BULLETIN

SPRING 2009

VOLUME 55

NUMBER 1

2@2

PLANT SCIENCE

ISSN 0032-0919

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Leading Scientists

and

Educators

since 1893

Welcome to 2009 – The Year of Science in the United States...............................................................2

News from the Society

Botany & Mycology 2009....................................................................................................2

Membership News.................................................................................................................4

Vision and Change in Biology Undergraduate Education: A View for the 21ST Century.....4

BSA Science Education News and Notes..............................................................................6

Editor’s Choice......................................................................................................................8

Applications Solicited, Editor, Plant Science Bulletin, 2010 – 2014....................................9

In Memoriam:

Dr. Steven Clemants 1954-2008.........................................................................................10

Personalia

Warren Abrahamson Selected Fellow of the American Association for the

Advancement of Science.......................................................................................11

Randy Moore Wins National Evolution Education Award.................................................12

Dr. Gregory Mueller named Vice President, Science and Academic Programs at the

Chicago Botanical Garden....................................................................................12

Peter Raven Receives Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Council

for Science and the Environment..........................................................................13

Bringing Modern Roots to a Traditional Collection After 10 years in New York City,

Ken Cameron was Ready for a Change................................................................14

Courses/Workshops

National Tropical Botanical Garden Fellowship for College Biology Professors...............15

.

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings

13th Natural History Conference Celebrating 25 years of Annual Conferences at the

Gerace Research Center, Bahamas......................................................................16

ICPHB 2009 International Conference on Polyploidy, Hybridization and Biodiversity....16

Positions Available

Director, Steinberg Museum of Natural History.................................................................17

Other News

Missouri Botanical Garden Celebrates 150TH Anniversary in 2009.................................18

JSTOR Expands Free Access in Developing Nations.........................................................19

National Tropical Botanical Garden earns LEED Gold.......................................................19

Reports and Reviews

Growing SEEDS of Sustainability at UBC: Social, Ecological, Economic Development Studies(SEEDS)

Program at the University of British Columbia..................................................................20

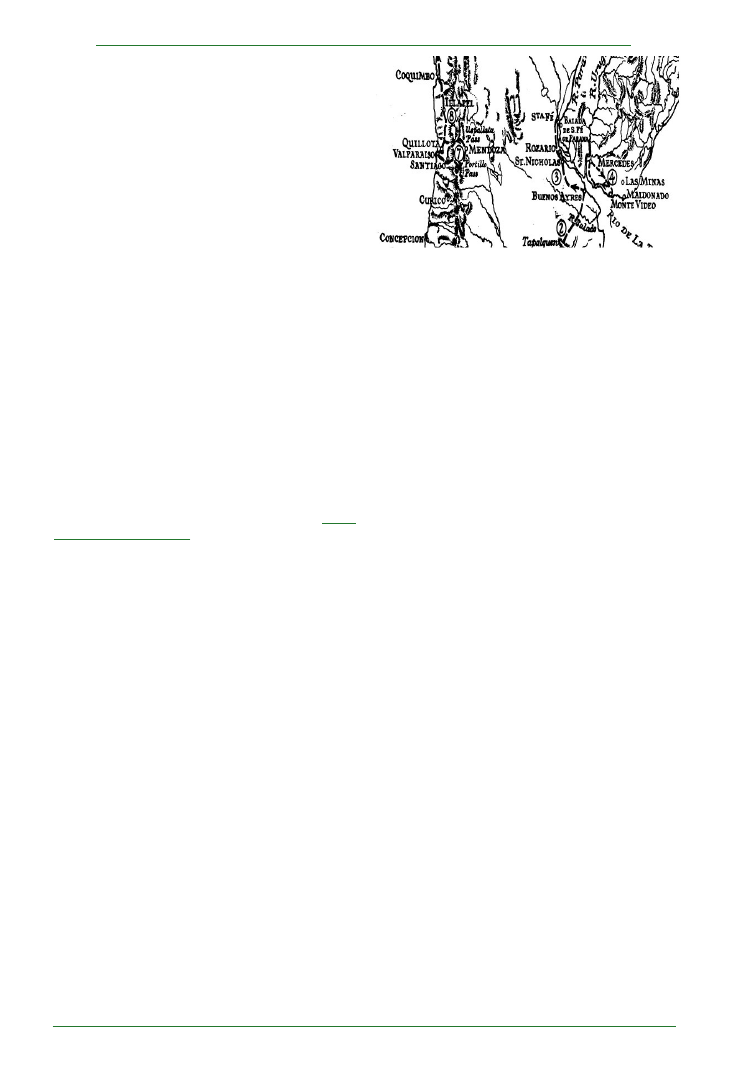

Darwin in the Year of Science, 2009....................................................................................................24

Books Reviewed...................................................................................................................................28

Books Received....................................................................................................................................46

Botany and Mycology, 2009...............................................................................................................48

2

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Botanical Society of America

Business Office

P.O. Box 299

St. Louis, MO 63166-0299

E-mail: bsa-manager@botany.org

Address Editorial Matters (only) to:

Marshall D. Sundberg, Editor

Dept. Biol. Sci., Emporia State Univ.

1200 Commercial St.

Emporia, KS 66801-5057

Phone 620-341-5605

E-mail: psb@botany.org

ISSN 0032-0919

Published quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 4475 Castleman Avenue, St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299. The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of

the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Periodical postage paid at St. Louis, MO and additional

mailing office.

News from the Society

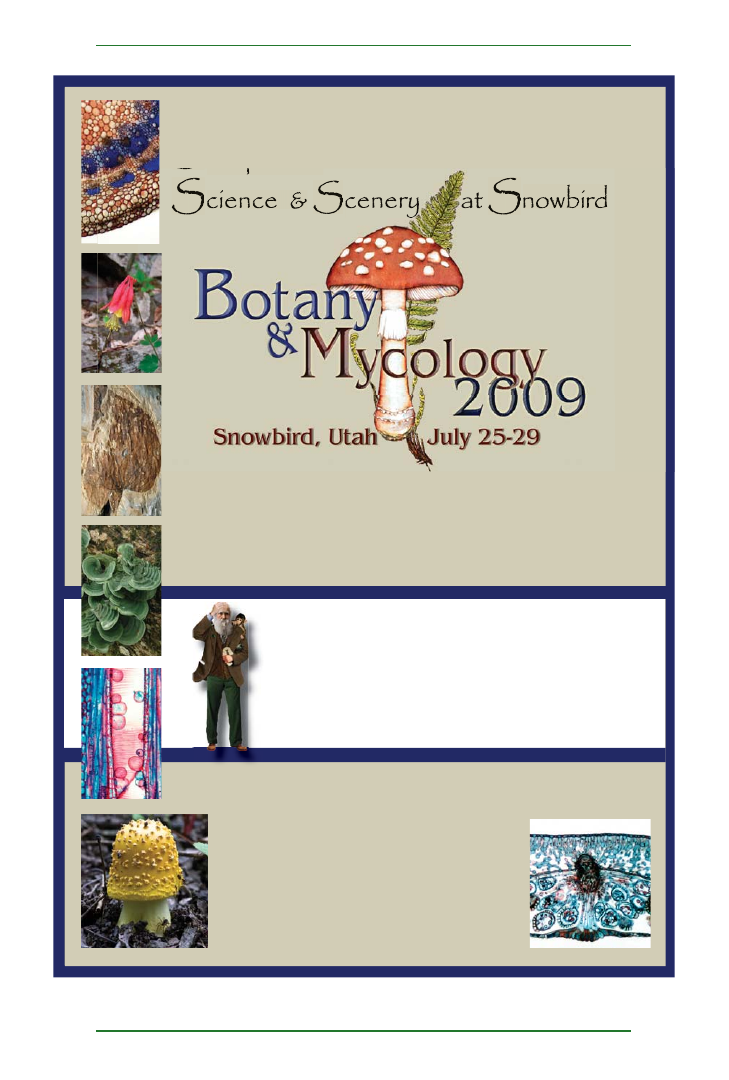

Botany & Mycology 2009

Dear Members of the Botanical Community,

Plans for Botany & Mycology 2009 are well under

way!

Botany & Mycology 2009 is the one conference you

can’t afford to miss this summer!

The days are growing longer, and although most of

us are in a deep freeze, we are all starting to think

about this coming summer and our annual

conference. We are very excited about the location,

the exploration and the scientific research that will

be shared with this global community of scientists

and scholars. If you have never attended our

annual joint conference, this is the year!

This year we will be meeting with a new partner, the

Mycological Society of America, as well as our

traditional partners: the American Fern Society, the

American Bryological and Lichenological Society,

the America Society of Plant Taxonomists, and the

Botanical Society of America.

The conference will include some events that have

taken place at past meetings such as field trips,

workshops, discussion sessions, social events

and plenty of time for networking and catching up

with old friends—all in the beautiful setting of the

Wasatch Mountains at the Snowbird Conference

Center in Snowbird, Utah.

In light of the current global economic situation, we

have been working hard to make this conference

affordable to all and especially to all students.

We’ve kept registration rates as low as possible for

2009; in fact, we have rolled back the early

registration rates to the Botany 2006 level! We have

contracted great room rates for the conference,

including condo units with full kitchens that can

Welcome to 2009 – The Year of

Science in the United States.

The BSA contribution to the celebration already has

begun with the special first issue of 2009 of the

American Journal of Botany dedicated to the

botanical works of Darwin. Plant Science Bulletin

adds to this effort with an article on Darwin’s science,

presented as three case studies that can be

incorporated into teaching introductory-level

students. Darwin is an icon for evolution, and rightly

so, but his contributions to botany and the scientific

way of knowing are too often overlooked.

Also featured in this issue is an article based on one

of the Botany 2008 workshops last year in Vancouver.

The SEEDS program (Social, Ecological, Economic

Development Studies) at UBC is a model for

interdisciplinary collaboration to promote

sustainability on university campuses. “Green” is

the rage on many campuses today, but examples of

bottom-up commitment and innovation are rare.

The authors provide a snapshot of what has become

a very popular and productive program on their

campus.

Finally, you may have noticed a slight change in

format with this issue of PSB. For the past nine

years, contributed (or solicited) articles have had

prominent placement at the front of each issue with

the intention of luring readers into perusing the

issue. Whether or not this was a successful strategy

is inconclusive, but it has not stimulated increased

article contributions. One reason must be that

articles generally are not reviewed (on occasion

they have been) and for many of us only peer-

reviewed papers “count” as scholarship. We are

considering some changes in PSB to include peer-

reviewed

Reports and Reviews,

which will follow the

informational

News from the Society.

Let us know

what you think.

– the Editor.

3

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Editorial Committee for Volume 55

Joanne M. Sharpe (2009)

Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens

P.O. Box 234

Boothbay, ME 04537

joannesharpe@email.com

Nina L. Baghai-Riding (2010)

Division of Biological and

Physical Sciences

Delta State University

Cleveland, MS 38677

nbaghai@deltastate.edu

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

Jenny Archibald (2011)

Department of Ecology

and Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick (2012)

Department of Biology

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler (2013)

Department of Botany

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

schusse@muohio.edu

sleep up to six, and we have negotiated special

dining options each day for all attendees to help

keep costs of attending the conference affordable.

At Snowbird there are seven different restaurants

ranging from “get-it-quick pizza” to full-service fine

dining options opening early and staying open late!

There is also a General Store on site if you wish to

eat in your room…or stop and stock up before you

come up the Mountain. There will be several ticketed-

event lunches as well as kiosks to grab a quick

sandwich and sit out in the sunshine between

scientific presentations.

Again this year there is special pricing for students

to attend society banquets and other social events—

so spread the word and bring your students with

you! Students can also invite their non-member

friends to register and come along.

Plan now to arrive early to take advantage of the

variety of field trips being offered. Each offering is

designed to show off the botany of the Salt Lake City

area. Highlights include a trip to the Stanley Welsh

Herbarium at Brigham Young University; a visit to

the Milford Flat Restoration Project, an area being

restored after a devastating wildfire; or join with our

mycological friends on their annual foray!

Sunday’s schedule will include FREE workshops

and more field trips. Be sure to attend the Plenary

Lecture with noted ethnobotanist Nancy Turner on

Sunday evening. Following the lecture, come to the

All Society Mixer where you can connect with your

friends and colleagues as the conference officially

begins.

Monday morning kicks off a week of Scientific

Presentations including a full line-up of compelling

symposia. Times and information can be found on

the conference website:

www.2009.botanyconference.org

Something new this year—poster presentations

will take place in the Exhibit Hall both Monday and

Tuesday late afternoons. This time has been

selected to be sure attendees and presenters have

enough time to view all the posters and not feel

rushed! Posters, Mixers and Exhibits…it doesn’t get

any better!

Monday evening attendees can choose from the

Paleobotanical Section Banquet or a Bar-B-Que on

the Mountain. Everyone is invited to catch up with

friends and colleagues and dance to the music of

Hearts Gone Wild! (Again, we offer special pricing

for students)

On Tuesday evening, plan to attend the ASPT

Banquet, and on Wednesday, come to the All Society

Banquet & Auction for dinner, award presentations

and joint auction fun supporting programs of the

MSA and ASPT.

With its relevant and groundbreaking scientific

presentations, the incredible field trip opportunities,

all the networking and mingling, Botany & Mycology

2009 is the one conference you can’t afford to miss

this summer!

Submit your abstracts now.

.

Conference Registration and Housing are also

open and ready for you! All available at

www.2009.botanyconference.org.

Abstract Submissions:

w w w . 2 0 0 9 . b o t a n y c o n f e r e n c e . o r g / e n g i n e /

login.php?next=abstract

Registration:

https://crm.botany.org/engine/

login.php?next=registration

Housing Information:

w w w . 2 0 0 9 . b o t a n y c o n f e r e n c e . o r g / L o d g i n g /

index.php

4

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

We look forward to seeing you at Snowbird!

The Conference Team

Botanical Society of America

www.2009.botanyconference.org

P.S. Remember the beautiful mountain setting for

this meeting and bring your family. Camp Snowbird

will be open for your kids to enjoy. For the

adventurous—daily wildflower hikes up the

Mountain, the great climbing wall, the historical city

of Salt Lake—lots to do and see!

Membership News.

January 1st kicked off a new year for Botanical

Society of America and for American Journal of

Botany subscriptions. There has been so much to

get excited about this year at the BSA. The Society

is growing and evolving with record membership

achieved in 2008. We continue to remain THE home

for ALL plant scientists, educators, students and

plant enthusiasts. New to the Society is AJB Advance

Access, which allows us to post your finalized

articles in advance of print, providing everyone with

faster access to the latest research and potentially

higher citation rates. We are also very excited about

the enthusiastic response to the American Journal

of Botany’s special Darwin issue, published in

January 2009. Individual issues of the special issue

are available for purchase at the special member

price of $50. Please visit

https://

crm.botany.org/bsamisc/specialajb.php

or

contact the BSA office in order to purchase an issue.

If you have not done so, please renew your

membership in the Society today. Please go to

https://crm.botany.org/joinbsa/. If you have

any questions regarding your memberhip, please

contact me at

hcacanindin@botany.org

.

This year, we again offer you the opportunity to

provide $10 student gift memberships to the current

crop of potential botanists gracing your classes,

offices and labs through the online membership

renewal system. We understand that the best way

to grow support for botany and the BSA is to replicate

the experience most of us shared early in our

careers, when a professor or mentor took the time

to ensure we joined the right organizations. With

just an extra click, you can add to our ranks and

introduce an aspiring plant scientist to this

supportive botanical community.

We also invite you to take advantage of the

opportunity of giving gift associate memberships to

colleagues from developing countries at the special

rate of $10. Last year we extended this “botanical

hand of friendship” to a number of botanists who

may not have had the opportunity to join the BSA.

Use this web address to renew your membership

and/or give a gift securely online in just a few

minutes.

https://crm.botany.org/joinbsa/

During the renewal process, you can volunteer to

get involved in BSA Committee work as well as sign

up to be a mentor in the BSA-led PlantingScience

program. We value your contributions in time and

effort to support Botany!

The BSA is such a wonderful community of scholars

and scientists serving the science of Botany. Please

consider renewing your membership today and

spread the word…….BSA is THE home for ALL

plant scientists! Thank you for your dedication and

loyalty to the Botanical Society of America, and for

the work you do every day. You really are part of the

“greening” of this planet.

Remember, think sunshine and mountains and

we’ll see you in Snowbird at Botany & Mycology

2009!

Vision and Change in Biology

Undergraduate Education: A View

for the 21ST Century

Scientific Societies are being asked to step forward

as leaders, and to participate in providing meaningful

change in undergraduate education by: setting new

standards for how we view the scholarship of

teaching and learning in all of our activities; holding

conferences on education; serve as stewards of

our disciplines by acting as repositories of content

knowledge, developers and stewards of educational

materials, and providers of professional

development activities for our disciplines; provide

membership for educators; and collaborate with

other societies.

In November of 2008, BSA representatives--BSA

Past-president Dr. Christopher Haufler, BSA Student

Representative James Cohen, and I (Executive

Director, Bill Dahl) - attended a meeting of biological

societies organized and hosted by the American

Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI)

with support from the National Science Foundation

(NSF) Division of Undergraduate Education (DUE)

and the Directorate of Biological Sciences (BIO).

The meeting was the second in a series to explore

how professional Scientific Societies might be

engaged as leaders in supporting needed changes

5

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

in undergraduate education as it pertains to biology.

The meeting organizers hope that this series of

meetings will give the biological community and the

community at large some insight into the changes

that need to take place, how best to effect those

changes, and how best to support evolving efforts

for change.

The premise of the organizers was that the

disciplines of biology and of science education

have undergone a revolution. The major focus of the

biological sciences – understanding life – remains

unchanged; but, breakthrough discoveries of the

second half of the 20th century have changed the

basic nature of the questions asked, while new and

emerging technologies are changing the ways key

questions are addressed.

It was noted that in undergraduate science,

technology, engineering and math (STEM)

education, new approaches and new technologies

are emerging based on evolving theories of learning.

New developments in the nature of institutions of

higher education have changed the manner in

which people pursue higher education and there is

a growing appreciation of the need to broaden

participation within the sciences by advancing the

education of all students including those from

underrepresented groups and those who will enter

careers other than those related to science. There

is also a growing realization of the necessity to fully

inform and educate all students about the wealth of

professions available to those who study the

sciences and about the way science is done.

BIO2010 was quoted to rouse interest in the need

for reform of undergraduate biological education

raising many important issues and giving

suggested approaches, mostly applied to those

students preparing for a career in biomedical

research. It could serve as a base for a broader

approach that would encompass all the sub-

disciplines within the biological sciences.

Snapshot Presentation from Societies - Sharing

Our Experience

Each of the societies present at the meeting was

asked to share their experiences contributing to

undergraduate education. I presented what the

BSA group felt were the most relevant activities in

conjunction with the discussion. They included:

Membership - getting young scientists involved in

the Society and encouraging participation/

networking at all levels with a focus on getting

people to join the BSA as a first step. It is important

to note that the BSA acknowledge student members

as an investment in the future, not an income

stream.

-

New student members - BSA opened the

opportunity for gift memberships from professors/

peers ($10) as well as reduced the cost of new

student memberships ($15 early in the year) in

2007.

-

Renewing student members rates were

reduced to $15 to coincide with the new student &

gift membership program as noted above.

-

Dramatically reduced the student costs for

all society related activities, including conference

registrations.

-

Inclusion of teachers as a membership

group, including K-12 and Community College

involvement.

Resources Student Research Profiles - sharing

the young scientist experience -

botany.org/

students_corner/profiles/

-

Undergraduate Research Awards -

rewarding those who take the time to share their

experience (new this year).

-

Materials/activities for teachers/students -

what we provide at present teaching awards, slides/

images, scientist profiles, teaching aids, job fair,

web networking, educational forum.

Outreach

-

PlantingScience, a collaborative approach

- science is as cool as we make it!

www.plantingscience.org/

Other groups presenting included: American

Association for the Advancement of Science,

American Institute for Biological Sciences, American

Physiological Society, American Society for

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, American Society

for Cell Biology, American Society for Microbiology,

American Society for Plant Biologists, Biophysical

Society, Botanical Society of America, Ecological

Society of America, Genetics Society of America,

NAS/NRC, Society for Integrative and Comparative

Biology, Society for Neuroscience, Society for the

Study of Evolution, and the National Association of

Biology Teachers.

Actions & Commitments Moving Forward

Recognizing the wealth of expertise and diversity of

experience represented amongst the attendees,

organizers structured the meeting into discussions

orchestrated to generate ideas designed to shape

individual society and the collective biological

community agendas for action. The core questions

6

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

being:

(1) What are biological sciences professional

societies currently doing to foster change in

undergraduate biological sciences education?

(2) What else can biological sciences professional

societies do to foster change in undergraduate

biological sciences education?

Meeting attendees were broken into discussion

groups and asked to review the program in

conjunction with a series of background questions

and in light of the various activities other participants

had shared with the group. The first group meeting

was designed to provide exposure to as broad a

grouping as possible, mixing up attendees in a

manner that separated the individual society

representatives. The second was by sphere of

responsibility in society - Presidents, Board

Members, Executive Directors and Senior Staff and

Colleagues. The charge was to explore possible

“best ideas” for collective action by the community

of biological sciences societies. The “best ideas”

were required to be a specific strategy that could be

implemented. Strategies were to involve all units of

professional societies, including governance,

programs, meetings, communications, and

journals and publications.We then regrouped in

our specific organizations to develop plans specific

to our Society to share with the meeting.

As you may be aware, the BSA is undergoing a

number of activities that coincide well with the call

for support - specifically our bylaws review (which

passed) and the BSA strategic planning process

(still underway). Given education is key component

in our mission and appears to be one of the planks

in our strategic plan, we were pleased to take part

in the discussions. Chris Haufler presented the

BSA action plan to the group. He articulated our

need to complete our internal strategic planning

process before providing an in-depth response.

With this complete, he ensured the meeting the BSA

would move forward in requesting BSA members to

engage in a solution, with our initial response being

to:

Identify the core knowledge and concepts in

Botany/Plant Biology

-Networking to establish a common vision and

understanding of the core knowledge and concepts

one needs to have when entering and leaving an

undergraduate biology program.

-Across sections within the BSA (topical

disciplines)

-Across ALL Plant Societies

Compile the available resources required to meet

the agreed core knowledge and concepts in

Botany/Plant Biology and share these with the

broader biology education and learning

community

- Solicit & Network amongst BSA Sections and

Members, asking for the sharing of our best

resources covering the agreed core knowledge

and concepts in Botany/Plant Biology

-Evaluate and review submitted resources

(stamp of approval)

-Link with textbooks/learning materials

-Integrate with other biological/science

societies

As your representatives, we were aware of the depth

of the commitment and the reality that, as a Society,

our true resources are you, the BSA members and

the materials you have collected and designed over

the years, be it through teaching, learning or research

activities. With that in mind, central to our participation

moving forward, our request to you is to engage in

helping the Society to deliver on our stated objectives.

Please consider this a pre-emptive “Call to Action”,

asking members to participate through providing

the needed time and resources to complete the

task. We will make more information available as

we conclude the strategic planning process on the

BSA web site at

botany.org

.

It is likely AAAS/NSF will call for a broader meeting

of biological societies sometime in the coming year

as they move to engage the broad spectrum of

Scientific Societies in the challenge to upgrade the

undergraduate biology as never before.

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a

quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts

and the broader education scene. We invite you to

submit news items or ideas for future features.

Contact: Claire Hemingway, BSA Education

Director, at

chemingway@botany.org

or Marshall

Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org

.

Call for Education Workshops at Botany &

Mycology 2009 — submit by Feb. 15

Have you hit on an effective way of providing students

in your classroom or lab section an authentic science

experience? Do you have career development

strategies you would like to share? Are you engaged

7

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

.

in an innovative outreach effort? Your colleagues

would like to hear about new ideas for teaching,

outreach, or training activities. What better place to

share with them than Snowbird, Utah. Join us on

Sunday, July 26. Workshops are typically hands-on

sessions; they are free to participants and can be

two-hour, half-day or full-day in length. Submit your

workshop abstract online by February 15.

http://

www.2009.botanyconference.org/2009Calls/

2009ls_Workshops.php

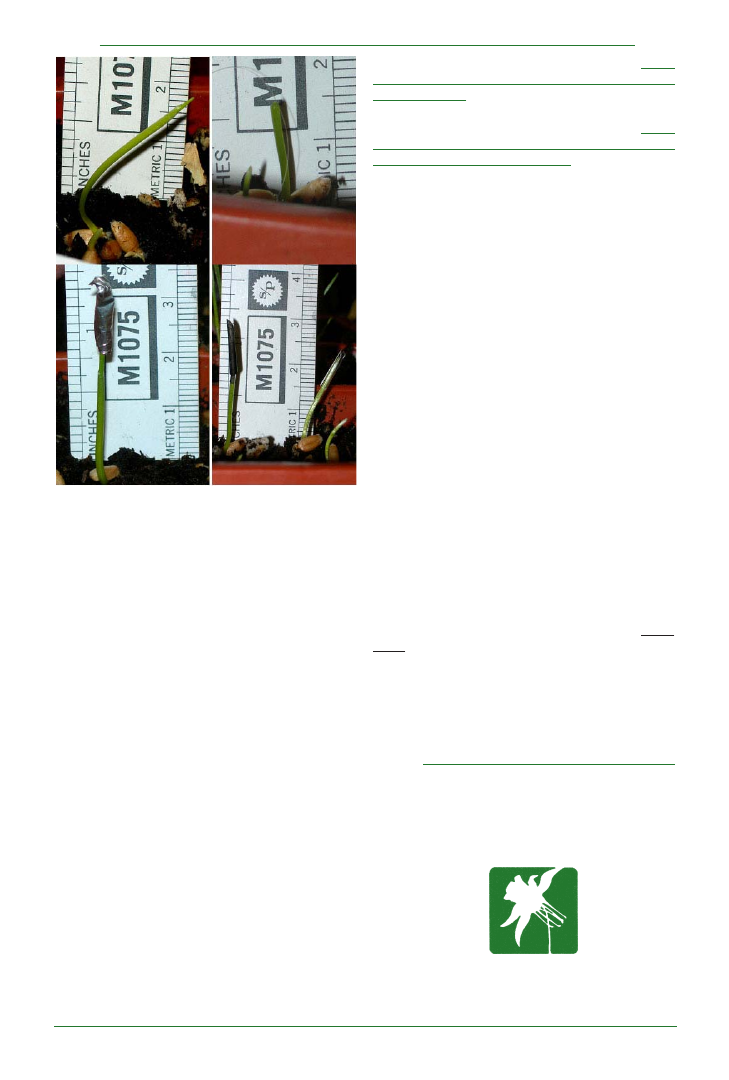

PlantingScience — BSA-led student research and

science mentoring program

The winter break is a busy time for the

PlantingScience project, as we review the past Fall

session and prepare for the Spring session of

online mentored inquiry projects.

Special thanks to Antonio Arroyo, Robyn Darbyshire,

David Giblin, Tony Haigh and his son Andrew, and

Melissa Islam for assistance preparing for the

Spring Session by testing new website features.

The Spring Session will run from Feb. 2 to Mar. 31.

Check out some of the student team plant

investigations and their conversations with online

scientist mentors at

www.plantingscience.org

. You

can search student projects in the Research Gallery.

Approximately 100 new mentors were welcomed to

the program over the winter break. What a thrill to

see such commitment from BSA members at

various stages of their careers as well as from

scientists representing diverse societies. We

deeply appreciate the time you are volunteering to

share your passion for plants and understanding of

science with middle school and high school

students.

The next call for new mentors and an announcement

inviting graduate students to join the 2009-2010

Master Plant Science Team, a special set of mentors

with a greater time commitment, will go out late

spring/early summer.

Since the 2005 proof-of-concept forerunner to

PlantingScience, the project has changed as well

as grown. Originally, middle school, high school,

and college students shared the same website

platform and pool of scientist mentors. To

encourage peer-to-peer mentoring, we restructured

college participation to College Collaborations

http:/

/college.plantingscience.org/.

A handful of 2-year

and 4-year professors are dedicated to providing

their students with online science collaboration

experiences. Are you interested in joining them?

Or organizing sister-school interactions?

As you see there are a wide variety of opportunities

in addition to mentoring in PlantingScience, including

authoring new inquiries and reviewing curricular

modules.

Please feel free to contact

chemingway@botany.org

if you are interested in

these.

Summer Opportunities for High School Teachers

— apply by Mar. 9

We invite high school teachers to apply for two

residential NSF-funded Summer Institutes held at

Texas A&M University. Brochures and applications

are available online. Apply by March 9 for guaranteed

consideration.

PlantingScience Summer Institute (June 8-16).

Collaborate with plant scientists on plant genetics

and pollination investigations. Explore strategies

for supporting student inquiries in your classroom

and online communication with scientist mentors.

The Summer Institute is designed especially for

high school teachers to integrate plant biology

content with authentic science learning experiences

that allow students to think and work like scientists.

Participants have opportunities to work with Paul

Williams, Larry Griffing, and Beverly Brown, who

authored PlantingScience units.

http://www.plantingscience.org/

Plant IT Careers, Cases and Collaborations

Summer Institute (July 6-17). Plants and people,

one of today’s critical interdisciplinary areas, is the

content focus of this workshop for high school

teachers. Participants will explore investigative

cases on ethnobotany and seed technology and

learn ways to customize collaborative, active learning

cases that are rich in data, tools, and real world

applications, and practice new investigative case

skills with students who participate in summer

camps.

http://www.myPlantIT.org/

Spotlight on BSA Member Contributions to

Science Education

Announcing an innovative Research Coordination

Network in the Undergraduate Biology Education

Track to mobilize undergraduate faculty and reform

biology courses: “Preparing to Prepare the 21st

Century Biology Student: Using Scientific Societies

as Change Agents for the Introductory Biology

Experience.”

Gordon Uno of The University of Oklahoma and the

American Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS), in

collaboration with key national scientific and

biological societies, will establish a coordinated

network involving the full spectrum of biologists and

undergraduate faculty to articulate a shared vision

of biology education of the future, to outline a model

of introductory biology experiences focusing on

how best to prepare biology students to meet that

future, and to coordinate a permanent network that

connects individuals, projects, and societies actively

8

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

engaged in the reform of undergraduate biology

education to increase capacity in the reform

movement.

Over the next 5 years, the RCN-UBE will host 1)

small face-to-face meetings to promote innovation

in reform activities aimed at the Introductory Biology

experience; 2) larger face-to-face meetings to

coordinate disparate approaches in Introductory

Biology and to increase the use of existing best

practices throughout scientific societies; and 3) a

communication network linking scientific societies

and their members to promote widely both

innovation and adaptation of best practices and

research in biology education.

Science Education in the News

U.S. Science Scores Stagnant in International

Study—Recently released results of the 2007

Trends in International Mathematics and Science

Study (TIMSS) show no change in U.S. fourth and

eighth graders average science scores since the

1995 study. Among the countries assessed, the

US ranked 8

th

in average science scores for 4

th

graders, but dropped to 11

th

place among scores

for 8

th

graders.

http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results07.asp

Slow but Steady Progress of Women on College

Boards—The critical mass of women

representation needed to make an impact is gaining

ground in more institutions, with at least three

women now serving on 90% of boards, according

to a national survey conducted by the Cornell Higher

Education Research Institute. Since the 1980s

women have garnered more positions as trustees

(up from 20% to 31%) and chairs (up from 10% to

18%) on college boards.

h t t p : / / w w w . i l r . c o r n e l l . e d u / c h e r i / s u r v e y s /

2008surveyResults.html

Career Development Tips and Resources—

Whether you are crafting your first job cover letter,

considering choices between academia and

industry, or learning to manage a lab, the new

version of Science Careers’ Career Basics Booklet

Science/AAAS offers sound advice for early career

scientists. Individual chapters or the entire booklet

is available as free downloads.

http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/tools_tips/

outreach/career_basics_2009

National Plant Genome Initiative Spreads Message

to the Public—”New Horizons in Plant Sciences for

Human Heath and the Environment” is an

educational booklet for general audiences derived

from the 2007 National Research Council report

Achievements of the National Plant Genome

Initiative and New Horizons in Plant Biology. The

role of plant genomics in food crops, biofuels,

environmental stewardship, and biomedical

advances are showcased in an easily accessible,

visually appealing booklet available as a free

download.

http://dels.nas.edu/plant_genome/report.shtml

National Science Foundation Focuses Attention on

Cyberlearning—The potential to transform STEM

education through cyberlearning is immense,

according to a recent report “Fostering Learning in

the Networked World: The Cyberlearning Opportunity

and Challenge.” The Task Force responsible for

reviewing the opportunities and challenges offered

five broad recommendations to NSF, including

promoting open educational resources and

promoting cross-disciplinary communities of

cyberlearning scientists and educators.

h t t p : / / w w w . n s f . g o v / p u b s / 2 0 0 8 / n s f 0 8 2 0 4 /

nsf08204.pdf

Education and Technology Raising Profile in

Science—You might already be accustomed to

looking for the monthly Education Forum piece

published in Science. Beginning with a Special

Section on Education and Technology, Science will

increase its commitment to education coverage.

Don’t miss the Special Section in the 2 January

2009 issue.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/vol323/

issue5910/index.dtl

Editor’s Choice

Crane, Lucy and Mark Winterbottom. 2008. Plants

and photosynthesis: Peer assessment to help

students learn. Journal of Biological Education

42(4): 150-156.

This study, geared to H.S. students, chose

photosynthesis as a “conceptually challenging” topic

to investigate the effectiveness of peer assessment

at promoting a richer understanding of the material.

Can peer assessment help students learn? The

results were equivocal, but it was clear that students

learned the material as well, if not better, than with

traditional instruction. It was also clear that as a

result of their experience with peer assessment,

students felt more confident in their ability to be

autonomous learners.

D’Avanzo, Charlene. 2008. Biology Concept

Inventories: Overview, Status, and Next Steps.

BioScience 58: 1079-1085.

Concept inventories, made famous more than a

decade ago by the Force Concept Inventory in

Physics, are tests developed to measure student

understanding of particularly difficult topics.

Biologists are finally getting there. This article

9

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

provides an introduction to what they are and

references the few available or in preparation dealing

with biological concepts.

Firooznia, Fardad. 2009. An Ode to PSII. American

Biology Teacher 71: 27-30.

A scripted play to actively engage students in

performing steps of the photochemical reactions of

photosystem II, inspired by a photosynthesis play

filmed at Cornell University.

Frisch, Jennifer Kreps and Gerald Sanders. 2008.

Using stories in an introductory college biology

course. Journal of Biological Education 42(4):164-

169.

This article presents case studies of four college

professors who effectively use different kinds of

stories either to engage students at the beginning

of class or to anchor difficult concepts covered in

class.

Miller, Sarah, Christine Pfund, Christine Maidl

Pribbenow, and Jo Handelsman. 2008. Scientific

teaching in practice. Science 322:1329-1330.

The authors describe a graduate student training

program and the University of Wisconsin-Madison,

that teaches graduate students and post-docs how

to practice scientific teaching. Scientific teaching

creates a classroom that reflects the true nature of

science, engages student-active learning, and

promotes teaching as a scholarly endeavor. Less

than half of a typical 50-minute class period employs

traditional lecture (broken up into several 5-10 minute

segments). Other techniques employed include:

brainstorming, data interpretation, case study and

discussion, think-pair-share, and minute paper

sessions. Significant gains in skill or knowledge

were demonstrated for all categories tested.

Smith, M.K., W.B. Wood, W.K. Adams, C. Wieman,

J.K. Knight, N. Guild, and T.T. Su. 2009. Why peer

discussion improves student performance on in-

class concept questions. Science 323:122-124.

“When students answer an in-class conceptual

question individually using clickers, discuss it with

their neighbors, and then revote on the same

question, the percentage of correct answers typically

increases. This outcome could result from gains in

understanding during discussion, or simply from

peer influence of knowledgeable students on their

neighbors.” The authors designed their experiment

to distinguish between these alternatives and found

that peer discussion enhances student

understanding even when no member of the group

originally knew the answer.

Panijpan, Bhinyo, Pintip Ruenwongsa and

Namkang Sriwattanarothai. 2008. Problems

encountered in teaching/learning integrated

photosynthesis: A case of ineffective pedagogical

practice? Bioscience Education e journal. 12:

December.

www.bioscience.heacademy.ac.uk/

journal/vol12/beej-12-1.pdf

The authors present a number of conceptual

questions they used to evaluate understanding of

photosynthesis by secondary students and

teachers, college undergraduates and

postgraduates in Thailand. The country is different,

but the results are the same - - lecture and rote

learning is not very effective.

Applications Solicited, Editor, Plant

Science Bulletin, 2010 – 2014

Are you looking for a meaningful way to serve the

Botanical Society of America? Are you interested in

desktop publishing? Would you like to correspond

with botanical colleagues in many disciplines about

books, articles, and matters of interest to the BSA?

The BSA is soliciting applications for the 5-year

position as Editor of the Plant Science Bulletin.

If your answer to ANY of these questions is yes,

please communicate your interest to Dr. Pat

Herendeen (Chair, BSA Publication Committee).

PATRICK HERENDEEN, Chicago Botanic Garden,

1000 Lake Cook Road, Glencoe, 60022 Phone:

202/994-5828, 847-835-6956. E-mail

pherendeen@chicagobotanic.org

Applications are welcome any time and no later

than July 1, 2009. The BSA Publication Committee

will begin reviewing interested candidates during

summer of 2009.

For a description of the Plant Science Bulletin see:

http://botany.org/plantsciencebulletin/

1 0

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Dr. Steven Clemants 1954-2008

A passion for plants came early for Steve Clemants,

who went on to become one of the leading botanists

of the day. Born in Minnesota and raised in the

towns of Edina and Minnetonka, Minnesota, and

Chicago and Normal, Illinois, Steve developed a

love of nature as a young boy. He had an affection

for the flowers that grew in his family’s garden,

particularly tulips, but he especially admired

wildflowers. Throughout his childhood, his mother,

Doris, nurtured his interest, teaching him about

local wildflowers and where they grew.

After completing high school in Minnetonka, Steve

attended the University of Minnesota. He initially

majored in computer science, but he missed the

out-of-doors and his nature studies. This led him to

change his undergraduate major to botany, his

childhood love. His dual interests of botany and

computer science served Steve very well later in his

career; he was instrumental in developing a number

of important databases for plant location records.

Steve graduated from the University of Minnesota in

1976 but remained there to pursue a master’s

degree in botany with a minor in horticulture, which

he obtained in 1979.

Steve’s botanical pursuits took him to the City

University of New York (CUNY) where, working at

the New York Botanical Garden with curator James

Luteyn, he pursued a doctorate in botany. His

graduate work focused on New World members of

the blueberry family in the genus Bejaria, and this

allowed him to conduct field trips in the tropics. He

obtained his doctorate in botany from CUNY in

1984. It was during his graduate studies that his

friend and fellow graduate student Brian Boom

introduced Steve to Grace Markman, then a volunteer

tour guide at the New York Botanical Garden. They

later married.

After a brief teaching appointment at Bard College

in Annandale-on-Hudson, Steve accepted a

position as a botanist with the New York Natural

Heritage Program, and he and Grace moved to the

Albany area in 1985. Utilizing his skills in botany and

computer science, Steve developed a database of

rare plant occurrences in New York State. He also

conducted extensive fieldwork in search of rare

plants. During this time his interests in plant research

expanded beyond the blueberry family to other

families, including the rush family and goosefoot

family.

In 1989, Steve accepted a position as a research

taxonomist at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, where he

later served as director of Science; vice president of

Science, Publications, and Library; and senior

research scientist. As Steve continued his botanical

research, he developed additional interests in urban

ecology and conservation. Shortly after arriving at

the Garden, he founded the New York Metropolitan

Flora program, which has become an international

model for studying plants in urban environments.

Data from this pioneering project are now yielding

important information on how human-caused

phenomena, such as global warming and

development, are affecting the region’s plants.

During his time at BBG, Steve published dozens of

research papers. In 2006 he coauthored Wildflowers

in the Field and Forest: A Field Guide to the

Northeastern United States (Oxford University

Press) with New York Botanic Garden researcher

and photographer Carol Gracie. This book has

become one of most popular field guides for the

Northeast. It is also used as a college textbook for

field botany, enabling people to learn more about

the wild plants Steve had admired since he was a

boy. Steve also furthered botanical education by

serving on the faculty at Rutgers University and the

City University of New York.

Steve recognized the need to protect the plants he

loved so much and served on numerous committees

and boards of organizations active in local, national,

In Memoriam:

1 1

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Personalia

Warren Abrahamson Selected

Fellow of the American Association

for the Advancement of Science

Warren Abrahamson, David Burpee Professor of

Biology at Bucknell University, has spent 36 years

studying the interaction of goldenrods and gall flies

and received more than $2 million from the National

Science Foundation and other sources for his

laboratory at Bucknell. He is recognized for

“distinguished contributions to the field of biology,

particularly for discoveries about evolutionary

ecology and plant-insect interactions.”

Abrahamson has published more than 142 papers;

nearly a third of the papers are co-authored by post-

doctoral fellows, masters-level and undergraduate

students, giving them exposure to “science in the

real world,” he said. “To me, this is really neat,

because I think it crystallizes the significance of

having endowed chairs and of supporting young

faculty. We have successfully competed with higher

level research institutions for grants. The fact that

this has been done with students is significant.”

and international conservation efforts. During his

career he was president of the Nature Network;

chair of the Invasive Plant Council of New York State;

president of the board of Botanic Gardens

Conservation International’s U.S. office; historian

of the Torrey Botanical Society; chairman of the

Long Island Botanical Society; and member of the

Woodland Advisory Board of Prospect Park. He was

also codirector of the Center for Urban Restoration

Ecology (CURE), a collaboration between Brooklyn

Botanic Garden and Rutgers University, the first

scientific initiative in the U.S. established to study

and restore human-dominated lands. He served

as editor-in-chief of Urban Habitats, a peer-reviewed

scientific e-journal on the biology of urban areas

around the world, which was launched in 2003.

In 2008, Dr. Clemants was instrumental in

developing an agreement between the NYC Parks

Department and Brooklyn Botanic Garden

committing the resources of the two institutions to

the conservation of plants native to New York City,

the first comprehensive conservation initiative

targeting the City’s native plants. “Steve was a

colleague and the leader of our mutual efforts to

discover, preserve, and publicize local botanical

biodiversity,” said Adrian Benepe, NYC Parks

Commissioner. “He will be deeply missed by all

who care about natural New York and the great

beauty of its parks and wild spaces.”

Steve was a remarkably kind, giving, and patient

man, who always found time to assist students and

other members of the public who came to the

Garden with questions and requests. Shortly before

Steve’s passing, his extraordinary kindness was

displayed when he learned that a Ukrainian

colleague and his wife -- who had never before been

to New York -- would briefly be in town during a flight

layover. Steve picked them up, took them on a

whirlwind tour of Brooklyn, and returned them to the

airport in time for their flight. Gerry Moore, director of

Science at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, said, “Steve’s

extensive knowledge of botany and willingness to

help all who came to him with questions was a

combination that served the Garden and the public

well. His example inspires us to continue our

research in the plant sciences, while always finding

time to share our knowledge and our curiosity with

individuals, from kindergartners to international

researchers.”

As news of his passing has spread, BBG science

staff received messages from around the world

from colleagues who admired Steve and his work.

Peter H. Raven, president of the Missouri Botanical

Garden, said, “Steve Clemants was a bright light in

the field of botany, a lovely man who was utterly

fascinated with plants, loved people, and made a

marvelous contribution by combining his passions

into every facet of his life. No one has done a better

job in involving the public in the joy of learning about

plants, finding them, thrilling in new discoveries,

and understanding their traits. Steve’s contributions

to science were deep and numerous, and his

contributions to development of the Brooklyn Botanic

Garden over the years, through good times and

difficult ones, were of fundamental importance in

keeping that fine institution on an even keel.

His bright, friendly, pleasant personality will be

missed as much as his outstanding professional

skills, not only in research and in administration but

in education and in his ability to uplift the spirit of

everyone who knew him.”

The Dr. Steven Clemants Wildflower Fund has been

established to honor our late colleague and friend.

Steve’s widow, Grace Markman, is working with the

Greenbelt Native Plant Center to plan a living

memorial that will foster the planting of native

wildflower species in New York City parks.

Donations in his memory should be made out to

“City Parks Foundation, Dr. Steven Clemants

Wildflower Fund,” and mailed to City Parks

Foundation, c/o Greenbelt Native Plant Center, 3808

Victory Blvd., Staten Island, NY 10314.

1 2

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Dr. Gregory Mueller named Vice

President, Science and Academic

Programs at the Chicago Botanical

Garden

Dr. Mueller joined the Garden in January 2009. As

Vice President, Science and Academic Programs,

Dr. Mueller will lead the development of academic

programs of the Chicago Botanic Garden, including

plant science conservation and research; graduate

student training programs; the Lenhardt Library

and the Joseph Regenstein, Jr. School of the Botanic

Garden. Dr. Mueller will play a critical role in guiding

the expansion of the Garden plant science and

“We are using a multitude of approaches, including

genetics, behavior and ecology, to study how the

interaction works and how the plant defends itself,

how insects find plants and how natural enemies

have evolved in respect to the gall fly,” he said. “All

of that helps us to understand evolutionary ecology

of the interaction. We’re looking at ecological

interactions and how they evolve, how specialization

occurs, how biodiversity is created on this earth. We

mammals are a tiny part of the diversity, but insects

and plants represent the vast majority of the

biodiversity described on earth.” Abrahamson and

his collaborators discovered that some goldenrod

plants develop a higher tolerance to their predators

while others produce terpenes, an odor that is toxic

to insects that feed on them.

Abrahamson is co-author of the book, Evolutionary

Ecology Across Three Tropic Levels: Goldenrods,

Gallmakers & Natural Enemies, (Princeton

University Press, 1997) and edited, Plant-animal

Interactions, (Macmillan, 1987).

Randy Moore Wins National

Evolution Education Award

Randy Moore, a professor in the University of

Minnesota’s College of Biological Sciences, has

been named winner of the National Association of

Biology Teachers Evolution Education Award.

Moore will receive the award, given to one K-16

biology teacher annually, at the association’s annual

meeting on Oct. 17 in Memphis, Tenn.

For nearly 30 years, Moore has taught biology

based on evolution, incorporating it as the unifying

theme of biology as well as his classes. “There is

no controversy among biologists over whether

evolution occurs, nor are there science-based

alternative theories,” Moore said. “Teaching

evolution as a unifying theme is the best way to

show students what biology is all about and to help

them understand our world. It’s one of the most

important, useful and liberating ideas in science.”

Moore has also worked outside the classroom to

improve public understanding of science by advising

states on science education guidelines, conducting

teacher workshops and media interviews and

building dialogue between scientists and religious

groups.

“I was raised to understand and respect religious

traditions, but I strongly oppose the teaching of

creationism in science classes,” Moore said.

Moore has authored four books on evolution, most

recently “More Than Darwin: An Encyclopedia of the

People and Places of the Evolution-Creationism

Controversy,” which he wrote with his colleague,

Mark Decker.

As a professor in the biology program, which is run

by the College of Biological Sciences, Moore teaches

introductory biology, a popular class entitled “The

Evolution-Creationism Controversy,” and a learning

abroad course called “”Biology of the Galapagos,”

which takes students on a research-based trip to

see “evolution’s workshop.”

To view a multimedia presentation on “Biology of

the Galapagos,” go to

http://www.cbs.umn.edu/

main/multimedia/galapagos/

The education award, which is given for innovation

in classroom teaching and community education

efforts to promote the understanding of evolution, is

co-sponsored by the American Institute for Biological

Sciences and the Biological Sciences Curriculum

Study.

Moore, who has earned numerous other teaching

awards from local and national organizations, holds

a doctorate in biology from the University of California,

Los Angeles. He is available for interviews about

evolution in the classroom and the evolution-

creationism controversy.

1 3

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

conservation efforts, as the Garden grows in its role

as an international center for research in rare and

endangered plant biology, ecological restoration,

horticultural ecology and soil science.

Dr. Mueller has served as the President of the

Mycological Society of America and as International

Coordinator for Fungal Programs at the Costa

Rican National Biodiversity Institute. He is a member

of the International Union for the Conservation of

Nature, Species Survival Commission, Fungal

Specialist Group; and the Science Advisory Council

for the Illinois Chapter of the Nature Conservancy.

He also serves as Associate Chair and Lecturer,

Committee on Evolutionary Biology at the University

of Chicago; and as Adjunct Professor, Department

of Biological Sciences at the University of Illinois at

Chicago.

Dr. Mueller’s research focuses on the biology and

ecology of fungi, especially mushrooms, providing

vital information for the management and

conservation of temperate and tropical forests,

particularly in the Chicago region, Costa Rica,

Guatemala, and China. He has authored six books

and nearly 100 journal articles.

Dr. Mueller worked for more than 23 years at the

Field Museum, most recently as the Curator of

Mycology in the Department of Botany. He was

Chair of the Field Museum’s Department of Botany

from 1996 to 2005, during which time the Department

renovated its collections facilities, added lab and

research space, and significantly increased the

size of its curatorial and professional staff.

“My work will focus on expanding an already

outstanding science program that will continue to

address the critical needs of the 21st century. I

would like to build capacity, make connections with

other organizations and botanic gardens engaged

in similar work and enhance people’s ability to

study the world around them,” Mueller said.

“Greg’s many years of work with the Field Museum,

the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University

of Chicago and Chicago Wilderness offers the

Chicago Botanic Garden a unique opportunity to

combine the complementary strengths of each

organization to solve the complex issues facing the

plant life of the Chicago area, the nation, and the

world. Bringing these organizations together in a

unified effort to enhance knowledge and

understanding of plant life holds the promise of

making Chicago an international center of plant

conservation biology and education,” said Sophia

Siskel, president and CEO of the Chicago Botanic

Garden. Mueller holds B. A. and M. S. degrees in

Botany from Southern Illinois University and a Ph.D.

in Botany from the University of Tennessee.

Peter Raven Receives Lifetime

Achievement Award from the

National Council for Science and

the Environment

Peter Raven, president of the Missouri Botanical

Garden, has received the National Council for

Science and the Environment (NCSE) Lifetime

Achievement Award. The award, “For a

Distinguished Career as an Innovative Leader

Advancing Scientific and Public Understanding and

Conservation of Biological Diversity,” was presented

at a special ceremony in Washington D.C. on Dec.

8, during the 9

th

National Conference on Science,

Policy and the Environment: Biodiversity in a Rapidly

Changing World.

Peter Raven is one of the world’s leading botanists

and advocates of conservation, biodiversity, and a

sustainable environment. For three decades, he

has headed the Missouri Botanical Garden, an

institution he nurtured into a world-class center for

botanical research and education, and horticultural

display. Described by Time magazine as a “Hero for

the Planet,” Raven champions research around the

world to preserve endangered plants.

Raven is the recipient of numerous prizes and

awards, including the prestigious International Prize

for Biology from the government of Japan and the

U.S. National Medal of Science. He has held

Guggenheim and John D. and Catherine T.

MacArthur Foundation fellowships. Raven was a

member of President Bill Clinton’s Committee of

Advisors on Science and Technology. He also

served for 12 years as the home secretary of the

National Academy of Science and is a member of

the academies of science in Argentina, Brazil, China,

Denmark, India, Italy, Mexico, Russia, Sweden, the

U.K., and several other countries.

“Peter Raven has demonstrated how to be both a

world-class scientist and a world-class

conservationist,” noted NCSE Senior Scientist David

Blockstein. “His career has combined scientific

research on plant evolution and diversity, leadership

on multi-national collaborative scientific and

conservation endeavors, education and outreach

at the beautiful Missouri Botanical Garden, and

passionate advocacy for humanity to care for our

planet and all its inhabitants.”

Raven received the distinguished award alongside

fellow biodiversity pioneers George Rabb and

Edward O. Wilson.

1 4

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Bringing Modern Roots to a

Traditional Collection

After 10 years in New York City,

Ken Cameron was Ready for a

Change.

As the director of the primary molecular research

lab at the New York Botanical Garden, Cameron

had been working at a world-renowned institution

with a first-rate team of botanists and had access

to some of the finest resources available. But

something was missing.

Ken Cameron, director of the Wisconsin State Herbarium

and associate professor of botany, searches through the

catalogued plant specimens inside Birge Hall.

Photo: Bryce Richter

“I had one of the greatest jobs in my field … But in

the back of my mind I always felt a little unfulfilled,

because I like to teach, and I like to interact with

students, and I like the academic environment of a

university,” he says.

“There were maybe three or four places that if they

ever came knocking or if a position opened up I

might consider it. And the University of Wisconsin in

Madison was one of those places.”

Cameron joined the faculty earlier this year as an

associate professor of botany and director of the

Wisconsin State Herbarium. He cites the botany

department — one of a relatively few remaining

university botany departments, since most have

folded into larger biology departments — as a

strong draw, along with the mix of teaching, research

and administrative duties offered by his joint

appointment.

He brought many of his research interests with him,

including a specialization in the study and

classification of Vanilla and related orchids. He

finds this appealing because of their unusual mix

of complex and primitive characteristics. While his

roots lie in using genetic techniques to decipher

plants’ evolutionary relationships, he also has

extensive experience working in the field and a deep

appreciation of the importance of traditional natural

history collections like the herbarium.

A herbarium is a collection of preserved and

catalogued plant specimens, usually pressed and

dried, used for research and teaching. “The main

purpose is to document plant variation and diversity,”

Cameron says. “People often are surprised to find

that we don’t just collect one of everything, but in

many cases we might have dozens or up to 100

specimens of the same species. The main reason

for that is obvious if you considered the human

species as an example. You couldn’t define Homo

sapiens by one human, you’d have to see the whole

range of variation. We do the same with plants —

and you’d be surprised how variable [they are].”

UW–Madison’s collection is one of the largest at

any public university. Established in 1849, shortly

after the university was founded, the Wisconsin

State Herbarium contains more than one million

specimens of everything from fungi and mosses to

grasses and flowering plants — each carefully

labeled, mounted in a paper folder, and filed in one

of the hundreds of cabinets that fill the herbarium’s

home in Birge Hall. The herbarium also has an

extensive collection of maps, field notes and

botanical literature.

Herbaria hearken back to a time when scientific

study emphasized natural history collections, which

are now largely overshadowed by modern

laboratory-based techniques like genetics and

molecular biology. But Cameron stresses the

importance of combining the modern with the

traditional to answer basic questions about plant

diversity, relationships and evolution.

“There is a notion that a herbarium is kind of an old-

fashioned, dusty-museum kind of a place that maybe

doesnt have relevance in this new, modern,

molecular age. But I would strongly say that is a

false impression,” he says. “The old techniques

and tools are just as relevant as the new.”

The historical context offered by the herbarium is

also helping studies of contemporary issues such

as climate change and the spread of invasive

species. “What we’ve done, without thinking about

it, is to establish a historical record of which plants

were growing where, when they were flowering, and

what the land features were like,” Cameron says.

“For example, herbarium specimens have been

used in the last few years to document climate

change. Plants are usually collected when they’re

in flower, and by plotting the flowering dates of

1 5

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Courses/Workshops

National Tropical Botanical Garden

Fellowship for College Biology

Professors

Program Operation: June 1-12, 2009

Deadline to Apply: March 13, 2009

Notification of Acceptance: March 20, 2009

COURSE DESCRIPTION

The National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) will

conduct another exciting Fellowship for College

Professors of Introductory Biology at The Kampong,

Coconut Grove, Florida.

The goal of the Fellowship is to improve the quality

of teaching in introductory biology classes at the

undergraduate level. Facilitated by Professor P.

Barry Tomlinson of Harvard University and Dr. Paul

Alan Cox, CEO/Director of the Institute for

Ethnomedicine, the course is designed to show

instructors how to use examples from tropical plants

in discussing issues of form and function, evolution,

and conservation. Fellows will develop teaching

modules to be shared and implemented in the

introductory biology classroom. Basically, we are

looking for the very best biology faculty, those who

can fire the imagination of major and non-major

biology students. Although botanists will be

considered, we also welcome applications from

faculty who lack previous botanical experiences, as

well as those who have not previously worked in the

tropics. The Fellowship will be limited to 12

Professors.

Applications must include:

• Two letters of recommendation.

• Complete curriculum vitae.

• Copy of the most recent teacher evaluation.

• A non-refundable $40 USD application fee in the

form of a check or money order made payable to the

National Tropical Botanical Garden.

The Fellowship will cover the most economical

roundtrip airfare to The Kampong, Florida,

accommodation and meals, tuition and fees, texts,

equipment, and ground transportation.

Requests regarding the Fellowship for College

Biology Professors must be directed to:

Director of Education

National Tropical Botanical Garden

3530 Papalina Road

Kalaheo, HI 96741 USA

Tel: (808) 332-7324, ext. 225 or 226

Fax: (808) 332-9765

Email:

education@ntbg.org

Website:

www.ntbg.org

The mission of the National Tropical Botanical Garden is to

enrich life through discovery, scientific research,

conservation, and education by perpetuating the survival

of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical

regions.

certain species, especially spring-blooming plants,

researchers have been able to show that a lot of our

spring wildflowers are blooming progressively

earlier and earlier.”

As the herbarium’s uses grow, he is also hoping to

expand its audience on campus, throughout the

state and even worldwide, by moving many of its

resources into a digital domain. As of this summer,

the Wisconsin Botanical Information System

(WBIS), an online repository of information about

the state’s plants, fungi, algae and lichen, now

contains data on the herbarium’s entire collection

of Wisconsin vascular plants — more than a quarter-

million records — plus an additional 87,000

specimens from other herbaria in the state.

With the vascular plant database virtually complete,

Cameron and the other herbarium staff are now

developing a similar database of their impressive

lichen collection. The Wisconsin State Herbarium

is also part of a large, multi-institutional project to

scan and digitize many of the world’s most valuable

plant samples, those known as “type specimens”

— the individual physical specimens chosen by

scientists to represent their species. Wisconsin’s

type images will be combined with those from other

institutions to create a standardized online library.

“When I got here, there was already a foot into the

21st century with these databases. My hope is that

my legacy will be to expand that online presence

and our public presence,” Cameron says. “We’re

this gem of an incredible resource tucked away in

Birge Hall that very few people in the state realize

exists.”

by Jill Sakai

1 6

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Symposia, Conferences,

Meetings

13th Natural History Conference

Celebrating 25 years of Annual

Conferences at the Gerace

Research Center, Bahamas

When: June 18-22, 2009

Where: Gerace Research Centre, located on San

Salvador Island, one of the outermost of a chain of

some 700 islands that comprise The Bahamas

Description: Since 1984, scientists utilizing the

Gerace Research Centre have taken part in biennial

meetings to promote a better understanding of the

investigations being conducted on San Salvador,

the Bahamas, and the wider Western Atlantic. The

material presented at these meetings covers a

broad range of topics, including marine

conservation, archaeology, invasive species, and

plant-insect interaction.

Keynote Speaker: Fiorenza Micheli, Hopkins Marine

Station, Stanford University

Keynote Title: TBA

Co-Chairs: Eric Cole, Biology Department, St. Olaf

College; and Jane Baxter, Department of

Anthropology, DePaul University

Organizer: Thomas Rothfus, Gerace Research

Centre

Estimated Cost:

Registration, including Proceedings Volume

$110.00

Airfare: Ft. Lauderdale-San Salvador $510.00

Room and Board at the GRC

$296.00

Total

$916.00

Student Room and Board $240.00

Deadlines: The deadline for Registration is March

31, 2009. The deadline for Abstract submission is

April 16, 2009.

ICPHB 2009

International Conference on

Polyploidy, Hybridization and

Biodiversity

May 17 – 20, 2009 – Palais du Grand Large

Saint Malo – FRANCE

The International Conference on Polyploidy,

Hybridization and Biodiversity aims at promoting

knowledge exchanges and discussions on the

latest developments concerning these major drivers

of genome shaping and speciation. A wide range of

topics will be covered such as the consequences

of polyploidy on biodiversity, hybrid and polyploid

speciation, meiosis and fertility in polyploid species,

genome evolution and structure, transposable

elements and DNA methylation, epigenetics and

gene regulation, heterosis, phenotypic variation ...

The conference will focus sessions on all these

areas and therefore illuminate mechanistic and

evolutionary insights into many fundamental

phenomena in biology. This undertanding is critical

for management and conservation of Biodiversity

as well as for breeding programs as most important

crop species are relatively recent polyploids.

Deadlines

• February 28, 2009 : abstract submission deadline.

• March 10, 2009 : registration fees are cheaper

before this date.

• April 10, 2009 : refund for cancellation deadline

Preliminary program

The following scientific sessions are planned:

• S1 - Polyploidy and hybridisation as a source for

genetic and phenotypic novelties

• S2 - Long-term polyploid evolution: Comparative

genomics, gene retention-loss, diploidization

• S3 - Polyploidy: Effects on genome organization

and structure

• S4 - Mechanisms for gene expression in plant

polyploids (transcriptome, proteome)

• S5 - Hybridization, polypoidy and epigenetics

• S6 - Meiosis, reproduction in polyploids

• S7 - Heterosis, gene dosage

• S8 - Reticulate evolution, history of Polyploids,

phylogeny

• S9 - Ecological consequences of hybridisation

and polyploidy, invasion, diversification

For more information see:

http://

www.icphb2009.univ-rennes1.fr/index.php

1 7

Plant Science Bulletin 55(1) 2009

Positions Available

Director, Sternberg Museum of

Natural History

STERNBERG MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY:

The Sternberg Museum of Natural History occupies

a completely renovated (completed in 1999), unique

building adjacent to Interstate-70 Highway in Hays,

Kansas. Its 101,000 square feet of floor space

accommodates both public areas and collection

management space. The collection space houses

extensive research collections representing the

disciplines of mammalogy, ornithology, herpetology,

ichthyology, entomology, botany, vertebrate

paleontology, and paleobotany. The total number

of specimens in these collections is in excess of 3

million, and the Museum thus serves as a major

research resource for the academic departments

of Biological Sciences and Geosciences. Public

exhibits of the Museum are internationally known

and focus on animals of the Cretaceous time period.

These are supplemented with a program of

temporary exhibitions, both leased and prepared

in-house, relating to a broad spectrum of natural

history topics. Educational programming for adults

and especially for children is designed to instill a

fascination for plants and animals in their

environment. The new Kansas Wetlands Education

Center, located 70 miles away at the largest wetland

area in the central United States, is a branch of the

Sternberg Museum of Natural History that functions

to educate the public about the importance, history,

plant and animal inhabitants, and conservation of

wetlands.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE DIRECTOR: