BULLETIN

SPRING 2008

VOLUME 54

NUMBER 1

2@2

PLANT SCIENCE

ISSN 0032-0919

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Leading Scientists

and

Educators

since 1893

Science, Success, and Satisfaction. A Look at Planning a Botany Conference......................2

Experiences of a local arrangement committee for a large scientific Conference.....................6

The Three C’s: Early Botanical Leaders at the Univesity of Chicago......................................12

News from the Society

Picturing the Past.............................................................................................................15

Report from the Office.....................................................................................................15

American Journal of Botany..........................................................................................16

BSA Science Education News and Notes....................................................................17

Editor’s Choice.................................................................................................................19

Preview of Botany 2008 - - University of British Columbia Botanical Garden........19

Announcements

In Memoriam

Donald Robert Kaplan (1938-2007)...............................................................20

Richard Goodwin (1910-2007)........................................................................22

Personalia

Crop Science Society Honors Missouri Botanical Garden’s

Peter Raven.......................................................................................23

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings

Student Research in Plant Biology and Conservation Symposium.........23

3rd Meeting of the International Society for Phylogenetic

Nomenclature...................................................................................23

Fourth International Conference: Comparative Biology of the Mono-

cotyledons and The Fifth International Symposium: Grass

Systematics and Evolution.............................................................24

Courses/Workshops

A Short-Course in Tropical Field Phycology..............................................24

Award Opportunities

Colorado Native Plant Society ......................................................................24

Positions Available

Senior Vice President of Plant Science and Conservation, Missouri

Botanical Garden..............................................................................................25

Botany Fellow- Wellesley College Botanic Gardens..................................25

Other

Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Receives Fletcher Jones Foundation

Funding.............................................................................................................26

Botanic Gardens Conservation......................................................................................26

Lenhardt Library Schedule of Exhibits..........................................................................27

The New York Botanical Garden Announces Collaborative Campaign to

Barcode all 100,000 Trees of the World........................................................................27

Books Reviewed..............................................................................................................................28

Books Received................................................................................................................................47

BSA Contact Information...............................................................................................................47

BOTANY 2008..................................................................................................................................48

2

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Botanical Society of America

Business Office

P.O. Box 299

St. Louis, MO 63166-0299

E-mail: bsa-manager@botany.org

Address Editorial Matters (only) to:

Marshall D. Sundberg, Editor

Dept. Biol. Sci., Emporia State Univ.

1200 Commercial St.

Emporia, KS 66801-5057

Phone 620-341-5605

E-mail: psb@botany.org

ISSN 0032-0919

Published quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 4475 Castleman Avenue, St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299. The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of

the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Periodical postage paid at St. Louis,MO and additional

mailing office.

2007 was a good year for the Botanical Society:

membership was up; we were very successful in

seeking external support to fund PlantingScience;

and we had a historic joint meeting with the Plant

Biologists (who were the Plant Physiologists when

we last met jointly 3 decades ago). 2008 looks to be

GREAT! As we start the new year there are two major

changes in the Plant Science Bulletin. The first will

not be noticeable, but as of the first of the year both

the American Journal of Botany and the Plant Science

Bulletin (PSB) are being produced by a new printer,

Sheridan Press. The second will be very noticeable,

and make the PSB more timely and useful. For the

past year we have been posting all position

announcements on the BSA web page as soon as

they are received, rather than waiting for the next

hard-copy issue of the PSB. With volume 54 we will

begin to post all announcements on the web page

as they are received in addition to publishing them

in PSB on a quarterly basis.

As I write this in January, staff are running a workshop

in the Society Office for St. Louis teachers coming

on-board for PlantingScience this spring. This

summer the annual meeting is returning to the site

of BOTANY 80 for another joint meeting with the

Canadian Botanical Association (CBA/ABC) at the

University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Another

big meeting in a big venue. With that in mind we

focus this issue on what goes into planning a major

scientific conference. In our first article, the BSA

Conference Manager, Johanne Strogan, describes

the process for site selection and arrangements

that go into planning our annual meeting. In the

follow up article, David Spooner and his colleagues

at U.W. Madison describe their experience as the

local arrangements committee for a major

international meeting. Hopefully these articles will

stimulate some of you to consider hosting a future

BSA meeting; you will certainly have a better

understanding of what is involved! Finally, we provide

a highlight from last year’s meeting- a contribution

Science, Success, and

Satisfaction

A look at Planning a Botany

Conference

Finding the appropriate venue for a Botany

Conference is more than throwing a dart at a map!

There are many factors that the Program Committee

and I consider before contracts are signed and we

head toward the next meeting site. The process

starts many years before the first presentation

begins and the first cup of coffee is poured!

In 2000 when the Botanical Society of America

decided to break away from the American Institute

of Biological Sciences, the goal was to produce

successful meetings that meet the needs of the

membership. Success can be measured in many

ways, but the two areas that are most important to

the majority of members are the quality of the

scientific program and overall satisfaction with the

meeting experience. As Conference Director, my

main focus is not the science itself (that’s up to our

very capable members), but member satisfaction

with the meeting. This means involving the Program

Committees of all the sponsoring societies in

selecting the sites and negotiating the best

arrangements possible—juggling the many factors

of location, location, location, cost, ease of

transportation to and within the area, housing for

attendees, cost, food and beverage, opportunities

from Nels Lersten on the early history of botany at

the University of Chicago.

-the editor

3

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

Editorial Committee for Volume 54

Joanne M. Sharpe (2009)

Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens

P.O. Box 234

Boothbay, ME 04537

joannesharpe@email.com

Nina L. Baghai-Riding (2010)

Division of Biological and

Physical Sciences

Delta State University

Cleveland, MS 38677

nbaghai@deltastate.edu

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

Samuel Hammer (2008)

College of General Studies

Boston University

Boston, MA 02215

cladonia@bu.edu

Jenny Archibald (2011)

Department of Ecology

and Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick (2012)

Department of Biology

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

for extracurricular activities, preferences for

academic campuses or professional conference

facilities, and the ever-important coffee!

Site Selection—Size Does Matter

Much time, effort, and thought go into the site we

choose. The site needs to be large enough to hold

the meeting comfortably. As the membership of the

Botanical Society of America continues to grow,

conference attendance also continues to grow:

from just under 800 attendees in Portland in 2000,

to over 1200 in Chico in 2006. We are a strong

presence in any city we visit, and we contribute

significantly to the local economy. It has been

estimated that a conference of 1000 attendees can

bring as much as $750,000 to the host city. This

includes hotel rooms, food and beverage, attendee

spending, and recreation, as well as wages to hotel

staff and workers.

With growth comes growing pains. A typical Botany

conference requires 10-15 concurrent session

rooms each day, preferably, at least 26,000 sq ft of

contiguous space for our Exhibit Hall and scientific

poster displays, which are a large and critical part

of the meeting. These requirements somewhat

limit the venues we can consider. For example,

Hotels and conference centers traditionally have

ballrooms that can accommodate our Exhibit Hall

needs. It is rare that an academic campus venue

can. For example, one campus wanting to be

considered for a future meeting has proposed that

we use their hockey arena for the Exhibit Hall. The

Director of Conference Services promised to take

up the ice—no sense having you all slip, slidin’

away. Then again, it is a hockey arena…with all the

ambience of a hockey arena!

On the other hand, campus venues have a virtually

unlimited amount of meeting space ranging from

small classrooms to large auditoriums. This is a

plus and makes arranging the scientific program a

cinch. One drawback, however, is that sometimes

these classrooms and auditoriums are a bit far from

each other–which makes it difficult to session hop.

Getting to the coffee breaks in the Exhibit Hall can be

a hike as well. If session hopping is important to you

and you have to walk too far to take advantage of the

free coffee, then your satisfaction goes way down.

(This is evident from your responses to the post-

conference surveys.)

One of the major factors in choosing a site, which is

tied closely to member satisfaction, is, of course,

cost. From the beginning, the BSA and partner

societies decided that the annual conference was

not to be a major moneymaker. The most important

goal was and is to make the meeting as affordable

as possible to enable as many members and

students (future members) to attend as possible.

Financial goals were also to cover costs, have

some seed money for future meetings, and share

any profit among the participating societies. In all

but one year since 2000 we have been able to share

a small profit among our partners.

Negotiating Contracts

A considerable amount of negotiating is involved in

drawing up a successful meeting contract. Many

factors need to be considered to make the event a

win-win for Botany as well as the venue. An

advantage of a hotel or conference center is that they

will consider the entire meeting package and can

help reduce some costs based on the strength of

other expenditures. For example, we have significant

food and beverage expenditures at a Botany

conference; because of this we could have all or part

of the meeting space fees waived. For example, in

Austin (Botany 2005), we were able to use all the

meeting space we needed with no charge. We filled

our negotiated room block and held almost of the

Food and Beverage events in the hotel. This saved

us over $25.000.

It is very important that attendees take advantage of

the negotiated room rates that are offered with hotel

4

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

registration. If we can guarantee that 80-85% of

attendees will stay at the host hotel, this also can

result free meeting space. If we can give the Hotel

something they can give us something in return.

In contrast, college campuses have discovered that

summertime conferences can be a cash cow.

Empty rooms while school is not in session can be

turned into significant revenue streams. Traditionally

each department or facility controls the price of their

space. Campus catering controls food and beverage

costs. The residential life office controls the price of

dorm space. And the Conference Administration

Department charges a non-negotiable

administrative fee per each attendee. These fees

can add up: We have been quoted from $7.50 to

up to $100.00 per person for administrative fees.

An advantage of college campuses is that they have

been becoming “technology savvy” Most meeting

space classrooms are outfitted with LCD projectors

and screens, and in some cases, built-in computers.

This results in a cost savings in Audio Visual

dollars. The average conference spends up to

$50,000 on AV.

The possibilities for negotiating food and beverage

costs can also vary greatly between venues. A

gallon of Peet’s coffee on campus in Chico (Botany

2006) was $28.00, in contrast with $92.00 per

gallon for coffee (plus tax and service charges) at

the Hilton conference center in Chicago. (Botany/

Plant Biology 2007) (Just FWIW we were able to get

Starbuck’s coffee in Chicago at no additional charge.)

This fee is significant as Botany conference

attendees consume a lot of coffee!

Banquets

In the past, the main purpose of the BSA Banquet,

always a formal affair was to recognize the major

award winners in Botany. It also was, and remains,

an opportunity for the incoming BSA President to

share his/her area of interest. As times have

changed, the formality has relaxed but the event is

still important for the Society.

Banquets are also seen by catering departments

as a way to make “big bucks.” When considering a

venue we ask for menus—and often the only

affordable (for our normal banquet ticket price)

option is the traditional “rubber chicken.” One way

around this has been to work with the catering

department and ask what they can do for a ticket

price of, say, $45 - 50. This gives the chef some

room for creativity, and you, the attendee, a better-

than-average banquet dinner…accompanied by

sometimes lengthy speeches, which are free!

The banquets in recent memory contrasted, again,

depending on the venue. For a $50.00 banquet

ticket in Chico, attendees enjoyed a sprawling

buffet in a great setting – a beautiful lawn on campus,

perfect weather, under the stars. After that highly

successful event (as judged by high satisfaction in

the post-conference surveys), we approached

Chicago with an idea of a mini-”taste of Chicago.”

The menu was to include famous Chicago-style

pizza and hotdogs. If we added a vegetarian option

and ice cream sundaes for dessert the cost would

be $35.00 per person. (The lowest priced banquet

meal on the traditional Hilton conference menu was

$65.00 plus 10% tax and 20% gratuity – for chicken.)

We charged $25.00 to encourage people to attend,

and the BSA picked up the difference.

The idea was a good, even if in actuality the mini-

”taste of Chicago” was rather bland. The point is we

were trying to keep attendee cost in control and

attain good attendance at an important event. To

some extent, it worked. Almost 325 people were

there to honor the new awardees and to welcome

the new president.

Getting there

Traveling to the conference is one of the three

biggest expenses that people have in attending a

conference. (Housing and Registration fees are

the other two.) In weighing the total cost of one

venue vs. another, we take into account the travel

costs. Since the 2000 meeting we have been able

to offer travel discounts with either Delta or American

Airlines. This information is always posted on the

conference website. We have also been able to

offer Avis rental car discounts. With the popularity

of online discount travel very few attendees take

advantage of these discounts. And with good

reason…to save money. But by using these

discounts it can result in free air travel and free car

rentals for planning the next conferences, bringing

down a somewhat hidden cost in producing the

conference.

Travel is one area where there can be a big difference

between campus and conference center venues.

Air travel to the larger cities or airline hubs tends to

be cheaper and easier than out-of-the-way campus

venues. Airfare and other travel to Chico, for

example, was a bit more expensive and challenging

than to Chicago or Austin, Texas (Botany 2005).

Hotel Rates

In the months before September 11, 2001, the hotel

industry was struggling; after this fateful day, leisure

travel dropped off even more and the convention

business slumped. Many people were reluctant to

travel, and meetings were cancelled. At this time,

hotels and convention centers scrambled to book

space, and incredible deals were made. We

negotiated highly favorable room rates for several

years.

5

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

As time has passed, the industry as a whole has

rebounded, and prices are going up. In July, 2007,

USAToday quoted the average price of a hotel room

had reached $100.00 for the first time ever.

Unfortunately for attendees and for the meeting

industry, this is a trend that is not likely to reverse in

the near future, if ever!

We have been able to host the Botany conference

in some really nice places due to creative negotiating.

In Austin in 2005, for example, we booked the

meeting before the hotel was even completely built.

I had a hard-hat tour of the building site, complete

with a ride up the outside of the hi-rise building in an

open-air elevator. We were able to secure a room

rate of $112.00 for the meeting by booking in 2001

at pre-opening prices. During the Botany 2005

conference another planner friend of mine came to

visit our meeting. She liked the hotel and was

quoted a room rate for 2008 of $152.00. She has a

larger meeting and would bring in more revenue,

but the price had increased by 74%!

The bottom line in Austin was that we secured a

good rate at an attendee-friendly conference hotel

that was easy to get to in a city that had lots to do

when sessions were over. At the Chicago Hilton

(Botany/Plant Biology 2007), conference center, we

were able to negotiate the government rate for our

room block, which was significantly less than regular

rooms. Again, Chicago was an attractive venue

because the room rates were favorable, it’s a great

city, easy to get to with lots of opportunities for things

to do outside the meeting. Chicago was also

attractive as a site for the joint meeting due to the

increase in buying power of several societies. BSA

and the traditional society partners would never be

able to meet in Chicago by ourselves.

Another more subjective issue that is high on the

satisfaction meter is the ambience of the meeting.

Madison (Botany 2002), Snowbird (Botany 2004),

Chico, (Botany 2005), and Austin, (Botany 2006) are

among your favorites according to post- conference

surveys. Chicago (2007) and Mobile (Botany 2003)

lacked the ambience of these other meetings. In

considering a venue, we also look at what is around

the area. Are there areas of botanical interest, with

good field trip possibilities? Are there things to do

when sessions are over: good local restaurants,

cultural attractions, fun local flavor? Is there fresh

air? Breathing re-circulated air conditioning all day

is not good for anyone. Snowbird provided

opportunities for hiking and communing with nature.

Austin and Chicago had great night life. Chico,

Austin, and Madison offered small local restaurants

and good food.

The Future

We have currently booked venues for 2008 and

2009. Plans are already under way for Botany 2008

to meet at the campus of the University of British

Columbia with our traditional partners and the

Canadian Botanical Association/L’Association

Botanique du Canada, July 26 – 30, 2008

(

www.2008.botanyconference.org

). Much more

information will be coming soon!

Botany 2009 will be a return to Snowbird, July 25–

30, 2008. We’ll be back in the majestic mountains

of Utah, enjoying the great field trip possibilities and

the beauty of the area. From a meeting planner’s

perspective, Snowbird is appealing for many

reasons. They offered us great rates if we signed on

right after the Botany 2004 conference. They offer

enough meeting space to fit our needs and have

flexible housing opportunities. In addition to the

traditional hotel rooms, they have condo units that

can sleep up to 6 people and have kitchen facilities.

Groups of students are encouraged to take

advantage of these condos….or bring your family

and combine science and vacation.

Currently, I am searching for a site for Botany 2010.

It has been suggested that we go East. The Joint

Society program committee has charged me with

searching from Maine to Puerto Rico, so stay tuned

as I travel, search and report back to you.

As we go forward with our conferences we strive to

increase your satisfaction with our site choices. We

will continue to rotate around the country and

occasionally meet in Canada with our Canadian

partners—and who knows? Perhaps someday in

we will meet in Mexico or Latin America. Wherever

we end up, please know that a lot of thought,

research, investigation, and comparison has gone

into picking the best site for the conference. We will

continue to look for “deals” – affordability and value

in the costs we can control and careful consideration

of the direct costs to all attendees.

If you have any comments about this article or

suggestions of cities, convention centers or campus’

you would like us to consider for future Botany

meetings, please contact me:

johanne@botany.org

.

Your suggestions are always considered.

6

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

Experiences of a Local

Arrangement Committee for a

Large Scientific Conference

How many of us have gone to a scientific conference

unaware of the organization behind it? The

registration line flows smoothly, the program is well

organized, the abstract book clearly directs you to

the talks and posters you wish to see, the rooms are

appropriately sized and clearly marked with

schedules posted outside, the projection

equipment operates well with assistants to help

you, web access is provided to allow you to keep up

with communications that cannot be delayed, and

social events flow smoothly and provide

opportunities to meet colleagues in a relaxed

atmosphere to make and reinforce collaborations

and friendships. Ideally, the conference is

inexpensive, especially for students and post-

doctoral researchers. All these experiences provide

good memories and a successful conference.

Good conferences flow smoothly and are efficiently

organized, thanks to hundreds of coordinated

decisions made over at least two years of conference

planning. In addition, the hosting of a conference

often requires considerable financial backing raised

from conference leaders or their academic

programs or departments. The planning of a

scientific conference, while personally and

professionally satisfying, entails more work,

responsibility, and potential pitfalls than many

anticipate. The purpose of our paper is to convey the

experiences and insights we gained from organizing

the combined conference of the VI International

Solanaceae Conference, the Potato Association of

America, and the III International Solanaceae

Genomics Conference. Assistance in planning the

conference was obtained from websites and

personnel from prior Potato Association of America

(PAA) Local Arrangements Committees and

Solanaceae conferences. We hope this

documentation of our experiences will be useful for

future conference planners as many details were

not available to us from any other sources.

This paper details the challenges and opportunities

of organizing a scientific conference and to aid

future conference organizers. It arose from the

organization of the combined conference of the 90th

Annual Meeting of the Potato Association of America,

the VI International Solanaceae Conference, and

the III Solanaceae Genomics Conference of the

Solanaceae Genomics Network, held in Madison

Wisconsin from July 23-27, 2006. It was attended by

539 participants from 42 countries. The unifying

theme of these three groups was the science of the

Solanaceae. The theme of the Conference

Solanaceae: Genomics Meets Biodiversity,

described the goal of integrating all phases of

Solanaceae science with the emerging field of

genomics. This goal is fostered by the parallel DNA

sequencing efforts of both the tomato and potato

genomes.

Pre-Event Planning

Many decisions need to be made about conference

venue years in advance of a conference. First is

conference attendance estimate for the various oral

sessions. If an organization has a long history, then

predicting attendance numbers should be fairly

easy. If a conference is for a new organization or it

combines several organizations, then attendance

would be more difficult to predict. Despite the

importance of this decision you can only make a

rough guess about actual attendance.

Decisions need to be coordinated with Conference

leaders well in advance. The initial critical decisions

that must be made by a local arrangements

committee (LAC) of a large scientific conference are

the choice of venue and conference dates. The

conference should be held in a city that is easily

accessible by air. For example, locations with service

by regional airlines or only a few flights per day will

limit participants to those who make early travel

arrangements. The location must have adequate

convention facilities appropriate for the size of the

conference. Most commonly, conferences are held

at large hotels that have their own meeting rooms

and staff that can help with conference planning. A

conference date must be chosen to minimize

conflicts with other professional meetings likely to

be attended by potential participants. Early

announcement of the conference help other

organizations to schedule meetings with minimal

conflicts as well.

Hotel accessibility is important to consider when

choosing a conference site. Ideally the conference

hotel will have reasonable room rates and enough

rooms for all participants. If additional rooms are

needed, hotel options should be available within

walking distance and with a range of rates to suit the

needs of diverse participants with different travel

budgets. For the convenience of both the LAC and

participants, host hotels should offer complimentary

airport shuttle service. In addition, most participants

will not have their own transportation so the venue

should be within walking distance of a shopping

district with a number of restaurant options. The

LAC should visit potential hotels and meet with

hotel staff before making a final decision about the

conference site. The selected hotel(s) should be

appealing, clean, and provide modern amenities,

such as free high-speed internet access.

The LAC should learn specifics about how hotel

contracts are written when meeting with staff. We

7

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

.

encountered two types of contracts. Our host hotel

contract contained a “contingency clause” that

required reservation of a number of rooms for each

night of the conference. The LAC was financially

responsible for any rooms that were not booked by

conference participants. Reserving enough rooms

for all participants that wanted to stay at the host

hotel had to be balanced with the financial risk of

overestimating the number of rooms necessary.

The second type of contract encountered reserved

rooms until one month before the conference. These

hotels were less expensive than the host hotel, but

were farther from the conference site. We did not

know during early planning whether the majority of

participants would pay the higher room rate of the

host hotel for the convenience of staying at the

conference site, but the majority of the attendees

payed a higher room rate in order to stay at the host

hotel.

Because the LAC members for this conference

were scientists and not professional meeting

organizers, it was important to the committee to

hire, at a reasonable cost, professional conference

planners. A LAC should interview several conference

planners to make sure they have experience

planning scientific conferences, a successful track

record, and enthusiastic recommendations from

previous clients. The Monona Terrace staff was the

venue planning resource for this conference, and

was thus familiar with the attractions and limitations

of the facility and could offer several options for each

conference’s needs. Hotel staff can also provide

guidance on meeting room requirements, audio-

visual (AV) equipment, and catering needs. Although

facility personnel were critical for providing logistics

expertise for this conference, they do not typically

have enough experience with scientific meetings to

help with the scheduling of talks, the preparation of

the program book, or the publication of conference

proceedings. The Botanical Society of America (BSA)

managed the registration and finances for the

conference.

Social events were critical for the Solanaceae

conference success by providing relief from the

intensity of scientific presentations, opportunities

to forge and maintain collaborations, keeping the

group together outside of meeting sessions, and

making the conference memorable. PAA

conferences traditionally maintain membership,

meeting attendance, and a sense of community

because of well planned social programs, including

an accompanying persons program and a

formalized final banquet and awards program. Social

events for this conference were an opening evening

reception, an evening wine-and-snack poster-

viewing social, an evening cookout, and a closing

evening awards banquet. In addition, full hot

breakfasts, lunches, and morning and afternoon

breaks kept the group together between sessions,

and we provided a full-day mid-conference tour of

local sites for accompanying persons. In addition,

we set up at a desk at the convention center to

provide tour ideas, maps, brochures, bus

schedules, and information about local attractions.

Fundraising

Fundraising is critical to keep costs low yet provide

a quality conference. The PAA and the Solanaceae

Genomics Network have a wide number of

multinational, regional, and local industries that

participate in the conference and serve as potential

donors, and the fundraising committee included

members committed to hosting the conference and

familiar with the societies represented and as well

as allied industries. It was critical to identify

“connected” fundraisers with good reputations

through extension or other outreach programs to

solicit funds from potential industry donors.

A good conference program attracts participants

and registrants. This was especially evident during

our fundraising campaign, as some contributors

donated funds only after they reviewed the program.

Our meeting had a joint half-day opening plenary

session, and thereafter the PAA and combined

Solanaceae groups met separately. The Solanaceae

groups have a large concentration of scientists in

South America and many there wished to attend but

could not afford the travel costs. An awards

committee provided grants to aid attendance.

Our first fundraising step was to identify potential

sponsors that included 1) industries and entities

that annually sponsor the PAA conference, 2)

industries and entities that are related to

Solanaceous crops, 3) biotechnology and

agrochemical companies, and 4) scientific granting

agencies. We identified potential sponsors by

consulting prior contributors to the PAA and the

Plant and Animal Genome Conferences, as well as

local grower associations who provided lists of

associate members. We also searched the web for

biotechnology companies. The large focus on

genomics of Solanaceous crops dramatically

increased the list of potential sponsors as many

companies market products used in genomics

research, sell genetic resources of solanaceous

crops (seeds), or have a direct interest in the

marketing of solanaceous crops other than potato.

In total, we contacted more than 150 companies,

and raised 112,000 from 36 donors. First contact

was made by writing letters to collaborators or

known contacts of companies familiar to the

fundraising committee. For companies for which

the fundraising committee had no contacts, letters

were written to the presidents or marketing directors.

Contacts were made two years before the

conference because some companies plan funding

8

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

cycles and set budgets years in advance. In addition,

fiscal years vary by company and range from January

to December, requiring budgets be set 12 to 18

months in advance of the conference. Follow-up

letters were sent to identify contacts within each

company 12 to 14 months prior to the conference

to provide information about the conference, identify

dates, and solicit their potential support. Follow-up

contacts were made repeatedly in person 12 to 6

months prior to the conference to continually remind

key sponsors about the upcoming meeting.

Approximately six months before the conference,

each contact was called again and asked for a firm

funding commitment. This process— which, in all,

required hundreds of hours—continued until the

final weeks before the conference.

Budget Planning

Building the budget was one of the most important

and frustratingly difficult aspects of the conference,

because there were many unknowns. The most

critical variables were the number of registrants,

fundraising success, and unfilled rooms from hotel

contracts. As conference organizers, we did not

anticipate being personally responsible for financial

obligations with hotel contracts. The PAA was the

only one of the three groups with a formalized

organizational structure and it had an endowment

and a budget. However, the PAA did not take any

financial responsibility for conference expenses,

placing that burden on the LAC. There were many

sleepless nights tracking registration numbers,

raising funds, fundraising, and contemplating

possible catastrophes that could stop the

conference (e.g., SARS, Bird Flu, Mumps (there

was an epidemic in adjacent Iowa), stringent visa

restrictions, terrorism,).

The LAC had to balance the need to keep registration

expenses low (especially for students and post-

docs) with the need to cover conference costs.

Budget planning was one of the first steps in

planning the conference. It required several key

steps. First, the fundraising committee needed to

be familiar with each of the organizations in order

to know what was expected by each group and its

attendees. For example, complimentary lunches

are traditionally a part of the PAA conference. In

addition, the PAA plans multiple business meetings

that require food. Without being familiar with the

PAA, there would be no way to plan for the resources

necessary to host a successful conference. Next,

a list of the budgeted items was created to identify

expected costs. Numerous ancillary expenditures

arose at multiple points along the conference

planning process, but large budget categories had

to be identified up-front for overall planning. The

PAA provided budgetary information on its website,

and we interviewed prior conference LACs of the

PAA and Solanaceae Conferences to identify key

and unexpected expenses. A potential huge cost

was hotel contingency contracts, which stipulated

reimbursement for unbooked rooms. After identifying

the conference venue, we could obtain estimates

for all key items such as catering, audiovisual, and

venue costs. The final step was to estimate

conference attendance. By estimating conference

attendance and predicting total costs of the

conference, we could set registration fees as well

as fundraising goals necessary to support the

conference.

Publicity

Advertising the conference was critical. The PAA

and the Solanaceae Genomics Network have

organized communication structures with e-mail

lists, newsletters, and web resources so

advertisement was relatively easy. To advertise the

conference, we relied on e-mail lists from the

Solanaceae conference in Nijmegen, the

Netherlands, in 2000; the Solanaceae Genomics

Network; the Ischia Italy 2005 conference; the PAA;

and the Lat-SOL Network. We gathered e-mail

addresses from 1050 participants who gave papers

at the conference, and this list will be available to

future conference organizers. Various conference

leaders further advertised the conference with poster

and oral announcements at the Solanaceae section

of the Plant and Animal Genome Conference, the

business meetings of the American Society of Plant

Taxonomists, the Sociedad Argentina de Botánica,

the International Botanical Conference, the Botanical

Society of America, the Solanaceae Genomics

Conferences, and the PAA annual conference. We

also advertised through newsletters or through the

Eucarpia Conferences website, , the International

Coffee Genome Network, Lat-SOL, Red

Latinoamericana de Botánica, the Crop Science

Society of America, the Red Latinoamericana de

Botánica, the Society for Economic Botany, the United

States Department of Agriculture, Cooperative State

Research, Education, and Extension Service,

CSREES Plant Sciences Update, and the University

of Wisconsin Department of Horticulture , and in

Global Potato News, Taxon, the Botanical Society of

America Plant Science Bulletin, The Solanaceae

Newsletter, The World of Food.

All five prior Solanaceae Conferences had published

proceedings, and we initially had an oral agreement

with a publisher for the 2006 conference. This

agreement became much more complex as

negotiations advanced. Considerable time was

necessary to work with this publisher and at the end

we were not given a contract but rather only a

promise to consider the manuscripts after an all

peer-reviewed copy was submitted. Fortunately,

Acta Horticulturae, an experienced publisher of

horticultural conferences, actively sought to publish

the proceedings from this conference and based on

9

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

experiences to date we recommend them as

publisher for other conference proceedings.

Meeting Planning

Meeting Rooms

The meeting room size must match attendance. If

a room is too small, then some people have to

stand, and if too big, then a speaker is talking to a

half-empty room. Room configurations can be used

to adjust the room capacity. With theater-style

seating, rows of chairs are placed in the room. This

allows for the largest seating capacity, but required

audience members to take notes on their laps.

Classroom seating places a row of tables in front

of every row of chairs. During the Solanaceae

conference, the configuration of rooms at the

conference center gave us the option of enlarging

a room if necessary. For each of the PAA concurrent

sessions, we reserved an extra, adjoining meeting

room, allowing us the opportunity to remove a wall

to double the size of each room if necessary. The

PAA Breeding and Genetics section meetings

required this option due to a larger than average

attendance, presumably because of participation

by the other two groups.

A simple amenity appreciated by participants was

a set of tables and chairs made available throughout

the week in the large open area used for breaks.

This provided participants with a relaxed and

comfortable setting in which to continue

conversations initiated during the breaks.

Audio-visual equipment

Audio-visual (AV) equipment can make or break the

scientific portion of a conference. We chose to use

the highest quality projection equipment available

(large screens and high-resolution projectors) so

equipment would not stand in the way of

presentations. A wireless microphone and

computer mouse in each room allowed speakers

to be mobile during their presentations. In the large

presentation room, we placed microphones

throughout the room so that the audience could use

them to ask the speakers questions. We rented a

“speaker-ready” room with several computers,

allowing presenters to review each slide and

download their PowerPoint files to a central server.

Then, when giving a presentation, the speaker

simply loaded the file from the server with the

assurance it would look exactly as it did in the

speaker-ready room. We required speakers to

format presentations as PowerPoint files on a PC-

based platform. This avoided technical problems

associated with maneuvering across file formats

and platforms. In addition to the speaker-ready

room, we provided a small room with a projector

and computer, allowing speakers to practice.

Speaker podiums and microphones were rented

for receptions, banquets, and other social events.

We also provided a set of six computers with Internet

access and a printer for checking e-mail during the

conference. This was important for members of

various committees who needed to write and print

reports during the conference. In addition free, high-

speed wireless Internet was provided throughout

the conference site.

Catering

The hotel or conference site staff was able to

provide advice regarding catering needs. We chose

to provide a hot breakfast and lunch for participants.

The lunch was especially important to keep the

afternoon scientific meeting on schedule, and the

breakfast helped keep the participants together as

a group throughout the day. It is also important to

provide refreshments during the morning and

afternoon breaks. Late registrations can create a

problem for catering estimates. We provided a

head count for each meal approximately one week

prior to the conference. The Monona Terrace

automatically planned for 5% more guests than

requested, so a few last minute additions were not

a problem. We told participants that they might not

be provided with meals if they registered less than

a week before the conference. However, we were

able to renegotiate food service contracts for 42 late

registrants. Finally, special meal requests need to

be available on the registration form so that

vegetarian and other specific nutritional needs can

be met.

Registration and Staffing

While the human resources required for planning

a conference are large, so are the resources for

running the conference itself. The registration desk

was continuously staffed by two to three people,

with one person adept at web registrations. We flew

a staff member from the registration company, the

Botanical Society of America, to our conference for

this purpose. Additional staff members were added

during expected busy times such as Sunday

afternoon and Monday morning. AV/computer

experts were hired from the Monona Terrace to work

full-time throughout the conference to handle

potential problems such as computer access to the

network and microphone feedback. One was

stationed in the large Solanaceae meeting room,

while another worked among the three smaller PAA

rooms. In addition, we hired and trained students to

work in the speaker-ready room and to act as

projectionists in each of the three PAA rooms.

Colleagues were recruited to serve as session

moderators. The Monona Terrace provided us with

hand-held radios so LAC members could keep in

contact with each other and with the Monona Terrace

staff.

Poster sessions were relatively easy to organize.

An early deadline for poster submissions provided

10

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

the time necessary to determine the size of the room

needed for the poster session and the number of

poster boards needed. The Monona Terrace

provided the poster boards for our conference, but

local companies were also capable of supplying

the boards. We tried to group the posters into logical

categories so that those with similar topics would

be together. We organized a wine-and-cheese

social event to encourage participation and

enjoyment of the poster session.

Many details are needed to organize a conference.

Potential and actual participants need to be kept

informed of deadlines and costs for early and late

registration, hotel availability and booking dates for

reduced costs, local logistics, social and scientific

events, opportunities to speak and give posters,

media format, times for talks and posters, visa

requirements, and Internet access. The large e-

mail list for advertising was trimmed to a list of

conference attendees to communicate information

to abstract authors and registrants.

This was the first year the PAA utilized web

registrations and abstract submissions, requiring

considerable adjustment by members accustomed

to postal mail submissions. However, there were

so many cost and time-saving advantages to web

registration and abstract submission that we had to

rely on this system exclusively. A contract was

initially signed with a company to take on-line

abstracts and registrations, but they performed

poorly. We cancelled their contract at a cost of $1200

for their initial work. We ultimately used BSA, which

took on-line abstracts, registrations, and published

the abstract book with their in-house proprietary

software and organizational staff. This system was

highly integrated and allowed multiple options to

view and query the program. In addition, in-house

publishing by the BSA was efficient and cost-effective.

The BSA saved us considerable time and produced

high-quality copy, and we recommend them highly.

Some attendees were taxonomists who used this

opportunity to visit local herbaria. Special access

hours were needed at the University of Wisconsin-

Madison herbaria on evenings and weekends for

this service. We took every opportunity to

acknowledge everyone who aided in the conference

on the web, in the abstract book, and in this article.

An effective committee structure was important.

The PAA and Solanaceae groups had separate

program committees. However, good

communications were necessary with each

program committee and the BSA to coordinate

abstract submissions, plan rooms, and print the

program. Other committee responsibilities were

lodging to include a primary conference hotel,

signage at the conference, tours and events, visas,

grants and fundraising, a local and an accompanying

persons committee, and invitation of dignitaries to

address the opening session.

Other Lessons Learned

1. The 5%/95% rule. No matter how hard you try to

make registration, abstract submission, hotel

options, and other details clear to your participants,

a small minority of your attendees (5%) will require

huge amounts of your time (95%). The LAC was

responsible for clearly written directions for the

many tasks of the conference, but many people are

very busy, do not read directions, and attempt to

perform all on-line tasks intuitively. Tremendous

time was needed to write back to registrants and get

them to correct abstract or informational errors.

Many simply did not respond, leaving committee

members with the task of researching and filling in

necessary data. Some special requests were

encountered including sending registration detail

and abstracts by email and transcription to online

forms, sending registration money by wire transfer,

making hotel reservations, pick up from the airport

even though all local hotels provided free shuttles,

or securing foreign-language speaking babysitters.

We tried to meet all requests for two reasons. First,

we needed a critical mass of registrants to meet our

fixed costs (accurate, actual attendance was

impossible to predict). Second, we realized that

what appeared to us to be an unreasonable request

could be caused by our failure to communicate

clearly, special needs, unfamiliarity with the web or

browser incompatibilities, cultural differences, or

other problems. Ultimately, our primary goal was a

positive meeting experience for all in attendance.

2. Time commitments. We tried to maintain a

quality conference in the premiere conference venue

in Madison at a reasonable cost. The venue

expenses were considerable, so we tried to

compensate by performing as many organizational

tasks ourselves as possible to save costs. This

included raising funds to keep registration fees

(including food and social events) as low as possible.

Using this model, planning for the conference proved

to be an 80% time commitment for the chair of the

LAC for 12 months preceding the conference, and

40% of the LAC chair’s time the year before that. In

addition, two other LAC members (Bussan, Jansky)

spent 15% of their time committed toward the

conference as the date approached. The other LAC

members donated additional time, in addition to

time spent by the abstract submission and

registration company (BSA) and the program

directors.

3. Conference updates. Conference updates were

crucial to communicate developments to all

registrants, especially reminders of deadlines for

11

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

early registrations and cutoff dates for conference

event sign-ups, hotel reservations, etc. Eighty

percent or more of abstracts and registrations were

submitted in the few days immediately preceding

deadlines. Deadlines were advertised three

months, three weeks, and one week before cutoff

dates. Registration income was critical to running

the conference and local organizers were concerned

to and beyond the conference if the conference was

solvent. However, late registrations were common.

About 15 registrants cancelled and required refunds

and there were 70 late registrants.

4. Announcements. The opening reception and the

plenary session was our only opportunity to speak

to the entire set of attendees. This time was used

to make general announcements, such as meals,

when and where ticketed events were to take place,

and where breaks were to be held. Announcements

were necessary throughout the week requiring a

strategy for getting information to all attendees.

Bulletin boards, notices posted at the registration

desk, emails to the participant list, and verbal

announcements during the sessions were used to

communicate announcements. At the opening

reception, attendees were alerted about where to

locate.

5. Ticketed Events. Be sure to anticipate last-

minute requests for ticketed events. We had people

request banquet tickets an hour before the banquet.

Constant communication was necessary with the

caterer and the absolute deadline for a head count

at each event was needed. This deadline must be

communicated effectively to conference participants.

In addition, we had several people ask for refunds

for ticketed events. Be prepared for those requests

by determining in advance whether they will be

granted. Also, try to anticipate creative solutions that

may be offered by attendees. For example, one

person could not attend a tour and asked whether

the tour ticket could be substituted for a banquet

ticket.

Many participants required certificates of attendance,

and we spent considerable time at the registration

desk typing these individually. Make a standard

attendance certificate on official letterhead where

you can write in the name of the person and a place

to sign.

Personal and Professional Benefits Of Being A

Conference Organizer

Conference organization was such a time-

consuming task that it was often difficult to get

volunteers. Few take on such a task a second time.

The purpose of our paper is to provide future

conference organizers practical experiences

including possible pitfalls and lessons learned to

aid them in their planning, not to discourage

volunteers. We are glad we took on this task as it

was personally and professionally rewarding.

Service to your community is expected and assuming

that you organize a good conference and serve your

registrants effectively and with respect, you have an

opportunity to highlight your institution and city well,

and gain recognition from your peers. You interact

with hundreds of people, and initiate collaborations

and friendships.

You learn how to communicate much more

effectively. Repeated requests from “difficult people”

who could not seem to follow directions often

showed us that we were at fault through poor

communication or cross-cultural

miscommunications. We gained an appreciation

of others’ special needs, especially the financial

difficulties of participants from underdeveloped

countries. Finally, we learned to see conferences

and volunteers in an entirely new light through the

huge effort needed for the tasks involved. We

recommend these tasks to anyone assuming you

have access to good facilities and willing

collaborators, and enjoy working with others.

Spooner, D.M., S.H. Jansky, and A.J. Bussan. 2007.

Experiences of a local arrangement committee for

a large scientific conference. Acta. Hort. 745: 513-

532.

The full version of this paper is available from

http:/

/www.horticulture.wisc.edu/faculty/faculty_pages/

Spooner/spooner.php.

David M. Spooner and Shelley Jansky

USDA, Agricultural Research Service

Department of Horticulture

University of Wisconsin

1575 Linden Drive

Madison, Wisconsin, 53706-1590 U.S.A.

Alvin J. Bussan

Department of Horticulture

University of Wisconsin

1575 Linden Drive

Madison, Wisconsin, 53706-1590 U.S.A.

12

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

The Three C’s: Early Botanical

Leaders at the University of

Chicago

There was a University of Chicago (1858-1886)

before the present one. It was non-sectarian

although founded, and mostly financed, by wealthy

Chicago Baptist business and community leaders.

Funding was never adequate, however, and

continued borrowing, along with local (Chicago fire

of 1871) and national (financial depressions, Civil

War) disasters eventually forced it to close after 28

years.

Baptist leaders immediately began soliciting

prospective donors for a new University. They were

able to interest the richest Baptist in the nation, John

D. Rockefeller. His several contributions eventually

totaled $10.5 million, a phenomenal sum for that

time, which ensured financial stability and funds to

attract a first class cadre of faculty members. The

site of the new University of Chicago, also non-

sectarian, was determined by a donation of 10

acres of mostly swampy land in the village of Hyde

Park, a suburb (soon annexed) immediately

southeast of Chicago that fronted on Lake Michigan.

Additional acres were purchased, construction

proceeded apace, and the first students entered in

October of 1892, chanting praise to Mr. Rockefeller

(“Hooray for John D., he gave all his loose change

to the U.of C.!) as they passed through the portals.

A School of Biology was part of the original 1892

academic plan, but it soon proved to be unwieldy,

and in1894 it was divided into six Biology

departments. One of these was Botany, although

it had neither a permanent home nor a faculty except

for one part-time instructor (John Coulter). Within

four years, however, Botany would include among

its small faculty three people who would be largely

responsible for the university’s national and

international botanical reputation during its first four

decades. By coincidence, all three had surnames

beginning with C, hence the “Three C’s” of the title.

Before describing their accomplishments, the

fortunate event that provided a home for Botany

should be mentioned.

In 1895 Miss Helen Culver, a wealthy Chicagoan,

contributed slightly more than one million dollars to

construct a Biology quadrangle delimited by four

buildings designed to provide permanent quarters

for departments split from the original School of

Biology. She named the quadrangle for her cousin

Charles J. Hull, a trustee of the first U of C, but who

is best remembered today because his Chicago

mansion became Jane Addams’ Hull House. Thus

in 1897 Botany gained an elegant home, the three-

storied Hull Botanical Laboratory, complete with

rooftop greenhouse.

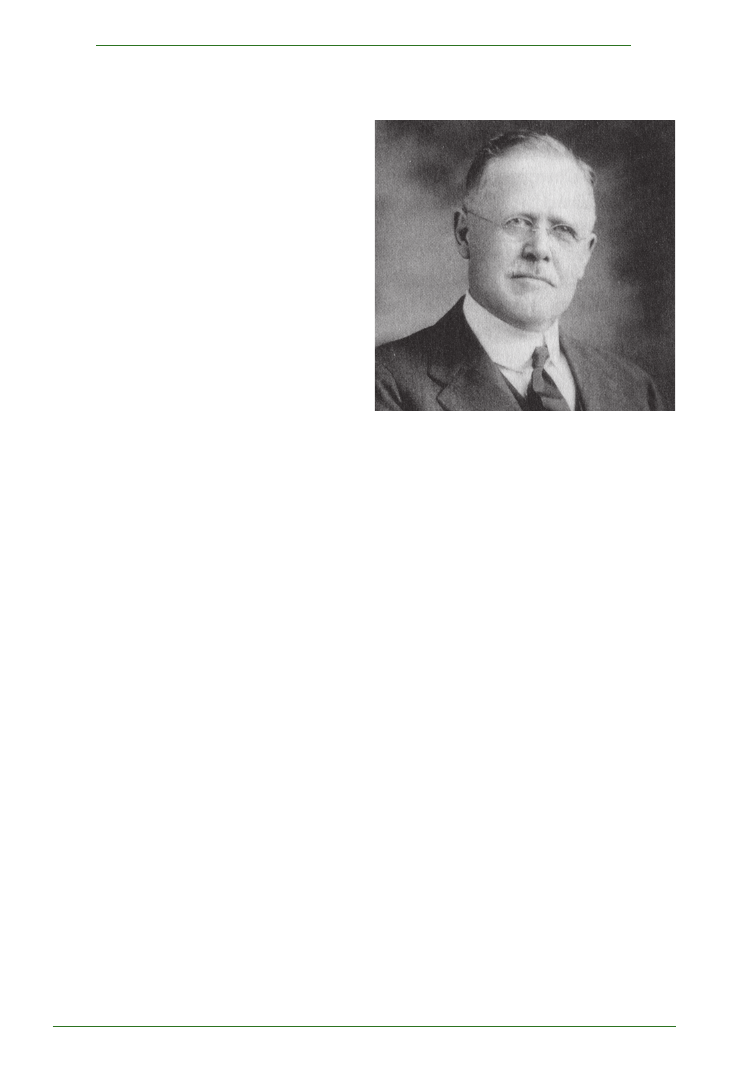

The first “C”: John Merle Coulter (1851-1928)

Coulter was born in China of missionary parents,

but his father died shortly after John’s birth, and his

widow moved back to her home state of Indiana to

raise John and his brother. In due course Coulter

attended nearby Hanover College, later served on

its faculty, and later at Wabash College, also in

Indiana. By the early 1870’s he was also doing

graduate work at Harvard University. Through his

Harvard connection, he was chosen to be assistant

Geologist on the important 1870’s Hayden Survey

of the Yellowstone region of the western USA. In the

field his superior botanical expertise was soon

recognized, and he was appointed as the Survey’s

Botanist. His Hayden experience and the plant

specimens collected during it contributed much to

the floristic studies Coulter concentrated on early in

his career.

Coulter returned afterwards to Wabash college,

where he founded the Biological Bulletin in 1875,

which he renamed Botanical Gazette in 1876. He

also acquired a PhD from Harvard. In the late 1870s

and during the 1880s, while still at Wabash, he

published floristic and monographic works, a phase

of his career capped in 1890 by his co-authorship

(with Serena Watson) of the 6

th

edition of Gray’s

Manual of Botany of eastern North America.

In the 1890’s Coulter’s interests shifted toward

morphology and evolution (he became a lifelong

strong advocate for Darwinian evolution), and his

reputation grew as a dynamic teacher and speaker.

He was appointed President of Indiana University

in 1891 at age 40. In 1893, however, he left to

13

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

become President of the much smaller Lake Forest

College, just north of Chicago, because its governing

board convinced him that Lake Forest intended to

become the “Great University” of the Chicago region.

The plan was greatly exaggerated, as he soon

realized, but he stayed as President until 1896.

During his time at Lake Forest he did something

unusual for a college President. He commuted

south to the fledgling University of Chicago on

Saturdays to serve as the part-time sole instructor

in the new Department of Botany, 1894-96. His

Saturday lectures soon attracted scores of

enthusiastic students, two of whom would later

become the other “Cs.” It was inevitable that Coulter

would be asked to join the U of C full-time, and he

was appointed Head Professor of Botany in 1896,

a position he held for 29 years! The trajectory of his

career was truly unusual, perhaps even unique.

The highlights of Coulter’s career at U of C can be

presented most efficiently in outline form, including

only his major scholarly contributions while there.

It should be emphasized that throughout his career

he was in great demand as a dynamic teacher and

as a speaker before both professional and lay

audiences, and he was elected several times to

high office in professional organizations. His most

important scholarly endeavors while at U of C were

co-authorships with the other two “Cs”, as indicated

in the following career outline.

1894-96—Part-time lecturer as sole Botany

department faculty member

1896—Appointed Head Professor, U of C Botany

department

1896-97—Elected President of the first Botanical

Society of America

1901—Led the unsuccessful first attempt to

preserve 1500 acres of Indiana Dunes as a

U of C Biological Station.

1901—Book: “Morphology of Spermatophytes” co-

authored with Chamberlain

1903—Book: “Morphology of Angiosperms” co-

authored with Chamberlain

(Includes 250-page first synthesis of what

is now called angiosperm embryology)

1909—Elected to membership in the National

Academy of Science

1910—Book: “Morphology of Gymnosperms” co-

authored with Chamberlain

(Revised and co-authored second edition

published in 1917)

1910-11—Book: “Textbook of Botany for Colleges

and Universities”

(Co-authored with Cowles and Barnes;

the leading Botany text for many years)

1915-1921—Served as President of the Chicago

Academy of Sciences

1916—Elected President of the present Botanical

Society of America

1918—Elected President, American Association of

University Professors

1922—Appointed Chief Scientific Advisor of newly

founded Boyce Thompson Institute

(He attempted, unsuccessfully, to locate it

at U of C)

1925—Retired as Head of U of C Botany Dept. after

29 years, but remained on faculty

1927—Retired from U of C, moved to New York to

Boyce Thompson Institute

(Served as Chief Scientific Advisor)

1928—Died of a heart attack

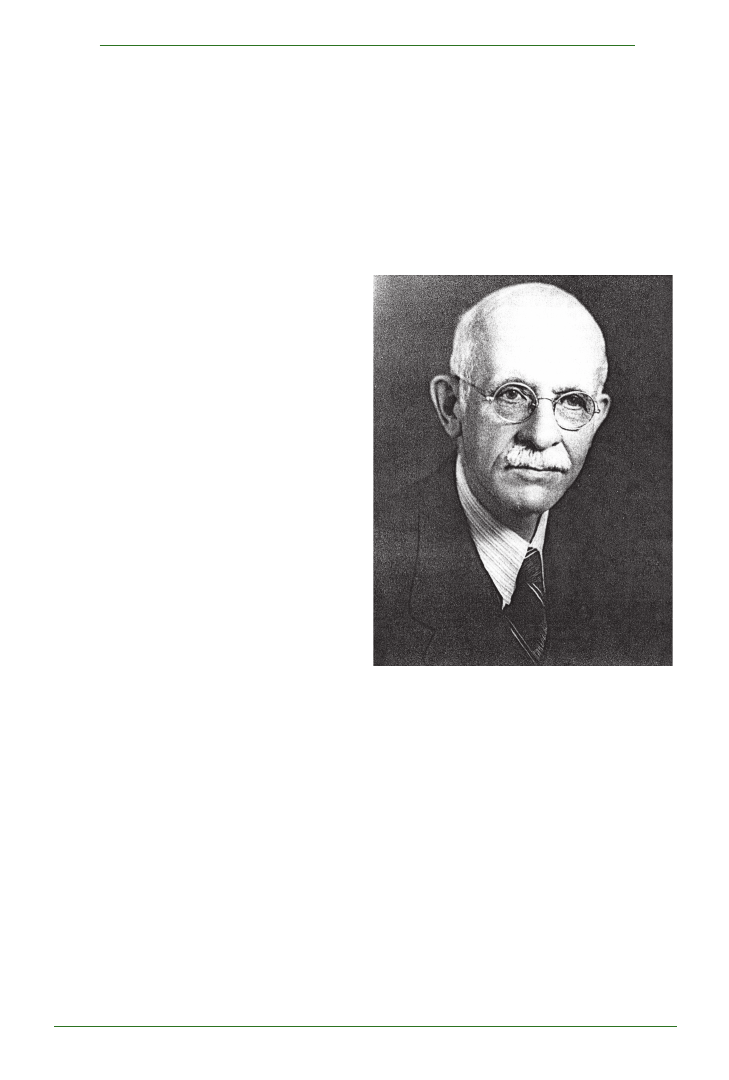

The second “C”: Charles Joseph Chamberlain

(1863-1943)

Chamberlain was born and raised in Ohio, where

he attended Oberlin College. After graduation he

became a high school teacher, and later a high

school Principal, in Minnesota. He did return to

Oberlin during summers, where he taught Zoology,

and earned a Master’s degree. He enrolled as a

PhD student at the new U of C in 1893, intending to

pursue work in zoological microtechnique and

histology, but after attending Botany lectures by the

charismatic Coulter, he switched to Botany and did

his dissertation research on the embryology of

Salix. In 1897 he received the first PhD in Botany at

U of C and was immediately appointed to the

teaching staff, in charge of laboratory instruction.

His subsequent published work on embryology,

gymnosperms, and botanical microtechnique set

the standards for those disciplines for decades. A

brief outline of his career highlights follows.

14

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

1893-1897—Graduate student in Botany at U of C

1897—Received first PhD in Botany at U of C, and

appointed to Botany faculty

1901—Book: “Morphology of Spermatophytes” co-

authored with Coulter

1901—Book: “Methods in Plant Histology”, revised

five times, last edition in 1932

(This was the standard work for almost 40

years)

1901-1902—A research year spent with Eduard

Strasburger in Germany

1903—Book: “Morphology of Angiosperms” co-

authored with Coulter

(Includes 250 page book-within-a book

first synthesis of angiosperm embryology)

1910—Book: “Morphology of Gymnosperms” co-

authored with Coulter

(The standard work, revised by them in

1917, and by Chamberlain alone in 1935)

1904-1917—Made several trips globally to study

and collect cycads

(Assembled the world’s largest living cycad

collection in a U of C greenhouse)

1919—Book: “The living cycads” about his travels

and observations on cycads

1927-1941—taught summers and semesters at

US Biological Stations and Universities

1929—retired from U of C at age 66 but remained

professionally active

1930—Book: “Elements of plant science,” a general

botany textbook

1931—Elected President of the Botanical Society of

America

1935—Book: “Gymnosperms, structure and

evolution”

(A thoroughly rewritten edition of

Chamberlain and Coulter’s 1917 edition)

1943—Died of a heart attack

(Left behind unpublished monograph of

cycads)

The third “C”: Henry Chandler Cowles (1869-

1939)

Cowles was born and raised in Connecticut. He

attended Oberlin College in Ohio, developed

interests in both Botany and Geology, and became

acquainted with Chamberlain when the latter came

back to Oberlin to teach summer courses. After

graduation, Cowles taught Biology at Gates College

in Nebraska for one year, then accepted a graduate

fellowship at U of C in 1895 to study ice age geology

and plant fossils. Like Chamberlain, Cowles

attended Coulter’s Botany lectures, which at that

time included an enthusiastic discussion of

Warming’s recent book on Ecology. Cowles was

influenced by Coulter to switch his research to a

study of plant communities in relation to the dynamic

physiography of the nearby Indiana Dunes along

the south end of Lake Michigan. In 1898 his PhD

dissertation: “An ecological study of the sand dune

flora of Northern Indiana,” followed by three major

papers published from it during 1899-1901,

established the principles of physiographic ecology

and ecological plant succession tending toward

climax formation. This work established his national

and international reputation early on, and he

continued to study dunes around the world

throughout his career. His important achievements

are outlined as follows.

1898—Received PhD, U of C, and appointed to U of

C Botany department faculty

1898-1901-—Published three influential papers

on dune ecology from his dissertation

1901 et seq—Advocated, helped found County

Forest Preserves, State Parks in Illinois

1901 to 1930’s—visited dune formations world-

wide on many field expeditions

1904-06—3-volume tome: “Geology” co-authored

with two U of C geology professors

1910-11—Book: “Textbook of botany for colleges

and universities” co-authored with

Coulter, and Barnes (U of C Botanist); the

leading text for many years

1913—Organized and led 10 European ecologists

on extended International

Phytogeographic excursion coast to coast

from July to October

1914—One of the founders of Ecological Society of

America; elected secy-treasurer

1916—Organized movement to create an Indiana

Dunes National Park

(World War I postponed action; Indiana

created a state park there in 1925)

1917—Elected President of the Ecological Society

of America

1922—Elected President of the Botanical Society of

America

1925—Became Chairman of U of C Botany

Department, succeeding Coulter

15

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

1934—Retired, age 65, due to Parkinson’s disease

1935—A Special Issue of the journal Ecology

dedicated to Cowles

1939—Cowles dies of complications of

Parkinson’s disease

Final thoughts

The U of C Botany department never had a large

faculty, but an extraordinary number of graduate

students passed through it (more than 300) during

the careers of the three Cs, in less than four decades.

Many of these students later became Botanists of

note during their own careers. It is also noteworthy

that each of the three C’s served as President of the

Botanical Society of America (1896, 1916, 1922,

1931). A 1982 book on the history and establishment

of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore says that

U of C botanists were instrumental in championing

preservation of the dunes as a national park. More

laudatory space could be devoted to each of these

individuals, but enough has been included here to

show that they led Botany at U of C through its early

glory days, decades during which it competed equally

with larger, long-established eastern University

Botany departments.

{Note: Adapted from a talk on the “Three C’s”

presented at a symposium on “Chicago Area

Botany” sponsored by the Historical Section of the

Botanical Society of America at its July, 2007 meeting

in Chicago.]

-Nels R. Lersten, professor emeritus, Department

of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology

(formerly Department of Botany), Iowa State

University, Ames, Iowa (BA, U of C, 1958; MS Botany,

U of C, 1960)

News from the Society

Picturing the Past

We are preparing a film detailing the history of the

Botanical Society of America, which will be available

online via the BSA website when finished. In

preparation for making this film, we are gathering

electronic images of all past presidents. We have

managed to locate pictures for most of the BSA

presidents. However, we still lack images for

Byron D. Halstead 1900

F. C. Newcombe 1917

G. J. Peirce 1932

John Buchholz 1941

Ivey F. Lewis 1949

Oswald Tippo 1955

We are asking all of the BSA membership to search

their files for images of these individuals and to

pass them on to us, either as prints or electronic

files. Naturally, we will return prints once they have

been scanned and we will happily acknowledge the

source of each.

Please send your images or electronic files to

Karl J. Niklas

or

Edward D. Cobb

kjn2 @ cornell.edu

ec38 @ cornell.edu

Department of Plant Biology

Cornell University

Ithaca NY 14853 (USA)

Report from the Office

As Dr. Sundberg pointed out early in the Bulletin, in

2007 the BSA had a pretty good year. Our overall

member numbers reached a new high since the

staff team began operations in St. Louis. I pleased

to report that by the end of the year we had 2,969

members (2,222 just a few years ago). More

importantly, student memberships over the same

period went from 359 to 715. Students are taking on

important roles throughout the BSA. This bodes

well for botany, the plant sciences, and for the

Botanical Society of America.

Accompanying this growth, we trust you’ll have

seen a number of positive changes in recent times.

If you’ve had the pleasure of submitting a manuscript

to the American Journal of Botany, we are pleased

to report this process just became easier! We have

moved to Aries’ “Editorial Manager” as a manuscript

submission system. We think you’ll find this a much

more user-friendly process.

16

Plant Science Bulletin 54(1) 2008

You will also notice another significant change – we

are continually working to reduce the time from

submission to decision, and the time from

acceptance to publication has been drastically

reduced. We are working with a much faster

production schedule—”eGalleys,” or page proofs

are generated within about 24 hours. And we have

further developments in process that will move

papers live online weeks ahead of print. This will

provide you with unprecedented timeliness when

publishing research.

Couple these new developments with your member

benefits to publish and we trust that if you are not

currently publishing in the AJB, you will want to do

so now!

Plant Science Bulletin itself is undergoing changes.

We are in the process of moving to a new format in

presenting PSB on the Society web site. As with the

AJB, a major consideration is to improve our ability

to provide timely information and better serve the

needs of the botanical/plant science community.

We’ve long been known for a speedy job and

research opportunity site and see this moving out

across all types of plant-related information normally

found in the Bulletin.