BULLETIN

FALL 2007

VOLUME 53

NUMBER 3

2@2

PLANT SCIENCE

ISSN 0032-0919

Editor: Marshall D. Sundberg

Department of Biological Sciences

Emporia State University

1200 Commercial Street, Emporia, KS 66801-5707

Telephone: 620-341-5605 Fax: 620-341-5607

Email: psb@botany.org

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

Landmarks and Milestones in American Plant Biology:The Cornell Connection .........................90

The Struggle for Botany Majors...................................................................................................102

News from the Annual Meeting

Forum Keynote Address:Naturally Right by Design: Bringing Learning and

School to Life................................................................................................................103

Vision and Change in Biology Undergraduate Education: A View for the 21

st

Century.....................................................................................................................105

Awards......................................................................................................................106

Scientific Literacy, Participation, and the BSA.........................................................109

News from the Society

BSA Science Education News and Notes..................................................................112

Editor’s Choice..........................................................................................114

A Model Elementary-level Plant Science Curriculum Based on ASPB’s

‘Plant Principles’......................................................................................115

Leaf Morphology Tutorial Web Site..........................................................116

Letter to the Editor, “What are you?”.......................................................................116

Announcements

in Memoriam

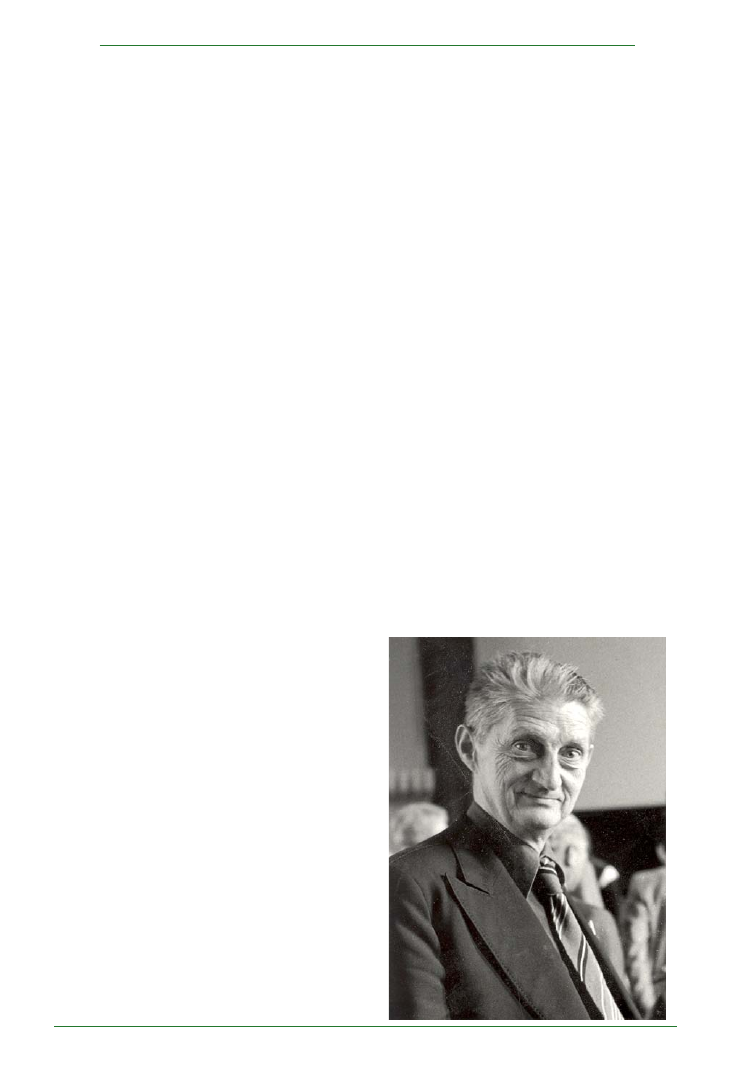

Robert Hegnauer (1919 - 2007).................................................................117

Personalia

Dr. Kayri Havens Appointed Director of Plant Science and Conservation

at Chicago Botanic Garden............................................................................118

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings

54

th

Annual Systematics Symposium: “Biodiversity and Conservation

in the Andes”.............................................................................................119

Positions Available

Conservation Scientist – Ecology and Curator of Native Habitats..............120

Award Opportunities

American Philosophical Society Research Programs....................................120

Harvard University Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research.......................121

Courses/Workshops

Investigating the Evolution of Plant Form....................................................122

The Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants...................................................123

Other News

Darwin’s Garden: An Evolutionary Adventure...........................................................124

Canadian Journal of Botany to be renamed Botany.....................................................125

North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation..............................126

Book Reviews

..............................................................................................................................127

Books Received

...........................................................................................................................134

Contact Information

...................................................................................................................135

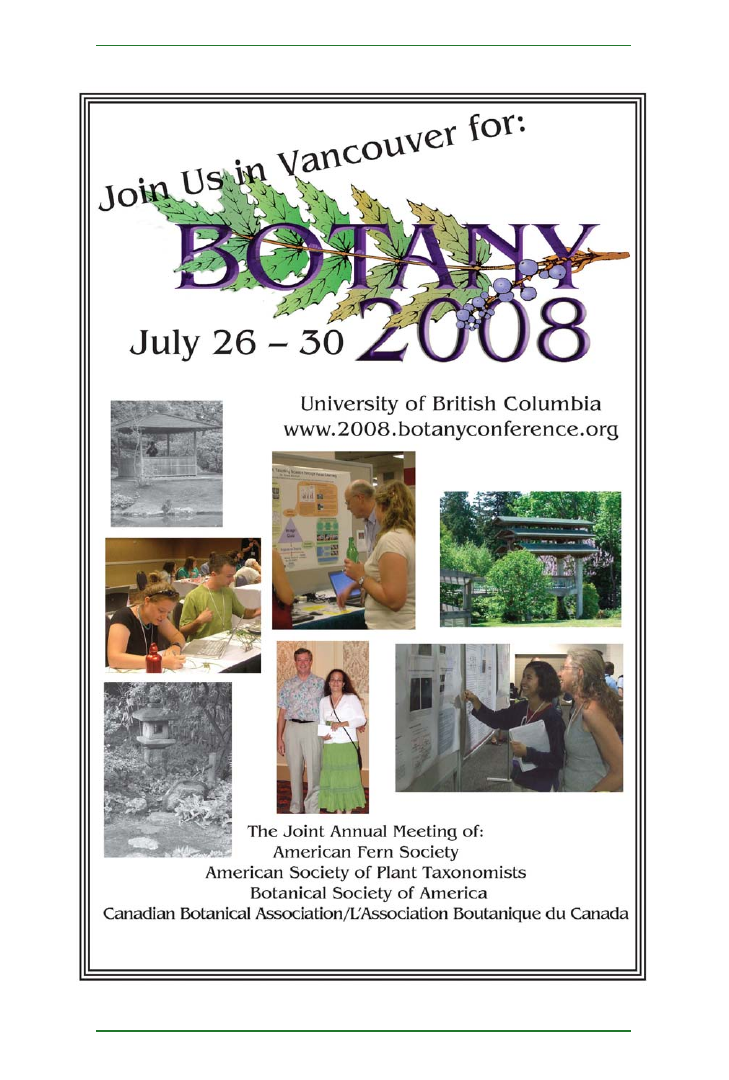

Botany 2008

.................................................................................................................................136

9 0

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Botanical Society of America

Business Office

P.O. Box 299

St. Louis, MO 63166-0299

E-mail: bsa-manager@botany.org

Address Editorial Matters (only) to:

Marsh Sundberg, Editor

Dept. Biol. Sci., Emporia State Univ.

1200 Commercial St.

Emporia, KS 66801-5057

Phone 620-341-5605

E-mail: psb@botany.org

ISSN 0032-0919

Published quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 4475 Castleman Avenue, St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299. The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of

the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Periodical postage paid at St. Louis,MO and additional

mailing office.

From July 7 through 11, Botany took Chicago by

storm with the biggest botanical event on the

continent since the St. Louis International Botanical

Congress eight years ago. It was also the first time

in three decades that the American Society of Plant

Physiologists (now Plant Biologists) met with the

Botanical Society. Many of the meeting highlights

and awards are summarized in the “News from the

Society” section.

The real highlights of this issue, however, are our

two feature articles. The first is a brief history of

botany at one of our premier institutions – Cornell

University. This is an expansion of the paper Lee

Kass gave last year at our Centennial Meeting in

Chico. I found it fascinating and asked Lee to share

her work with an article for Plant Science Bulletin.

What botany department would be better to feature

in these pages than the one that gave the Society its

first President, George F. Atkinson in 1907, and will

serve us with our next President (Karl J. Niklas,

President-elect, 2007) one hundred years later? In

addition to writing, revising, and re-revising this

article, Lee took the time to organize an excellent and

well-attended symposium on Botany in Chicago at

this year’s meeting. We hope to feature many of the

presentations from this symposium in future issues.

Our second article also features a premier botany

department. While the department of Botany and

Microbiology at the University of Oklahoma has not

had the same historical impact on Botany as Cornell,

in recent decades it has provided invaluable

leadership to the Society as we made the transition

to running independent meetings and creating a

professional business model. Wayne Elisens was

our program director (1997-1999) as we moved

from meeting annually with AIBS to running

independent BOTANY meetings and Scott Russell

was our first web-master and President 2002-3

during the period of hiring an executive director and

establishing the business office in St. Louis. But

that is not the story for now. In 2001 Gordon Uno

(who chairs the Society’s Education Committee)

became chair of the Department at Oklahoma and

began a concerted effort to strengthen and grow the

botanical component of this dual department. In

our second feature Gordon shares some of the

strategies he employs, and concerns he sees, for

building botany in colleges and universities today.

-Editor

Landmarks and Milestones in

American Plant Biology:

The Cornell Connection

ABSTRACT: Cornell University faculty, staff,

students, graduate students and post-docs made

landmark contributions to American plant biology.

Twenty-four were recognized by their election to the

U.S. National Academy of Sciences (Sections of

Botanical Science, Chemistry or Genetics). Four

who studied plants were recognized with a Nobel

Prize (J.B. Sumner, G.W. Beadle, R. Holley, B.

McClintock); eighteen served as President of the

Botanical Society of America (BSA); twenty were

BSA Merit Award winners and five received BSA

Centennial Awards. The landmarks and milestones

of Cornell “botanists” are presented.

Introduction

The Botanical Society of America’s Centennial in

2006 inspired us to examine the contributions

made to American plant biology by Cornellians in

the years since William Trelease (Cornell BS 1880)

chaired the organizing committee and became

President of the antecedent Botanical Society of

America (BSA) (1895-1905). Colleagues, who

attended our presentation at the BSA Centennial in

Chico, California (Kass 2006), encouraged us to

9 1

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

Editorial Committee for Volume 53

Joanne M. Sharpe (2009)

Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens

P.O. Box 234

Boothbay, ME 04537

joannesharpe@email.com

Nina L. Baghai-Riding (2010)

Division of Biological and Physical Sciences

Delta State University

Cleveland, MS 38677

nbaghai@deltastate.edu

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

Andrea D. Wolfe

(2007)

Department of EEOB

1735 Neil Ave., OSU

Columbus, OH 43210-1293

wolfe.205@osu.edu

Samuel Hammer (2008)

College of General Studies

Boston University

Boston, MA 02215

cladonia@bu.edu

Jenny Archibald (2011)

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

publish an account of our findings to catalyze faculty

and students at other colleges and universities to

examine the contributions of botanists at their

institutions. We are pleased to have the opportunity

to do so in the Plant Science Bulletin, co-founded

by Harriet Creighton—Cornellian and past BSA

president (1956) (Kass 2005).

When the current BSA was reorganized in 1906,

from three pre-existing organizations (Smocovitis

2006), Cornell Professor of Botany George F.

Atkinson (Cornell PhB 1885) was elected its first

President (1907, Table 1). From the time Cornell

University opened its doors in 1868, faculty and

students in the Department of Botany have made

pioneering contributions to American plant biology.

This is reflected in Ewan’s (1969) Short History of

Botany in the United States, published on the

occasion of the Eleventh International Botanical

Congress, held in Seattle, Washington. (It was the

second time the congress occurred in the United

States in over 40 years.) Interestingly, Cornell

University had hosted the Fourth International

Congress of Plant Sciences in Ithaca, New York in

1926, the first year it was held in the Americas (Kass

1999). L.H. Bailey (appointed first Professor of

Horticulture at Cornell in 1888) was concurrently

President of the Congress, the AAAS, and the BSA

in that year (Table 1).

An examination of the biographical entries in

American Men of Science (AMS), from its first

publication in 1906 through the seventh edition in

1944, also provided context for this study. James

McKeen Cattell published and edited this directory

of scientists and prefixed a “star” (*, asterisks) by

the “subject of research for about 1000 of the

entries.” In 1906 he noted, “The star means that the

subject of the biographical sketch is probably among

the leading thousand students of science of the

United States; but its absence does not necessarily

mean that the subject of the sketch does not belong

in that group.” Cattell continued to assign new stars

to approximately 250 men and women of science in

each of the five later volumes, and his son Jacques

(Cattell 1944a, b) continued the practice through the

seventh edition, 1944, the year of his father’s death.

In editions five through seven (1933-1944), an index

number after the star indicated the edition of the

book in which the first star was assigned. Cattell

identified the most “eminent American Scientists of

the day” and these scientists used his stars to order

themselves, thus his system played a “major role in

the American Scientific community” (Sokal 1995).

Another perspective on the highly coveted “star” is

offered by Rossiter (1982, p. 289), “There were two

awards whose value was apparent to all in the

1920s and 1930s: a ‘star’ in the AMS, and the

supreme accolade, the Nobel Prize.” Although

women had won suffrage by the 1920s, they were

clearly concerned about their opportunities for

advancement and employment, yet few stars were

affixed to women in botany during these years. Only

six women were starred in botany between 1906

and 1944 (Rossiter 1982, p 293); two were

Cornellians and one of these won an unshared

Noble Prize in 1983.

Although Cornell botanists made many contributions

before 1906, in the interest of brevity, and in

celebration of the BSA Centennial, we begin our

story with Atkinson and concentrate on Cornell’s

Departments of Botany and herbaria; reserving the

extensive contributions of Cornell’s earlier botanists

for another time.

Contributions from Cornell’s First Notable

Department of Botany (1868-1921)

Prentiss and Atkinson’s Department of Botany

George F. Atkinson (1854-1918), first president of

the reorganized BSA, studied with Albert N. Prentiss,

Cornell’s first Professor and Chair of Botany (1868-

1896). Prentiss had also influenced students who

studied the local flora (David Starr Jordan, Cornell’s

9 2

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

first MS 1872; William R. Dudley, Cornell BS 1874,

MS 1876), and inspired many who became notable

botanists (Joseph C. Arthur, Cornell DSc 1886;

Frederick V. Coville, Cornell AB 1887; W.R. Dudley;

Charles F. Millspaugh, in residence 1871-73; Willard

W. Rowlee, Cornell BL 1887, DSc 1893; and W.

Trelease) (Tables 1, 2, 3).

Atkinson replaced William R. Dudley (1849-1911),

who had been an undergraduate instructor at

Cornell (1874) and the first Assistant Professor in

its Department of Botany (1876-1883). David Starr

Jordan, the department’s first instructor in botany,

became the founding president of the newly

established Leland Stanford Jr. University, where

he appointed Dudley as one of their first professors

of Botany in 1892. (Most of Dudley’s herbarium

followed him to Stanford and is currently at CAS).

Upon the death of Prentiss in 1886, Atkinson became

head of Cornell’s Department of Botany, until his

death in 1918. That same year, Atkinson was

elected to the US National Academy of Sciences

(NAS) (Table 2). Within a few years, his former

department (by then in the College of Arts and

Sciences) would close and the New York State

College of Agriculture’s (NYSCA) Department of

Botany (established in 1913) would continue

Cornell’s pioneering contributions (see below).

Distinguished for his research with fungi, Atkinson

was also a respected teacher of General Botany

and Zoology. He encouraged young botanists, both

male and female. Three of his more notable students

were Elias J. Durand (Cornell AB. 1893, ScD. 1895),

Benjamin M. Duggar (1872-1956; Cornell PhD 1898)

and Margaret Clay Ferguson (1863-1951; Cornell

AB 1899, PhD 1901), all of whom were starred in

AMS (Table 3).

Duggar, instructor (1896-1900) and assistant

professor (1900-1901) in Cornell’s Department of

Botany, would soon head the first Department of

Plant Physiology (1907-1912) in the NYSCA at

Cornell. He was appointed by L.H. Bailey, who had

succeeded Isaac P. Roberts as Dean of the College

of Agriculture (1903) and had secured funds from

New York State to establish the New York State

College of Agriculture at Cornell University in 1904.

Plant Physiology merged with the new Department

of Botany (established 1913), when Duggar left

Cornell for Washington University, in St. Louis,

Missouri. Duggar was awarded a star in Plant

Physiology in the first edition of AMS (1906, Table 3)

and published the first text on the subject of Fungous

Diseases of Plants in 1909. He was President of the

BSA (1923), General Secretary and Chairman of the

Executive Committee for the Fourth International

Congress of Plant Sciences (1926), and edited its

Proceedings (Duggar 1929). In 1948, at age 71,

Duggar reported the first broad-spectrum antibiotic,

Aureomycin, produced by Streptomyces

aureofaciens. At the 1956 Golden Jubilee

celebration of the BSA, Duggar, along with four other

Cornellians, received one of the society’s first Merit

Awards (Table 4). He was acknowledged for

outstanding research in plant physiology, plant

pathology, and mycology, and for providing

inspiration, and high standards of scholarship to

many students.

One of those students, Margaret C. Ferguson, while

pursuing a doctorate in botany with Atkinson, had

also conducted a study of the common edible

mushroom under the direction of Duggar, during

1900-1901. In 1902, she published the first

successful method for germinating spores of

Agaricus campestris. Previously, French scientists

held the secret for successful germination of this

fungus. Starred in Botany in the second edition of

AMS (1910), Ferguson was also the first woman

elected Vice President of the BSA (1922) and the

first woman elected its President in 1929. She was

head of the Botany Department of Wellesley College,

Wellesley, Mass., and encouraged many students

to become botanists. Harriet B. Creighton, for

example, was awarded a graduate assistantship in

Cornell’s Department of Botany, in 1929, on

Ferguson’s recommendation (Kass 2005).

Contributions from Cornell’s NYS College of

Agriculture: Department of Botany (1913-1964) &

L.H. Bailey Hortorium (1935-1999)

More Notable Botany Departments

Liberty Hyde Bailey(1858-1954), as Dean (1903-

1913) of the NYSC at Cornell, established many

new departments related to botanical sciences

and served as the Director of the Cornell Agricultural

Experiment Station until 1913. Dean Bailey

appointed former students and colleagues, from

Cornell and elsewhere, to professorships in his

newly established departments (Coleman 1963;

also see below). Bailey reported the first detailed

study of plant growth under artificial light (1893). He

published over 1,000 articles and technical and

popular books, the more influential being his

Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (1914-1917),

Manual of cultivated plants (1924, 1

st

ed.; revised

1949), and Hortus Second (1941) with his daughter

Ethel Zoe Bailey (1889-1983). Hortus Third (1976)

was revised and expanded by the staff of the L.H.

Bailey Hortorium. In addition to serving as an officer

of the BSA (Table 1), Bailey was also honored with

a star in botany in the first edition of AMS (1906), and

elected to the NAS in 1917. In 1935, at Cornell

University, Bailey and his daughter Ethel Zoe

9 3

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

established the L.H. Bailey Hortorium (BH), one of

the first U.S. herbaria of cultivated plants, and, by the

1950s, one of the foremost palm herbaria of the

world. Bailey was the Hortorium’s first director and

daughter Ethel Zoe was appointed the first curator.

One of Bailey’s final duties as dean of the NYSCA

was to recall Professor Karl McKay Wiegand (1873-

1943) from Wellesley College in 1913, to head the

newly established Department of Botany in the

NYSCA, and to invite Rollins Adams Emerson to

head the Department of Plant Breeding (1914),

which Bailey had established in 1907 (with H.J.

Webber as its first head). Wiegand had earned his

PhD at Cornell in 1898 and was appointed assistant

then instructor there from 1894 through 1907. While

there, he met and married Ella Maude Cipperly

(Cornell AB 1904). Wiegand was then appointed

Professor of Botany at Wellesley College (1907-

1913) and was soon recognized with a star in

Botany in the second edition of AMS (1910). He was

elected President of the BSA in 1939.

Wiegand’s Department of Botany

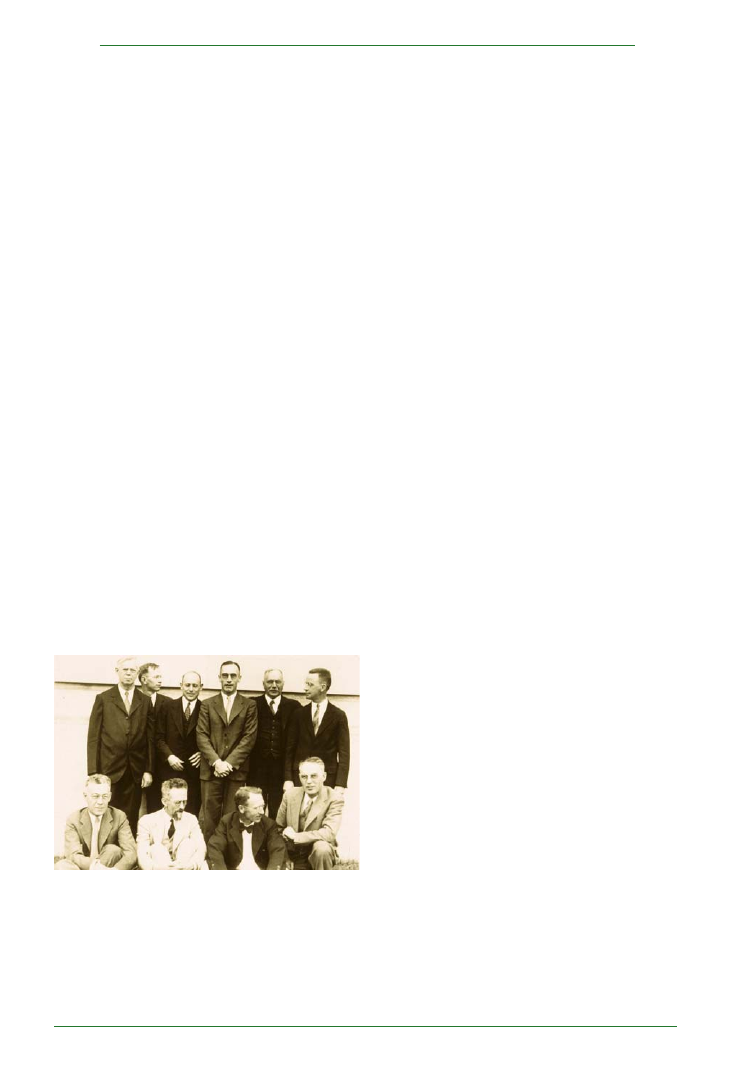

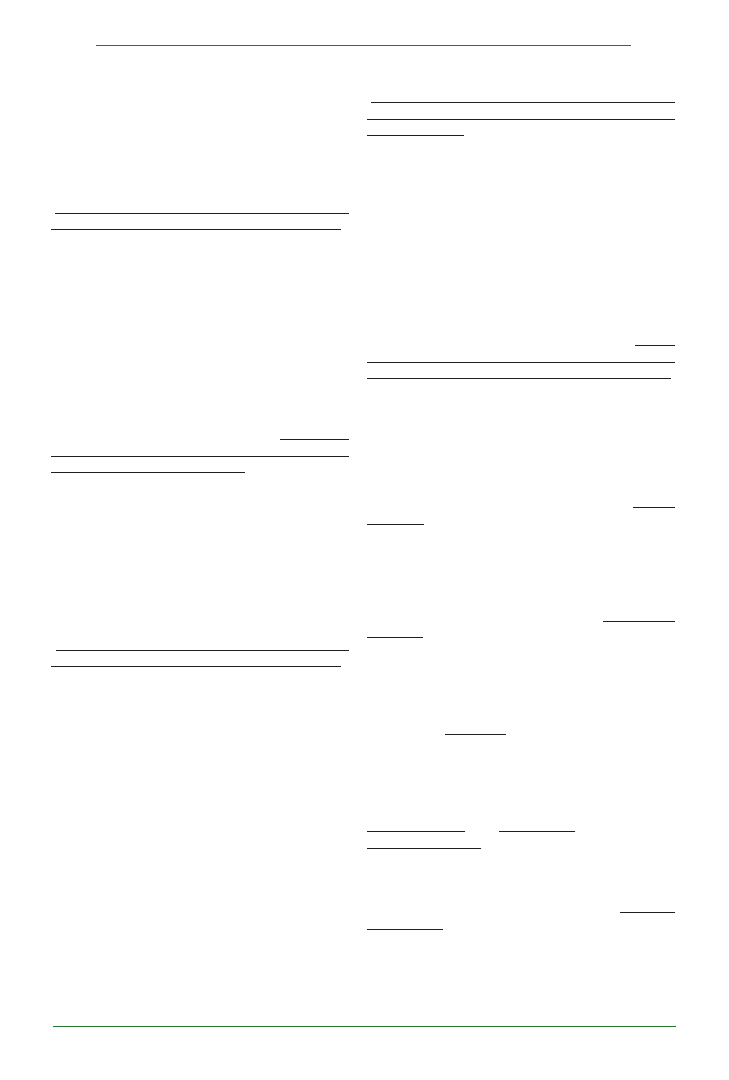

Wiegand hired many notable botanists (Figure 1)

who brought honors to his department by their

inspirational teaching, pioneering research, and

technical and educational publications. The staff in

Wiegand’s newly established Department of Botany

included Assistant Professor Lewis Knudson (who

was transferred from the former Department of

Plant Physiology, when Duggar left Cornell) and five

instructors, among whom were: Arthur J. Eames,

graduate of Harvard University (who was transferred

from Atkinson’s Department of Botany); Wiegand’s

spouse, Maude C. Wiegand, former Instructor in

Botany at Wellesley College; Otis Freeman Curtis

(Cornell PhD 1916), later assistant professor (1917)

then professor (1922) of Plant Physiology, and

William J. Robbins (Cornell PhD 1915) who later

became Head of the Department of Botany at the

University of Missouri, where he pioneered

experiments on tissue culture. Soon after, Robbins

became Dean of their Graduate School, later on

Director of the New York Botanical Garden, and

ultimately President of Fairchild Tropical Garden. In

addition, Wiegand had six assistants; the most

notable is Laurence H. MacDaniels (Cornell PhD

1917), who with Eames wrote an influential text in

plant anatomy (Table 5). MacDaniels later served

as head of Cornell’s Department of Floriculture and

Ornamental Horticulture (1940-1956).

Wiegand’s first research project at Cornell was to

continue his graduate student project, a study of the

local flora, in collaboration with A.J. Eames (1881-

1969), and in cooperation with graduate students,

staff, and other faculty members. This resulted in

The Flora of the Cayuga Lake Basin, New York

(1925, Table 5), which was an expansion of Dudley’s

(1886) Cayuga Flora published 40 years previously.

The plant specimens that Wiegand’s group

collected were an important resource for

documenting the local flora, and the NYSCA

Department of Botany Herbarium was an outcome

of this project. When Atkinson’s former department

was closed, around 1921, Wiegand arranged for

the transfer of the previous Department of Botany

herbarium [based originally on the important

collections of Horace Mann Jr. (1844-1868)] to the

NYSCA Department of Botany. Wiegand then

merged his department’s herbarium with the earlier

herbarium to form CU (named Wiegand Herbarium,

in 1951, after Wiegand’s death in 1942). In 1977, the

herbaria of CU and BH were merged. Thus Cornell’s

world-renowned herbaria—The original Cornell

University Herbarium, The Wiegand Herbarium,

and The Bailey Hortorium Herbarium—were finally

one.

One of Wiegand’s more notable students, Bassett

Maguire (Cornell PhD 1938), later a staff member

of the New York Botanical Garden, directed the first

of 42 expeditions to the sandstone Guayana

Highland of northern South America (Howard and

Moon 1990).

Eames was soon recognized with a star in Botany

in the fourth edition of AMS (1927). He served the

BSA as secretary (1927-1931), Vice President

(1932), and President (1938), and was honored

with one of the first BSA Merit Awards (1959) for his

“sustained researches on the morphology and

Figure 1. Cornell’s Department of Botany Faculty (1931)

Top row, left to right: Karl M. Wiegand, Walter C. Muenscher,

E.M. Weller (visitor), Edwin F. Hopkins, R.B. Thompson

(visitor), Lester W. Sharp.

Bottom row, left to right: Arthur J. Eames, Loren C. Petry,

Donald Reddick, Otis F. Curtis. (Courtesy of L.H. Bailey

Hortorium Archives)

9 4

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

anatomy of vascular plants and for his noteworthy

contributions to our knowledge of floral development

and evolution.” One of Eames’ notable students is

Natalie Browning Whitford (Cornell MS 1943, PhD

1947) (see Natalie W. Uhl below).

The staff of Wiegand’s Department of Botany was

enlarged with appointments of notable botanists,

Jacob R. Schramm, Loren C. Petry, Walter C.

Muenscher, and Lester W. Sharp. Schramm (1885-

1976) joined Wiegand’s department in 1915 as

Assistant Professor of Botany (Professor 1917-

1925). He was editor-in-chief of Botanical Abstracts

from 1921-1925 and founder and first editor-in-

chief of Biological Abstracts [now Biosis] (1924-

1937), first issued in December 1926. Schramm

had been secretary of the BSA (1918-1922), elected

Vice President (1923) and later its President in

1925. He was starred in Botany in the third edition

of AMS (1921) and was honored with the Botanical

Society of American’s Merit Award (1969) for his

studies of the “ecology of the black mining wastes

of the Pennsylvania anthracite region,” and for his

work as editor of Biological Abstracts.

Petry (1887-1979), a paleobotanist and

distinguished teacher, was hired at Cornell in 1925.

Vice-President of the BSA in 1937, and starred in

Botany in the sixth edition of AMS (1938), he was

also honored with a BSA Merit Award as an “unusually

effective botanical teacher, who has skillfully guided

the careers of thousands of students in the right

direction, and a wise and generous counselor in

scientific affairs” (Tables 1, 3, 4). Petry’s most

notable student was Harlan P. Banks (Cornell PhD

1940) (see below).

Muenscher (1891-1963, Cornell PhD 1921), known

as the “Wizard of Weeds,” and an eminent American

scientist (Table 3), received a BSA Merit Award in

1960 for “many distinguished contributions,

especially his books on weeds, aquatic plants,

poisonous plants and garden herbs (Table 5). His

lifelong devotion to all phases of botany has

stimulated the lives and careers of his numerous

students.” Many readers of this article may recall

keying out their first early spring wild flowers or

woody plants using Muenscher’s books.

Sharp (1887-1961), a graduate of the University of

Chicago, joined Wiegand’s department as an

instructor in 1914 (Professor in 1920). Sharp was

the major professor of Barbara McClintock (Cornell

BS 1923, MA 1925, PhD 1927; Nobel Laureate

1983), and Harriet Creighton (Cornell PhD 1933),

and was on the PhD committees of R.A. Emerson’s

students, George W. Beadle (Cornell PhD 1930;

Nobel Laureate 1958) and Marcus M. Rhoades

(Cornell PhD 1932).

Two years after McClintock arrived at Cornell, Sharp

published the first edition of his world-renowned

textbook, Introduction to Cytology (1921).

McClintock, who would become Sharp’s most

notable graduate student and the Department of

Botany’s most famous alumna, used this text while

enrolled in Sharp’s cytology class the same year it

was issued. The third edition of Sharp’s cytology

book (1934) included unpublished research of his

distinguished students, McClintock and Creighton.

Sharp’s keen wit and non-conformist outlook

produced such works as Eoörnis pterovelox

gobiensis (1928), a spoof on scientific inquiry and

pompous investigators, and A Nuclear Century

(1931) his poetic address upon retiring as BSA

President (Table 1, see Kass 2005). Sharp served

as Secretary of the 1926, Fourth International

Congress of Plant Sciences Program Committee

(Schramm was Chair) and was a member of the

Executive Committee. Within a few years he was

elected Vice President (1929) and President (1930)

of the BSA, and was a member of the editorial board

of the American Journal of Botany (1932-1937). He

was awarded a star in Botany, in the fourth edition

of AMS (1927), and was honored with a BSA Merit

Award (1958) for his contributions, which “made

plant cytology a significant field of botany.”

Cooperation with Emerson’s Department of Plant

Breeding:Golden Age of Plant Cytogenetics at

Cornell

Many students majoring in other departments at

Cornell studied with faculty in the Department of

Botany; most notable were students who came to

work with R.A. Emerson (1873-1947), head of

Cornell’s Plant Breeding Department (1914-1942).

Emerson had established a school of plant genetics

at Cornell, a milestone comparable to T.H. Morgan’s

school of Drosophila genetics at Columbia

University (Kass, Bonneuil & Coe 2005). Barbara

McClintock (1902-1992), as an instructor in the

Department of Botany (1927-1931), provided

guidance and leadership to Emerson’s students,

G.W. Beadle, M.M. Rhoades, and post-doctoral

National Research Council Fellow Charles R.

Burnham (1929, 1930) (Figure 2), and in her own

department to H.B. Creighton (see also Kass 2007).

Rhoades, a 1962 BSA Merit Awardee, and a student

in Plant Breeding and Botany at Cornell during the

Golden Age of maize genetics, has reviewed the

cooperative efforts that this group of students had

made towards furthering the field of plant

cytogenetics (Rhoades 1984, Kass & Bonneuil

2004).

We will mention only a few of McClintock’s landmark

publications, which Rhoades (1984) emphasized

(see Kass & Bonneuil 2004). While McClintock was

still a graduate student, she and L.F. Randolph

(Cornell PhD 1921) published the first report of a

9 5

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

.

triploid corn plant and described the behavior of its

chromosomes (Randolph & McClintock 1926, see

Kass 2003). By June of 1929, Instructor McClintock

had published the first ideogram of corn

chromosome morphology illustrating the 10 haploid

chromosomes in the first mitotic division of the

microspore (McClintock 1929; see Kass 2003). By

1930, McClintock had published the first cytological

description of pachytene chromosomes in corn; the

movement of the chromosomes (in a translocation

heterozygote) provided an explanation for semi-

sterility in a strain of corn plants that Burnham had

brought with him from Wisconsin. With botany

student Henry E. Hill, McClintock published the first

paper linking a gene to a chromosome in corn,

using cytological methods and trisomic ratios

(McClintock & Hill 1931, see Kass & Bonneuil

2004).

But McClintock’s most noted early contribution is

the paper she published with graduate student

Harriet Creighton in 1931, on the first demonstration

of crossing over at the cytological level (McClintock

1931, Creighton and McClintock 1931, see Kass

2005). Creighton’s crossing-over paper was the

basis for her PhD dissertation (1933), which was

suggested by McClintock. Their landmark study

provided additional proof for T.H. Morgan’s

chromosome theory of heredity, for which he won a

Nobel Prize in 1933 (Coe & Kass 2005).

Creighton (1909-2004) left Cornell in 1934 and later

became head of the Botany Department at Wellesley

College. She retired as Ruby F.H. Farwell Professor

Emerita. Creighton was the third woman President

of the BSA in 1956 (Vice-President, 1955), and the

first woman elected secretary of the BSA (1950-

1954). She was editor of the Plant Science Bulletin

(1958) and made many behind-the-scenes

contributions to botanical education. Even after

retirement, she was recognized for her contributions

to botanical science with the Large Gold Medal of

the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1985)

(Kass 2005).

More notable plant scientists

Even before McClintock was recognized for her

Nobel Prize winning research, she was starred in

Botany in AMS (1944) and, soon after her major

papers on mobile genetic elements and gene

expression were published, the BSA honored her

with their 1957 Merit Award (Kass 2007). In addition

to McClintock and those students mentioned

previously, the Department of Botany boasts many

other influential and prominent students of the

botanical sciences. For example, in 1934, Adriance

S. Foster (Cornell BS 1923, see Hirsch & Kirchanski

2006) became the first plant anatomist in the newly

reorganized Department of Botany, University of

California, Berkley; Sterling Emerson (Cornell BS

1922), son of R.A. Emerson, became Professor at

the California Institute of Technology and a member

of the NAS; Chester A. Arnold (Cornell PhD 1928)

was Curator of Fossil Plants at University of

Michigan; Paul R. Burkholder (Cornell PhD 1929)

pursued quantitative studies on auxins and was

elected to the NAS in 1949; Stanley J. Smith (Cornell

MS 1939) was Curator of Botany, New York State

Museum, Albany, NY; Arthur W. Galston (Cornell BS

1940), Professor of Plant Physiology, Yale University,

is the author of notable plant biology textbooks, and

has made pioneering studies on plant hormones

and plant growth and development; and Natalie W.

Uhl, (Cornell PhD 1947), Professor Emerita, L.H.

Bailey Hortorium, Department of Plant Biology, and

a BSA Centennial winner, co-authored with John

Dransfield (1987) the celebrated Genera Palmarum:

A Classification of Palms Based on the Work of

Harold E. Moore, Jr., recently revised (in press).

Furthermore, in addition to Creighton, Cornellians

served as Secretary of the BSA (Table 1).

Expansion of Cornell’s Department of Botany

Soon, other professors joined Cornell’s Department

of Botany and made notable contributions to their

fields. Among these was Daniel Grover Clark

(Cornell PhD 1936) who with O.F. Curtis authored

a well-known textbook on plant physiology (Table

5). Harlan P. Banks succeeded Petry in 1949 and

became head of the department after Knudson

stepped down in 1952. Banks authored many

influential publications in the field of paleobotany,

concentrating on the evolutionary history of early

land plants (Banks 1970). He served as BSA

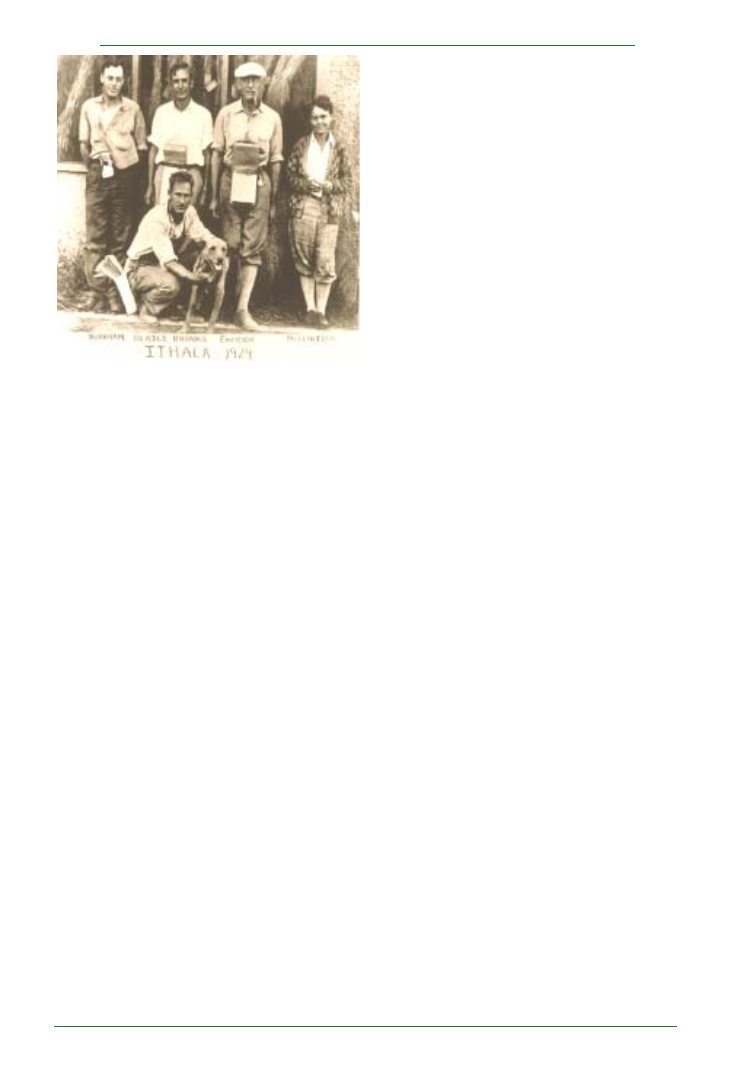

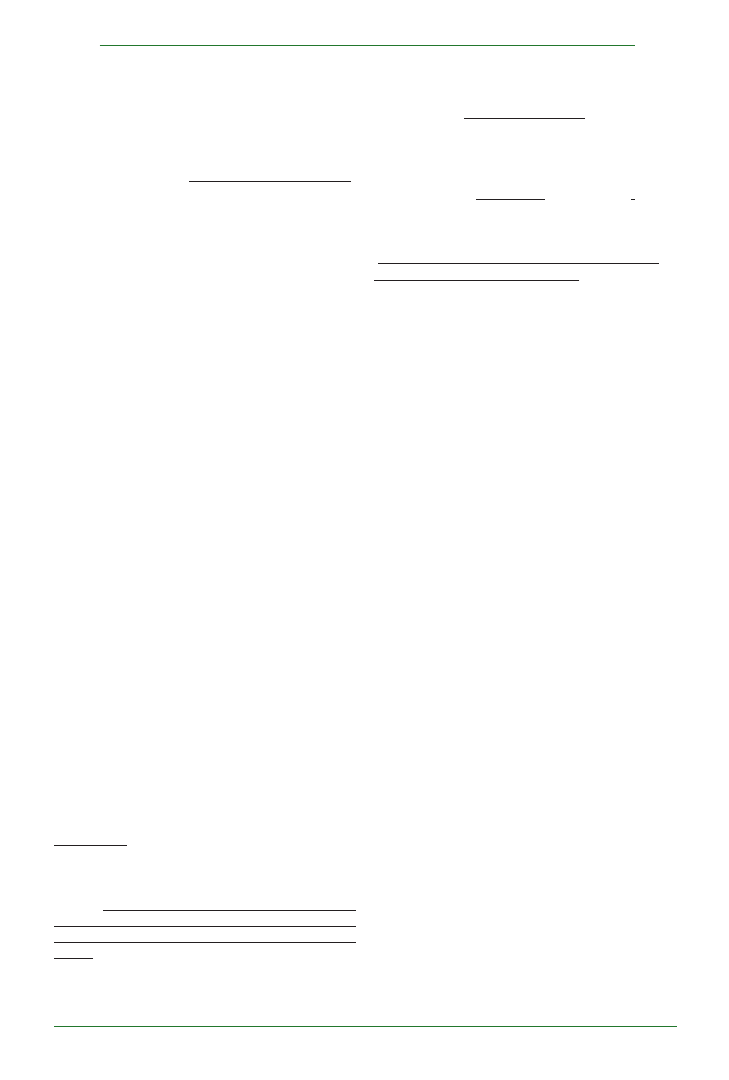

Figure 2. Maize Researchers, Cornell University Emerson

Garden, 1929

Left to right: Charles R. Burnham (National Research

Council Fellow), George W. Beadle (kneeling, PhD 1930),

Marcus M. Rhoades (PhD1932), Professor Rollins A.

Emerson (Head, Department of Plant Breeding), Instructor

Barbara McClintock (PhD 1927). (Courtesy of W.B. Provine)

9 6

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

President and Treasurer (Table 1), received a BSA

Merit Award (1975) for distinguished teaching of

undergraduate and graduate students and for

numerous contributions to our knowledge of early

land vegetation, and was elected to the NAS (Table

2). Frederick C. Steward, first to show that a single

cell from a vegetative plant can be cultured to

produce a whole plant, joined the department in

1950, was elected to the Royal Society (the national

academy of sciences of the UK) in 1957, and

honored with a BSA Merit Award (1961). (McClintock

was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society,

in 1989.) Tables 1-4 include additional Cornell

plant scientists or geneticists who have made

notable contributions to their fields. A few share

joint appointments in the current Department of

Plant Biology (see below).

A New Vision for Botany at Cornell: A Department

of Plant Biology

With the creation of a Division of Biological Sciences

within NYSCA at Cornell in 1964, members of the

Department of Botany, which Bailey had established

in 1913, joined with a few faculty members from the

Departments of Zoology and Plant Breeding to form

a new unit called the Section of Genetics,

Development and Physiology (GDP, established

1965; and CU herbarium became a separate unit

within NYSCA; Table 6); Cornell’s formerly

distinguished Department of Botany had

disappeared! In 1965, Barbara McClintock returned

to this new Section as one of the first Andrew

Dickson White Visiting Professors-at-Large. She

visited the campus once or twice a year for the next

10 years, hosted by geneticists Adrian M. Srb, Bruce

Wallace (Table 2) and Section Chair Harry Stinson.

New faculty interested in plant growth and

development soon joined the Section (we mention

only a few)—Andre T. Jagendorf (Cornell BS 1948;

hired 1966), L.H. Bailey Professor Emeritus, was

responsible for discoveries on biochemical

reactions in photosynthesis; he provided

experimental evidence for hydrogen ion gradients

across membranes as an energy intermediate, a

hypothesis proposed by Mitchell (and for which

Mitchell was awarded a Nobel Prize). Roderick K.

Clayton, who unraveled mysteries of how light

energy is trapped, joined the Section in the same

year (retired 1983). Jagendorf and Clayton were

elected to the NAS (Table 2). Recently (July 2007),

Jagendorf received one of the first Fellow of the

American Society of Plant Biology (ASPB) Awards,

granted in recognition of distinguished and long

term contributions to plant biology and service to

the Society. In 1977, the name of the Section of GDP

was changed to Botany, Genetics and Development

(BGD), which more accurately reflected the interests

of its members (and CU herbarium merged with BH

herbarium; see Table 6). Earlier (1971), NYSCA

had been renamed The New York State College of

Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell (CALS). By

1980, the Section was separated into a Section of

Plant Biology and a Section of Genetics and

Development. New faculty members were recruited

for positions in the Section of Plant Biology. Karl J.

Niklas, L.H. Bailey Professor, was hired to fill the

position vacated by Banks in 1978. Niklas, former

editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Botany

(1995-2004) and a BSA Merit Award winner (1996),

authored several books including The Evolutionary

Biology of Plants (1997) and recently received a BSA

Centennial Award. He is currently BSA President

elect (Table 1). June B. Nasrallah, who had received

her PhD (1977) in the former Section of Genetics,

Development and Physiology, with Professor Adrian

M. Srb (a former student of G.W. Beadle), was hired

in 1985. J. Nasrallah was recently elected to the

NAS for her exemplary studies on self-incompatibility

in Brassica, joining other Cornell plant biologists

who have received such distinction (Table 2). She

occupies the first Barbara McClintock Professorship

in the Department of Plant Biology (CALS).

The Legacy of Liberty Hyde Bailey

When the Division of Biological Sciences was

dissolved in 1999, the Section of Plant Biology and

the L.H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium were joined.

The circle was completed and Cornell’s

Departments of Botany and herbaria were once

again united in a single Department of Plant Biology

(Table 6), currently chaired by William L. Crepet, a

recent BSA Merit Awardee.

Cornell’s Notable Botanists

Nobel Laureates

At the 1957 BSA Banquet, retiring President Harriet

Creighton suggested that we make clear that botany

includes the study of all plants and that we “call

ourselves botanists with some pride in our voices.”

We are proud to recognize four Nobel Laureate

Cornellians who have made major contributions to

science using plants as their research organisms.

(We remind our readers that fungi were still

considered plants until 1968.) Barbara McClintock

received an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or

Medicine (1983) for her “discovery of mobile genetic

elements” (Indian corn); George W. Beadle, shared

a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1958) for

the “discovery that genes act by regulating definite

chemical events” (Bread mold); Robert W. Holley

(Cornell PhD 1947) shared a Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine (1968) for the “interpretation

of the genetic code and its function in protein

synthesis” (yeast); and James B. Sumner shared a

Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1946) “for his discovery

9 7

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

that enzymes can be crystallized” (Jack Bean meal).

It is interesting to note that Sumner’s first publication

of the crystallization of urease extracted from Jack

Bean meal [Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC], in 1926,

provided a further demonstration that the urease

enzyme is a protein. His work was based on the

research of his graduate student Viola Arvin Graham,

who provided the initial Experimental proof of the

protein nature of urease for her PhD (1925), awarded

the previous year. In his Nobel Prize acceptance

speech, Sumner acknowledged the collaborative

efforts of “V.A. Graham,” giving no indication that

Graham was a woman.

Cornellian-National Academy of Sciences

members, BSA Merit/Centennial Awardees and

American Men of Science Honorees

Between 1902 and 2003 a considerable number of

Cornellians, who conducted research with plants,

were elected to the United States NAS (Table 2). In

the early years, members were elected to specific

sections of the NAS (i.e. Botany) on

recommendations from Academy members in that

section. Many academy members were also former

officers of the BSA (Table 1) and were starred in AMS

(Table 3).

The Botanical Society of America celebrated its 50th

Golden Jubilee Anniversary in 1956, by awarding

Certificates of Merit to 50 botanists in all botanical

fields. As BSA President in 1956, Harriet Creighton

presented these honors to four former Cornellians:

B.M. Duggar, A.J. Eames, W.J. Robbins, and G.W.

Beadle. In that year, a study based on the seventh

edition of AMS (1944) revealed that Cornell University

ranked in the top three American Universities in

graduating PhDs in Botany (Greulach 1956). Sixteen

percent of the botanists newly starred in the seventh

edition of AMS, had graduated from Cornell University

(Table 3, see Cattell 1944).

In the second 50 years of the BSA, 16 additional

Cornellians were presented with BSA Merit Awards

(Table 4). And in 2007, a Cornell University plant

biologist has been privileged to accept this tribute

(Table 4). The 100

th

anniversary of the BSA was

celebrated at BOTANY 2006, in Chico, California,

with 100 plant biologists receiving Centennial

Awards. Five Cornellians were so honored: W.

Hardy Eshbaugh (Cornell BA 1959), Jack B. Fisher

(Cornell BS 1965, MS 1966), Karl J. Niklas, Dominick

J. Paolillo, Jr. (Cornell BS 1958), and Natalie W. Uhl

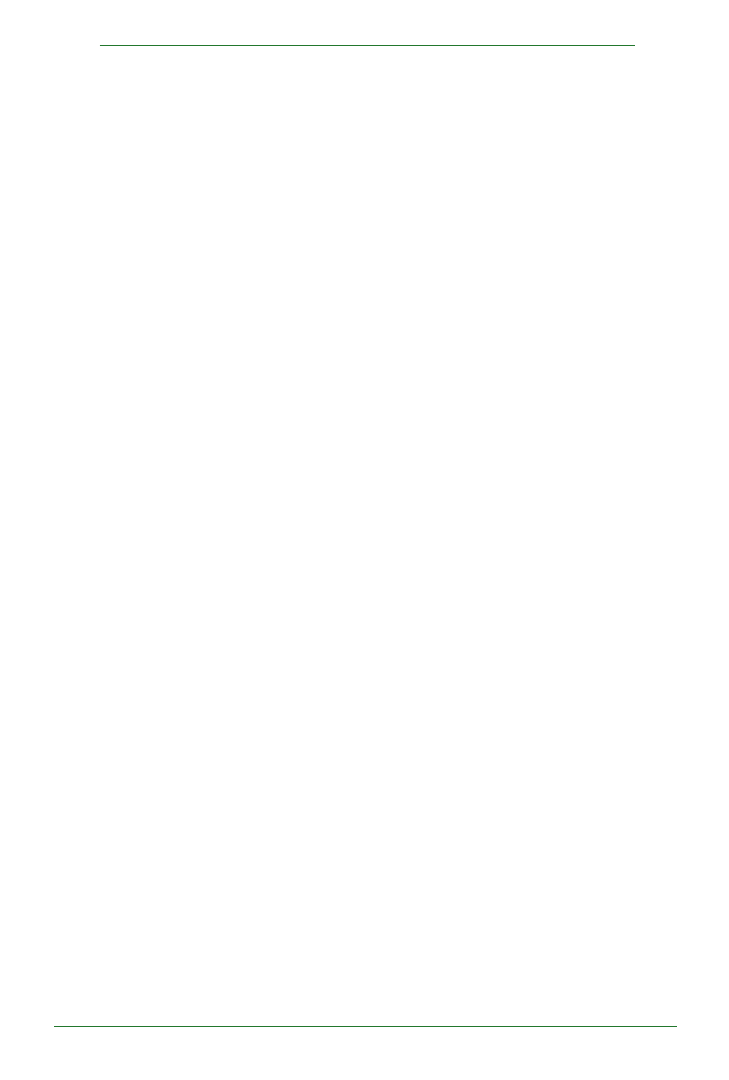

(Cornell PhD 1947), (Figure 3). We are also proud

that V. Betty Smocovitis (Cornell PhD 1988), the

BOTANY 2006 keynote speaker and botanical

historian, received her botanical training in Cornell’s

Section of Plant Biology.

We can conclude that modern plant taxonomy has

caused a diaspora for the former plant kingdom,

having some of its past members now dispersed

throughout other kingdoms of the natural world. Yet,

as Creighton suggested, we can still be proud of all

researchers who work with plants, fungi, and bacteria

(and study their history), even though they may not

currently consider themselves Botanists.

Acknowledgments. We gratefully acknowledge The

Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell

University Library, and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium

Library and Archives, Cornell University, for

assistance with documentation; The Department

of Plant Biology and The Department of Plant

Breeding & Genetics, Cornell University, for logistical

support; Members of the former Sections of

Genetics, Development & Physiology and Botany,

Genetics & Development, and Members of The L.H.

Bailey Hortorium for insights and documents,

especially Robert Dirig, for thoughtful discussion

and reviewing earlier drafts of the manuscript;

Professor Dominick Paolillo, who gifted LBK his

copy of Ewan’s history when she was his graduate

student at Cornell in the early 1970s; Professor

Richard Korf, Department of Plant Pathology, for

bringing Ferguson’s publication and other

documents to our attention; Professors R.P. Murphy,

K. Gale, R.H. Whalen, A.T. Jagendorf, R.P. Korf, D.M.

Bates, with special thanks to K.J. Niklas, for

suggested revisions to the manuscript. LBK

conducted part of these investigations under the

auspices of NSF grants SBR9511866 &

SBR9710488.

Literature Cited:

Figure 3. BSA Centennial Award winners with William L.

Crepet, Chair of their Department of Plant Biology, Cornell

University. Left to right: Dominick J. Paolillo, Jr., W.L.

Crepet, Karl J. Niklas, and Natalie W. Uhl. (photo by Ed Cobb,

9 June 2007)

9 8

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

Cattell JM (editor). 1906 1

st

ed., 1910 2

nd

ed., 1921 3

rd

ed.,

1927 4

th

ed., 1933 5

th

ed. American Men of Science: A

Biographical Directory. The Science Press, New York,

NY.

Cattell, JM and J Cattell (editors). 1938 6

th

ed. American

Men of Science: A Biographical Directory, The Science

Press, New York, NY.

Cattell, J (editor). 1944a 7

th

ed. American Men of Science:

A Biographical Directory, The Science Press, Lancaster,

PA:

Cattell, J 1944b. American Men of Science: Scientific men

receiving stars in the seventh edition. Science 100 (No.

2589, Aug.): 126-129.

Banks, HP 1970. Evolution and plants of the past.

Wadsworth Pub. Co., Belmont, Calif.

Coe, E and LB Kass. 2005. Proof of physical exchange of

genes on the chromosomes. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Science 102 (No. 19, May): 6641-6646.

Coleman, GP. 1963. Education and Agriculture, A History

of the New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell

University. Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Duggar, BM (editor). 1929. Proceedings of the International

Congress of Plant Sciences, Ithaca, New York, August

16-23, 1926. George Banta Publishing Company, Menasha,

Wis.

Dudley, WR 1886. The Cayuga Flora. Part I: A Catalogue

of the Phaenogamia Growing Without Cultivation in the

Cayuga Lake Basin: Ithaca, N.Y., Andrus & Church.

Ewan, J (editor). 1969. A Short History of Botany in the

United States. Hafner Pub. Co., New York. [International

Botanical Congress 11

th

: 1969, Seattle Washington]

Ferguson, MC 1902. A Preliminary Study of the Spores of

Agaricus campestris and other Basidiomycetous Fungi.

USDA, Bureau of Plant Industry, Bulletin No. 16, Washington,

Government Printing Office.

Graham, Viola A. 1925. Experimental Proof of the Protein

Nature of Urease. PhD Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca,

N.Y.

Greulach, VA. 1956. Origins of American Botanists. Plant

Science Bulletin 2(1, Jan.): 4-6.

Hirsch, AM and SJ Kirchanski. 2006. Adriance S. Foster,

an academic grandchild remembers. Plant Science Bulletin

52 (2, spring): 42-45.

Howard, RA and BM Moon. 1990. Bassett Maguire—An

annotated biography, in The Bassett Maguire Festschrift:

A Tribute to the Man and his Deeds, edited by William R.

Buck, Brian M. Boom, and Richard A. Howard. Memoirs

of the New York Botanical Garden. Volume 64, Bronx, NY.

Kass, LB. 1999. Barbara McClintock and the 1926

International Botanical Congress. XVI International

Botanical Congress, Abstracts. Pg. 474.

Kass, LB. 2003. Records and recollections: A new look

at Barbara McClintock, Nobel Prize-Winning geneticist.

Genetics 164 (August): 1251-1260.

Kass, LB. 2005. Harriet Creighton: Proud botanist. Plant

Science Bulletin. 51(4): 118-125.

Kass, LB. 2006. Landmarks and milestones in American

Plant Biology; The Cornell connection. Botany 2006,

Abstracts, Scientific Meeting, July 29-August 2, 2006:

Abstract #751, Pg. 340. http://

www.2006.botanyconference.org/engine/search/

index.php?func=detail&aid=522

Kass LB. 2007. Barbara McClintock (1902-1992), on

Women Pioneers in Plant Biology, American Society of

Plant Biologists website, Ann Hirsch editor. Published

online, March 2007:

h t t p : / / w w w . a s p b . o r g / c o m m i t t e e s / w o m e n /

pioneers.cfm#McClintock

Kass, LB and C Bonneuil. 2004. Mapping and seeing:

Barbara McClintock and the linking of genetics and cytology

in maize genetics, 1928-1935. Chap. 5, pp. 91-118, in

Classical Genetic Research and its Legacy: The Mapping

Cultures of 20th Century Genetics, edited by H.J.

Rheinberger and J.P. Gaudilliere. London: Routledge.

Kass, LB, C Bonneuil, and E Coe. 2005. Cornfests, cornfabs

and cooperation: The origins and beginnings of the Maize

Genetics Cooperation News Letter. Genetics 169 (April):

1787-1797.

Niklas, KJ. 1997. The Evolutionary Biology of Plants.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Rhoades, MM. 1984. The early years of maize genetics.

Annual Review of Genetics 18:1-29.

Rossiter, MW. 1982. Women Scientists in America,

Struggles and Strategies to 1940. The Johns Hopkins

University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Smocovitis, VB. 2006 One hundred years of American

botany: a short history of the Botanical Society of America.

American Journal of Botany 93: 942-952.

Sokal, M. 1995. Stargazing: James McKeen Cattell,

American Men of Science, and the reward structure of the

American scientific community, 1906-1944, pp. 64-86, in

Psychology, Science, and Human Affairs: Essays in honor

of William Bevan, edited by Frank Kessel. Westview

Press, Bolder, CO.

Sumner JB. 1926. The isolation and crystallization of the

enzyme urease. Journal of Biological Chemistry 69:

4355–4441.

Uhl, NW and J Dransfield. 1987. Genera Palmarum: a

classification of palms based on the work of Harold E.

Moore, Jr., with illustrations by Marion Ruff Sheehan; L.H.

Bailey Hortorium, Ithaca, N.Y., International Palm Society

(Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas).

Dransfield, J, NW Uhl, CW Asmussen, WJ Baker, MM

Harley, CN Lewis. Genera Palmarum: Evolution and

Classification of Palms, 2

nd

edition (In Press).

Bibliography:

Atkinson, GF. 1896. Albert Nelson Prentiss. Botanical

Gazette XXI (May): 283-289.

BH, Herbarium of the LH Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University

http://bhort.bh.cornell.edu/herb.htm

(accessed 6 June

2007).

otanical Society of America Membership Directory and

andbook, 2005. Botanical Society of America, St. Louis,

MO.

Dudley Memorial Volume, Containing a Paper by William

Russel Dudley and Appreciations and Contributions in

his Memory by Friends and Colleagues. 1913. Stanford,

California.

Fitzpatrick, HM. 1926. An Historical Sketch of the Early

Days of Botany at Cornell. Unpublished manuscript in the

Department of Plant Pathology reprint collection, Cornell

University, Ithaca New York.

Fifty Years of Research at the Cornell University

Agricultural Experiment Station, 1887-1937. Cornell

University Agricultural Experiment Station. Ithaca, New

York.

Horace Mann, Jr. (1844-1868). http://bhort.bh.cornell.edu/

mann.htm (accessed 6 June 2007).

Kass, LB. 2000. Barbara McClintock, *Botanist, cytologist,

9 9

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

geneticist. American Journal of Botany 87(6): 64.

Knudson, L. 1938. A Brief History of the Department of

Botany [New York State College of Agriculture].

Unpublished manuscript, in the Department of Plant Biology

files, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Leonard, JW. (editor). 1914. Woman’s Who’s Who of

America, A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary

Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915. The

American Commonwealth Company, N.Y.

National Academy of Sciences, Membership Directory:

h t t p : / / w w w . n a s o n l i n e . o r g / s i t e /

Dir?sid=1011&view=basic&pg=srch

;

Deceased Member Data:

h t t p : / / w w w . n a s o n l i n e . o r g / s i t e /

Dir?sid=1021&view=basic&pg=srch.

Nobel Prize.org. All Nobel Laureates (by year beginning in

1901):

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/lists/all/

One hundred Years of Agricultural Research at Cornell

University: A Celebration of the Centennial of the Hatch

Act, 1887-1987. Office for Research, College of Agriculture

and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

Plant Pathology Herbarium (CUP), Cornell University:

http://www.plantpath.cornell.edu/CUPpages/CUP.html.

Royal Society, London: List of Royal Society Fellows,

http://www.royalsoc.ac.uk/page.asp?id+1727

(accessed

12 June 2007).

Selkrig, JH (editor). 1894. History of Cornell, Natural Science,

Botany, Chapter XV, in Landmarks of Tompkins County,

New York, D. Mason & Co. Publishers.

Steer, WC (editor). 1958. Botanical Society of America,

Fifty Years of Botany; Golden Jubilee Volume of the

Botanical Society of America. McGraw-Hill, New York,

NY.

Stafleu, FA and RS Cowan. 1981. Taxonomic Literature,

2

nd

ed. Vol. 3, pp. 278-279.

Visher, SS. 1947. The starred biologists. American

Naturalist 81 (No. 800. Sept/Oct.): 321-329.

-Lee B. Kass, Visiting Professor, L.H. Bailey

Hortorium

Chair, BSA Historical Section

Department of Plant Biology

Cornell University, Ithaca NY

LBK7@cornell.edu

-Edward Cobb

Department of Plant Biology

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

EC38@cornell.edu

_______________________________________________________________________________

Table 1. Cornellians who served as Officers of the Botanical Society of America (1907-present)

President:

Vice-President:

George F. Atkinson

1907

Benjamin M. Duggar

1912

William Trelease

1918

Benjamin M. Duggar

1914

Joseph C. Arthur

1919

Margaret C. Ferguson

1922

Benjamin M. Duggar

1923

Jacob R. Schramm

1923

Jacob R. Schramm

1925

Lester W. Sharp

1929

Liberty H. Bailey

1926

Arthur J. Eames

1932

Margaret C. Ferguson

1929

Karl M. Wiegand

1935

Lester W. Sharp

1930

Loren C. Petry

1937

C. Stewart Gager

1936

William J. Robbins

1938

Arthur J. Eames

1938

Paul R. Burkholder

1945

Karl M. Wiegand

1939

Adriance S. Foster

1948

William J. Robbins

1943

Harriet B. Creighton

1955

Adriance S. Foster

1954

Arthur W. Galston

1967

Harriet B. Creighton

1956

Harlan P. Banks

1968

Arthur W. Galston

1968

Harlan P. Banks

1969

Secretary:

W. Hardy Eshbaugh

1988

Karl J, Niklas (President

2008

Jacob R. Schramm

1918-1921

Elect 2007)

Arthur J. Eames

1927-1931

Loren C. Petry

1933-1936

Treasurer:

Paul R. Burkholder 1940-1944

Harlan P. Banks

1965-1967

Harriet B. Creighton 1959-1954

______________________________________________________________________________

100

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

_______________________________________________________________________________

Table 2. Cornellian members of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (affiliated with plant

sciences at Cornell).

William Trelease

1902

Paul R. Burkholder

1949

Liberty H. Bailey

1917

Robert W. Holley

1967

George F. Atkinson

1918

Adrian M. Srb

1968

Benjamin M. Duggar

1927

George F. Sprague

1968

Rollins A. Emerson

1927

Sterling H. Emerson

1970

Lewis J. Stadler

1938

Bruce Wallace

1970

William J. Robbins

1940

Roderick K. Clayton

1977

George W. Beadle

1944

Harlan P. Banks

1980

Barbara McClintock

1944

Andre T. Jagendorf

1980

Milislav Demerec

1946

Gerald R. Fink

1981

Marcus M. Rhoades

1946

Steven D. Tanksley

1995

James B. Sumner

1948

June B. Nasrallah

2003

_______________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

Table 3. Cornellians recognized as eminent plant scientists in American Men of Science (1906-1944)

and first honored with a Star in Botany (or related fields of

1

Agriculture,

2

Plant Physiology,

3

Mycology or

4

Plant Pathology).

Joseph C. Arthur

1906

Margaret C. Ferguson

1910

George F. Atkinson

1906

Karl M. Wiegand

1910

Liberty H. Bailey

1

1906

Rollins A. Emerson

1921

Frederick V. Coville

1906

Jacob R. Schramm

1921

William R. Dudley

1906

Herbert H. Whetzel

4

1921

Benjamin M. Duggar

2

1906

Arthur J. Eames

1927

Elias J. Durand

3

1906

Lewis Knudson

1927

Beverly T. Galloway

1906

Lester W. Sharp

1927

William A. Kellerman

1906

Otis F. Curtis

1933

Charles F. Millspaugh

1906

William J. Robbins

1933

Williard W. Rowlee

1906

Loren C. Petry

1938

Mason B. Thomas

1906

Paul R. Burkholder

1944

William Trelease

1906

Adriance S. Foster

1944

Herbert J. Webber

2

1906

Barbara McClintock

1944

C. Stuart Gager

1910

Walter C. Muenscher

1944

_______________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

Table 4. Cornellians honored with Botanical Society of America Merit and Centennial Awards

(

http://botany.org/awards_grants/detail/bsamerit.php

).

Merit Awards:

George W. Beadle

1956

Bassett Maguire

1990

Benjamin M. Duggar

1956

W. Hardy Eshbaugh

1992

Arthur J. Eames

1956

Karl J. Niklas

1996

William J. Robbins

1956

Dominick J. Paolillo, Jr.

1998

Barbara McClintock

1957

Jack B. Fisher

2003

Lester W. Sharp

1958

William L. Crepet

2007

Loren C. Petry

1959

Walter C. Muenscher

1960

Centennial Awards:

Frederick C. Steward

1961

Marcus M. Rhoades

1962

W. Hardy Eshbaugh

2006

Jacob R. Schramm

1969

Jack B. Fisher

2006

Arthur W. Galston

1970

Karl J. Niklas

2006

Harlan P. Banks

1975

Dominick J. Paolillo, Jr.

2006

David W. Bierhorst

1979

Natalie W. Uhl

2006

_______________________________________________________________________________

101

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Table 5. Landmark Books in Botanical Sciences by Cornell Faculty in the Department of Botany

(1913-1964), New York State College of Agriculture.

SHARP, L.W. 1921 (1

st

ed.). Introduction to Cytology. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc. NY (2

nd

ed. 1926; 3

rd

ed.

1934)

MUENSCHER, W.C. 1922 (1

st

ed.). Keys to Woody Plants. Cornell Publications Printing Co., Ithaca, NY

(6

th

ed. 1950, expanded by E.A. Cope, 2001)

EAMES, A.J. and L.H. MacDANIELS. 1925 (1

st

ed.). An Introduction to Plant Anatomy. McGraw-Hill Book Co,

Inc. NY (2

nd

ed. 1947)

WIEGAND, K.M. and A.J. EAMES. 1925 (issued 1926). The Flora of the Cayuga Lake Basin. Cornell

University Agricultural Experiment Station Memoir 92. Ithaca, NY (Additions and Corrections 1939)

MUENSCHER, W.C. and L.C. PETRY. 1928 (1

st

ed.). Keys to Spring Plants. W.C. Muenscher, Ithaca, NY

(7

th

ed. ca. 1976)

MUENSCHER, W.C. 1935 (1

st

ed.). Weeds. The Macmillan Co. New York, NY (2

nd

ed. 1955, revised 1980,

with new forward and appendices by Peter A. Hyypio)

CURTIS, O.F. 1935 (1

st

ed.). The Translocation of Solutes in Plants. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc. NY

EAMES, A.J. 1936 (1

st

ed.). Morphology of Vascular Plants, Lower Groups. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc. NY

MUENSCHER, W.C. 1939 (1

st

ed.). Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Co. New York,

NY (revised ed. 1951)

SHARP, L.W. 1943 (1

st

ed.). Fundamentals of Cytology. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc. NY

CURTIS, O.F. & D.G. CLARK. 1950 (1

st

ed.). Introduction to Plant Physiology. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc.

NY

EAMES, A.J. 1961 (1

st

ed.). Morphology of the Angiosperms. McGraw-Hill Book Co, Inc. NY

KINGSBURY, J.M. 1964. Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada. Prentice-Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ

___________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

Table 6. Brief Chronology of Botany Departments & Herbaria at Cornell University (1868-1999)

1865

Cornell University, founded

1868

Cornell University, opened

1868

Original Department of Botany, Cornell University (1868-1922)

Albert N. Prentiss, Head (1868-1896)

George F. Atkinson, Head (1896-1918)

Willard W. Rowlee Head (1918-1922)

1870

Original Department of Botany Herbarium established, based on collections of Horace Mann, Jr.

1904

Cornell University College of Arts and Sciences established; Department of Botany, including its

herbarium, housed in this college

1904

New York State Legislature established the College of Agriculture at Cornell (1904),

L.H. Bailey, Dean (1903-1913), NYS College of Agriculture at Cornell (NYSCA)

1907

Department of Plant Breeding, established by Bailey

Department of Plant Physiology (1907-1912), established by Bailey

1913

Department of Botany (1913-1964), established by Bailey,

Karl M. Wiegand, Head (1913-1941)

Department of Plant Physiology fused with Department of Botany

1920s

College of Arts and Sciences Herbarium joined with NYSCA Department of Botany Herbarium

1935

L.H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium, established as an Independent unit of NYSCA

1951

Department of Botany herbarium named Wiegand Herbarium

1964

Division of Biological Sciences (DBS) (1964-1999), established within NYSCA

1965

Section of Genetics, Development and Physiology (GDP, 1965-1977; DBS)

Wiegand Herbarium (1965-1977) becomes Independent Unit within NYSCA, R.T. Clausen, Curator

Laboratory of Cell Physiology, Growth & Development (1965-1973) becomes Independent unit within NYSCA,

F.C. Steward, Head

1971

NYSCA renamed College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell (CALS)

1977

GDP name changed to Section of Botany, Genetics & Development (BGD, 1977-1980; DBS)

Bailey Hortorium and Wiegand Herbarium merge, become a unit within DBS/CALS (1977-1999)

1980

BGD name changed to Section of Plant Biology (1980-1999; DBS/CALS)

1999

DBS and all its sections DISSOLVED

DEPARTMENT OF PLANT BIOLOGY, CALS (formed from previous Section of Plant Biology &

joined with the L.H. Bailey Hortorium; W.L. Crepet, Chair)

____________________________________________________________________________________

102

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

The Struggle for Botany Majors

In the Fall Semester of 2001, when I became Chair

of the Department of Botany and Microbiology at the

University of Oklahoma, we had 11 Botany majors

(and 291 Microbiology majors). After a long

recruitment campaign, I’m happy to report that we

currently have 40 majors. In addition, we have

approximately 20 Botany minors who populate our

courses. While the number of Botany majors still

lags far behind that of Microbiology majors, I’m

proud of this accomplishment but worried about the

long-term future. In the next paragraphs I’ll outline

what I think has helped to increase the number of

Botany majors in our Department, but I don’t think

there is anything surprising about our recruitment

techniques—it’s essentially about being proactive

in engaging students multiple times in multiple

ways.

At the University of Oklahoma, there is no planned

Biology degree; students major in Botany,

Microbiology, or Zoology, although they can construct

an individualized Biology degree through the College

of Arts and Sciences (only a handful of students ever

use the individualized option). For years, we have

had to explain our (Botany’s) existence to the

Regents of the State of Oklahoma who monitor the

number of graduates in degree programs. While

our Department has produced enough Ph.D.s in

Botany to keep us out of the “low performance”

category, we haven’t had enough undergraduate

majors or Masters degree students to keep us from

having to report to the Regents about our attempts

to recruit students.

What wasn’t working in the past was an acceptance

of “the way it was.” Before I became Chair, if

students wanted to major in Botany, great; if they

didn’t, that was the way it was. As a consequence,

we had no formal activities to cultivate students who

expressed interest in Botany. Also, for many years,

when teaching assistants were assigned within

the Department, I would first let other faculty choose

graduate students they wanted as teaching

assistants in their class. For my Introductory Botany

course, I took the students who weren’t chosen.

While many of these students “last picked” were

good teaching assistants, many were not because

they had limited teaching experience or just weren’t

motivated or able to teach. Looking back, that

arrangement made no sense in terms of recruitment;

we were placing the best teaching assistants in

laboratories with only 2 or 3 students instead of our

basic class with hundreds of students (600-800

students per year). This Introductory Botany course

satisfies a general education requirement in

science (with a laboratory) but is also our “majors”

Botany class.

Now, as part of our overall recruiting effort, I pick the

TAs I think will best interact with undergraduate

students—those TAs who are interested in teaching

students and who might be good Botany

ambassadors and role models with whom younger

students can interact—and place them in the basic

Botany course. TAs are now challenged to find

students who would be good majors (based on

interest and performance) and are encouraged to

speak with undergrads on an individual basis about

majoring in Botany. In fact, I establish a “quota” for

all instructors in all our Introductory Botany

courses—I expect instructors to talk with students

who have shown some talent and interest in Botany.

For most of our faculty (and all of our grad students),

this was the first time they had ever thought about

recruiting students. Many faculty were clueless

about the need to recruit students to Botany; they

had little understanding about how faculty positions

at OU are awarded to those departments with high

student enrollments.

We are also fortunate to have a finishing graduate

student who is an excellent instructor and who really

enjoys working with undergrads. More importantly,

he is an advocate for Botany and a highly effective

recruiter for students who aren’t sure what major

they would like to choose. We have placed this

individual in basic lab courses and in our general

interest courses, and he has proven to be an

important source of new majors for us. In addition

to this grad student, we have been fortunate to have

three other TAs and two teaching postdoctoral

fellows who were excellent recruiters—much better

than faculty. These people are key to successful

recruiting because undergraduates interact with

them on a much more personal level than they do

with faculty.

As another part of our strategy for increasing majors,

we modified the requirements for our Botany major.

For years, we had been teaching several general

interest courses (Plant Care and Cultivation,

Ecology and Environmental Quality, and Economic

Botany). These are popular courses that students

often take as a second course in Botany after

gaining (or strengthening) their interest in plants in

our basic course. However, none of these popular

courses counted toward a Botany degree. In our

new major, all three courses can be applied for

major credit, however, students must still take

traditional, lab-based, hard-core Botany courses to

fulfill their degree (please see our website for

information about our major requirements). The

advantage is, of course, that students don’t feel that

they have wasted credit hours, and we capitalize on

engaging students when they are one step closer

to fulfilling degree requirements in Botany.

103

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

We also changed major support course

requirements for the major. We used to require our

students to take two semesters of physics, both four

hours. All of our students found these eight hours

to be very difficult and not particularly relevant to their

Botany coursework or careers. Students often

identified this two-semester series as one reason

they chose not to major in Botany or dropped out of

Botany. Botanists now require students to take one

course in physics and one of the following: a second

course in physics, a course in biochemistry, or a

course in statistics. This option has provided great

flexibility to our students who seem to appreciate

the choices and who can now choose a second

support course that may be more relevant to their

future work.

Because we had hundreds of students taking our

introductory Botany course each year, we had access

to a huge pool of potential majors and minors,

however, we never capitalized on this pool. We had

a minor in Botany in place for many years, but we

never emphasized it before. In hope of increasing

the number of students in our upper-division

classes, we now advertise and promote the minor

in all of our courses. Students who are “afraid” of

mathematics (and other support courses) but who

are interested in plants can receive a minor by

taking 15 hours of Botany classes, nine of which

have to be at the upper-division level. These students

help increase the size of our upper-division courses,

which are enjoying their largest enrollments in

many years.

The Botanical Society at OU is a student-run

organization of undergraduates (with some

graduate students) who are Botany majors, minors,

or other students interested in plants. Under the

guidance of two faculty mentors, we have re-

invigorated our Botanical Society, which now holds

monthly meetings, organizes field trips, grows plants

as a money-making project, and holds social events,

including semi-annual picnics at my house. These

activities are wonderful opportunities for students

to bond in a non-classroom setting and to meet

faculty in a relaxed environment, which, in turn,

benefits the students in the courses they are taking

together. We find that the social aspects of being a

Botany major are extremely important in keeping

students in our program.

My perception (based on anecdotal information) is

that students who have chosen to major in Botany

were already interested in the sciences but had

switched to Botany after considering other science

majors or teaching biology as a career, or they were

simply interested in plants and decided to major in

Botany because the courses they took confirmed

their interest. Students seem to respond very

favorably to attention, and our contact with them

became the “tipping point” in their decision to

become botanists. Overall, regardless of initial

student interest, it still takes tremendous effort to

recruit a student to major in Botany. We are constantly

encouraging students to take additional Botany

courses and to consider Botany as a major or

minor. But we are now actively engaged in the

process and no longer passively hoping that

students will come to us.

Unfortunately, we are moving into a new era at the

University of Oklahoma where students have several

alternative courses, including two new introductory

Biology courses, from which to choose for their

general education science requirement. This means

that fewer students will be directly exposed to plants

in an intensive and extensive manner in our general

Botany course. It remains to be seen how these

alternative courses will affect the recruitment of

future Botany majors. Wish us luck!

-Gordon Uno, Department of Botany and

Microbiology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK.

News from the Annual Meeting

Forum Keynote Address

Naturally Right by Design: Bring

Learning and School to Life

Stephanie Pace Marshall, President

Illinois Math and Science Academy

Dr. Marshall began her address by acknowledging

that while she is not a botanist, she has a love and

passion for mind-shaping and frequently uses

botanical metaphors. For instance, education is

like an aspen grove - - many seemingly independent

stems but all connected at the root. The root for

education is what we know about human learning

and how it is constructed. We learn by building upon

our prior knowledge and we must be cognizant of

this when we interact with student or the general

public. Our task, challenges Marshall, is to make

the story we know, botany, accessible to the public

and our students and to use it to design human

systems.

The story we tell about our science was the theme

of the rest of Marshall’s address. But first she

reminded us of what the ancient Greeks knew well.

Every story is really two stories. There is the overstory

- - the obvious plot (the facts we are trying to teach

or explain) and the understory - - the hidden and

mysterious, the implied. Furthermore, the understory

104

Plant Science Bulletin 53(3) 2007

is most powerful because it tells us how to feel