Plant Science Bulletin archiveIssue: 1970 v16 No 2 Summer

|

||||||||

|

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN |

|

|

ADOLPH HECHT, Editor |

|

|

EDITORIAL BOARD |

|

|

December 1970 Volume 16 |

Number Two |

The term spore has so many connotations in biology that its unqualified use might well be discontinued in a majority of instances in favor of, minimally, the terms mitospore or mciospore. This is, indeed, already the case in at least a few texts.

Many of our students complete an introductory botany or biology course and remain unaware of the correspondence, if not possible homology, of moss spores, fern spores, basidiospores, microspores, and megaspores. The common denominator here is that we are dealing with products of reduction division, or meiosis, i.e., with meiospores.

Similarly, students are apt to equate, for example, the so-called asexual spores, or mitospores, of Rhizopus and Penicillium, with moss, fern, and other meiospores.

A parallel situation pertains generally to the term sporangium. Compare, for example, the sporangium of Rhizopus with that of a fern. Or, for example, students may know that Peziza has an ascus, but do not know that the ascus is essentially a meiosporangium equivalent to that of mosses, ferns, and basidiomycetes.

The term prothallus is variously defined as: "the gametophyte of a vascular plant," and "the gametophyte of a pteridophyre." Some texts define and discuss the fern prothallus without mentioning gametophyte, and life cycle diagrams have a labelled sporophyte and a labelled prothallus. but the term gametophyte does not appear in the labelling.

The student is led to believe that fern life cycles have a prothallus, moss life cycles have a protonema, pine life cycles have a female gametophyte and a pollen grain, and angiospern life cycles have an embryo sac. The student is led to believe or he assumes that, in view of the differing terminology, these life cycles and structures are intrinsically different, and unrelated, special cases, and hence involve only rote memory, rather than basic patterns common to many organisms.

The terms homothallic and heterothallic were originally coined by Blakeslee (2) in his study of mating strains in Rhizopus early in the nineteen hundreds. A careful reading of his paper shows the bases for different interpretations in the meanings of these terms. In reference to heterothallic, for example, he wrote (2, p. 208) : "The condition is essentially similar to that in dioecious plants and animals." He then continues: "Inasmuch, however, as conjugation is possible only through the interaction of two differing thalli, we can express this fact by calling all species the sexual relations of which correspond to the Rhizopus type, heterothallic." Thus Blakeslee's emphasis is indeed on incompatibility due to distribution of sex organs on different thalli. In considering the term homothallic, Blakeslee uses Sporodinia as the type form. He places emphasis on self-compatibility due to a condition "comparable to hermaphrodites among the higher plants. Such forms may therefore be called homothallic."

Because Blakeslee seems to have neglected the possibility that "hermaphrodites among higher plants" may be either self-fertile or self-sterile, he paved the way for more than one interpretation of the terms he originated, and this is indeed what has occurred. For example, in defining heterothallic, Alexopoulos (1, p. 553) writes as follows: "According to one version: refers to a species consisting

3

of self-sterile (self-incompatible) individuals, requiring therefore the union of two compatible thalli for sexual re-production, regardless of the possible presence of both male and female organs on the same individual. According to another version: refers to a species in which the sexes are segregated in separate thalli, two different thalli being required for sexual reproduction."

The second version cited by Alexopoulos seems to con-form more closely to Blakeslee's original use of the term, i.e., heterothallic implies incompatibility due to distribution of sex organs rather than a self-compatibility even though both sex organs are present. The terminology re-quires clarification therefore to deal specifically with the two cases of "hermaphroditic" or "monoecious" individuals, those which are self-compatible and those which are self-incompatible.

Another outcome of Blakeslee's original paper has been the restriction imposed on the use of the terms homo- and heterothallic to those organisms "lacking distinguishable male and female gametangia" (7). Blakeslee himself with reference to Rhizopus wrote: "In this case the two complementary individuals which arc needed for sexual reproduction are not in general so conspicuously differentiated morphologically as in the higher forms," but, nevertheless, "such a morphological difference is often visible, and would undoubtedly be considered by systematists generally as an amply sufficient basis for their specific separation." Thus it seems to me that Blakeslee's original paper does not support the necessity for the restriction of isomorphism imposed by some authors.

In plant morphology there is at present an increasing emphasis on flagellation, in view of its presumed phylogenetic significance (6, 7). Some authors recognize three general types of flagella, as follows:

-

flagella lacking appendages: simple, whiplash or hair-less

-

flagella terminating in a short fibril: acronematic

-

flagella bearing lateral appendages.

At least one author equates the acronematic type with the first category of simple or whiplash. In this connection, Manton (6) questions the validity of the term acronematic, since the implication is that the terminal fibril is comparable to the laterals of the pantonematic type, which is, according to Manton, "in fact never the case." Faagellar appendages are themselves variously designated as (I) lateral fibrils, (2) flimmers, (3) mastigonemes, and (4) hairs.

In a detailed consideration of flagellar terminology, Manton states ". . . my own strong recommendation is to discard for the time being all special terms except perhaps the two oldest, Peitschengeissel (whiplash flagellum) and Flimmergeissel (hairy flagellum), limiting these however to the special case of the two differentiated members of a heterokont pair in the conventional heterokont groups." Manton warns of "premature systematization of nomenclature which can obscure genuine and phyletically significant differences under the artificial unity of a system of Latin names."

The designation testa is a minor but interesting ex-ample of the failure of a term to die. It is variously de-fined in different texts as: a seed coat, the seed coat, the outer seed coat, and the hard outer portion of the seed coat. One author additionally gives the synonymy: seed coats, testa or tegmen, and another states that if there are two seed coats, the inner is termed the tegmen.

A number of general botany texts omit the term. Others include it, in which case it is apt to appear in the index, glossary, and in the text, as is the case, for example, in a recently published botany text specifically designed for one semester.

Regardless of other considerations, it is interesting to note that the term testa is often and variously defined but seldom if ever used.

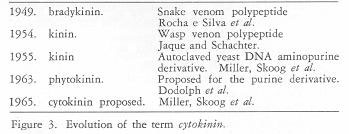

A few years ago I started to read an article entitled "kinins" (3), expecting to learn more about an aminopurine derivative which promotes cell division in plant tissues. Instead I found myself reading about blood- and tissue-produced polypeptides which influence smooth muscle action, blood vessel dilation, and sensitivity to cutaneous pain. I learned that these polypeptide kinins are also present in wasp and hornet venom.

The basis for my confusion is illustrated in Figure 3. In the steady flow of today's literature, it is difficult to be aware of all the terms which have been pre-empted in other areas. The sequence is an instructive example in the historical development of a particular term.

<left>

</left>

The term periplast is frequently defined as the usually flexible, limiting, sometimes rigid membrane around the protoplast of certain cell wall-free protists. The periplast is often considered as essentially equivalent to, or comparable to, the plasma membrane, as shown in the following definitions: "a complex, often ornamented plasma membrane"; "a living, clearly differentiated plasma membrane"; and "outer part of protoplast, comparable to the plasma membrane."

Whereas in some cases the term pellicle (in contrast to periplast) is explicitly defined as a "cuticle" or "exoskeleton," it is at other times considered synonymous to, and used interchangeably with, the term periplast.

The most frequent use of periplast in botany and plant morphology is in relation to Euglena. Yet the studies of Leedale (5), including electron microscopy, clearly indicate that the periplast is neither an exoskeleton nor a plasma membrane, but an essentially proteinaceous intracellular structure bounded externally by the plasma membrane.

According to Leedale (5, p. 96) : "the flat interlocking pellicular strips are intracellular structures lying immediately beneath the plasmalemma, a continuous tripartite membrane 80-100 Angstroms thick. The pellicle is not equivalent to the cell wall, since the latter is always laid down outside the plasmalemma." Nor is it equivalent to the plasma membrane, since (p. 99) : "the whole of the pellicular system lies within the plasma membrane."

4

Differences in definition or meaning of a term, as in this instance, may reflect problems of technique rather than of terminology per se.

The term umbel is variously defined in texts and in the literature as: (1) "a determinate inflorescence (basipetal or centrifugal maturation) ," and (2) "an indeterminate inflorescence (acropetal or centripetal maturation)."

The apparent contradiction is clarified by the following statement from Lawrence (4, p. 61-62) : ". . . in many cases the presumed distinction of an inflorescence being determinate or indeterminate is without validity .... For example, the umbel of members of the Umbelliferae is an indeterminate type whose outer flowers open before the inner ones. However, in many of the Amaryllidaceae (as in Allium) the umbel is a determinate inflorescence as indicated by the central flower opening prior to the outer flowers. Structurally, the inflorescence is an umbel in either family, but phyletically the two kinds of umbel are unrelated, and represent reduction by two different evolutionary lines."

I would not be in character if I did not have a term to add rather than to subtract or modify.

The majority of general botany (but not general biology) texts use and discuss the term and concept of in-florescence, e.g,, in considering raceme, umbel, and head: "The inflorescence characteristic of the Compositae, the head."

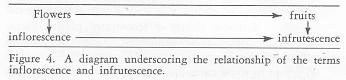

To my knowledge, the parallel and descriptive term, infrutescence, is not in general use. I find this term helpful in establishing developmental relationships and parallels, e.g., in considering: "the infrutescence which develops from the snapdragon raceme," "the multiple fruit, or infrutescence of pineapple," and "an ear of corn, or pistillate infrutescence."

The use of this term, as illustrated in Figure 4, would, I believe, underscore common denominators, as does the corresponding term, inflorescence, and would be preferable 'to "fruiting inflorescence" used in some texts.

<left>

</left>

In this paper and by these various examples I have at-tempted to illustrate some problems in botanical terminology, with special emphasis on how they relate to the teaching of undergraduate biology and botany courses.

In an effort to reduce the extent of these problems, and in addition to the proposals of Stein, already cited, I pro-pose:

-

the presentation of papers dealing in depth with specific terms or concepts before teaching and other AIBS sessions;

-

publication of these papers in Plant Science Bulletin, hopefully profiting from any discussion at the meetings or correspondence arising therefrom;

-

an appropriate individual, for example, the chair-man of the Teaching Section of the Botanical Society, or the editor of Plant Science Bulletin, could invite papers from one or more experts to discuss and more clearly delineare particular terms and/or concepts; such papers could be invited from authorities in other countries as well as our own;

-

periodic summaries of the status of specific terms could be published in BioScience, the American Biology Teacher, and similar journals, including their foreign and international counterparts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author wishes to express his appreciation to Dr. Gary Hillebrand, Dr. Frederick Truscott, and to the Editor of the Plant Science Bulletin for helpful suggestions received in the preparation of this paper.

LITERATURE CITED

-

Alexopoulos, C. J. 1962. Introductory Mycology. 2nd ed. Wiley and Sons, Inc.

-

Blakeslee, A. F. 1904. Sexual reproduction in the Mucorineae. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts & Sci. 40: 205-319.

-

Collier, H. O. J. 1962. Kinins. Sci. Am. 207 (2) : 111-118.

-

Lawrence, G. H. 1951. Taxonomy of Vascular Plants. Mac-Millan Co.

-

Leedale, G. F. 1967. Euglenoid Flagellates. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

-

Manton, I. 1965. Some Phyletic Implications of Flagellar

Structure in Plants. Adv. Bor. Res. 2: 1-34. Academic Press.

-

Scagel, F., Bandoni, R. et al., 1965. An Evolutionary Survey

of the Plant Kingdom. Wadsworth Publ. Co.

-

Stein, Howard J. 1965. Problems in Botanical Terminology: A Proposal. Pl. Sci. Bull. 11 (2) : 3-4.

-

Wolff, Emily T. 1965. Problems in Botanical Terminology (Continued) . Pl. Sci. Bull. 11 (3) : 8-9.

A Mature Stand of .Pines taeda Near Columbia, South Carolina

Richard Stalter Pfeiffer College

In recent years conservationists have become cognizant of the existence of an unusually large tract of nearly virgin bottomland timber lying within twenty miles of Columbia, South Carolina, in the Congaree swamp. This tract, containing 13,300 acres, is almost as wild and primitive as it was when the settlers first arrived in this region.

Little is known of this tract prior to the Civil War. Artifacts in fields on the south bank of the Congaree River and one or two Indian mounds in the nearby wooded swamps point to previous occupation by Indians ( John V. Dennis, personal communication, 1968). Also, several "cattle mounts" exist, one said by Dennis (1967) to contain several trees almost as large as those in the nearby forest. At the end of the Civil War the Beidler family bought part of the swamp; this part until 1905 was logged for cypress, representing an intrusion upon an otherwise virgin forest. In 1920 a hunting club acquired rights to the Beidler tract and much adjacent woodland, and maintains these rights today.

Efforts have been made to preserve this forest. In 1959 the National Park Service made a preliminary in-

5

vestigation of the Congaree swamp to ascertain its scenic, scientific, historical, and recreational values and recommended that an area of approximately 21,000 acres be set aside as a national monument. Owing to lack of popular support and Iand acquisition problems this recommendation has not prompted any action on the part of the Park Service (Dennis, 1967).

One of the most impressive sights in the swamp is the numerous large overmature loblolly pine (Pines taeda). Most of the trees are from 24 to 44 inches in diameter. Many of these trees appear very healthy and may live for another 50 years, as several of the oldest pine trees are 50 to 100 years older than the majority of the trees in the stand. Observations of borings and of the annual rings evident on the few cut pine trees indicate that most of the trees are from 100 to 175 years old; a few trees are even older. One giant with a DBH of 58 inches is estimated to be at least 250 years old.

That there is a paucity of pine stands such as this one can be seen by examining the work of Oosting (1942), and Ellerbe and Smith (1961). Oosting (1942) states, "That before this age (60 years) the trees (pine) can be used for lumber and, especially on good sites, lumbering or clear-cutting for cordwood is possible at a much earlier age. There are then . . . very few mature or over-mature stands."

Hopefully, concerned readers will write to biologists and congressmen in South Carolina asking for their consideration and cooperation toward enacting legislation to preserve this magnificent stand of pine.

LITERATURE CITED

Dennis, J. V. 1967. Woody plants of the Congaree forest swamp, South Carolina. Ecological Studies Leaflet No. 12: 35-42.

Ellerbe, C. M., and G. E. Smith, Jr. 1961. Soil survey interpretations for woodland conservation. 1:1-100.

Oosting, H. J. 1942. An ecological analysis of the plant communities of Piedmont, North Carolina. Amer. Midl. Nat.

25:1-126.

Quo Vadis, Botanicum? Procede, Terge!

Ralph W. Lewis

Department of Natural Science Michigan State University

As a beginning teacher of freshman botany thirty-five years ago, I asked myself the title question many times. For years I searched for answers in botany and in the history and philosophy of science in general. My answer, "Forward, Onward," stands out clearly and forcefully in light of the findings of my search. But many botanists, and many biologists, will not like what I found in my search because I found a beautiful discipline being inefficiently presented without the intellectual excitement that accompanied the

growth of the discipline.

In a few paragraphs I can only sketch or hint at the basis of my optimism and my disgruntled view of the presentation of our discipline. But if readers take me to task, support from specific examples can be quickly mustered and presented.

A discipline in the sciences is determined by: 1) a group of intellectual constructs (mostly theories and relational laws), 2) facts subsumed by the constructs, 3) intellectual activity associated with established constructs and with the discovery of new constructs, 4) experimental and observational activity designed to clarify, to extend, or to define the limits of established constructs or designed to test nascent constructs, and 5) other miscellaneous knowledge.

For the moment accept this definition of a science discipline and then enumerate the theories and relational laws that guide our professional thinking. Do you not find that, with few exceptions, every major theory and law in botany is a major theory and law in zoology? Thus in one sense both botany and zoology are dead. They are unified in one discipline—biology.

Since I accept this view of botany, how can I be so optimistic about the future of botany? How can I say, "Botany, forward, onward!"? It is simple—1) by defining botany as the study of plants in the context of biology, 2) by knowing the history of the development of biology and by knowing the numerous and crucial contributions of botany to that development, and 3) by knowing about the many, many recent advances that have come and are coming from the study of plants.

Despite their unity in one discipline, both botany and zoology are more alive than at any earlier time. Wherever I look at the advancing front of biology, whether it be in evolution, ecology, differentiation, genetics, molecular ecology, or any of the aspects of molecular biology, I find men who study plants making superb contributions. This is botany at work. True, many of the men doing the work do not call themselves botanists. But why worry about this? This is in the tradition of botany. Were not many of the outstanding botanists of earlier times medical doctors, chemists, booksellers, or the like? Was not Linnaeus also a zoologist?

Some botanists and zoologists worry about their elementary course being replaced by a biology course. This change is probably inevitable because of the growth of unifying constructs. But this trend could be countered in institutions where there are a large number of majors in the plant sciences by offering a course in plant biology. The general topics would be the same as in a regular biology course with most, not all, of the illustrative material drawn from botany. This would permit a more rapid advance of students in their study of plants without loss of a general understanding of the parent discipline, biology.

Some botanists worry about being combined in the same department with zoologists. When this occurs botany will not be swamped if botanists bring to the situation the knowledge, the vigor, and the intellectual activity which made botany a leader and an innovator in the construction of much of today's biology. However, if the combination occurs and brings together men who are ignorant of the

6

unity of botany and zoology, nothing much can be done to save the situation because it is already lost.

Botany, the study of plants, has before it a magnificent future. But it will not be a future of static descriptive botany such as I was taught. Rather it will be concerned with facts in relation to ideas—the concern that contains the active intellectual component of the discipline. Darwin said, "Facts to be of any service must be for or against some view." C. E. Bessey (Ann. Mo. Bot. Garden 2:110. 1915) said, ". . . one can go but a short distance indeed in any science without finding it necessary to erect a speculative framework upon which to arrange his observed facts." If the words of these exceptional men are heeded so that botanical teaching and research constantly display the excitement of intellectual activity as facts and speculations interact in thought, botany will move forward with increasing success.

NOTES FROM THE- EDITOR

Individual members as well as libraries have at times been puzzled about the number of issues of the Plant Science Bulletin that have appeared each year. We have currently settled to a pattern of four issues per annual volume, and this has been the pattern for all but five previous years, as follows: Vol. 4 (1958), 6 numbers; Vol. 5 (1959), 5 numbers; Vol. 6 (1960), 5 numbers; Vol. 10 (1964), 1 number; Vol. I] (1965), 3 numbers.

In this column of our last issue your attention was called to the appointment of a committee to nominate a person to serve as Editor of the Plant Science Bulletin for the five-year term beginning in 1971. Please send any suggestions you may have to one of the members of this committee: William L. Stern, University of Maryland; William T. Jackson, Dartmouth College; and Adolph Hecht (chairman), Washington State University.

NEWS AND NOTES

Major Evolutionary Events and the Geological-Record of Plants

Proceedings of a symposium with this title, held at the 11th International Botanical Congress, Seattle, 1.969, are expected to appear in the July number of Biological Re-views (Cambridge, England), and will include the complete symposium, with illustrations and tables. Among the papers included are those by J. W. Schopf on the Precambrian; W. G. Chaloner on early Devonian; C. B. Beck on later Devonian events such as origin of the secondary body; J. M. Pettitt on the origin of the seed; and J. Muller on palynological evidence of the origin of angiosperms. Separate copies of this number of the Journal will be printed and sold, but the Editor would like a clue as to the number needed. Dr. Harlan P. Banks, 214 Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. 14850, has offered to collect this information for the Editor of Biological Reviews; please let Dr. Banks know of your interest in purchasing a copy (copies) of this publication.

Plant Systematics in Canada

The Mycology and Vascular Plant Taxonomy sections of the Canada Department of Agriculture's Plant Research Institute have recently moved into a newly renovated and remodelled building on the "Central Experimental Farm" Campus in Ottawa. The dedication ceremonies and reception, held on March 19, 1970, were attended by some 200 visitors. Mr. S. G. Shetler, Associate Curator, Division of Phanerogams, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, and Secretary of the Flora North America project, gave a special seminar on "Biosystematics in the Computer Age."

The new accommodation brings together the two parts of the Canada Department of Agriculture's research pro-gram in systematics with a staff of 24 research scientists engaged in taxonomic, biosystematic, and evolutionary studies on fungi and higher plants. The National Mycological Herbarium (DAOM—170,000 specimens) and the Vascular Plant Herbarium (DAO-562,000 specimens) along with the fine taxonomic library have been brought together under one roof, providing an excellent systematics research facility not only for the staff of the Department of Agriculture but also for visiting biologists from elsewhere in Canada and throughout the world.

American Quaternary Association

The newly organized American Quaternary Association (AMQUA) will hold its first national meeting in 1970. The meeting will be held in Yellowstone National Park and at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana, from Friday evening, August 28 through Tuesday evening, September 1. The meeting will include two days of field conferences, with discussions on broad topics of general interest illustrated by the Quaternary features in and around Yellowstone Park and Bozeman, and two days de-voted to a symposium and sessions of papers on "Climatic Changes from 14,000 to 9,000 Years Ago."

Further information can be obtained from the AMQUA Secretary, Margaret Davis, Great Lakes Research Division, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104.

Balanced Biology Programs in Community Colleges

The Teaching Section of the Botanical Society of America and the AIBS Office of Biological Education will jointly sponsor a symposium, "The Development of Balanced Biology Programs in Community Colleges," which will be held on August 26, 1970, 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon, in conjunction with the AIBS meetings at Indiana University. Dr. Irving Knobloch of Michigan State University will serve as chairman of this symposium. The program is as follows:

-

Dimensions of the Problem: Is There any Botany in the Two-Year College?

Dr. O. J. Eigsti

Chicago State College

Chicago, Illinois

-

Models for the Integration of Botany in the Biology Program of Two-Year Colleges

Dr. Willis Herzig

West Virginia University

Morgantown, West Virginia

III. Expanding Plant Sciences in the Two-Year Colleges Mr. Robert Gillespie

Meremac Community College

Kirkwood, Missouri

7

-

Responsibilities of the University in Providing Trained Botanists for Undergraduate Education

Dr. William Stern

University of Maryland

College Park, Maryland

-

How Can OBE Be Helpful in the Development of Balanced Biology Programs?

Dr. Elwood B. Ehrle

AIRS Office of Biological Education

Washington, D.C.

-

Discussion

Proposals for Use of the R/V ALPHA HELIX

The R/V ALPHA HELIX, designed and built as a floating laboratory for experimental biology, will be made available for half of each year for 1970, 1971, and 1.972 for short cruises for biological oceanographic research that is suited to its facilities.

The distinct possibility exists that the National Science Foundation will grant support for operation of the vessel for the second half of these calendar years for biological oceanography. The support would come from research funds, but cruises that include an element of graduate student training or for advanced predoctoral research will be considered. The support is expected to be only for ship time; Scripps Institution of Oceanography will have no funds for travel to or from the ship or for direct scientific costs. It may in some cases be able to provide equipment not normally carried by the ALPHA HELIX.

Cruises will generally be between two days and two weeks in the eastern Pacific north of the equator. Projects proposed may include from one to ten persons in the scientific party.

Proposals should be sent to the Director, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Those for July-December, 1970 that have been received up to April 15 will be considered together. For 1971 and 1972 proposals should be received by January 15, 1971 and 1972, respectively. The National Advisory Board for the R/V ALPHA HELIX will select programs from those submitted on the basis of scientific merit, justification for the ALPHA HELIX, and compatibility with other programs.

The vessel may be outward bound for Antarctica for the austral summer of 1970-71 (passing near or through interesting areas such as the Costa Rica Dome and the Cromwell current) and north bound from the Palmer Peninsula to the Marshall Islands in March (traversing areas little known biologically). Proposals for observations or sampling during these transits are in order.

Book Reviews

HARDIN, J. W., AND J. M. ARENA. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 1969. 167 pages, 55 illus. $6.00.

This interesting book is concerned with the common native and introduced plants of the United States (including Alaska and Hawaii) and Canada that may cause poisoning in humans. Plants are treated that cause allergies or allergic reactions and dermatitis or skin irritations as well as those that cause poisoning as a result of inges-

tion. Several facets of this book make it valuable for those who need a summary of such information. This is especially true since almost all previous literature on poisonous plants has been oriented toward those plants that are poisonous to livestock. Information is given for most of the plants on their description, distribution, and toxicity, and in the event of poisoning the symptoms and treatment of humans. The entire coverage appears quite adequate especially as the book was written by a team composed of a plant taxonomist and a pediatrician, both of whom have previously published bulletins and papers on poisoning and poisonous plants. The authors have combined experiences with poisonous plants from the field, laboratory and clinic, and information from the herbarium and library. Certainly one of the highlights of this book must be the inclusion of many ornamental plants that are poisonous. In this group there are house-plants of the cooler regions such as Philodendron spp. and Euphorbia spp., as well as many ornamental shrubs and herbs of the warmer parts of the United States. The Iisting of several hallucinogenic plants such as nutmeg, peyote and marijuana is particularly timely. An especially valuable photograph of the notorious jequirity pea (Abrus psecatorius) is provided. Equally useful are the ways to prevent plant poisoning, a section on first aid, a list of poisonous and non-poisonous berries, a number of general references, and many good illustrations.

I have only a few minor criticisms of the work. Recommendations on the treatment of dermatitis caused by plants were omitted, and these would have been most useful. Suggestions should have been included on how to distinguish between poison sumac (Toxicodendron ves-nix) and the non-poisonous sumacs (Rhos spp.). The two full pages of photographs of pokeweed (Phytolacca) could have been reduced to one page. Additional photographs or line drawings of a few more of the common trouble-some plants would have been useful. An illustration of a plant more likely to cause poisoning directly in humans could have been used instead of the drawing of corn cockle (Agrostemma githago) which is a weed of grain fields. Perhaps some mention should have been made of the recent and extremely dangerous use of Datura to pro-duce hallucinations. Likewise omitted was reference to the occasional but apparently safe use of the ripe fruits of, the well known "wonderbcrry" (Solanum busbankii?) in pies. All of these criticisms are very minor in comparison with the many valuable facets of this book. In all, this book is well and interestingly written in a clearly organized format.

Samuel B. Jones, Jr.

WHEELER, B. E. J. An Introduction to Plant Diseases. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., London. 1969. ix + 374 pp. $12.75.

This book is basically organized around types of diseases, i.e., general kinds of diseases are discussed together regardless of their causes. For example, the chapter entitled "Wilts" deals with diseases caused by various fungi, bacteria, parasitic phanerogams, and even insects. In addition to fifteen chapters so organized, there is an introduction

8

and five chapters dealing specifically with disease assessments and control principles. The approach is different and commendable. However, certain chapters, or parts of chapters, are uneven in quality and potential usefulness in the classroom.

Some specific examples of likes and dislikes are as follows. In the introductory chapter definitions and concepts are given rather briefly and with little discussion. Indeed, it will be difficult for some students to "pick out" important terms. It would have been useful to italicize such terms as "infection," etc. In the chapter on damping off and seedling blights it is said that Pythium species "reproduce by sporangia and oospores," but the student is told little more about these structures. Similar cases of unexplained terminology and concepts are found in most chapters. The chapter on root and foot rots is accurate, but very general; not enough is mentioned concerning basic concepts. However, in the same chapter, the short portion on "control" seems excellent. In the chapter on "Wilts" almost nothing is said about the mechanics whereby causal organisms accomplish wilting. The chapter on powdery mildews seems quite good, except that the more recent studies (ultrastructure of haustoria, etc.) could have been cited. The same chapter does include some of the most beautifully executed drawings of erysiphaceous ascigerous stages that I have seen. The chapter dealing with rust diseases omits much on the cytology, genetics, and physiology of rust fungi and their hosts. One must arrive at chapter 11, "Leaf Spots," before the Fungi Imperfecti are clearly defined, even though pre-ceding chapters deal with many diseases caused by Deuteromycetes. The latter chapters concerning disease assessment and control seem good, excepting chapter 21 which deals with breeding resistant varieties. That chapter is so brief and incomplete that it serves no purpose; it should not have been included.

This book is recommended to teachers who primarily emphasize disease symptoms. Teachers who emphasize interactions between host and causal agent and who stress the mechanics of disease development will probably choose from among other extant textbooks.

Jack_D. Rogers

OLBY, ROBERT C. Origins of Mendelism. - Schocken, New York, 1969. 204 pp. illus. paper $2.45.

The centennial observance of the first publication of what we know as Mendel's Laws stimulated the publication of many volumes on Mendel and the science he helped develop. It is now known that all of Mendel's discoveries had been made earlier, but no one had put all the discoveries together nor seen their significance as Mendel did. Robert C. Olby, a librarian of the Botany School, Oxford, England, describes enthusiastically the growth of ideas about inheritance and variation which preceded Mendel. The book was originally published in 1966 by Schocken and is now released as a paperback.

Origins of Mendelism may be divided into three sections, of two chapters in each section. The first section deals with the pre-Mendelian hybridists, the second with

Mendel's contemporaries, and the third with Mendel and the rediscovery of his findings. The pre-Mendelian hybridists are treated with the greatest depth and perception. Interactions between Koelreuter and Linnaeus over whether hybrids were new true breeding species are vividly de-scribed. The flowering of Koelreuter's Nicotiana hybrids in the spring of 1761 has great significance when placed by the author in this context of eighteenth-century scientific thought. Parr of the depth of this section may be attributed to the research by the author in preparing a biographical essay on Koelreuter, which was also published in 1966 .as part of a book on late eighteenth-century European scientists. This section alone is worth the price of the book.

The two chapters on Mendel's contemporaries contain less detail. Even here, however, the thrill of development and discovery is conveyed by the author. The reader follows a thread of reasoning which might well have occurred in the minds of scientists. One begins to understand the confusion of such scientists as Naudin, Galton, and Darwin in trying to explain the many varieties of results from hybridization experiments involving genic interaction, pseudogamy, and polyploidy when complicated by somatic mutations and viral infections. The highlight of this section is an examination of the correspondence between Galton and Darwin which indicates that Galton had worked out the Mendelian explanation of hybridization but never demonstrated it. Olby raises the question of what Darwin's response might have been had he not been influenced by his own theory of pangenesis.

The last two chapters of the book may appear to some as afterthoughts but they are necessary to show the fruition of the preceding century's growth. Gregor Mendel's life is briefly sketched and the report of his correspondence with Naegeli over the then confusing results of apomixis in Hieraciumn emphasizes his brilliance as an experimentalist. Olby reconstructs the events which led to the re-discovery of Mendel's Laws, noting the contributions of the cytologists, Weismann and Flemming, in preparing the basis for de Vries' independent discovery of Mendelian ratios. He postulates that de Vries had known of Mendel in 1896 or 1897 but underestimated the significance of Mendel's work compared to his own which had the additional cytological backing.

This informative book is easy reading and a necessary addition to every scientific library. The author's use of extensive notes and bibliography at the end of each chap-ter and the inclusion in the appendices of some of the original writings of the scientists mentioned in the chapters makes the book even more valuable to the student.

John M. Hill

O'BRIEN, T. P., AND MARGARET E. MCCULLY. Plant Structure and Development. A Pictorial and Physiological Approach. The Macmillan Company, New York, 1969. 114 pp. $9.95 hardbound, $5.50 paper-back.

This book should be a welcome addition to the library of instructors and students in modern biology or botany courses. An understanding of structure and function in-

9

vests each field with increased significance, and this book attempts to relate the two. This book presents a large number of light- and electron micrographs to illustrate the brief text descriptions. As is necessary in so few pages, many exceptions or deviations from those illustrated or described arc omitted, and one interested in greater depth should be prepared to make frequent use of plant anatomy or plant physiology books to supplement the material in Plant Structure and Development. For those who wish to study further, the list of general references, reviews, and research papers at the end of each section adds much to the value of the book.

Perhaps the strongest contribution that this book makes is a result of liberal use of many light micrographs to enable one to make the tremendous leap from unaided-eye observations to the wealth of detail characteristic of an electron micrograph. The beginner, or even the expert on another plant or organ, can feel lost when faced abruptly with unfamiliar territory unless orientation is provided.

The first section deals with "The Cell" and provides one of very few chapters in any textbook that is specific for plant cells. The brief paragraph on plastids is remedied somewhat by material on chloroplasts in the section on leaves. The second section on "Cell Production: Mitosis" is beautifully illustrated, and to some extent these illustrations offset the brief text descriptions. The next three sections on "The Root," "The Shoot Apex and Leaf Initiation," and "The Leaf" are again very brief and, I think, should be supplemented by other references to pre-vent one from assuming that the material presented is in any way exhaustive. Section 6 on "Buds" is the most in-complete of any section and presents little information beyond what one would find in a college freshman botany book. Section 7 on "The Stem" is illustrated with four light micrographs in color and is one of the more fully developed sections. In section 8 on "The Reproductive Tissue" the scanning electron micrographs and text material on pollen are a definite improvement over treatments of the subject one usually encounters. The last section (9) on "The Seed" is less than five pages and much too brief to give one an appreciation for the large variation present in seeds of various species. The appendix, giving some technical details on light micrography and some staining techniques, is only two pages long but useful.

L. K. Shumway

STREETS, RUBERT BURLEY, SR. Diseases of the Cultivated Plants of the Southwest. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona, 1969. 390 pp. $9.50.

Although written as a compendium of plant diseases in the southwestern U.S.A., this book could be entitled, "Manual of Plant Diseases of the Semi-arid Environment." Using an informal approach, and drawing on forty-three years of experience as a teacher and practitioner of plant pathology in Arizona, the author lists, briefly discusses, and, in many cases illustrates, parasitic and nonparasitic diseases of about 275 cultivated plant species and varieties. The twenty-eight chapters are grouped under seven sections, the first of which deals specifically with the semi-arid environment and its effect on plants as well as plant diseases. The remaining sections are by plant category and range from

"Diseases of Field Crops" to "Diseases of Cacti, Other Native Plants and Greenhouse Plants." The appendix includes a handy list of conversion factors (units of measure, rates of application for agricultural chemicals, etc.) and a list of common and scientific names of host plants. The index is conveniently divided into I, Host Names and Diseases, and II, Causal Organisms and Agents.

The book is intended and well suited for use by ex-tension, agribusiness, botanical garden, nursery, and lay personnel. It is further intended for the classroom as a supplement to current texts. The author has avoided an intentional focus on basic concepts and principles of plant pathology, mechanisms of pathogenesis, and definition of terms, and, instead, has concentrated on etiology, symptoms, and control of a systematic listing of plant diseases. His choice of terms is designed to reach the laity as well as the professional plant pathologist. By recording more than four decades of personal observations and records of plant diseases of the southwest, Dr. Streets has indeed per-formed a service to botany, plant pathology, and agriculture.

R. James Cook

SEIKEL, MARGARET K., AND V. C. RUNECKLES (Editors).

Recent Advances in Phytochemistry, Volume 2. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York. 1969. 175 pp. $9.75.

This second volume of a series, designed to present a critical survey of current research in the expanding field of plant chemistry, serves well this purpose. The articles are all informative, timely, and useful to the research scientist interested in learning the fundamentals of the topics covered. Chapter 1, by J. J. Katz and H. C. Crespi, de-scribes new applications of nuclear magnetic resonance to the study of isotope effects in plants. Chapter 4, by A. M. Duffield, discusses the new uses of mass spectrometry in the field of natural product chemistry, particularly sterols. Chapter 5, by E. von Rudloff, describes the use of gas chromatography for chemosystematic studies with terpenes. Chapters 2 and 3 blend this volume with reviews of recent advances and techniques in the fields of lignin chemistry by J. M. Harkin and plant tissue culture by E. J. Staba.

This volume is not only valuable as a concise introduction into the scope of usefulness and limitations of the methods and techniques, but as an introduction to the kinds of elegant research that are possible using these approaches.

C. A. Ryan

LAMB, EDGAR, AND BRIAN LAMB. The Pocket Encyclopedia of Cacti and Succulents In Color. Blanford Press Ltd., London, 1969. First American Edition, Macmillan, New York, 1970. 217 pp + 326 color photo-graphs + 21 figures. $4.95.

Most of this book (pages 49 through 160) consists of excellent colored photographs of cacti, succulents, and related plants of dry habitats. Thirty pages of descriptions of the species that are illustrated follow these pages of photo-graphs. The remaining sections of the book are concerned largely with procedures and advice about growing these plants. The principal chapters are on soil mixtures, con-

10

tainers, water management, pests and diseases, greenhouse culture, outdoor culture in warm climates, vegetative propagation and grafting, and growing the plants from seed. The volume is concluded with an index to species, genera, and descriptive topics; the index includes separate references to each of the 326 colored plates.

Adolph Hecht

HUTCHINSON, J. Evolution and Phylogeny of Flowering Plants. Dicotyledons: Facts and Theory. Academic Press, London and New York, 1969. .717 pp., illus. $25.00.

One turns to this "Companion or Supplement" to Dr. Hutchinson's "Families of Flowering Plants, 2nd Ed., Vol. I, Dicotyledons" with great hopes that it will provide the rationale in some detail for the author's often extraordinary groupings of families and orders of dicotyledons. Unfortunately, these hopes are soon deflated. Although considerable fascinating detail, generously extended with many original drawings, is supplied for critical or unusual genera in many families, little evidence is presented to explain or justify the Hutchinsonian arrangements and suggested relationships. The author does in his preface note that much of the phylogeny of each order has been taken from the early English botanist Lindley.

At least two new families of angiosperms have been established in this book. The tribe Salpiglossideae of the Scrophulariaceae has been promoted to the Salpiglossidaceae; and two specialized herbaceous genera of Capparidaceae, Oxystylis Torr. & Frem. and Wislizenia Engelm., have been segregated as the Oxystylidaceae. Both families seem quite unwarranted. In attempting to under-stand Dr. Hutchinson's penchant for taxonomic inflation in some families, the following quotations may be revealing. In regard to recognizing the celastraceous genus Goupia as a distinct family, he comments that, "If only on account of these diverse views it seems better to regard it as a separate family." He petulantly disposes of possible criticism of his treatment of the Hypericoideae as a family distinct from the Clusiaceae by grumbling, "But taxonomic botanists, especially beginners fresh from college, are some-times apt to differ from established authority, thereby at times revealing their ignorance or immature judgment." Many of us not so fresh from college would be forced to join the youngsters here, no doubt revealing otir immature judgment and disrespect for established authority. Calling upon authority, no matter how firmly established, is seldom ever, and especially today, an adequate substitute for solid evidence rationally presented. The failure of the Hutchinsonian system to gain wide recognition in the botanical world is possibly due in large extent to the author's continued refusal to "put his cards on the table."

As usual with Dr. Hutchinson's monumental efforts, there is much to be praised in this book. It is Iucidly written and beautifully illustrated. The author's vast, if somewhat imperfect, knowledge of the families and genera of dicots is obvious on every page. He has supplied many maps to show the discontinuous distribution of various wide-ranging genera or families, apparently mostly selected to support his belief in relatively recent continental drift. The variation in fruit types, as in the Leguminales, Brassicaceae, and Apiaceae, and in certain other critical reproductive organs is shown in generous detail for selected large families. The exceptional and largely obsolescent family names like Guttiferae, Compositae, and Labiatae have uniformly been replaced by those based upon type genera, as Clusiaceae, Asteraceae, and Lamiaceae. The author, finally, has the courage to flush out the abundance of factual information with both phylogenetic and biogeographic speculation, which, whether one agrees with it or not, certainly arouses the reader's interest.

The arrangement of families in this book is essentially that found in "Families of Flowering Plants, 2nd Ed., Vol. I, Dicotyledons," published by Dr. Hutchinson in 1959. Be-cause of my probable bias in phylogenetic matters, I prefer not to comment upon the phylogeny presented in this and the author's other books further than to express my regret that the author still continues to ignore generally the often highly suggestive and useful information presented abundantly by the wood anatomists, palynologists, cytotaxonomists, chemotaxonomists, and other comparative systematists. For example, in maintaining the South African Heteropyxis as a separate family near the Rhamnaceae, he ignores the definitive paper of Dr. W. L. Stern showing that the genus is an African outlier of the Australian Leptospermoideae of the Myrraceae. Eames and McDaniels long ago adequately proved that the fleshy parse of the pome is largely floral tube, not receptacle. Dr. Hutchinson's repeated use of the phrase "dioecious flowers" is most inaccurate and distracting. Flowers cannot be dioecious or monoecious; they are perfect or imperfect, bisexual or unisexual. Species, if they bear unisexual flowers, are dioecious, monoecious, or polygamous.

Instead of discussing phylogeny, I prefer to examine some of the factual material. The author is often careless with his facts, particularly those having to do with geography and plant distribution. He is especially weak in American geography, flora, and history. My home state of Florida, at most only a few million years raised from the sea-bed and not raised far at that, is hardly an "ancient piece of land." The dwarf oaks pictured for the Florida Keys are found only in sandy barrens mostly in the central part of the Florida peninsula. Leitneria occurs in fresh-water, not saline, swamps in the southeastern United States. Parthenocissus tricuspidata Planch. is Boston-ivy; P. quinquefolia Planch. is the Virginia Creeper. They are quite distinct species from different continents. The accepted name for the American Slippery Elm is Ulmus rubra Muhl., not U. fulva Michx. Benjamin Franklin, remembered botanically by the beautiful Franklinia Bartr. ex Marshall, though a great and wise American printer, publisher, author, scientist, diplomat, public servant, and founding father, was never a president of the United States of America.

Dr. Hutchinson is somewhat remiss in his geography for other parts of the world also. Laportea gigas Wedd., now called Dendrocnide excelsa (Wedd.) Chew, is a giant stinging tree of eastern Australia, not of Polynesia, and it can attain heights of 30 to 35 meters. Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. is indeed known in the wild state in the mountains of central China. Embothriunt is monotypic and restricted to southern South America; Oreocallis is the proteaceous

11

genus found in both South America and eastern Australia and New Guinea. Daphoiphyllunt reaches not only Timor but New Guinea as well. Not only Ostrearia but also Neostrearia of the Hamamelidaceae occur in Australia. Eupomatia is not confined to eastern Australia for it is found also in New Guinea. Similarly, Balanops, better treated as one genus, is found in Fiji as well as in New Caledonia and northern Queensland. Galbulimima is the correct name for the single genus of the Himantandraceae, and a recently published study indicates that the two or three species" are really only one. Fagus is not found in the Andes nor elsewhere in South America as a native plant. Crossosoma is not monotypic but has two rather dissimilar species, C. californicunz Nutt., restricted to the islands off the coasts of southern and Baja California, and C. bigelovii S. Wats., of rocky desert canyons of the Southwest.

In addition to numerous errors of fact, there are unfortunate omissions, as in the table differentiating the Apiaceae from the Araliaceae. The author neglects therein to mention that there are herbaceous araliads and woody apiads and that there are mericarps among the Araliaceae, as in the New Caledonian Myodocarpus. He confines Licania of the Chrysobalanaceae to tropical America, but there are at least four species of the genus known from New Caledonia. On the other hand, he claims Hamamelis as the only hamamelidaceous genus to be found in both the eastern United States and eastern Asia; surely Liquidambar deserves mention here too. The Saurauiaceae are not confined to Asia; Saurauia is heavily represented in tropical America and Australasia as well as in eastern Asia. In addition to the species of Fuchsia in America and New Zealand, there is a rare species in Tahiti. Vacciniunz, listed as rarely epiphytic, has, like Rhododendron, many epiphytic species in the highlands of New Guinea. In describing northern hemisphere Rhamnaceae as hum-drum Rhamnus-types, Dr. Hutchinson has apparently for-gotten the varied and beautiful Ceanothus species of west-ern North America. The Rutaceae are represented by more than the small tribe Ruteae in the north temperate parts of the world. The author might have mentioned Choisga Kunth, Cneoridium Hook. f., Esenbeckia H. B. K., Phellodendron Rupr., Ptelea L., and Zanthoxylum L. among others. Tropaeolunz is not the sole member of the Tropaeolaceae; the family is also represented by Magallana.

Like many British and other European authors, Dr. Hutchinson likes to present his distribution maps with Europe and Africa centrally placed, presumably because the prime meridian runs through Greenwich, England. This is unfortunate for illustrating the distribution of many wide-ranging taxa, as in his maps of Anaxagorea, Pachysandra, Enzbothrium (Oreocallis) , Caulophyllum, Lardizabalaceae, and Fuchsia, wherein the Pacific Ocean deserves central placement. His map of Coriaria rusci f olia L. and C. thyzni f olia H. B. K., really only one species, points not to a former land connection between the Andes and New Zealand, but to relatively recent long-distance dispersal of the fleshy fruits by birds.

Considering the price of this expensive tome, the editors could well have afforded to hire an expert plant geographer and taxonomist or two to check the factual content of the text. It is to be hoped that any future printing of

this volume will correct the many errors and omissions, of which only a sample has been listed here. Robert F. Thorne

LAWRENCE, GEORGE H. M., A. F. GUNTHER BUCHHEIM, GILBERT S. DANIELS, AND HELMUT DOLEZAL, editors. B-P-H, Botanico-Periodicum-Huntianum. 1063 pp. Hunt Botanical Library, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1968. $30.00.

For years botanists have struggled with the Union List of Serials and similar library reference books in tedious searches for the full title of an obscurely cited journal in order to locate a seemingly important publication. The B-P-H, as the editors designate it, has gone a long way toward relieving the pain of such searches by listing many different ways that a journal has been cited, even through name changes, and by listing the location of the entry in the Union List of Serials. Each abbreviation listed is cross-referenced to a recommended abbreviation followed by a concise statement of the title in full, changes in name and numbering of volumes, original place of publication, the number of volumes published, and years of publication. More than 12,000 titles are provided with recommended abbreviations and descriptions including "not only botanical periodicals per se, but also those that are only partly botanical in scope, e.g., those dealing with agriculture, agronomy, bacteriology, biology, ecology, floriculture, forestry, fruit growing, genetics and plant breeding, geography, horticulture, hydrobiology and limnology, microbiology and microscopy, paleontology, pharmacology and pharmacognosy, plant pathology, and vegetable crops." Taxonomists, especially, will be pleased that special attention has been given periodicals containing new taxa, even to the level of cultivars. However, environmental biologists, physiologists, and applied scientists should not despair because their interests also have been considered carefully and they will find the B-P-H as helpful to them as to the taxonomist.

The introduction explains the manner in which the citations are drawn up, the rules followed for development of abbreviations, the handling of synonymous abbreviations, and the system of transliterating non-roman languages. .

Two appendices, comprising pages 1005-1063, complement the introduction. Appendix I lists words or abbreviations of words used in B-P-H abbreviations in much greater (and hence more useful) detail than in the widely used Style Manual for Biological Journals published by the American Institute of Biological Sciences. It is clear that great effort has been dedicated to development of suitably unambiguous titles, but some recommendations will doubtless be ignored initially. As abbreviations used by most botanists are included in the Periodical Listing, this appendix may seem superfluous but many ephemeral government leaflets, congress publications, and newly created serials not listed may be cited in botanical publications. The breadth of coverage of this appendix makes possible creation of appropriate and unambiguous abbreviations to fit almost every need. Botanical editors take note.

Appendix II, Political Chronology, deals with the vexing, frustrating, and often confusing matter of shifting

12

political alignments with corresponding name changes of countries and cities. Countries are listed first with a brief sketch of their history as applicable to botanical bibliographic considerations. The list of Geographical Name Equivalents will be greeted with enthusiasm by anyone who has ever struggled, sometimes without success, to trace a name overlooked in contemporary gazetteers and atlases. Thus, the uninitiated can learn that Bees, Bets, Vindobonum, and Wien are all names for Vienna or that Budapest, including subdivisions, may be referred to in literature as Alt-Ofen, Aquincum, Buda, Obuda, Ofen, Pest, or Pethini. This is a most useful adjunct which perhaps could be expanded in a future B-P-H edition although it serves its stated function well.

The majority of the text, pp. 25-1003, is the Periodical Listing with all periodicals listed in alphabetical order by the abbreviations. Every entry, whether a variant abbreviation or a full title with description, is numbered on each page. This numbering system is apparently a device for correcting errors and omissions which may occur in the computer printed text. This is not ordinary text, how-ever, as some 45 languages have to be accommodated, and a type train of 120 characters was specially designed for the print-out. Some minor details related to hyphenation and accent marks have been handled mechanically but in no way affect the high quality or usefulness of the text.

Everyone will not be fully satisfied with all recommended abbreviations as some are contrary to habit and a• bit unwieldy. It would seem that acceptable and unambiguous shorter abbreviations could be found for Aardappelstudiecentrum Kleinhandel, Bernice P. Bishop Mus. Bull., Occas. Pap. Bernice Pauahi Bishop Mus. (it is the same museum), Profess. Pap. Ser. Florida State Board Conservation Mar. Lab., or Verōff Forstl. Bundesversuchsanst. Mariabrunn Schonbrunn Abt. Standortserkund. Citation of periodicals with similar titles by including the place of origin or the editor is quite acceptable but why must parentheses be used so that the time-honored Bot. Mag. Tokyo becomes Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) ? Why is Bot. Mag. for Curtis's Botanical Magazine acceptable when one of the oldest American botanical journals is cited by the unwieldy Bot. Gaz. (Crawfordsville) just because three volumes of a Botanical Gazette were issued 1849-51 in Lon-don? It seems reasonable to let today's Bor. Gaz. be just that and distinguished from Bot. Gaz. London. A similar situation is found for Bot. Jahrb. Syst. (our familiar Bot. Jahrb.) because a single volume so obscure it is not in the Union List of Serials was produced in 1799 and listed as Bot. Jahrb. Jedermann. The several Journals of Botany have been dealt with in line with long usage and, save my personal distaste for the parentheses, are not objectionable.

The B-P-H has been put to considerable use for several months in my laboratory and the content has generally performed admirably. However, a troublesome, though I know not how frequent, problem did arise. The often cited Acta Soc. Bot. Poloniae is in the Union List only as Polski towarzystwo botaniczne. The handy little citation of 4-3391-3 in B-P-H leads one to the correct page and column where there is appended a note of the Latin name, but it would have been more convenient to have the Union

List name as well as its geographic coordinates when pre-paring literature search lists with only the B-P-H at hand.

Few errors have been detected so far but the entry under Rev. Bryol. Lichenol. seems to be incomplete and misleading. I have been unable to locate publications for "Annēe" 42, 43, 44, 45, or 46 (1915-1919). Husnot, the founder, had no part in the journal after 1926, Annēe 53, so Revue Bryologique effectively ceased to exist at that time. Pierre Allorge picked up the title and shifted publication to the Laboratoire de Cryptogamie, Paris, beginning the Nouvelle sērie with volume 1 with note of the 55`' annee on the masthead in 1928. With volume 5 (59e annee) in 1932, the title became Revue Bryologique et Lichenologique, and annual publication continued under that title through volume 11 dated 1938 and produced in 1939. The next issue, now considered volume 12, was is-sued with a 1941-1942 date as Melanges Bryologiques et Lichenologiques, a title which does not appear in B-P-H. The following four issues, now considered volumes 13, 14, and 15 (1 & 2), appeared 1942-1946 as Travaux Bryologiques, duly listed in the B-P-H but not described in the primary entry. With volume 16 (70e annee), 1947, the journal returned to its present title. This periodical continues to appear erratically and it seems to be better to cite volume numbers rather than the "annee" designations which are not always consecutive.

Despite such occasional minor differences with the editors about details, every botanist should luxuriate in the concise explanation of 413 entries beginning with the ever-troublesome Acta, or a variation, as the first word of the title or of the 229 entries under Izvestija. . . . In less than a year's use, the B-P-H has saved me dozens of man hours, as well as unknown quantities of adrenalin and aspirin, and has improved rapport with our willing, but chronically overworked, librarians. The fringe benefit of the ease by which new editions can be prepared by computer so that any current edition will be not more than five years old heralds a new era in bibliographic research. We can hope that such applications will spread as our literature becomes even more cumbersome and difficult to handle by conventional means.

The B-P-H is a big book having 11 x 8½ inch pages with narrow margins. It is substantially bound in a library-quality buckram with the fascicles sewn so that the book lays flat wherever opened. Quality of production is high as befits a book designed for heavy use. The price is moderate for these times and is well within the reach of plant scientists as well as many graduate students who should be introduced to it at the earliest opportunity. Botanists should note that continuation of the B-P-H depends upon widespread support by purchase and use of the book and by reporting difficulties, additions, and even disagreements to the editors. Such support is strongly encouraged.

A. C. Smith observed of the B-P-H in the Hawaiian Botanical Society Newsletter, "The botanical community, and all other individuals interested in any phase of plant life, may offer sincere congratulations to the editors and publishers of this compendium of unsurpassed value. It has a place in every library where scholarship is allied to an interest in the plant sciences." I could not agree more.

H. A. Miller