cambrian explosion, 1

st

mammals, dinosaur extinction, and 1

st

hominids.

Most discouraging was that there was no significant

difference between students with little background,

science majors, and science majors who had

completed an evolution course!

Applications Solicited, Editor, Plant

Science Bulletin, 2010 – 2014

Are you looking for a meaningful way to serve the

Botanical Society of America? Are you interested in

desktop publishing? Would you like to correspond

with botanical colleagues in many disciplines about

books, articles, and matters of interest to the BSA?

The BSA is soliciting applications for the 5-year

position as Editor of the Plant Science Bulletin.

If your answer to ANY of these questions is yes,

please communicate your interest to Dr. Pat

Herendeen (Chair, BSA Publication Committee).

PATRICK HERENDEEN, Chicago Botanic Garden,

1000 Lake Cook Road, Glencoe, 60022 Phone:

202/994-5828, 847-835-6956. E-mail

pherendeen@chicagobotanic.org

Applications are welcome any time and no later

than July 1, 2009. The BSA Publication Committee

will begin reviewing interested candidates during

summer of 2009.

For a description of the Plant Science Bulletin see:

http://botany.org/plantsciencebulletin/

55

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

.

Announcements

In Memoriam:

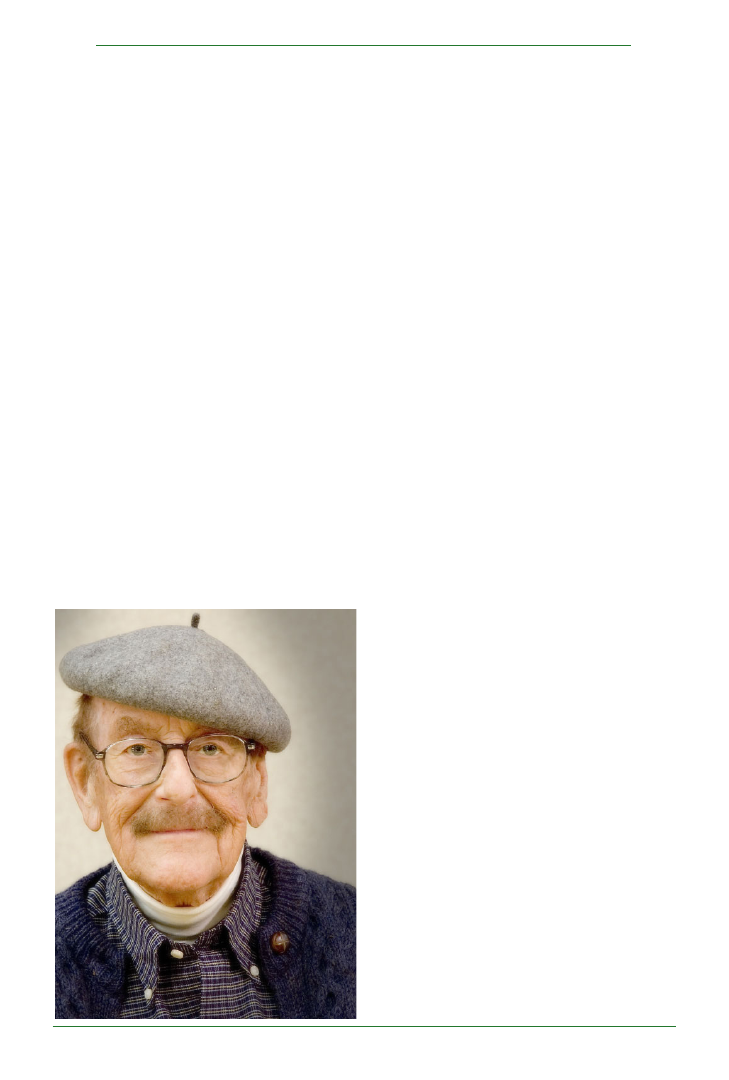

Peter Robert Bell

1920 – 2009

Peter Bell, who has died at age 88, was a leader in

the study of the reproductive biology of ferns and

gymnosperms, a pioneering electron microscopist,

and author of the widely-read ‘Diversity of Green

Plants’. He spent much of his career at University

College London, as Professor, Quain Professor

and Head of the Department of Botany and

Microbiology, and Chairman of the Faculty of Science.

Peter was a proud and dedicated botanist and

enthusiast for all of plant life. An enduring interest

in the pteridophytes meant that, for him, Lycopodium,

Selaginella and each of the ferns held great

fascination and wonder. The ‘alternation of

generations’ became the center of Peter’s research

interests. He aimed to understand the changes in

gene expression that accompanied the transition

for sporophyte to gametophyte and back again, and

how these changes were organized to establish the

nature of the generations. He took this on in the

decade before the advent of molecular biology, and

used the techniques of the day, including

autoradiography and early immunocytochemistry,

to search for answers.

His studies involved analysis of the antherdia and

archegonia that were borne by the gametophytes,

fertilization, and the nature and development of the

zygote. Peter became convinced that biochemical

isolation of the cells that gave rise to the gametes

was essential to separate the gene expression of

the gametophyte from that of the gametes and

therefore of the sporophyte that they combined to

establish. This isolation was to be followed by a

purging of the gamete cytoplasm of the RNAs that

were characteristic of the gametophyte, and their

replacement with others that were necessary to

build the very different nature of the sporophyte. It

was in this way that Peter envisioned the sweeping

biochemical changes that stimulated the ‘phase

change’, and that he held were at the center of the

control of the alternation of the generations.

Peter’s work was published widely and includes

more than 100 papers. His ‘Diversity of Green

Plants’ set some of his own work into the broader

context of plant evolution from the algae through the

flowering plants; reprinted several times, this

remains a standard text at colleges and universities

through Europe and the US.

Supermarket Botany – A Fresh

Approach

Geoff Burrows and John Harper

Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga

gburrows@csu.edu.au

&

jharper@csu.edu.au

The use of Supermarket Botany is a popular

approach to teaching plant structure and plant life

cycles. It uses a student’s existing knowledge of

everyday food items to explore the differences

between:

·

fruit and vegetables,

·

roots, stems and leaves, and

·

flowers (with ovaries and ovules) and fruits

(with seeds).

We aimed to produce a resource that was botanically

accurate, with a reasonable level of detail and that

was presented in an engaging format. Please see:

http://www.csu.edu.au/research/grahamcentre/

education/

The web site is divided into two main areas:

· a tutorial that explains the differences between

roots, stems and leaves, and also examines the

differences between vegetative and reproductive

tissues, and

· a test (called ‘The Challenge’) that allows students

to apply the knowledge gained in the tutorial.

In ‘The Challenge’ students select an item from

‘The Shelf’ and are then required to select whether

its major component is root, stem, leaf, flower, fruit

or seed. We have done extensive surveys and have

identified the common Supermarket Botany

misconceptions. Thus we are able to customise

the incorrect answer responses to give hints as to

the correct answer. Once the correct answer is

selected students go to the ‘Why?’ page, where

high-quality images provide supporting evidence.

Quantitative testing indicates the web application

has similar learning outcomes to a traditional

laboratory-based session, although it is designed

to support, not replace, hands-on learning. Student

responses include “I understood more in 15 min

(using Supermarket Botany) than 2 hours of textbook

reading.”

56

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

great disappointment that never left him. For many

of his later years, Peter lobbied single-handedly to

restore the Quain chair and the department, only

giving up his campaign when enfeebled by age.

Throughout his career and his life, Peter lived

simply and with great independence. His lab,

overlooking Gower Street and on the site of Darwin’s

London residence, boasted fine wooden surfaces

for bench, desk and cupboard, although an alarming

absence of equipment other than microscopes,

and little in terms of technical help or administrative

support – Peter was fond of saying that instruments

were very good substitutes for ideas, and that the

state of decay of a Department could be best

measured by the degree of proliferation of the

secretaries. At home, Peter took great pride in

paneling bathroom, attic and study, measuring

each panel in its anticipated location, taking said

panel to garden, cutting and preparing it, and

screwing with great precision in to place. Lamps,

chairs, and knife and fork handles were fashioned

similarly, fireplaces copper-plated, and

conservatories and greenhouses built! A cistern in

the garden collected rainwater, kitchen refuse was

composted, salads grown, and apples and

damsons turned to jam and jelly.

Peter taught himself German, so that he could read

Hofmeister in the original, and maintained great

enthusiasm for all things German, including his

adored Siemens electron microscopes and BMW

motor cars, throughout his life. He read Die Zeit

every day, with a Wahrig German dictionary in easy

reach. When confronted by a graduate student (RP)

exclaiming an interest not in German but in French,

Peter – with great deliberation – would exclaim ‘But

for what possible reason? And such a (with

exasperation) ‘barbaric language!’

Peter traveled and ‘botanized’ widely. He was fond

of saying that ‘only by visiting the tropics can we see

what plants can really do’. He spent a sabbatical

year at Zurich and one at UC Berkeley, where he

came to admire the great morphologists Ernest

Gifford and Don Kaplan. He loved the mountains of

Europe and the US and maintained enormous

affection for Switzerland and California throughout

his life. Ireland, through Elizabeth’s heritage, Spain

and the northeast of England through Jerry and

Mike Bell’s relocations, were also special places.

The Rioja of Cosme Palacio was Peter’s other

enduring pleasure, and his visit to the La Guardia

winery was the center of his last visit to Spain.

Late in his career, Peter became a visitor to

Buckingham Palace. Once, on the day after an

evening at the Palace, he offered one of us (RP) this

clear advice: ‘Now, Roger, remember this. If ever

Peter took a First class degree in Natural Sciences

from Cambridge.

Peter was a Quaker, and from an early age he held

very strong pacifist beliefs. During the war he was

a conscientious objector, and in the early days of the

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, in 1960, was

brought to court for refusing to pay the part of his

income tax that he calculated would be used by the

Government to build nuclear armaments.

Arriving at University College at the very end of the

war, Peter became a part of a coterie of plant

science leaders and thinkers, including Dan Lewis

and Jack Heslop-Harrison, who made the

Department of Botany and Microbiology a center for

plant science research through the 1970s and early

1980s. When the focus shifted toward medical

science in the 1990’s, the Quain chair of Botany (of

which Peter was a prior occupant) remained unfilled,

and when the Department of Biology replaced

Peter’s beloved ‘Botany and Microbiology’, he felt a

Peter Bell was born to a humble family in Whitstable

in Kent, south of London, on February 18, 1920. His

father Andrew was a market gardener who

specialized in tomatoes and apples. His mother

Mabel used the vegetables with which she was

surrounded to develop a quintessentially British

style of cooking – organized around a piece of grilled

or roasted meat served with potatoes, a green

vegetable, and gravy, and with an apple pie or

similar for desert – that both Peter and Elizabeth Bell

continued to practice throughout their lives; these

were taken to the pinnacle of development so that

dinner parties at the Bell household, were notoriously

British but more notoriously delicious.

57

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

you are invited, under no circumstance need you

hesitate to accept’.

Peter died of Parkinson’s disease on January 10,

2009, in London. He leaves Elizabeth and Mike Bell

in London, and Jerry Bell in California.

-Roger Pennell – Los Angeles

rpennell@ceres-inc.com

-Hugh Dickinson – Oxford

hugh.dickinson@plants.ox.ac.uk

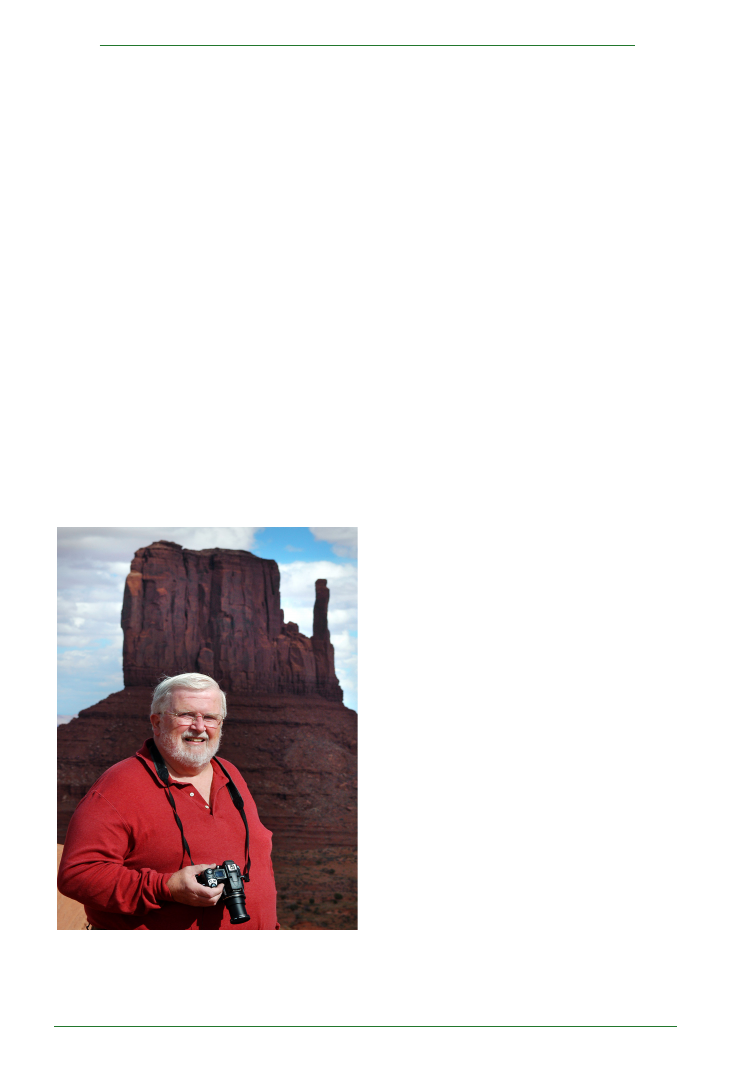

William Ray Bowen 1936-2009

William Ray (Bill) Bowen, 72, of Maumelle, passed

away at his home Monday, January 19, 2009 following

a long battle with cancer. Survivors include his

beloved wife of 48 years, Janet Bowen; two sons,

Jeffrey Bowen and his wife, Lori, of North Little Rock,

and Scott Bowen and his wife, Kelly, of Little Rock;

grandsons Hunter Bowen and Austin Bowen;

granddaughter, Emma Bowen; and two brothers,

Robert Bowen and John Bowen of Springfield,

Missouri. A sister, Barbara, preceded him in death.

Mr. Bowen was born October 15, 1936, in Iowa City,

Iowa, to the late Esther and William Bowen. He

earned a BA in biology from Grinnell College (Iowa)

in 1960 and an MS and PhD in botany from the

University of Iowa in 1964. He taught botany/biology

at Western Illinois University and Ripon College

(Wisconsin) before joining the faculty of the University

of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) in 1975. In 1990,

he joined Jacksonville State University in Alabama

as Head of the Biology Department. He was

instrumental in the modernization of the department,

and in creating the Little River Canyon Field School

and the Little River Canyon Center, a facility shared

with the National Park Service. Mr. Bowen retired

from JSU as Professor Emeritus in 2001 and, in

2002, he and his wife returned to Arkansas.

During his lifetime, Bill was an avid tennis player

and amateur photographer. After relocating to

Maumelle, he participated in the Pulaski County

Master Gardener program and he and Jan developed

a backyard wildlife garden. Together they enjoyed

travel to the western states, Canada, Europe,

Australia, New Zealand, China, Tibet, and Central

and South America.

The family requests that memorials be made to the

JSU Foundation, William R. Bowen Student

Research Fund, c/o Biology Department,

Jacksonville State University, 700 Pelham Rd, N.,

Jacksonville, Alabama 36265.

Bernard O. (Bernie) Phinney 1917-

2009

UCLA and plant biology lost an important member

of their respective communities with the death of

Bernard O. Phinney of heart failure on April 22, 2009

in Los Angeles. Bernie was born July 29, 1917 in

Superior, Wisconsin. He earned a B.A. in 1940 and

a Ph.D. degree with Ernst C. Abbe as his advisor at

the University of Minnesota in 1946. While a Ph.D.

student, Bernie heard a seminar given by George W.

Beadle, which so impressed him that he went to

Caltech to work with Beadle as a postdoctoral

researcher from 1946-1948. It was this experience

that led Bernie to make major scientific contributions

towards understanding the function and metabolism

of gibberellins. His observations were some of the

first to show that this class of plant hormones, which

affect such critical developmental phenomena as

seed germination, stem elongation, and fertilization,

could be understood using a biochemical genetics

approach.

In 1947, Bernie was hired as an instructor at UCLA,

went through the professorial ranks, and became a

58

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Bernie earned numerous awards during his career

including a Research Medal from the International

Plant Growth Substances Association (1982), and

the Stephen Hales award from the American Society

of Plant Biologists (ASPB) (1984). In 1985, he was

elected to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

Bernie received a Certificate of Merit for “meticulous

research in plant physiology” (1986) and a

Centennial Award from the Botanical Society of

America (2006). He joined the BSA in 1946 and

remained a member his entire life. He was elected

Honorary Foreign Member of the Japanese Society

of Chemical Regulation of Plants (1988). Bernie

was elected and served as the President of the

ASPB from 1989-1990 and was honored as a

member of the inaugural class of ASPB Fellows in

2007. In 1989, he was awarded an Honorary D.Sc.

from the University of Bristol in the U.K., and a

Research Fellowship from the Japanese Society

for the Promotion of Science in 1991.

Bernie became Professor Emeritus at UCLA in

1988 but he did not slow down. He continued his

research and outreach activities until about two

weeks before he died. Well into his 90’s, Phinney

continued his research in the UCLA Plant Growth

Center, usually testing an extract of marah

(Cucurbitaceae) on dwarf mutants of Arabidopsis.

He also tested various gibberellins on some dwarf

mutants of Melilotus alba Desr. (white sweetclover)

that my lab studied. Bernie loved our new Plant

Growth Center and spent a great deal of time

working with his plants, almost daily. It was very

important for him to keep on doing research even

after years of retirement. After being in the Botany

Building for more than 40 years, his office was

moved to the 3rd floor of the Life Sciences Building

near other labs working on Arabidopsis. Here he

had the opportunity to interact with graduate

students and postdocs, helping them by writing

them letters of recommendation, and giving advice.

He loved relating anecdotes about science and

stories about people he had know.

In addition to his enthusiasm for plants, especially

for the ferns and orchids that he grew in his home

greenhouse, Phinney loved skiing, fishing, eating

sushi (actually, he liked everything Japanese,

including art and architecture), and listening to

classical music, often when driving in his fiery red

convertible with the top down. He used to drive a VW

camper with the license plate GA1. As a one-time

passenger in this vehicle, I can tell you that driving

down Wilshire Boulevard with Bernie at the wheel

was an experience not to be forgotten.

His wife Jean; four children, Scott Phinney, Katcha

Burnett, Peter Phinney, and David Phinney; and

eight grandchildren survive him. The Phinney family

will be holding a memorial service for Bernie at their

full professor in 1961. It was during his early years

at UCLA, however, that Bernie began to test the

concept of linkage between phenotype and

genotype. In this research, he showed that dwarf

mutants of maize became tall if given an external

application of gibberellin, showing that dwarfness

was linked to a deficiency of this hormone. Because

maize dwarfness segregates as a Mendelian

recessive, the results strongly suggested that the

mutation occurred in a single gene. This seminal

research paper was published in 1956 in the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The findings were so insightful that they were later

incorporated into textbooks along with the classic

picture of dwarf maize before and after gibberellin

treatment. A 1957 paper in the same journal co-

authored with Charles A. West, Mary Ritzel, and

Peter M. Neely of UCLA identified gibberellin-like

substances from a number of different families of

angiosperms. Although Japanese scientists had

already discovered gibberellin production by the

fungus, Gibberella fujikuroi, the causative agent of

“foolish seedling disease”, Bernie and his graduate

student Calvin Spector identified a gene controlling

a step in gibberellin biosynthesis. These three

papers set the stage for Bernie’s lifelong synthesis

of chemical, genetics, and physiological

approaches to answer research questions. He

and his co-workers, many from the U.K. such as

Jake MacMillan and Clive Spray, or from Japan,

Nobutaka Takahashi, Saburo Tamura, and

Masayuki Katsumi, later elucidated the various

biochemical pathways required for the synthesis of

several distinct gibberellins.

59

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

home in Los Angeles, CA on Saturday, May 30, at 3

p.m. Contributions in Bernie’s memory can be sent

to: the Bernard and Jean Phinney Graduate

Fellowship in Plant Molecular Biology, University of

Minnesota Foundation, 200 Oak St SE, Suite 500,

Minneapolis, MN 55455.

-Ann M. Hirsch, Department of Molecular, Cellular

and Developmental Biologoy, UCLA, Los Angeles,

CA.

May 1, 2009

Bernie and I got to know each other one hot summer

(in the early 50s) in the cornfields of Minnesota. I

was a grad student, he a relatively new Ph. D. We

were charged with propagating Ernst Abbe’s dwarf

corn stocks. I have no doubt that observing the

diversity of dwarfs expressing differently on four

different inbred lines must have tweaked his

scientific curiosity. I remember him as a friendly,

sociable person, always showing concern for the

individual. Thus at scientific meetings, he did not

take kindly to people who would leave the room

before the last (often young) speaker was finished.

His interest in people persisted throughout his life.

He was careful in preserving his individuality whether

in unusual clothing or riding in his convertible car,

which ran on bald tires. It did serve him well,

however, in attracting good-looking coeds!

At the end of the summer, Bernie left for the West,

carrying with him some of the corn. He did well until

he was stopped at the Arizona-California border by

agricultural inspection and told to shell all the corn

off the cobs. Bernie spent the day there shelling

corn!

We continued to keep in touch—primarily through

science meetings but also when he came East to

visit relatives. On the way, he would always stop by

the old botany building and visit with his (and mine)

old advisor, Ernst Abbe. One summer it misfired.

Bernie had come to collaborate with Abbe on a

paper. Abbe decided to spend his time refinishing

the floors of his house instead. Bernie was not

amused. But to his credit he continued his loyalty

even to Abbe’s last years, when visiting him surely

must not have been easy.

All of us rejoiced when Bernie became a member

of the National Academy. Being Bernie, this honor

did not change him—he continued to be the same

decent and modest person we all knew.

-Otto L. Stein, 140 Red Gate Lane, Amherst, MA

01002

413-253-9572

Personalia

Peter Crane appointed Dean of the

Yale School of Forestry and

Environmental Studies

(Media-Newswire.com) - New Haven, Conn. —

President Richard C. Levin has appointed the

distinguished evolutionary biologist Sir Peter Crane

as dean of the Yale School of Forestry and

Environmental Studies.

The John and Marion Sullivan University Professor

in the Department of Geophysical Sciences at the

University of Chicago, Crane is the former director

of England’s renowned Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew. Earlier in his career he also led the scientific

programs at the Field Museum of Natural History in

Chicago.

“Peter’s impressive record of research and

conservation achievements and his stellar

leadership of important scientific organizations will

make him a superb dean of Yale’s environment

school,” Levin said. “I am confident that he will add

to the school’s century-long legacy of leading

research and education in an era when advancing

knowledge of the natural world and mankind’s

impact on it has never been more important.”

Crane’s research is focused on the diversity of plant

life; its origin and fossil history, its current status,

and its conservation and use. Seeking to understand

large-scale patterns and processes of plant

evolution, he has worked extensively on questions

relating to the origin and early diversification of

flowering plants and, together with Paul Kenrick,

published “The Origin and Diversification of Land

Plants” in 1997. He has written several other books

and nearly 200 articles and essays.

Prior to his current appointment at the University

of Chicago, Crane served from 1999 to 2006 as

director and chief executive of Kew, one of the

most influential botanical gardens in the world.

At Kew, which has the world’s largest and most

comprehensive collection of living plants, Crane

worked on the initial establishment of the

Millennium Seed Bank and a variety of other

programs in plant conservation.

He directed the Field Museum from 1995 to 1999,

where he established the Office of Environmental

Programs and had overall responsibility for the

museum’s work in science and conservation. His

association with the Field Museum began in 1982,

and he served as curator, department chair and

vice-president. At the University of Chicago, Crane

was a professor in the Department of the

60

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Debra Edelstein Joins New

England Wild Flower Society as

Executive Director

Framingham, MA - New England Wild Flower Society

announced today the appointment of Debra

Edelstein as its Executive Director. Society Board of

Trustees Chair Frances H. Clark stated, “The Board

of Trustees is delighted to welcome Debbi as the

new leader of New England Wild Flower Society.

She brings a deep commitment to conservation

and a breadth of experience in managing non-profit

organizations. We were impressed by her

enthusiasm, expertise, and creativity and voted

unanimously for her to lead us in the challenge and

excitement of these coming years. The native plants

will thrive under her charge.”

Edelstein started February 17 and manages the

Society’s headquarters and staff at the 45-acre

botanical museum Garden in the Woods,

Framingham; Nasami Farm and Sanctuary,

Whatley; conservation programs; education

programs; and ten sanctuaries located throughout

New England.

In her most recent position at NESCAUM, the

regional organization that provides scientific and

policy expertise to the air agencies of the eight

Northeastern states, she established a new

collaborative effort by the states and the US EPA to

reduce diesel emissions, secured $15 million in

new project funding, created industry workgroups

and multi-state task forces, and organized

successful public workshops.

As Vice President and Executive Director of National

Audubon Society/Audubon Washington, she

published the country’s first “State of the Birds”

report, garnered a unanimous legislative vote for a

first-in-the-nation state law adopting Audubon’s

Important Bird Areas into the Natural Heritage

Database used for land use and management

decisions on both public and private land, produced

the first “State of Environmental Education” report at

the request of the Washington legislature, and

provided fiscal stability to Audubon Washington.

As Bioreserve Project Manager for The Trustees of

Reservations, she led the Trustees’ role in creating

the 13,600-acre Southeastern Massachusetts

Bioreserve, the Commonwealth’s largest land-

protection project.

She has also been a consultant offering

environmental planning, education, and

communication services, a marketing director,

editor, and writer. She holds a MCP (Master in City

Planning) in Environmental Policy and Planning

from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and

an AB in English from Bryn Mawr College.

“We look forward to an exciting, extended period of

leadership by Debra Edelstein. She is poised to

take the next steps to bring New England Wild

Flower Society to even greater heights of national

awareness, while realizing our conservation

mission, horticultural interests, and educational

prowess,” concluded Board of Trustees Chair Clark.

Founded in 1900, New England Wild Flower Society

is America’s oldest native plant conservation

organization, promoting the conservation of

temperate North American flora through education,

research, horticulture, habitat preservation, and

Geophysical Sciences from 1992 to 1999.

He earned his B.Sc. and Ph.D. in botany at the

University of Reading, United Kingdom. He is a

Fellow of the Royal Society, a Foreign Associate of

the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, a Foreign

Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

and a member of the German Academy Leopoldina

and member of the Botanical Society of America. He

was a Senior Mellon Fellow of the Smithsonian

Institution and serves on the board of the

Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Crane also serves on the boards of the Global Crop

Diversity Trust based at the United Nations Food

and Agriculture Organization in Rome, and the

Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, which

facilitates land conservation in the Chicago area

and the low country of South Carolina.

He was knighted in the United Kingdom in 2004 for

services to horticulture and conservation. His many

awards include the Schuchert Award of the

Paleontological Society, the Henry Allan Gleason

Award of the New York Botanical Garden, the

Hutchinson Medal of Chicago Botanical Garden

and the Botanical Society of America Centennial

Award.

Crane’s appointment at Yale as the Carl W.

Knobloch, Jr. Dean is effective September 1, 2009.

He succeeds James Gustave Speth, who Levin

said has provided “superb leadership” since 1999.

“The new dean will inherit a school that has seen

remarkable growth in faculty, student applications,

and the availability of scholarship assistance over

the past 10 years,” Levin said. “Dean Speth, a

passionate advocate for a greener Yale, has played

a key role in increasing national and international

awareness of climate issues.”

61

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Carnegie’s Arthur Grossman

Receives Gilbert Morgan Smith

Medal

Stanford, CA—The National Academy of Sciences

has awarded Arthur Grossman, of the Carnegie

Institution’s Department of Plant Biology, the 2009

Gilbert Morgan Smith Medal “in recognition of

excellence in published research on marine or

freshwater algae.” The award was established

through the Helen P. Smith Fund.

Grossman is a pioneer in studying a broad range

of topics about Chlamydomonas, a tiny green alga

affectionately called Chlamy, which is present in

soil and freshwater. He also brought Chlamy into

the age of genomics by leading the project that

helped to define its full genome sequence and then

exploiting the genomic information. Chlamy

performs photosynthesis like plants, but it diverged

evolutionarily from flowering land plants about 1

billion years ago and therefore contains many

characteristics common to all plants, as well as

characteristics associated with animals but not

with flowering plants. Grossman’s research is

important both for understanding basic

mechanisms in photosynthetic organisms as well

as their evolution. He has investigated metabolic

processes and the acclimation of algae and

cyanobacteria (formerly called blue-green algae) to

changing environmental conditions, the diversity of

genomes of photosynthetic microbes in hot spring

mats and the physiological functions encoded by

those genomes, and energy use by photosynthetic

microbes in the marine environment. In addition, he

is part of a team working with new methods to study

gene expression or transcriptomics in alga.

“Art is recognized worldwide as a major figure

shaping our understanding of algae,” remarked

Carnegie president Richard A. Meserve. “We

congratulate him on this honor.”

Grossman has been a staff scientist at Carnegie

since 1982 and professor by courtesy at Stanford

University. He received his B.S. from Brooklyn

College, and his Ph.D. from Indiana University.

Grossman received the prestigious 2002 Darbaker

Prize for his microalgae work from the Botanical

Society of America. He has served on numerous

panels and editorial boards, including Current

Genetics, Eukaryotic Cell, Molecular Plant, Plant

Physiology and the Annual Review of Genetics. He

regularly reviews papers for journals such as

Science, Nature and PNAS.

Nagib Nassar , BSA Member,

Celebrates 50 Years Teaching And

Research

My love of plants goes back to very early life at the

age of 12 onwards, planting shrubs in our house

garden, accompanying their growth and thinking in

them every moment. They were my enjoyment, my

hobby and my entertainment. At the University I

began to examine flowers and learn about their

systematics. This opened for me the door to a very

exciting world of botany in which I live up to this date.

For my Ph.D. study I applied cytogenetic data to the

taxonomy of Chenopodiaceae in what is known

now as cytotaxonomy.

My fifty years teaching were divided into 16 years

with Cairo University from 1958 to 1974 and 34

years with the University of Brasilia. This multi-

cultural experience exposed me to a broad range of

learning styles and allowed me to acquire a number

of different teaching methods. At Cairo University I

taught horticulture and conservation of plant genetic

resources. At Brasilia I taught plant breeding, organic

evolution, evolution of cultivated plants, basic

cytogenetics, cytogenetics methods and

techniques, economic botany, plant breeding of

perennial crops, and botany of Cassava to both

graduate and post-graduate students. I have taught

several of these courses at the federal universities

of Goias, Vicosa, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasilia, Feira

Santana, and Sao Paulo in Brazil, the Pan American

center in Costa Rica, and Bern University in

Switzerland.

advocacy. The Society’s vision is a future where

vigorous native plant populations live in healthy,

balanced, natural ecosystems-protected, enjoyed,

and beneficial to all life.

Professor Nassar with students at the University

of Brasilia

62

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Conserving wild cassava, Manihot species native

to Brazil and Mexico. was the most fascinating work

in my career, which began 35 years ago. My

knowledge of the botany of this group enabled me

collect and conserve them and manipulate them for

crop improvement. I emphasize to my students that

knowing the botany of a certain crop is the principal

step towards improving it. You cannot successfully

use a wild species in an improvement program or

breed it with cultivated forms without knowing in

what habitat it grows. This provides clues to

important characteristics that may be incorporated

into the cultivar. Breeders must also understand the

reproductive system of his crop to choose adequate

methods of breeding.

-Nagib Nassar, Departamento de Genética e

Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas,

Universidade de Brasília, Campus Universitário,

Darcy Ribeiro, Asa Norte, 70910–900, Brasília –DF,

Brazil

Phone: (+55.61) 307.20.22; Fax:(+55.61) 272.00.03;

Email:

nagnassah@rudah.com.br

Dr. Susan Pell, Brooklyn Botanic

Garden Scientist, Returns from

Successful Plant Research

Expedition in Papua New Guinea.

Brooklyn, New York – March 10, 2009. Dr. Susan

Pell, Brooklyn Botanic Garden Scientist, and

member of the Botanical Society of America, recently

completed the first botanical survey of the three

main islands of Papua New Guinea’s Louisiade

Archipelago in 50 years.

Throughout the five-week adventure, Dr. Pell, the

Garden’s plant systematist and laboratory manager,

worked with BBG’s web team to keep a blog detailing

her team’s challenging work climbing mountains,

fording rivers, and sleeping on a small boat in order

to make over 800 plant collections that are sure to

greatly expand the existing knowledge of the Milne

Bay flora.

Their exploration and study of the three main islands

of the Louisiade Archipelago, Misima, Rossel, and

Sudest, is key: These islands are home to many

species found nowhere else in the world. The work

done in Papua New Guinea by Dr. Pell and her team

include the collection of a plant that has been

collected only twice before – and never described –

My teaching experience has been very rewarding. It

is from my experience with teaching that I

have gained my greatest strength. Teaching for me

was like composing a piece of music, and for years

and years I had the aspirations of being admired by

my students the same way they admire their idols

of musicians and artists. I always try to create a

strong friendship with my students from the moment

they joined my class up to their graduation.

In 1975, I began my first mission to collect wild

Manihot species in Brazil on behalf of IITA

(International Institute of Tropical Agriculture). I was

at that time a visiting scientist sponsored by the

Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Relations stationed at

the University of Sao Paulo. The financial support of

IITA was so small that did not permit me to hire any

assistant to accompany me in my collection trips. By

the end of four months trips I was able to collect

seeds of more than 20 wild species native to 8

Brazilian states.

Collecting wild species for IITA encouraged me to

plant and propagate a living collection at the

Universidade de Brasilia. My goal was not only to

propagate and conserve them but to use them for

crop improvement. Five years later, I was able to

provide IITA with hybrid seed that gave rise to

cultivars now planted on about 4 million hectares in

Nigeria making it the top-ranking producer of

cassava all over the world. “Your breeding approach

shows the benefits of preserving biodiversity … for

enhancing casava germplasm…[and]new

methods for the propagation of this crop…” says

Rodomiro Ortiz , director of IITA.

See

http://www.geneconserve.pro.br/iita2.gif

a n d

h t t p : / / w w w . g e n e c o n s e r v e . p r o . b r /

decades_of_cassava.pdf

The success of my work on wild Manihot in the

decade 1970s encouraged the International Board

of Genetic resources-IBPGR to delegate me for a

mission of 3 months collecting wild Manihot native

to Mexico. Since the1980s I continued working

on cassava and for the last decade I have

concentrated on embryology of this group . This led

me to the most important discovery ever made in

these species, the discovery of apomixis and

transference of its genes to cultivated forms,

producing the first apomictic cultivars of this crop.

This shows how much botany could serve breeding

programs and botanists.

Most recently I was involved in developing cassava

hybrids that are rich in protein. The first such hybrid

was bred by me early in the 1980s. We can now

release hybrids that are very productive and contain

high protein and essential amino acids.

63

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

giving the explorers a rare glimpse into some of the

world’s most exciting flora.

The five-week expedition was more than five years

in the planning. Dr. Pell and her five-member team,

including scientists from New York Botanical

Garden, Botanical Research Institute of Teas, and

Conservation International, set out in early January

to work with local naturalists to survey the flora of the

area, compile a conservation assessment, and

identify members of the cashew and frankincense

plant families. Data from the project will become an

integral part of an online tree flora database of New

Guinea, and new plant specimens will be housed

in the PNG National Herbarium, BBG’s herbarium,

and other herbaria in Papua New Guinea and

stateside.

Throughout her trip, Dr. Pell’s blog, Expedition:

Papua New Guinea, provided a gripping, frontline

reality show imbued with all the challenges and

curiosities that only a scientist can capture and

share. And Dr. Pell’s stunning photos offer a

window into a part of the world few have ever seen,

especially in such a personal way.

Dr. Pell was selected as a Wings WorldQuest

Foundation explorer for this expedition. The

foundation is the leading resource and advocate for

women explorers worldwide. Dr. Pell will be

available for interview to recount her incredible field

research experience and the making of her web

diary:

bbg.org/blogs/expedition

.

Contact: Leeann Lavin,

LeeannLavin@bbg.org

or

718-623-7289 to arrange interviews.

GRANTS FOR ORNAMENTAL

HORTICULTURE

The Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust invites

applications for grants up to $20,000 for education

and research in ornamental horticulture. Not-for-

profit botanical gardens, arboreta, and other tax-

exempt organizations are eligible.

The deadline for applications is August 15, 2009.

For current guidelines, send a brief message that

indicates a potential project and identifies your

organizational affiliation to: Thomas F. Daniel, Grants

Director, SSHT, Dept. of Botany, California Academy

of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Dr., Golden Gate

Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA email:

tdaniel@calacademy.org

Award Opportunities

Symposia, Conferences,

Meetings

International Orchid Symposium

January 12-15, 2010

Taichung, Taiwan

Welcome to the first International Orchid

Symposium, organized by the International Society

for Horticultural Science (ISHS) Orchid Working

Group. Academics, scientists, and industry leaders

are invited to participate in the sharing of research-

based information on orchids.

This meeting will be held January 12-15, 2010 in

Taichung, Taiwan. Taiwan is home to large-scale

commercial production of orchids, particularly

phalaenopsis, as well as numerous scientists

focused on orchid research.

The primary topics of the meeting are:

1. Orchid anatomy and morphology

2. Orchid ecology

3. Orchid genetics and breeding

4. Orchid micropropagation and seed

germination

5. Orchid production (including pest and virus

control)

6. Orchid postharvest and marketing

This symposium will be held at the National Museum

of Natural Science (NMNS,

http://www.nmns.edu.tw

)

in the downtown of Taichung City (the west-central

region of Taiwan). There are two lecture theaters

(each with a capacity of 200 people) with modern

facilities for holding the international symposium.

International symposium participants are

encouraged to arrive into Taoyuan International

Airport (formerly known as Chiang Kai-shek

International, or C.K.S. airport.), which is located

outside of Taipei. From Taoyuan International

Airport, it takes about 2 hours to reach Taichung City

by bus.

For more information see:

http://www.hrt.msu.edu/ios/

64

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

VII International Congress of Systematic and Evolutionary Biology,

ICSEB 7

“Extending the Darwinian Panorama”

Veracruz, Mexico

5-10 July 2009

for more informaiton see:

http://www.botanik.univie.ac.at/ICSEB7/

56

th

Annual Systematics Symposium Missouri Botanical Garden

“Angiosperm phylogeny: not just trees, but insects, fungi, and much more”

9-11 October 2009 With support from the National Science Foundation

REGISTRATION

SATURDAY-SUNDAY, October 10-11

Kevin Boyce: Ecophysiology of early angiosperm evolution

Bryan Danforth: Bee phylogeny and angiosperm diversification

Peter Endress: Floral morphology and eudicots

Else-Marie Friis: Early angiosperm fossils

Thomas Givnish: Whole genomes and major branchings in monocots

Conrad Labandeira: Paleohistory of plant/insect interactions

Paula Rudall: Monocot floral development and diversification

Vincent Savolainen: Phylogeny of the monocots

Christopher Schardl: Endophytes and plants, especially Poaceae

Doug Soltis: Broad-leaved angiosperm diversification

SPACE LIMITS REGISTRATION TO 400; PLEASE REGISTER EARLYRegistration must be accompanied

by an $85.00 registration fee, which also covers the cost of refreshments at the Friday mixer and lunch

and dinner on Saturday. Information on local hotels and motels will be available to registrants. No refunds

will be granted after 24 September. There is no guarantee of food being available if you register after 30

September. For electronic payment, see future updates on symposium webpage.

I plan to attend the Systematics Symposium. Enclosed is my $85.00 registration fee. Please make checks

payable to “Missouri Botanical Garden” I enclose my registration fee of $85.00 _____

I request vegetarian meals: _____

My name and professional address: ________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Phone:___________________ Fax:_________________ e-mail address:_____________

Please indicate if you are a)a graduate student _______ or b)an undergraduate student _______

Mail registration form to: Systematics Symposium Missouri Botanical Garden P.O. Box 299 St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299 For further information, contact: P. Mick Richardson Email:

mick.richardson@mobot.org

Tel: 314 577 5176 Fax: 314 577 0820

65

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Other News

Lecture Celebrates Monumental

Anniversaries of Two

Botanical Gardens

“Kew, Missouri Botanical Garden and

the Global Botanical Network –

Powerhouse for a Better Future,”

Professor Stephen D. Hopper

Director of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

WHAT: “Kew, Missouri Botanical Garden and the

Global Botanical Network – Powerhouse for a Better

Future,” a lecture by Professor Stephen D. Hopper,

director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

WHEN: Monday, June 1, 2 p.m.

WHERE: Monsanto Center, 4500 Shaw Blvd., south

St. Louis (two block west of the Missouri Botanical

Garden at the Shaw-Vandeventer intersection)

NFO:

www.mobot.org;

(314) 577-9400, 1 (800)

642-8842 toll free

As the Missouri Botanical Garden celebrates 150

years of botanical research, science education and

horticultural display, the Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew, near London is celebrating its 250th

anniversary. Join Kew director and plant conservation

biologist Professor Stephen D. Hopper for a lecture,

“Kew, Missouri Botanical Garden and the Global

Botanical Network – Powerhouse for a Better Future,”

on Monday, June 1 at 2 p.m. at the Missouri Botanical

Garden’s Monsanto Center, 4500 Shaw Blvd. The

event is free and open to the public.

Hopper is best known for pioneering research

leading to positive conservation outcomes in

southwest Australia (one of the few temperate-zone

global biodiversity hotspots). He collaborated on

the descriptions of 300 new plant taxa and has

authored over 200 scientific publications. Hopper

has explored Australian deserts since 1980, and

conducted research in South Africa and the USA.

As Foundation Professor of Plant Conservation

Biology at the University of Western Australia from

2004 to 2006, he developed new theories on the

evolution and conservation of biodiversity on the

world’s oldest landscapes, and led the

establishment of new degrees in conservation

biology.

The Missouri Botanical Garden and the Royal

Botanic Gardens, Kew share a unique connection.

From 1849 to 1851, Missouri Botanical Garden

founder Henry Shaw traveled extensively in the

United States and Europe. During one of his trips to

England, Shaw was inspired to give the people of

St. Louis a garden like the great gardens and

estates of Europe. Shaw was encouraged to build

a garden involved with scientific work like the great

botanical institutions of Europe. With the assistance

of Harvard botanist Asa Gray and Sir William Hooker,

director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew at the

time, Shaw was persuaded to include a herbarium

(collection of botanical specimens) and a library.

A Garden to Die For: Wicked Plants

at Brooklyn Botanic Garden

The awesome power of plants is on display this

summer with Wicked Plants at Brooklyn Botanic

Garden, from May 31 through September 6, 2009.

Although plants have nourished and succored,

seduced and delighted humans throughout history,

this summer, BBG highlights a rogue’s gallery of

the most nefarious, troublesome, and even

potentially deadly members of the plant kingdom.

Wicked Plants at Brooklyn Botanic Garden

introduces visitors to over 50 plants in the Garden

whose capacity to injure, poison, or perhaps just

irritate humans is a powerful reminder to tread

lightly in the plant world.

Inspired by the upcoming release of author Amy

Stewart’s Wicked Plants: A Book of Botanical

Atrocities, Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s summer

interpretive highlight gives visitors a closer look at

the sometimes problematic relationship between

people and plants. In ten areas throughout the

Garden, on-site text and the Garden’s first-ever

audio tour, featuring its science and horticulture

staff, share facts, advice, and tales of close

encounters with wicked plants. Visitors will learn

about such botanical menaces as monkshood

(Aconitum sp.), a member of the buttercup family

used to tip spears for killing prey—and people; ricin

(Ricinus communis), an extract of the castor bean

that was used to poison a Bulgarian dissident in the

1970s; and the jumping cactus (Cylindropuntia

fulgida), which terrorizes hikers by seeming to leap

onto clothing or exposed skin.

Yet, for every “villainous” aspect of a particular plant,

BBG’s interpretation will shed light on plants’

redemptive characteristics. The foxglove (Digitalis

species), for example, tellingly also called “witch’s

gloves” or “dead man’s bells,” causes violent

reactions when ingested; but the plant is also used

to make digitalis, which helps regulate the human

heart—a boon to victims of cardiac distress.

66

Plant Science Bulletin 55(2) 2009

Reports and Reviews

Botany at Eastern Illinois

University

Marissa C. Jernegan Grant, Nancy E. Coutant,

and Janice M. Coons

Biological Sciences Department, Eastern Illinois

University, Charleston, IL 61920

ABSTRACT

Eastern Illinois University was established in 1899,

and from its beginning the importance of the

botanical sciences was recognized. Two terms of

botany were required for the four year program. Dr.

Otis W. Caldwell, a botanist, was one of the original

faculty members. He taught all of the biology courses

and initiated the acquisition of a greenhouse.

Caldwell was the first in a series of talented and

dedicated botany professors including Edgar N.

Transeau, Ernest L. Stover, Hiram F. Thut and John

E. Ebinger. These and many other professors

incorporated a field component into almost all

classes. This dedication to the study of plants in

their natural habitat led to one of the finest programs

in the nation for training field botanists. By 1923, a

formal Botany Department was established and in

the late 1960’s EIU began awarding a M.S. in

Botany. In the 60’s, the department greatly expanded

with 15 faculty hires and over 40 different

undergraduate and graduate courses were offered

with 95% having a lab component. The excellence

of the program was recognized in Illinois where

organizations such as the Illinois Department of

Natural Resources and the Illinois Natural History

Survey relied on graduates from the EIU Botany

Department for their field botanists. In 1992, the

American Phytopathological Society recognized the

department for its contribution to plant pathology.

Between 1913 and 1993, six hundred and nine

students graduated with degrees in Botany, and

121 continued to receive their doctorates in botanical

fields. Although numbers of botany majors rose

during early to mid 1990’s, an administrative

decision was made in 1998 to combine the Botany

Department with the Zoology Department into a

Biological Sciences Department. Since the merger,

the B.S. in Botany was eliminated. Unfortunately,

the elimination of this Botany Department is another

example of past national trends to eliminate Botany

Departments even with exceptional reputations.

EARLY YEARS

IIn the past two decades, a trend has occured for

many colleges and universities to allow their plant

biology programs to be replaced with a pre-medical

or cellular and molecular biology curriculum

(Salopek, 1996). Occasionally, independent

departments focusing separately on botany and

zoology are merged, thus squeezing botany classes

into the general biology degree where often they

lose their individual niche. According to the Chicago

Tribune, a misguided emphasis is placed on “big

science,” keeping researchers in the lab and

students in the classroom instead of exploring the

outdoors and discovering what field botany offers

(Salopek, 1996). Eastern Illinois University

dissolved its nationally recognized Botany

Department in 1998. The program had a very strong

organismal focus. With more and more botany

programs disappearing or condensing, we were

inspired by the Historical Section at the 2007

Botanical Society of America meeting to report on

the history of the once renowned Botany Department

at Eastern Illinois University.

Eastern Illinois Normal School was established in

September of 1899. The City of Charleston had

donated “Bishop’s Woods,” a 40-acre tract, to the

cause of the Normal School. This area was partially

covered by a grove of trees. The north half of this tract

of land, from pictures, was quite well wooded, but

the south half was cleared, presumably for farming

purposes. In this grove was where the one building

(Old Main) for the Normal School was built, along

with its power house some 150 feet directly south.

The two were connected by a heating tunnel. As a

training school for teachers, it offered one, two,

three, and four year teaching diplomas. Botany

classes were one of the first required course

offerings, and interestingly enough, zoology was an

elective. During the tenure of Eastern’s first

president, Mr. Livingston C. Lord, a Biological

Sciences Department was established. The Botany

and Zoology Departments became separate

entities in the early 1920’s. Of the eighteen original

faculty members initially hired by President Lord,

Dr. Otis W. Caldwell, a botanist, was the only faculty

member to hold a doctorate degree (Coutant and

Crofutt, 1996; Thut, 1967). Caldwell taught all of the

biology classes along with coaching the football

team for three years. He was the entire department.